Category Archives: Public Theater

Elevator Repair Service’s ‘Ulysses’ by James Joyce, a Review

Elevator Repair Service became renowned when they presented Gatz, a verbatim six hour production of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby at the Public, as part of the Under the Radar Festival in 2006. Since their remarkable Gatz outing, they have followed up with other memorable presentations. It would appear they have outdone themselves with their prodigious effort in their New York City premiere of James Joyce’s opaque, complicated novel Ulysses. The near three-hour production directed by John Collins with co-direction and dramaturgy by Scott Shepherd, currently runs at The Public Theater until March 1, 2026.

At the top of the play Scott Shepherd introduces the play with smiling affability and grace. He directly addresses the audience, reminding them that “not much happens in Ulysses, apart from everything you can possibly imagine,” and that it happens in the span of a day beginning precisely at 8 a.m,, Thursday June 16, 1904 in Dublin, Ireland. Before Shepherd dons the character Buck Mulligan who appears at the beginning of the novel, he discusses that in the “spirit of confusion and controversy” (labels by critics), Joyce’s day in the life of three characters will be read with cuts in the text. Elevator Repair Service elected to remove Joyce’s text to redeem the time. The cuts are indicated by the cast “fast forwarding” over the narrative.

Collins and the creative team cleverly effect this “fast forwarding” with gyrating, shaking movement and action. Ben Williams’ design replicates the sound of a tape spinning forward. To anyone who may be following along with their own copy of the novel, the “fast forward” segments are humorous and telling. However, the cuts pare away some of the details and depths of character Joyce thought vital to include in his parallel of Dublin figures with the most important characters of the Odyssey: home returning hero Odysseus, long-suffering wife, Penelope, and warrior son, Telemachus.

After Shepherd’s introduction, Ulysses moves from a sedentary reading with multiple actors into a fully staged and costumed production as it progresses through the day’s events principally following Stephen Dedalus (Chisopher-Rashee Sevenson), who represents Telemachus, Leopold Bloom (Vin Knight), as Odysseus, and Molly Bloom (Maggie Hoffman) as Penelope.

The events illuminate these characters, and the cast superbly theatricalizes the novel’s humor, whimsy and farce. Some scenes more successfully realize Joyce’s playfulness and wit better than others. For example when Bloom decides to go to another pub after seeing the sloppy, gluttonous patrons of the first bar, the cast revels in portraying the slovenly, grotesque Dubliners. slobbering over their food. Additionally, the scene where Bloom faces his deepest anxieties shows Knight’s Bloom giving birth to “eight male yellow and white children.” Director Collins hysterically stages Bloom’s “labor” with Knight in the birthing position, legs apart, as Shepherd “catches” eight baby dolls he then throws to the attending cast members.

As costumes and props are added to the staging, we understand Leopold Bloom’s persecution as an outsider and a Jew. Also, wee note Stephen Dedalus as the writer/poet outsider who eventually joins Bloom, a father figure, who Bloom takes home for a time until Dedalus leaves to wander the night alone. Chistopher-Rashee Stevenson portrays the young Dedalus, a teacher whose unworthy friends lead him to drink and misdirection. Dedalus grieves his recently deceased mother and toward the end of the play has a nightmare visitation by her frightening, judgmental ghost.

For those familiar with the novel, the cast becomes outsized in rendering the various Dubliners that Knight’s Bloom and Stevenson’s Dedalus encounter. The dramatization is ultimately entertaining. We identify with Bloom as an Everyman, an anti-hero, who tries to get through the day in peace, while dismissing the knowledge that his wife Molly cuckolds him. Though he hasn’t been intimate with her since their baby Rudy died, he is unsettled that she conducts an affair with Blazes Boylan in their marriage bed at home. Somehow, Bloom has discovered that Molly who is a singer will be meeting with Boylan at 4 p.m. that afternoon. On his journey through the day he avoids confronting Boylan as they carry on with their activities around Dublin.

The ironic anti-parallel to the Odyssey, on the one hand, is that Molly Bloom is far from a Penelope who physically remained loyal to Odysseus, where Molly has an affair. On the other hand, late at night as Bloom sleeps with his feet awkwardly next to her face, we understand that Molly still loves Bloom and is emotionally and intellectually loyal. In her stream of consciousness monologue, seductively delivered by Maggie Hoffman, Molly arouses herself with memories of her relationship with Bloom when they were first together. It was then that she transferred a seed-cake from her mouth to his, sensually expressing her love.

Collins’s staging of the scene is humorous and profound. It defines why Molly has been present in Bloom’s consciousness throughout his strange journey traversing the streets of Dublin until he eventually finds his way home to her bed later that evening.

For those unfamiliar with Joyce’s novel, they will find the events and people a muddled hodgepodge that clarifies then becomes opaque, like a light switch turning on and off. Characters swap places with each other as seven actors take on numerous parts in a sometimes confusing array. Only Bloom, Dedalus and Molly stand out, true to Joyce’s vision for Ulysses for they embody Joyce’s themes about life. Thus, Bloom and Dedalus move through the day with flashes of brilliance, revelation, connection, irony and dread. Their reactions interest us. And Molly Bloom in her ending monologue puts a capstone on the vitality and beauty of a women’s perspective, as she experiences the sensuality and power of love for Bloom through reminiscence.

The costume design by Enver Chakartash reflects the time period with a fanciful modernist flourish that gives humor and depth to the personalities of the characters. For example Blazes Boylan (Scott Shepard) who has the affair with Molly wears a straw hat, outrageous wig and light suit that aligns with his jaunty gait. The scenic design by DOTS is minimalist and functional as is Marika Kent’s lighting design and Mathew Deinhart’s projection design. Most outstanding is Ben Williams’ acute, specific sound design which brings the scenes to life and follows the text adding fun and delight.

By the conclusion the audience is spent following the challenge of recognizing Joyce’s Dublin and the three unusual intellectuals and artists who he chooses to explore. Elevator Repair Service has elucidated the novel beyond what one might endeavor to understand reading it on one’s own. Importantly, they’ve made Ulysses an experience to marvel at and question.

Ulysses runs 2 hours 45 minutes with one intermission at the Public Theater through March 1, 2026. https://publictheater.org/productions/season/2526/ulysses

Caryl Churchill Strikes Again in a Provocative Suite of Metaphoric One-acts: Glass. Kill. What If If Only. Imp.

Glass. Kill. What If If Only. Imp.

Metaphor rides high in the four one-act offerings thematically threaded by British playwright Caryl Churchill. The suite is currently playing at The Public Theater until May 11th. Directed by James Macdonald, Churchill’s most recent collection integrates poetry, surrealism and “mundane reality” with a twist to represent the precariousness of our psyches in an incomprehensible world that populates the humorous and the horrible simultaneously.

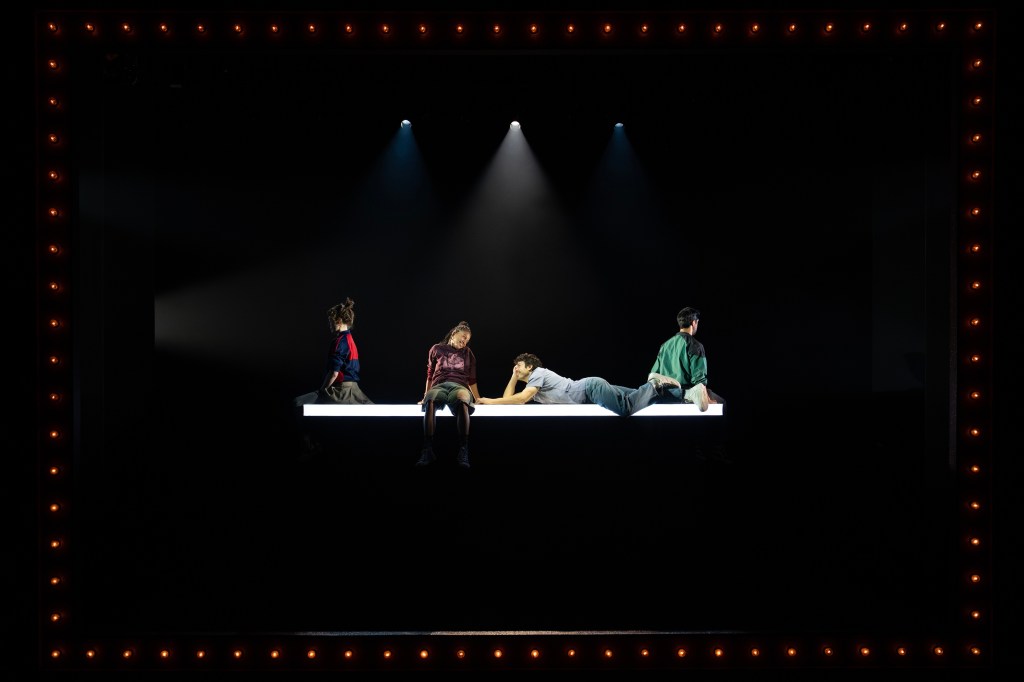

“GLASS” is a fairy-tale-like playlet that opens onto a lighted platform amidst darkness (scenic design by Miriam Buether), which we discover is a mantlepiece that holds objects. The protagonist is a girl of transparent glass (AyanaWorkman). According to the stage directions, “There should be no attempt to make the glass girl look as if she is made of glass. She looks like people look.” We meet her with others who are her jealous rivals, (an antique clock, a plastic red dog, a vase). Though the “glass girl” doesn’t seem to care to compete, the others humorously swipe at each other about who is the most useful, beautiful or valuable.

All look like people, suggesting a conceit. One interpretation might be that objectified humans come to believe in their own “grand” objectification. Other humans, aware of themselves, are transparently fragile, which can result in tragedy. Though Churchill’s meaning is opaque, the playwright adds layers. When Ayana Workman’s character is with schoolgirls, who persecute her and make her cry, her pain is visible both inside and out. Her vulnerability attracts a boy (Japhet Balaban), who becomes her friend and confidante. He whispers a story of his life with his father since he was seven. Though his whispers are not audible, we imagine the worst. Yet, we are shocked when the glass girl explains what happens to him which has a devastating impact on her.

The theme of fragility suggested in “GLASS,” is continued as an ironic reversal in “GODS,” after circus performer Junru Wang, presents stunning acrobatic maneuvers on handstand canes. The interlude with lyrical music provides time to reflect about aspects of life which require balance that only comes with training and practice as Junru Wang exhibits.

In “GODS,” Churchill casts the Gods of Greek and Roman mythology as the vulnerable ones. They unleashed the Furies to punish brutal humankind to no avail, then recalled them because humans never tire of bloodthirsty murders, wars, rampages. Deirdre O’Connell embodies all of the Gods. She sits suspended mid stage on a fluffy, white cloud surrounded by darkness, haranguing the audience in a stream of consciousness rant about the bloodletting, familial murders, intrigues, wars and cannibalism.

In a summary of bloody acts, O’Connell’s Gods admit they encouraged the brutality with curses and liked watching the results. But now in a humorous and ironic twist, they don’t like it. Furthermore, they wash their hands of the killing, because they don’t even exist. That is to say humans attribute their own monstrous behavior to the Gods instead of accepting responsibility for their own heinous acts. By the conclusion O’Connell’s Gods scream and plead, “He kills his son for the gods to eat and we say no don’t do that it’s enough we don’t like it now don’t do it we say stop please.” The Gods’ point is made. The audience agrees. The maniacal being, a human creation, haplessly protests its creators, knowing the bloodshed and murders will continue. If the gods had ultimate control would humanity be peaceable? Churchill’s irony is devastating.

Circus performer Maddox Morfit-Tighe creates the second interlude as he juggles with clubs and performs acrobatic movements. Macdonald positions both circus performers in the “pit” in front of proscenium using Isabella Byrd’s lighting design for dramatic effect. Churchill’s irony about humankind as performers who juggle and balance themselves in the tragicomical circle of life continues the thematic thread of vulnerability and fragility.

In “WHAT IF IF ONLY” a husband’s (Sathya Sridharan) grief over his wife’s death is so intense that his desire touches the spiritual realm, and the possibility of her return seems imminent when a “being” shows up. However, his suffering has evoked a ghost of “the dead future.” The being brings the horrific understanding that his wife is forever gone, subject to her vulnerable mortality. What is left are the illimitable future possibilities. But when the being suggests that he tries to make a possibility happen, he claims he doesn’t know how. His grief has cut off his ability to even conceive of a future without his wife.

No matter, a child of the future (Ruby Blaut), shows up. Though he ignores the child, she affirms she is going to happen. As we daily ignore our vulnerable, mortal flesh to live, the future will happen, until we die. Churchill frames life as hope with possibility that we must let happen.

After the intermission Macdonald presents Churchill’s uncharacteristic, humorously domestic one-act “IMP.” The last play continues the thematic threads but buries them in the ordinary and humorous. The significance of the title manifests well into the play development after we learn the back story of two cousins who live together, Dot (O’Connell), and Jimmy (John Ellison Conlee), and their two visitors, niece Niamh (Adelind Horan), from Ireland, and local homeless man Rob (Japhet Balaban). During Rob’s visit with Jimmy, since Rob doesn’t want to discuss any personal details about himself or the possibility of a relationship forming between himself and Niamh, Jimmy decides to share a family secret. Dot believes she captured an imp that is in a wine bottle capped with a cork.

Though Jimmy claims not to believe the imp exists, at Bob’s suggestion, he uncorks the bottle. In the next six scenes we watch to see if anything changes in the lives of these individuals and are especially appalled when Dot wishes evil on Rob via the imp when she discovers that Niamh and Rob split up. We discover the imp’s power by the conclusion. However, the act of Dot’s powerlessness and vulnerability in projecting her own malevolent wishes through a mythic creation to avenge a loved one is pure Churchill. This is especially so because in this homely environment where nothing unusual happens, there is the understanding that people activate myths. Indeed, our beliefs may comfort, but on another level may entrap and even destroy.

Glass. Kill. What If If Only. Imp.

Running time is 2 hours15 minutes with one intermission, through May 11th at the Public Theater publictheater.org.

‘Sally & Tom,’ Suzan-Lori Parks’ Brilliant Play About Hemings and Jefferson, a Must-see

That “all humankind is created equal,” never was penned by Thomas Jefferson, nor by our most illustrious founding founders, who insured that only privileged white men with property were “equal” enough to vote. This is well noted by Suzan-Lori Parks in her satiric, New York premiere Sally & Tom, directed by Steve H. Broadnax III, currently running at the Public in its fourth extension until June 2nd.

Suzan-Lori Parks (2002 Pulitzer Prize and 2023 Tony Award winner for Best Revival of a Play for Topdog/Underdog), takes up Thomas Jefferson and fillets him for a farcical repast in this exceptional, complex new work. Examining Jefferson’s relationship with his slave mistress Sally Hemings (with whom he fathered six known children), Parks uses “their love” as fodder for her satiric cannons. She employs a play within a play structure to heighten the complexities of shedding noxious, historical, cultural notions and facing the contradictions in human behavior when attempting to do so.

During the process, where she alternates scenes from the play Pursuit of Happiness set in the past, and the actors working backstage to rehearse, revise and reconfigure the play in the present, Parks elucidates themes about racism, slavery, the patriarchy and power domination. Gradually, she reveals how the actors, and three of the technical team realize that these elements permeate their cultural attitudes in their own lives, despite their assumptions that they’ve released themselves from such bondage. Parks’ intention is for us to identify with the Good Company’s enlightenment and self-awareness toward a new “freedom.” Finally, Parks uses the occasion to expose fascinating information about “Sally and Tom” that the audience may not have known before.

Taking cues from Parks’ dialogue, Broadnax III’s setting leaps seamlessly as it alternates back and forth from 1790, Monticello, Jefferson’s plush home where the play, Pursuit of Happiness predominately takes place. Then Sally & Tom shifts to the present, backstage, and in the apartment of actors and lovers, Mike, the director, who plays Jefferson (Gabriel Ebert), and Luce, the playwright, who plays Sally (Sheria Irving). Like the characters they portray, Mike and Luce are intimate partners in their lives. Like Sally Hemings, Luce discovers she’s pregnant during the course of reworking and acting her role in the Pursuit of Happiness.

As a humorous, Mark Twain-like ironist, Suzan-Lori Parks sends up the cliche that truth in life is stranger than fiction, as the parallels between Sally and Tom and Mike and Luce blow up by the conclusion.

Broadnax III’s technical team crafts the sets (Riccardo Hernandez), costumes (Rodrigo Munoz), hair, wig, and make-up (J. Jared Janas & Cassie Williams), lighting (Alan C. Edwards), sound (Dan Moses Schreier), and music (composers-Parks and Dan Moses Schreier), to clarify when and where the action is unfolding. As the actors wrangle with increasingly desperate and funny problems, putting on the performance about Jefferson and Hemings, all of the characters/actors have different goals in their own pursuits of happiness. We get to see some of them blossom and others implode.

The enjoyment of Parks’ delightfully meaningful work is that one becomes immersed in both the Monticello past and the backstage present. The illusion of Jefferson’s Montocello is recreated at the top of the play as Tom and Sally dance the minuet accompanied on the violin by the slave, Nathan-actor counterpart Devon (Leland Fowler), as guests regaled in period clothes and wigs, enjoy their turns around the dance floor. As Parks exposes the colonial, repressive, anti-democratic culture of that time and stands it on its head in Pursuit of Happiness, she twits the current politically skewed theater trends presenting upbeat, nonthreatening productions, which offer “talk backs” when subjects skirt the edges of “triggering,” in order to “work through” potentially offended audience sensibilities.

Indeed, the actors of Good Company have changed their attitude toward offending audiences in this latest play to “stay alive,” and keep their company solvent. Good Company has been stretched to its limits in the past because audiences have rejected their “in-your-face” productions like “Listen Up, Whitey, Cause It’s All Your Fault.” Their producer and key financier Teddy schmoozes Luce and Mike to keep Pursuit of Happiness palatable to a diverse crowd.

The play is heavy on accurate information. Jefferson’s “kindness” to his slaves is suggested up to a point. However, one senses the irony of a sub rosa rebellion underneath this essentially Black play which points up the scandalous “relationship” of the “good guy” Jefferson and presentation of Sally, Jefferson’s mistress, who gently gestures to her baby bump at the end of the play. Theirs was no love relationship, Luce, the playwright insists.

As the playwright Luce and director Mike rework various scenes, put in and take out inflammatory speeches, and try the patience of their producer, who eventually quits because the play is still too “in your face,” they evolve in their understanding. They are forced to modulate their impulses which reflect the present.

Some of the actors, prefer to show that the oppressed slaves had agency. In one instance, a beautiful speech is so incendiary, Teddy wants it to be removed because then, the play would be a hit and “sell,” and he’d get his money back, obviously. The point is made that during Jefferson’s time, a slave’s agency would be construed as an act of rebellion and punished with death.

The tension between what was (the oppressive horrors of slavery), and what is (current cultural freedom especially in New York City), rocks Kwame (Alano Miller), who is on the verge of “making it” in the business. Kwame portrays Sally’s brother James, who Jefferson promised to free when they returned from Paris, where James enjoyed freedom as the other Blacks did. However, when Jefferson et. al. return to Virginia where slavery is the law of the land, Jefferson makes excuses about freeing James, because why would he do what is illegal and frowned upon by the society of his plantation peers?

James continually confronts Jefferson about his promised freedom, and stands up to Colonel Carey portrayed by Geoff (Daniel Petzold), who refers to Sally, his sister, as a “fine animal.” When Jefferson “mildly” rebuffs James telling him to “remember himself,” James holds forth in a three minute speech which producer Teddy insists must be cut.

As brother James, Kwame enjoys speaking truth to power, though it is completely ridiculous for the 1790s South. It is clear that Kwame chafes at portraying a slave and feels he must redeem himself in such a role. The speech, which he delivers to “perfection” is his shining moment. The cast initially agrees and Luce, believing that Teddy is under her power, massages the producer to keep the speech and prevent Kwame from walking. Instead, Teddy quits and Mike and Luce are left with a financial abyss to fill and a long speech which makes no sense in Jefferson and the fledgling United States’ tide of times. Of course the “full of himself” Kwame believes his empowerment speech is the only value Pursuit of Happiness has.

The show, however, does go on as Mike and Luce’s relationship is sacrificed, Kwame quits, scenes are rewritten at the last minute and the acting “troopers” pull together and get to opening night. In the process, the farce unleashes and the admixture of revelation and forgiveness but not forgetfulness wins the day for the actors, and even for Sally and Tom at the “perfect” conclusion, that a sadder but wiser Luce has written for Pursuit of Happiness.

The actors are top notch in this glorious ensemble where Sun Mee Chomet, Kristolyn Lloyd and Kate Nowlin portray supporting roles. For those who gloried in founding father Thomas Jefferson’s iconic stature, Parks, speaking through Luce, pointedly suggests Sally did not love Tom. Though he supposedly was a kind master, unless one could go back in a time machine taking one’s present-day perceptions with them, it is impossible to know, given he kept 600 slaves and sold them off to raise money when he went to the Capitol, New York City. Finally, the audience is reminded that our great founding father never gave Sally her freedom. It was Jefferson’s daughter Patsy, disappointed at her father’s lascivious behavior, who finally freed Sally after Jefferson died.

If the Good Company had had their way with Teddy, who most probably insisted they change it, the title would have been E Pluribus Unum (“out of many, one”), instead of the benign Pursuit of Happiness. One would think that the implied unity has yet to be achieved in our nation, culturally fractured by foreign adversaries like Putin for politically opportunistic reasons. However, looking beyond social media posts of Marjorie Taylor Green, MAGAS, and Russian and Chinese trolls, federally, we are indeed, E Pluribus Unum, united and standing tall, while we attempt to iron out issues, as Parks points out, that are extremely complex.

Sally & Tom runs two hours, thirty-five minutes with one intermission at The Public Theater, on Lafayette Street. I loved it.

‘Manahatta,’ Another View of The Lenape at the Public

In Manahatta, written by Mary Kathryn Nagle and directed by Laurie Woolery, the myth of how Manhattan was purchased from the Lenape, and how the exploitation of Indigenous Peoples continues today, conjoins in a powerful message. Nagle’s play, currently at the Public, is more symbolically realized than factual. The playwright admits that the work, though based on true events, is a work of fiction. Nagle researched and conducted interviews with the Lenape and those of the Delaware Nation. What resulted, after workshopping, and full presentations at Oregon Shakespeare Festival and Yale Rep, is an enlightened work whose themes weave from past to present, reflecting issues of our time.

The play opens with Jane (Elizabeth Frances), being interviewed by Joe (Joe Tapper), who would be her boss at an investment bank in the heart of Wall Street. The investment bank is less than a mile from Pearl Street, named for the huge mound of shells the Lenape left after they had been forcefully expelled from their Northeastern homelands to eventually end up in Oklahoma. Jane, a Lenape, who excelled in financial math and was number one in her class at MIT and Stanford, is hired after she reveals to her boss that interviewing for the job was more important than staying with her family, while her dad received open heart surgery.

Jane tells Joe that she didn’t go to Stanford because her parents, who never graduated from high school told her to, like the other privileged, bored, uninterested students she competed against. She went there because she “knocked down every obstacle they placed in my way.”

Clearly, Jane is determined, intelligent and the first Indigenous Person hired on Wall Street to return to a place of great symbolism, the home from which her tribe originated. When she returns to Oklahoma, she returns to her father’s funeral, and her sister Debra’s (Rainbow Dickerson) recriminations that she left her family and her tribe for a life in the concrete jungle, “without trees or a sky.” Her mother, Bobbie (Sheila Tousey is terrific as the stoic, ironic matriarch), asks her to find the wampum necklace she will wear at the funeral, a Lenape ritual, which Debra eventually finds because Jane is clueless, not having lived with Bobbie for years.

Significantly, the wampum has been carried down from generations of ancestors and is the most valuable treasure Bobbie owns. Nagle uses the wampum as a symbol of the strength, perseverance and inner fortitude of the Lenape, that abides throughout time, disasters and oppressions by others.

After the funeral, Bobbie engages in a conversation with Michael (Rex Young the evening I saw it), the pastor of the church where Bobbie’s husband sang in the choir. During her conversation with Michael, Bobbie discusses that the Indian Health Service, a government agency responsible for providing health services to Native peoples, refused to pay for the open heart surgery. Bobbie elicits Michael’s help as a loan officer to take out a mortgage on her house to pay for the hospital bills. Not wanting to tell her daughters, she works with Michael and his son Luke (Enrico Nassi), who understands the problem and eventually Michael provides the loan at a high interest rate so she can pay off the hospital bills.

Using seven actors to double on their counterpart roles, Nagle creates a parallel plot point. The setting reverts to 17th-century Manahatta. Se-ket-tu-may-qua (Enrico Nassi), and a Lenape woman, Le-le-wa’-you (Elizabeth Frances), prepare beaver pelts for the Dutch West India Company traders with whom they make trades for wampum. Se-ket-tu-may-qua warns Le-le-wa’-you that she shouldn’t go to the market, even though she wishes to learn the language the Dutch speak. He tells her that he has seen cruel behaviors the men do to Lenape women and suggests they are dangerous. When Peter Minuit (Jeffrey King), realizes the value of the beaver pelts to Amsterdam, he greedily makes deals with Se-ket-tu-may-qua and Le-le-wa’-you for more and more pelts.

Jane’s story unfolds on Wall Street as she begins to realize the mortgage backed securities her team is selling aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on. Though she questions their value, company CEO Dick (Jeffrey King), validates their ratings and justifies the company’s rising stock prices. He also suggests that unless she becomes a real team player, closing many more deals, he will fire her. Jane pulls out a coup, though she must lie to do it. She saves her job, even getting a promotion. Parallel to this action, Bobbie is not making the payments on her mortgage, which ironically is like one of the bad mortgages bundled up into credit default swaps that are worthless, yet are being sold by the Jane’s company and Jane’s team as a great investment.

In the parallel with the past where the notion of money and commercialism was planted like diseased corn in the fields of the Indigenous Peoples to infect their good crops, Peter Minuit (over an alcoholic beverage he shares), strikes a deal with the Lenape and Mother (Sheila Tousey), for the land of Manahatta. Mother, not understanding the concept of ownership of land “in perpetuity,” ends up “selling” Manahatta to Minuit for wampum. This is interpreted as being a gift, making Minuit a part of their family and vice versa. That they are now family members is an incredible irony, for the Dutch with bad will interpret it to mean they have the license to destroy “their Native kin” through assimilation and/or murder if they resist.

With this purchase, Nagle presents the unfortunate fact that the Dutch have insinuated their corrupt and rapacious values into the Lenape culture, eventually overcoming it. Meanwhile, Lenape culture doesn’t have in it such a conceptualization of possession of land, animals, etc. but instead has a view of balance and propriety. Such corrupt transactions symbolically are at the heart of the abuse and recklessness that colonial empires have wielded on Native peoples and the flora and fauna of their lands that they eventually steal outright. The disdainful theft of lands in empire building is a destructive, wicked force that has led to erecting questionable societies that are life defying and earth destroying. Sometimes, little thought is given to the consequences of such tearing down and building.

It is no small irony that the derelict disregard and wastefulness that rapacious possession has perpetrated has as its end game climate change, pollution, and destruction of the very environment possessors and oppressors would call “home.”

After the sale, the Dutch take greater and greater control over the identities and self-determination of the Lenape. They attempt to spread Christianity, demand the Lenape pay a tax to sell the beaver pelts on “Dutch land,” and only pay guilders for the pelts. In this, the playwright foreshadows the downward spiral toward full on oppression and death, as the colonials attempt to wipe out their “sin” by eradicating the cultures of the Native peoples in an explosion of barbarism, greed, corruption and genocide. As Nagle moves the action from Bobbie to the Dutch to Jane we note how the present is mirrored in the past.

In the remaining parallel segments, we see the ill effects of the mortgage debacle visited on Bobbie and others like her, who can’t keep up with the mortgage payments and must default. When Jane offers to pay off her mother’s mortgage, Bobbie refuses the money, standing on her pride and her ancestry. In a heartfelt, beautifully delivered speech Tousey’s Bobbie affirms to her two daughters that material things are worthless, and that she relies on the resilience and strength of her ancestors to withstand any hardships put before them. In keeping the ancestral wampum, she has been sustained and grounded in the true value of life and the sanctity of her culture.

Ironically, this spiritual grounding is something the Dutch and all empire builders do not have and will never understand, appreciate, nor pursue. Ultimately, this blindness works like karma and turns empire builders against themselves so that they ultimately destroy their own empires.

Nagle reflects this truism in the circumstances with Jane. Ironically, Jane who has earned a bonus of $1 million dollars for making an incredible sale, is the only one in the company who actually moves to a better position, while Dick (Dick Fuld of Lehman Brothers), cannot stop the short selling against the firm whose stock price crashes so Lehman goes belly up. Jane, who foresaw what might happen and tried to warn her bosses, learns that the bad faith represented by the credit default swaps of subprime mortgages has created a global financial debacle. However, Dick tells Jane she is in great shape and will be recruited while his career is over, and he will most likely be sued.

At the conclusion Jane affirms her identity as a Lenape, who has returned home to Manahatta, victorious, overcoming the conquerors with the hope that perhaps she can change things. Meanwhile, her mother and sister have joined the homeless populations, and with their few possessions they will carry on and survive, despite the horrific circumstances the blind, derelict empire builders have created.

Nagles’ Manahatta builds toward a satisfying and poignant conclusion because of the efforts of the director and the fine ensemble. As she embodies the past in the present, we recognize the ironic reversal of karmic fortune. Jane triumphs as a woman and Lenape, after besting the colonials at their own game. That she hopes to bring change is questionable. Meanwhile, Bobbie’s values are eternal and overcoming. It is her story that is one of honor and greatness. It suggests immutable truths that affirm the inevitable destruction of empires and those who build them, devoured by their own evil.

The ensemble works seamlessly together and the tension builds so that Nagle’s themes about virtue, honor and the immutability of innocence and goodness are unmistakable against a backdrop of the oppressions of greed that destroy those who allow it to overtake them. Indeed, Nagle affirms the truism that the love of money is the root of all evil.

Kudos to the creative team that help to bring together the director’s vision for this sterling production. Manahatta is at the Public Theater on Lafayette Street downtown. https://publictheater.org/productions/season/2324/manahatta/

‘Hamlet,’ Kenny Leon’s Dynamite Version, Free Shakespeare in the Park

There are more iterations of Hamlet presented globally in the last fifty years than are “dreamt of in your philosophy.” To that point director Kenny Leon’s version of Hamlet, currently at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park until August 6th, provides an intriguing update of the son for whom time is so “out of joint,” he is unable to seamlessly and speedily avenge his father’s murder. Leon’s version shapes a familial revenge tragedy. Once set on its course, dire events cannot be averted, for at the core is the initial corruption, “the primal eldest curse, a brother’s murder” that “smells to heaven.” From that there is no turning, until justice is served, the sooner the better.

In this 61st offering of Free Shakespeare in the Park, we immediately note the conceit of corruption and its ill effects to skew the right order of things, making them “out of joint,” off-kilter. This is an important theme of the play (expressed by Hamlet) and represented by Beowulf Boritt’s set, some of which is a wrecked-out remnant of his design from Leon’s pre-Covid production of Shakespeare’s comedy, Much Ado About Nothing.

That 2019 design sported a resplendent, brick, Georgian mansion that stylistically conveyed the wealth and rectitude of its Black, lordly owners rising up in a progressive South. Hope was represented by a “Stacy Abrams for President” campaign sign proudly displayed on the side of the building. A towering flagpole and American flag patriotically stood like a sentinel at the ready. Peace and order reigned.

It is not necessary to have seen Much Ado About Nothing to understand the ruination and disorder foreshadowed by Boritt’s Hamlet set which coherently synthesizes Leon’s themes for his modernized version. In one section a tilted smaller version of the former Georgian house appears to be sinking off its foundation. On stage left, an SUV is tilted off center, undrivable, in a ditch. The Stacy Abrams’ sign is torn and displaced on the ground like discarded trash. And the American flag with its long flagpole angled toward the ground signals distress and a “cry for help.”

The only ordered structure is the cutaway of a building center stage (used for projections), whose door the characters enter and exit from.

Boritt’s set design suggests “something is rotten” unstable and “out of joint” in this kingdom. Themes of devolution are foreshadowed. From unrectified corruption comes disorder which breeds chaos and dark energy, out of which destruction and death follow. And all of this springs from the unjust murder of the deceased in the coffin that is draped in an American flag and placed center stage. It is his life which is celebrated by the beautiful singing of praise hymns at his well-attended funeral in the prologue of Leon’s Hamlet. It is his life that is memorialized by the huge portrait of the kingly father in military dress which hangs watchful, presiding over events from its position on the back wall of the only part of the set that is not wrecked and disarrayed.

Cutting Act I scene i (soldiers stand on guard watchful of an attack from Norway), Leon opens with the elder Hamlet’s funeral. A Praise Team joined by a Wedding Singer, who we later recognize to be Ophelia (the golden-voiced Solea Pfeiffer), sing with beautiful harmony. Jason Michael Webb created the music and additional lyrics which set out the Godly tenets that all are importuned to follow or live by. To their downfall they don’t and this is manifested in tragedy.

Importantly, the first three songs are taken from the Bible. The first is from Ecclesiastes (“To everything there is a season). Then follow Matthew 5 (“To show the world your love, I’m goona let it shine”) and I John 5 (“When you go on that journey you go alone”). The last song that Ophelia sings is composed of lines from a love poem that Hamlet wrote for her.

The songs intimate the former moral rectitude and divine unctions found in the former Hamlet’s kingdom. Ironically, the memorial service represents the last peace that this kingdom will appreciate. As the set indicates, wrack and ruin have already begun. The scenes after the funeral represent declension and growing darkness. And after old Hamlet is buried, nothing good follows.

Numerous cuts (scenes, lines, characters) abound in Leon’s version. His iteration presents questions about the disastrous consequences of familial revenge which is different from Godly justice suggested by the songs. Importantly, Leon’s update (sans scene i) gets to the crux of the conflict with scene ii, the marriage celebration of Claudius (the terrific John Douglas Thompson and Gertrude (Lorraine Toussaint is every inch Thompson’s equal). We note their public affection for one another, which Hamlet later intimates is a lust-filled marriage in an “unseemly bed.” The partying has followed fast upon the old Hamlet’s burial, to the dismay and depression of his loyal son.

It is during the festivities when the sinister intent of the new king and duped mother Gertrude chide Hamlet (the fabulous Ato Blankson-Wood). They suggest he put off his mourning clothes, “unmanly grief” and depression for it is “unnatural.” Already, the cover-up has begun and Hamlet is the one individual Claudius must be circumspect about as the rightful heir to a throne which he usurped.

Gertrude importunes Hamlet to remain in the kingdom instead of returning to his studies in Wittenberg, and dutifully, he obeys, stuck with the daily reminder of his father’s death and mother’s “o’er hasty marriage.” This version emphasizes Claudius’ sincerity covering over his suspicion and fear of Hamlet. He is happy to keep him under his watchful eye. Throughout his magnificent portrayal, Thompson’s Claudius gradually reveals his underlying guilt and fear for his crimes of regicide and fratricide. We see his behavior grow more and more paranoid about Hamlet as the conflict between them grows and Hamlet unloads snide remarks on Claudius, Polonius and all those who are obedient to the usurper king as a provocation.

Leon’s version is a familial revenge tragedy which eliminates any reference to Norway or Prince Fortinbras seeking justice for his father’s death in battle with Denmark. Leon is unconcerned with Norway and Fortinbras. The conflict in his Hamlet is internal to Denmark, a divided kingdom like “an unweeded garden, rank and gross in nature.” Divided against itself, with brother vs. brother and son vs. uncle, and Gertrude the exploited, seduced pawn, Claudius’ guilt is a canker worm which gnaws at him. Likewise, gnawing at Hamlet after his father’s ghost’s visit, is the knowledge of what has to be done. But he maintains, “cursed spite, that ever I was born to set it right.”

All is covert and the truth is covered up. Polonius and Claudius spy on Hamlet to divine why he is “mad,” and Hamlet acts mad and rejects Ophelia’s love during the process of divining whether the ghost is telling the truth. Intrigue, chaos and darkness augment and have their way with the innocent and guilty. For Hamlet, the “time is out of joint.” An intellect, he is “blunted” (the ghost later says) from making the correct decisions or acting upon them in a timely fashion. The darkness that Claudius has set loose taints Hamlet and every principal character that must show obeisance to King Claudius’ illegal reign.

Key to the argument of choosing vengeance vs. justice is the enthralling scene when Hamlet meets his father’s ghost. Initially, the creative team (Jeff Sugg’s projections, Allen Lee Hughes’ lighting design, Justin Ellington’s sound design) present the father’s ghost on the back wall with projections on the portrait and the wall, accompanied by the ghost’s booming, shattering voice, which commands Hamlet’s obedience.

But at the description of the murder, the ghost possesses Hamlet. Blankson-Wood’s performance of the ghost consuming his soul is phenomenal and physical. He arches his back with the jolt of spirit possession and then rights his gyrating body as his father’s voice spews wildly from him, eyes rolled back, arms waving, the very picture of the demonic that Horatio (the fine Warner Miller) warned Hamlet might “tempt him to the flood.” At once frightening and mesmerizing, the possession enthralls us and changes Hamlet. It is a dynamic, successful scene showing the decline in the goodness from the initial praise songs to the devolution of the spirit’s will demanding vengeance. We are thunderstruck. Blankson-Wood’s authenticity frightfully convinces us of the spirit’s potential for evil misdirection into a vengeance which is not just and will bring devastation.

After the ghost leaves the vessel it inhabited and Hamlet swears Horatio and Marcellus (Lance Alexander Smith) to secrecy, Hamlet’s fate is sealed. He moves toward faith in the ghost, farther away from the light-filled unctions in the songs at his father’s funeral. Now, there is no “showing love” and “shining one’s light.” Intrigue and acting “mad” and conspiracy and cover-up overtake the mission of the kingdom. Hamlet toys with and ridicules Polonius (Daniel Pearce gives a humorous, organically funny portrayal) and does the same with Ophelia in a powerful scene, eschewing his love for her. Pfeiffer’s Ophelia shows her devastation and shock. His behavior is a complicating truth for everyone and it intensifies Hamlet’s conflict with Claudius.

Knowing Hamlet’s madness is not for Ophelia’s love, Claudius grows more paranoid and guilt laden. Clearly, when the actors make their presentation of the dumb show (Jason Michael Webb’s song “Cold World” is superb), and Hamlet presents ‘The Murder of Gonzago,’ he and Horatio see that Claudius’ guilty conscience is made manifest in ire and defensiveness. Though this scene is truncated, as is Hamlet’s description of how the actors should proclaim their speeches, no coherence is lost. Claudius runs away, his soul uncovered. Hamlet is convinced vengeance is the right course of action. But he has allowed himself to be misguided. Nothing good will come of following the ghost’s lead.

Leon truncates the minor speeches, retaining those that convey Hamlet’s angst at being stuck in the kingdom which is a prison. He can’t commit suicide (“To Be or Not to Be”) because his morality and fear of death forbids it. Stuck in Denmark, everyone is a potential enemy except Horatio. He uses coded speech with everyone especially Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, who Claudius/Gertrude have engaged to spy on him. Ato Blankson-Wood delivers the key soliloquies powerfully with insight as he makes the audience his empathetic confidante who understands his intellect has chained him to inaction. We are drawn into his plight, but become frustrated when his determination falters.

The paramount event where his intellect intrudes happens when Claudius is praying in the church (fine stylized staging). Coming upon Claudius, Hamlet rejects the opportunity to kill him because he thinks Claudius is confessing his sins and getting right with God. However, it is a missed opportunity which Hamlet squanders because Claudius’ prayers fail (“my words fly up, my thoughts remain below; words without thoughts never to heaven go.”). Claudius realizes to receive forgiveness he would have to give up the throne, Queen and his cover-up which he will never do.

Hamlet lacks proper discernment and moves from his bad decision to impulse. Not killing Claudius in the church, he rashly and mistakenly kills Polonius, assuming incorrectly that Claudius quickly ran up to Gertrude’s room. The stakes are raised for Claudius and Hamlet. Polonius’s death missing body incense Claudius who is overwrought with fear knowing his enemy Hamlet has put a target on his back.

Once more, the “time is out of joint,” and Hamlet defers vengeance and subjects himself to Claudius, finally revealing where Polonius’ body is. For Gertrude’s sake, Claudius sends Hamlet away with the orders for others to kill him in a plan that fatefully backfires.

Leon’s version has clarified the stakes for Claudius to escape accountability, manipulating Laertes (Nick Rehberger) from killing him by blaming Hamlet. Thompson conveys each of these cover-ups with precision. Also, clarified is Blankson-Wood’s angst and struggle confronting his father’s murderer. His use of irony as a weapon to prick Claudius’ conscience is superbly rendered as are his soliloquies whose philosophical constructs tie him in emotional knots. Hamlet, knowing that he is stuck in a morass with no way out, recognizes that like the other characters, he is on a collision course with destiny and ruination which is foreshadowed at the beginning with Boritt’s set.

Also, clarified in this version is Toussaint’s Gertrude who is in a state of ambivalence and guilt stirred by Hamlet’s antic behavior, which she suspects is his response to her marrying Claudius. When their confrontation occurs after Hamlet kills Polonius, she knows her relationship with Claudius must be thrown over, yet she hesitates and discusses Hamlet with Claudius ignoring Hamlet’s wise counsel. The doom she recognizes in Ophelia’s madness will only bring more sorrows, a trend which both Claudius and Gertrude comment upon. Toussaint’s description of Ophelia’s drowning is heartfelt and mournful.

The flow of events coheres because the through-line of Claudius and Gertrude in conflict with Hamlet is maintained with intensity. Stripping Norway from the action and leaving Fortinbras out of the conclusion is to the purpose of Leon’s emphasis of the familial tragedy. The contrast of the good son and man of action who achieves justice (Fortinbras) with Hamlet’s flawed son of inaction who is Fortune’s fool, exacerbating destruction via revenge gone wrong would have pleased Queen Elizabeth I. Contrasting the two Prince’s and showing the heroic one in Fortinbras is an encouragement of how royalty should rule. However, it doesn’t fit with the themes that Leon emphasizes, especially that a “house divided against itself cannot stand.”

Hamlet concludes with the slaughter of two families tainted by their association with a corrupted king, out from which there is no release except death. A final theme current for our time suggests that unless individuals stand against usurpers of power, the usurper and all who are his accomplices by not bringing him to justice will pay the forfeit of their lives and fortunes.

However, only Miller’s Horatio understands the full story of Hamlet and the striving between vengeance and justice. That vengeance brings disaster is why the ensemble finishes with the actors’ song that they sang when Hamlet first meets them. It is poignant and true and heartfelt when the spirit of Ophelia joins them and together they sing, “I could tell you a tale, God’s cry. It could make the God’s cry.”

Kudos to the ensemble and the creative team who carry Leon’s vision of Hamlet into triumph. These include those not already mentioned: Jessica Jahn’s colorful costume design, Earon Chew Nealey’s hair, wig and makeup design, Camille A. Brown’s choreography and Gabriel Bennett for Charcoalblue and Arielle Edwards for Delacorte’s sound system design.

For tickets to this unique Hamlet which has one intermission, go to their website https://publictheater.org/productions/season/2223/fsitp/hamlet/

‘Raisin in the Sun,’ a Glorious, Triumphant Revival at the Public

Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry, aptly titled referencing the Langston Hughes’ poem, “A Dream Deferred,” is enjoying its fourth major New York City revival. It debuted on Broadway to great acclaim in 1959 and followed with two other Broadway showings in 2004 and in 2014 with Denzel Washington. Now at the Public Theater extended again until November 20th, director Robert O’Hara and the cast, led by Tonya Pinkins, prove that Raisin in the Sun is an immutable masterpiece. Its themes of discrimination, injustice, greed, family unity and love encompass all human experience.

The heartfelt, moving, vibrant and electric production, which lives from moment to moment in joy, humor, sorrow, fury, wisdom and dignity, incisively honors Hansberry’s work in its showcase of Black Americans in this triumphant production. However, more than other revivals of Raisin in the Sun, this cast, creative team and director convert Hansberry’s work to the realm of timelessness. The production is an inspiration, an event of humanity which is incredibly relatable to all races, creeds and colors.

In its particularity the play is about the seminal Black experience in America during a shifting, revolutionary time of great economic and human rights change for African Americans in the 1950s. However, Hansberry’s thematic vision stretches beyond the microcosm. This magnificent play encapsulates the macrocosm with Hansberry’s genius characterizations, conflicts and themes in transcendent writing. For at its heart the play is universal in revealing the human desire to achieve, to evolve, to be empowered, to give voice to one’s soul cries for recognition, for equity, for prosperity.

Made into two films, a musical, radio plays, a TV film and inspiring a cycle of three plays (Raisin in the Sun, Clybourne Park and Beneatha’s Place), Hansberry’s work is a classic not to be taken on lightly. However, Robert O’Hara, the cast and the creative team understand the great moment of Hansberry’s work for us today. With their incredible production at the Public, which opened October 25th, they have elucidated the heartbreak, fury, joy and beauty of Black experience as they portray how the Younger family struggles to find their place in a culture of racial oppression, stupidity and cruelty.

O’Hara’s version has additions which enhance the symbolism of Hansberry’s themes. Walter Lee Sr.’s presence materializes as a ghost (Calvin Dutton), who inhabits Lena’s thoughts and remembrances. His unobtrusive presence symbolizes Lena’s heart and love for their family. The insurance check represents the sum total of how the world credits Walter Lee Sr.’s life, an irony because for Lena, no amount of money is an equivalent to the worth of her husband. In fact the insurance check that rattles the household and puts stars in the eyes of Walter Lee Jr. (the amazing Francois Battiste), is blood money to Lena, a blasphemy that she doesn’t want to even touch when the mailman delivers it and she has Travis (Toussant Battiste), read off the number of zeros.

O’Hara’s staging is unique and vital, adding nuance and clarity to Hansberry’s dialogue and characterizations. Mindful of the play’s high-points, he stages the characters priming our focus to receive the full benefit of Hansberry’s message. This is especially so for Walter Lee’s inflammatory and raging monologue about “the takers and the taken,” in previous productions delivered to Lena, Beneatha (Paige Gilbert) and Ruth (Mandi Masden). In O’Hara’s version, Battiste’s Walter Lee stands in a spotlight and delivers the speech to the audience. It is mindblowing, reverential, brilliant, confrontational. More about this staging later.

The performances are authentic and spot-on fabulous. O’Hara’s direction is so pointed and “in-your-face,” the audience is invited to stand in the shoes of the Younger family, watching their trials with empathy. We feel for Masden’s Ruth when Lena confronts her about putting money down for an abortion. Her sobs of desperation at being driven to this because they can’t afford a child recall the past and now Republican states in the present. Considering the impact of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, as a throwback to Ruth Younger’s seeking an illegal abortion, this moment in the play breaks one’s heart. Masden inhabits the character with somber beauty and layered emotion. When she must pull out the stops, sobbing her hopeless despair to Lena, she is spot-on believable.

Likewise, as Gilbert’s Beneatha decides between two men and carps and riffs on brother Walter Lee, we understand she is caught between the old and the new. She represents transformation and is on the cusp of the new feminism. Accepting African influences prompted by her relationship with Joseph Asagai (the excellent John Clay III), she vies between being an assimilated Black woman for the sake of George Murchison (Mister Fitzgerald), and moving to embrace her ancestry. As the character of Beneath is the vehicle Hansberry provides with humor, Gilbert fine tunes her performance and is funny organically without pushing for laughs.

The ensemble work is seamless, showing prodigious effort as the actors live onstage. Thus, the audience cannot help but love and cheer on the family against Mr. Lindner (the excellent Jesse Pennington who reminded me of a quiet, quirky Klansman from the South, minus a Southern accent). Lindner’s assault on their dignity and chilling comment after he comes back a second time then says goodbye, in addition to his pejorative patting of Walter Lee on the shoulder as he leaves, combines all the self-satisfaction of one appointed to take a “message,” to the good “colored” folk to warn them away.

Most importantly, we grieve with them over the tragedy of Walter Lee (the incredible Francois Battiste), when his “friend” Willie absconds with the money Lena tells Walter to put in the bank. The tragedy is heightened by Tonya Pinkins’ fabulous performance as she cries out to the Lord to give her strength.

As Lena, Pinkins’ heaving call to the Lord is one for the ages. It is a dignified primal utterance which takes everything out of her, after which her hand shakes til the end of the play, for most probably, she suffered a mini stroke. In her fervency not to smash Walter Lee over the head, which he justly deserves, Lena must turn to God for help. Only He can give her the anointed love and patience to see her way through this family tragedy which threatens to swallow up her hope of moving from the “rattrap” ghetto apartment to Clybourne Park’s white neighborhood. Pinkins is riveting, her authenticity just stunning. I couldn’t take my eyes off her.

Walter Lee’s frantic action losing the insurance money, some of which is supposed to go for Beneatha’s schooling, is a bridge too far for Lena. It is no surprise in the next scene where Walter Lee confronts himself and “lays it out on the line” to explain that the culture has broken apart humanity into the takers and the taken, that a discouraged Lena questions going to Clybourne Park. Disappointed and devastated, she condemns herself for stretching out to want something better for her family. Once again Pinkins’ captures the ethos of Lena’s majesty and sorrow with perfection.

As Walter Lee, Francois Battiste seethes just below the boiling point as he builds to an emotional explosion when he realizes Willie has scammed him and Bobo. His is another stunner of a performance. Walter Lee’s abject desperation to become rich eats him alive and destroys his wisdom and circumspection, something which Lena cannot understand about her children’s generation. She notes they have forgotten how far their parents have come to achieve freedom. Pinkins’ Lena reminds her children to be satisfied with the strides their family has made. However, they ignore her wisdom and must learn through experience, a fact which every generation goes through, as Hansberry subtly suggests.

However, the bitter lesson Willie teaches Walter Lee is too heavy to bear. He has been “taken” by a black “friend,” who understands economic inequity born of white oppression, yet sticks it to another black man, exploiting “the opportunity.” Willie is as desperate as Walter Lee, perhaps more so because it forces him to steal demeaning himself and Walter Lee. They have accepted the corrupt white values, Hansberry suggests, and what they have reaped is near emotional annihilation. Willie’s betrayal symbolizes the culmination of every obstacle the family has been made to endure, including Walter Lee Sr.’s death, all thrown back in their faces by Walter Lee’s desperate act of trusting him. With superbly symbolic staging O’Hara has the family stand in the center of their living room, clinging to Lena at this nadir of their lives, as they look into the abyss, the sacrificial money gone.

It is Lena who must sustain them, but to do so, she drains herself dry of life, following in the footsteps of her husband. And the heaving event is so great, she is lamed after it. Throughout, Lena shows ambivalence about the $10,000 check that Walter Lee puts his faith in to change his life. She recalls that Walter Lee Sr. (Calvin Dutton appears at her remembrance), was drained of life trying to make his way through the work load of a low paying job that barely helped them get by. The money cannot replace the value of her husband and the love she has for him. The loss of most of it is a double slap in her face.

Perhaps the most brilliant of O’Hara’s staging occurs with Walter Lee’s speech after he acknowledges Willie has betrayed him. O’Hara has Walter Lee stand in a spotlight downstage to address the audience with a Raisin in the Sun playbill in hand, as he claims he is going to put on a show. Though he is talking about groveling to Lindner, as he receives the payoff to demean himself and not move in to the white neighborhood, he also is referring to the white audience in the theater and beyond its walls.

“The man” which stands for the patriarchy, the corporates and billionaires who demand $two trillion dollar tax cuts of the politicos and expect the little people (everyone else), to pay for it and take up their slack, surely demands Walter Lee “grin and bear” his oppression. Will he decide to take the dirty money Lindner offers for the house, trading his dignity and identity for a corrupted value system? Or will he stand up to Lindner and move into a white neighborhood, breaking down over a century of discriminatory housing?

The speech, a tour de force by Battiste, is breathtaking. It is Hansberry at her most raw, and trenchant. That O’Hara has intuited that Battiste’s Walter Lee should say this standing as if a wild prophet speaking to the audience at the crossroads of his life is just brilliant. Emotionally hitting all the notes, Battiste’s Walter Lee is priming himself for the momentous decision. Does he have the courage to take a stand? Battiste pulls out all stops genuflecting and grinning in a groveling throwback to the days of slavery from which his ancestors came. He shows the family his toady show he will use on Lindner and provokes Beneatha to refer to him as a “toothless rat.”

O’Hara’s metaphorical staging draws us in. Is there one human being who has not experienced shame, feeling demeaned or belittled and who has not internalized it? As Battiste’s Walter Lee spills his guts to the audience, O’Hara offers the opportunity to be there with Walter Lee, to suffer with him, to “get” his terrible pain and perhaps live the moment with him in this cathartic high-point.

O’Hara’ direction and Pinkins’ performance strengthen our understanding of Walter Lee and Lena’s close relationship with his inclusion of Walter Lee Sr.’s ghost who appears when Lena discusses the travails her husband experienced that physically wore him down and killed him. In his stance and posture Dutton embodies the sweat, toil, tears and exhaustion ebbing out of Walter Lee Sr.’s life, as Lena recalls it.

Interestingly, O’Hara also has the ghost appear at the conclusion of the play when the family leaves for their new home. The ghost and Lena kiss, then she leaves and he sits on the sofa of the old apartment as Travis Younger (the wonderful Toussant Battiste), comes back to retrieve his lunch box. Travis stops and considers as Walter Lee Sr. stares out into the audience and we hear a grinding noise, like that of a huge wall being torn down. The movement in the sound symbolizes the breaking of the color bar, as the old apartment and Walter Lee Sr. retreat upstage into the distant past.

As old makes way for the new, the Younger’s Clybourne Park house emerges beautiful, white and shinning. An astounded Travis turns to look at the symbol of their advancement. However, ugly graffiti appears on the house as lights dim. Indeed, as Mr. Lindner warned, the Youngers will suffer abuse at the hands of their prejudiced white neighbors. It is an intimation of the future that is still unfolding today in the present.

There is so much more in this profound reworking of Hansberry’s play, rightly considered one of the best plays ever written. Kudos to the creative team that brings this work to glorious life. They include Clint Ramos (scenic design), Karen Perry (costume design), Alex Jainchill (lighting design), Elisheba Ittoop (sound design), Brittany Bland (video design), Will Pickens (sound system design), Nikiya Mathis (hair and wig design), Rickey Tripp (movement and musical staging), Teniece Divya Johnson (intimacy & fight director), Claire M. Kavanah (prop manager).

There, I’ve said enough. For tickets and times go to their website: https://publictheater.org/productions/season/2223/a-raisin-in-the-sun/

‘Baldwin & Buckley at Cambridge’ at the Public, Review

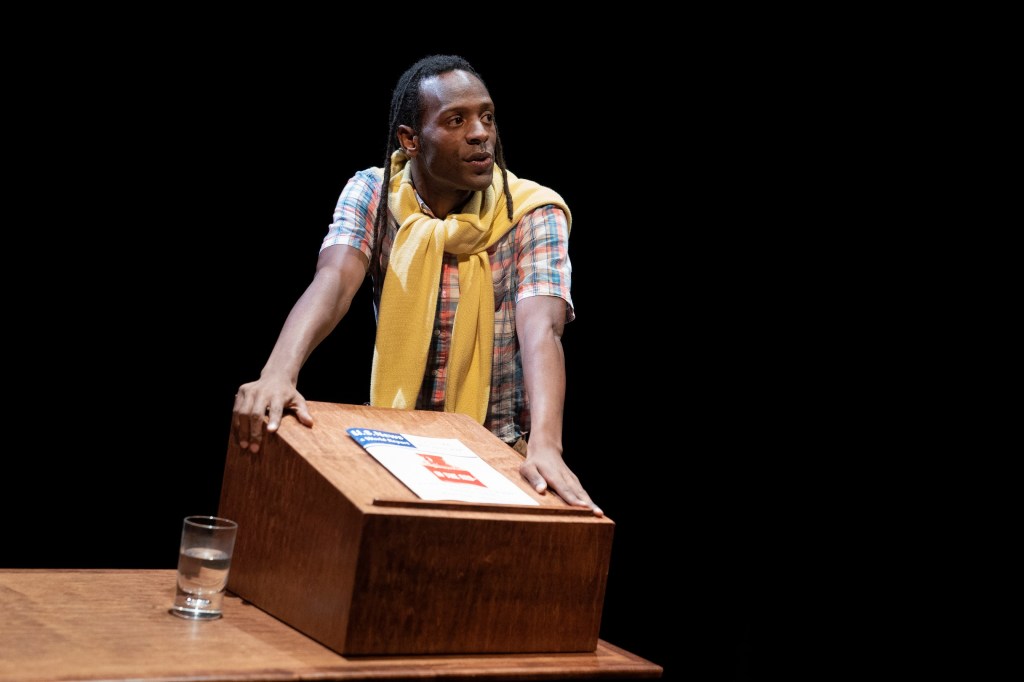

Baldwin & Buckley at Cambridge, the 1965 debate of James Baldwin and William F. Buckley, Jr. at the Cambridge Union, University of Cambridge, UK is receiving its New York Premiere at The Public Theater. You need to see this production presented by Elevator Repair Service (Gatz, The Sound and the Fury) for many reasons. First, it’s vitally important for us in this present moment to hear and understand Baldwin’s criticism about our nation from the perspective of an articulate novelist, playwright, essayist, poet, identified as one of the greatest Black writers of the Twentieth Century. The production, which captures the debate in its entirety, will also help you understand Baldwin’s realistic acknowledgement of American attitudes and sensibilities, many of these carryovers to our present society and divisive culture, whether we are loathe to admit it or not.

The unadorned, bare bones production highlights the arguments Baldwin and Buckley presented at Cambridge in response to the question, “Has the American Dream been achieved at the expense of the American Negro?” With a minimalist set, two desks, chairs, lamps staged with the audience on three sides at the Anspacher Theater, the evening replicates the words if not the tone, ethos or dynamic drama of Baldwin (Greig Sargeant) and Buckley (Ben Jalosa Williams) in their face-off.

It is a worthy triumph of ERS to re-imagine these two titans, one eloquently speaking for Black America, the other a conservative writer and National Review founder. The latter supported a slow walk of desegregation which Blacks must “be ready for,” and were “not yet ready for.” Baldwin’s and Buckley’s perspectives reflected national attitudes, especially after the legislative gains made for Blacks in 1954, 1964 and 1965 which Baldwin didn’t trust because the power structures of the South and North didn’t adequately enforce the laws. In viewing their comments now, as our nation experiences “in-your-face” racism and discrimination, that would overthrow all gains (revealed in striking down Roe vs. Wade and most of the 1965 Voting Rights Act) the concepts in the debate between Baldwin and Buckley are highly relevant and worthy of review.

The inherent drama of the debate, its electric personages, and the crisis of the time eludes the actors and the director. Indeed, perhaps the task is impossible without sufficient artistry, and imagination to suggest what once was, the frenetic and feverish times of the country that in 1965 saw the Watts riots, which Baldwin alludes to at the end of his speech.

When Baldwin and Buckley debated, America was still fighting segregation in the deep South, the effects of which Cambridge student Mr. Heycock (Gavin Price on Saturdays) discusses to introduce Baldwin’s arguments. He mentions statistics quoted by Martin Luther King, Jr. when they conducted a protest supporting voting rights in Alabama. Heycock states, there were more Negroes in jail for protesting than on the voting rolls. He enumerates other statistics. These identified the extent to which Blacks had been excluded from the White society’s opportunities and their aspirations to achieve the American Dream: jobs with benefits, college educations, economic prosperity, home ownership and more.

As both Heycock and later Sargeant’s Baldwin make clear during their fact-laden presentations, in no way was the Black experience in America “separate but equal” to that of Whites. Their lives, their worlds, their perspectives, opportunities and approach to daily living was anything but equivalent.

Though this was especially so in the South, the quality of life disparities also were prevalent in Northern cities like New York, Detroit, Chicago, Los Angeles. There, Blacks were shoveled into the projects branded as a Utopian “urban renewal.” Actually, there was no renewal, as Blacks were crowded into broken-down buildings and crime-ridden ghettos, where rats flourished and the garbage spilled over into the streets. All of these points, Sargeant’s Baldwin mentions, disputing that Blacks have an equal opportunity in achieving the “American Dream,” which is obtain by Whites at Black’s expense.

The debate is a historic call to remembrance and worthy as such, which is why it bears being watched on YouTube, after seeing the Public’s production, directed by John Collins. The YouTube video reveals the unmistakable ambience of Cambridge and the scholars and students present in their formality and sobriety, laughing at Baldwin’s wit and wisdom and sometimes laughing with ridicule at Buckley’s pompousness and stumbles into bigotry.

Indeed, what is absent from the Public Theater production is this sense of moment. Missing is the ambience of setting and the nature of the audience which played a role in relaying the importance of the Baldwin and Buckley debate. These two giants in their own right honored Cambridge with their presence and concern, conveying American voices and perspectives. The gravitas is lacking in the production and is a possible misstep. Though an announcement is made as to the setting, more should have been done to convey the place and time. With a minimum of dramatization, the production wasn’t as dynamic as it could have been.

Creatively conveying time and place was not the choice of ERS or director Collins. Thus, Baldwin & Budkley at Cambridge is uneven. In structure and format the production follows the original debate. The elements are modernized, costumes in modern dress, not the black bow tie and suit worn for the formal Cambridge debate.

Also, somewhat confusing is that Price’s Heycock acknowledges the Lanape Indigenous Tribe who owned the land the Public Theater rests on. Then immediately he segues into the original debate structure. Perhaps as is done with other productions at the Public, a voice over by Oskar Eustis honoring the Lanape would have been less confusing. The separation of the present America from the debate setting is needed so the audience might reflect on the history of the land. After a pause, the setting of Cambridge, 1965 could then be established.

When Heycock finishes his introduction, Cambridge student Mr. Burford (Christopher-Rashee Stevenson) introduces Buckley’s argument, that it is not true that “the American Dream has been achieved at the expense of the American Negro.” To refute this Mr. Burford points out that 35 Black millionaires have achieved the American Dream. This justification that Blacks have attained the dream and not at the expense of Blacks is an example of the convoluted logic that will follow in Buckley’s confused and misdirected arguments.

Burford’s belittling statement in ignoring the huge unequal and disproportionate number of the few wealthy Blacks to numerous wealthy Whites deserves laughter and ridicule. Interestingly, the audience at the Public didn’t respond, as bigoted as the comment was. Possibly the lack of context of time and place contributed to an absence of audience engagement with Burford’s obnoxious statement and at other times during the performance.

Identifying the number of Black millionaires, while ignoring the large percentage of Blacks who live in poverty, evidences the superficiality of Buckley’s arguments which follow Burford’s introduction. As Williams’ Buckley launches into his presentation, we understand that the reality that Baldwin just portrayed about the Black experience in America, will in no way enter in to Buckley’s discussion. Indeed, he dismisses and ignores Baldwin’s brilliant conceptualizations, something which Baldwin intuits that the White culture does to perpetuate the status quo. Throughout his presentation Buckley doesn’t acknowledge that White culture controls, creates and dictates the Black experience. In no way is Baldwin’s picture of reality confronted by Buckley in his disjointed and at times abstruse speech.

Buckley diverges from Baldwin’s statements so that he does not dispute that the American Dream exists at the expense of Black exploitation. He ignores Baldwin’s dense discussion that the American Dream by its very nature in the White culture’s understanding nullifies its existence if Blacks are to be a part of it. For the American Dream to exist, Baldwin suggests from the White perspective, Blacks must be excluded and given little opportunity to achieve it. Blacks can’t be a part because it necessitates exploitation of themselves. Baldwin’s point is that the dream only exists for Whites. Blacks are a part only in so far that they are at the bottom of the power structure, the foundation upon which Whites step up and rise, taking with them all the spoils, all the opportunities.

Sargeant’s Baldwin is wry and not as nuanced, expressive and dramatic as he might have been. On the other hand, Williams’ Buckley is vital, stirring and engaging. Clearly, in the Public Theater production, Buckley won. I found myself dropping out as Sargeant’s portrayal missed important beats. Williams’ sharp edginess and movements kept my interest. Conversely, Price’s Heycock was portrayed with vitality. Stevenson’s Burford was adequate.

Interestingly, after the debate Sargeant’s Baldwin sits with friend and playwright Lorraine Hansberry (Daphne Gaines). Their interchange reveals their close friendship. Unfortunately, the scene is too brief and should have delved deeper. At the very end, Sargeant takes off the mantle of Baldwin in his most authentic moment. He acknowledges the company’s own politically incorrect historic racism when ERS cast White actors to play Black roles in their early versions of The Sound and the Fury. To identify a past that we are still trying to become free of, even the most well meaning of us, seems counterproductive, guilty and fearful. I look forward to a time when theater moves beyond this stance which in itself is disingenuous and “protests too much.”

Clearly, at this time it is appropriate that the debate of Baldwin & Budkley at Cambridge be re-imagined. We are at a crossroads. This is not 1965. We are not in Cambridge, however, the ideas from our racist past that were entrenched, have been redeemed as useful and justifiable for us in the present. At no other time in history having attained what we thought was racial progress, have we been so duped by the residual racism that existed culturally into believing it was harmless. Its dangers have always been there and liberals have been blind to it despite warnings by Black and Brown critics.

Baldwin knew, he saw. The Black reality and White world were as clear as day. He understood that the White reality was convinced of its craven rightness to oppress and suppress Blacks to achieve White agendas at Black expense. Today, this horrific White reality is most visible in law enforcement abuse of Blacks, in the broken justice system that incarcerates Blacks disproportionately, in the exclusion of Blacks in corporate empires, in every institution that harbors systemic racism.

And the economic oppression is growing worse to include everyone except the .001%. These truths existed sub rosa for decades as the gap between the wealthy and everyone else widened. However, it took an egregious and criminally-minded opportunist in former president Donald Trump to justify and promote a resurgence of open hatreds branding the necessity of racist oppression, and authoritarianism ruling the underclasses, using media PR of lies and obfuscation.

For that final reason, Baldwin & Budkley at Cambridge is an extremely vital production which must be seen. For tickets go to their website: https://publictheater.org/

‘Richard III’ Shakespeare in the Park, a Stunning Achievement

For sixty years the Public Theater has kept its mission to offer free Shakespeare in the Park to educate and entertain in the finest of historical traditions that explore Shakespearean theater. This year as in previous years there are two productions Richard III and As You Like It offered in the lovely environs of the Delacorte.

Richard III explodes on the stage with energy and vibrance sported by an amazing and diversely talented cast overseen with stark determination, elegance and astute attention to detail by Tony nominated director Robert O’Hara (Slave Play) in his debut at the Delacorte. The production runs until July 17th, and is a must see event. So plan accordingly. You don’t want to miss what will surely be an award winner whose cracker jack design team blasts one’s socks off with beauty, majesty and thematic coherence.

From the moment Richard III kills Henry VI in a striking, surprising, violent moment on the circular platform center stage, to the end when Richard III in warring armor is killed, Danai Gurira doesn’t miss one beat in her authentic, dynamic and spot-on performance. Pinging every nerve of the malevolent genius of Richard, she never hesitates or pulls back. Throughout she wryly, intelligently gives sideways glances and makes ironic comments to the audience, who she wins over as we enjoy watching her unfold her wicked plans. This, Gurira does with humanity and a comfortable, cavalier attitude sans anger which comes later when her fears grow to maintain her crowning success and the kingdom. Indeed, she compels us to giver her license to endear us to her, as she gradually owns her enemies and seduces us with her frank, honestly expressed intentions.

Of course, these are given to us with jocular aplomb and sly smiles. Meanwhile, she lies, cheats, steals power acting the innocent and bereaved victim as a posture, then winks at us, letting us in on the joke of her machinations of which she is most proud. For with Richard, it’s all about the journey to the crown, not the receiving of the power. Like others we have seen in recent years, once power is attained, she is loathe to keep it and struggles ineffectively and incompetently to maintain what all at court and the officials know she has obtained illegally and through horrible treachery. The parallels to Donald Trump, Gurira and O’Hara have made clear, even gestures of success as she points to the audience as Trump often does and gyrates with a fist pump. At this point in time, the hypocrisy becomes comical, yet Gurira manages to keep the humanity, working an incredible balance and tone via O’Hara’s direction and the ensembles’ magnificent work.

I found this above all to be amazing about Gurira’s performance. We watch enthralled as norm after norm is broken. But we are mesmerized because she doesn’t hesitate nor flinch by caving to hypocrisy and morality. It is only until the last scenes when a cavalcade of haunting spirits of kinsmen and once loyal subjects occupy her nightmares that overwhelming guilt reveals she has a conscience and thus, her blood is required to sacrifice herself as she has sacrificed others.

In Richard’s first speech, Gurira complains of the court that glories in peace, something she throws off because that is not her way of being. This first admission of flaws opens us up to hear more as she aligns herself with the deformity of war which better hides her deformity. It is no small consolation to her that peace and court parties and rejoicing show her up to be a social outcast to beauty, civility, and courtly manners. Thus, we deformed are encouraged to empathize with her as outcasts of royalty, not able to prove lovers, but as she embraces herself will prove herself to be a most incredible, hypnotic villain.

And strangely we marvel as she gleefully seduces her enemy Queen Anne (Ali Stroker) who attempts to kill her, though half-heartedly to instead becomes Richard’s wife seduced and bedded with vanity, though Richard has killed her father and husband. Richard amiably spreads self-hatred wherever he goes. Those he seduces to compromise their integrity, end up hating themselves for their weakness in allowing themselves to be duped, like Queen Anne, his brothers, Lord Hastings, Queen Elizabeth and others.