‘The Who’s Tommy,’ a Nod to the Past, and Segue into the Future

If you are a fan, The Who’s Tommy, currently in its first revival by Des McAnuff, (he directed the show’s original Broadway presentation over thirty years ago), may absolutely thrill you with its exuberant, pulsating electricity and phenomenal musical arrangements. With music and lyrics by Pete Townshend, additional music by John Entwistle and Sonny Boy Williamson II, and Ron Melrose’s music supervision and additional arrangements, it’s a gobsmacking explosion from the past for Boomers, and a scintillating acceleration into the future for Generations X, Y and Z. The production’s hyper-effects leave the music thrumming in one’s mind long after you leave the Nederlander Theatre, where the revival is currently in an unlimited run.

The rock opera which exploded on the music scene in 1969, in long album form was codified as groundbreaking, and eventually was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. Townshend’s chords and story line were memorized by legions in the immediate years after, as critics and fans alike interpreted what the story could be about.

Meanings and symbols spanned from Jesus to Buddha to Townshend’s own avowed inspiration, Meher Baba. The interpretation encompassed a spiritual leader who arcs the soul’s journey and helps mankind and womankind shatter the ego/carnal self to see and feel the spiritual immortality in their humanity. However, mistakenly assuming that everyone’s path toward wholeness can be achieved via the leader’s methods, he makes his followers do exactly as he did, making them suffer. His followers rebel and ultimately reject and metaphorically crucify the one they formerly idolized. The reward is not worth the path of suffering, denial and dedication to get there, they feel, as they take out their suffering on Tommy’s parents while he escapes to solitude and the seeker’s path at the conclusion.

Of course, these interpretations reflected the progressive spirituality and dedicated movement toward liberation of the late 1960s-70s, heavily influenced by psychedelics, flower power, gurus and shamans from various cultures, belief in peace-not war, and the Jesus Freaks movement (not the same as carnal, conservative evangelical, political Christianity today). Duly inspired, the maverick British film director Ken Russell created his hybrid fantasy drama musical based on The Who’s titular album. With an exceptional cast (Oliver Reed, Ann Margaret, Roger Daltrey, Tina Turner, Elton John, Jack Nicholson), Russell maintained the story which centered around traumatized Tommy Walker (Roger Daltry in the film). The literal story follows from the film and subsequent productions, Broadway (1993), through the first section until the latter part of Act II.

This latest Broadway revival veers off after the healed Tommy establishes his fan base and seeks to “correct” them with his methods. Townshend and McAnuff’s book sterilizes the retributive, shocking ending. Tommy purists may not like how the book truncates the force of the last half. “Tommy’s Holiday Camp” is cut, as is the subsequent brutality visited on his fans and parents. Some songs are added, without the same musical strength as those in the original album. The spiritual concepts are also minimized. Instead, this version emphasizes the visual, futuristic design spectacle of the production by David Korins (scenic design), Amanda Zieve (lighting design), Saragina Bush (costume design), Peter Nigrini (projection design).

It suggests video gaming culture and the small screen iPhones and Androids forever before our faces. In the suspended lighted frames of all sizes in various scenes that generally frame the story, is the theme that society and parents frame us. These frames echo and the central mirror framed by lights that Tommy repeatedly looks into and looks out of. The effect echoes the culture’s “branding,” boxing in everyone to fit in to get along.

Not having seen other productions, or The Who in concert, the updated, futuristic spin for me, carried its own message, themes and warnings. Certainly, with its high-tech projections and minimalist frame lighting, echoing the frame of the mirror which Tommy is obsessed with and his mother eventually shatters, we are reminded of our current culture’s preoccupation with gaming, selfies, ego, self-importance and encouraged selfishness. Especially through the staging and design, this version emphasizes such nihilistic obsessions and the danger of small screens whose App platforms brainwash, distract and seduce.

This theme moves throughout this revival’s technical aspects which align with our own culture’s deluded “deaf, dumbness and blindness” and the near cultism inspired by hand-held devices. These have increasingly disassociated us from our own natural environments and directed us toward a dystopian, fabricated world view of division, hatred and insult or complete distraction and entertainment with the effect of protecting adherents in their own information silos. This parallels how Tommy protects himself with his psychosomatic illness.

This version begins with Peter Nigrini’s fine production design that spins a black and white collage backdrop of the setting for 1941. Against that backdrop acted out are the Walker’s marriage, the German POW Camp, etc., as the Overture plays and the company sings.

Mrs. Walker (the sweet voiced Alison Luff whose climactic moment of shattering the mirror is delivered forcefully), gives birth (“It’s a Boy”) after which Tommy’s father, Captain Walker (Adam Jacobs), is believed to have died, though the war has been won (“We’ve Won”). Understandably, Mrs. Walker takes another lover (“Twenty-One”), but when Captain Walker returns to see his wife in the lover’s arms, he kills him in front of four-year-old Tommy (Cecilia Ann Popp and Olive Ross-Kline alternate days). Told by his parents to suppress what he sees and hears about the manslaughter, Tommy turns himself “deaf, dumb and blind” in a crazed psychosomatic obedience and rebellion against his warped, fearful parents (“Amazing Journey”).

As Tommy grows up unresponsive and uncommunicative with his parents and his environment (Quinten Kusheba and Reese Levine portray the 10-year-old Tommy alternating days), he is further traumatized by his pedophile Uncle Ernie (John Ambrosino’s part is sanitized in the song “Fiddle About”), and sadistic cousin Kevin played by the superbly arrogant, wickedly sinister Bobby Conte, who gloriously sings as the perfect, cruel foil to Tommy’s innocent. Both villains “babysit” Tommy as his parents neglect him (“Do You Think It’s Alright?”).

The actors portraying the younger Tommy are incredible as automatons. Their performances represent the result of horrid parenting and enforced objectification, when children receive orders then respond/rebel in original ways. In the story Tommy is an objects to be played upon and pushed around. I found this interpretation by McAnuff frighteningly symbolic, giving new meaning to parental abuse, neglect and force-feeding an obedient image, “acceptable” to his parents. They remain obtusely unaware about their integral part in suppressing Tommy and fashioning him into a non-person who screams “See me, Feel Me,” for he wishes to be free from the soul bondage.

Tommy’s future, older self is portrayed by the stellar Ali Louis Bourzgui, whose voice shatters consciousness itself with its phenomenal power and nuance. McAnuff has him stand in the light-framed mirror, reflecting back his alter-ego when the younger Tommys look in the mirror, their backs to the audience. This is open to interpretation. One possibility is a metaphoric representation of hope of who Tommy can become, including the whole person, free and in touch with his spirituality.

Though Tommy diminished three of his senses to suit his parents’ wishes, he compensates with an enhanced sense of touch and his sixth sense tied to his imagination (“Sensation”). A series of fateful events leads Tommy to become a pinball champion with his energized sense of touch. But despite this compensation and rise to fame, his parents want him to check in with reality, tired of the robot they created unaware. This leads to a series of interventions at a clinic and at a place where Tommy can receive drugs from the Acid Queen (Christina Sajous).

This wild scene in what looks like a crack den out of a Spike Lee Joint (film), reveals Sajous to be a desperate addict doing the bidding of her pimps. Jacobs’ Walker relents at the last minute and leaves with Tommy. It is another veering off of the original album and Russell’s film (with Tina Turner as the Acid Queen in an unforgettable performance in the film). This redirection which purists will object to de-glamorizes the positive effects of psychedelics in what is now becoming treatment for PTSD survivors and those with severe depression. However, sanitizing the Acid Queen scene also emphasizes the father’s desperation to have his son cured. He’ll try anything, but then realizes “anything” has its own potential horrors.

Obviously, Townshend and McAnuff keep the audience away from the disturbing and unsettling as much as possible, reflecting the conservatism of our times which ironically has given rise to the runaway chemicals of the pharmaceutical industry, controlled substances and highly addictive prescription medications like oxycontin and fentanyl. Both highly addictive “meds” have caused thousands more deaths than “orange sunshine.”

“Pinball Wizard,” the spectacular number sporting contrasting colors, flashing lights, searing projections and uber-technicals, as the grown Tommy “shows his stuff,” is breathtaking. Sung by Bobby Conte and the ensemble (with a nod to Elton John in the film by an unnamed “Local Lad” who belts out the opening salvos of the song and is fantastic), the audience experiences a gyration of emotions as the first act ends. The music has elevated and mesmerized, and one is left anticipating Act II with the timeless rock music pulsating through minds, hearts and bodies.

The first Des McAnuff production of The Who’s Tommy in 1993 starred Michael Cerveris as Tommy. The production, nominated for 11 Tonys, won five, including Best Original Score for The Who co-founder and musician Pete Townshend. The revival will surely be nominated, principally for its phenomenal find in the latest Tommy, Ali Louis Bourzgui, whose penetrating voice, compelling presence and powerful mien establish Tommy in all aspects of the character, implying sensitivity, charisma, spirituality and the ability to mesmerize and lead.

However, in updating The Who’s Tommy to make it relevant for our time, the spirituality and wisdom of the album’s meaning is inevitably softened to encourage a frightening look at our contemporary culture, albeit also softened. If anything is at fault with this version, though there is too much that is great which does mitigate any faults, a flaw is this. McAnuff didn’t go far enough with his vision to expose the importance of Tommy’s message-the need to return to spirituality, with direct references to the current ubiquitous technology, fake, hollow Christianity, and memes that seek to globalize, pasteurize and with cacophonous, information overload, overwhelm the importance of original unique voices emerging from the human spirit.

The finale attempts to do this. It happens as the audience and cast, who stands on the edge of the proscenium, sings “See Me, Feel Me”/”Listening to You.” It is enough, yes, but it also isn’t. With so much at stake in our present culture, with so great a need for people to return to inner healing and spiritual wisdom, McAnuff’s softening of the inherent villainy and spiritual revelations of the original album with an incomplete update of the cultural relevance, might be a lost opportunity. Regardless, I loved The Who’s Tommy.

Kudos to those not mentioned before. These include Lorin Latarro (choreography), Steve Margoshes (orchestrations), Charles G. Lapointe (wig & hair design).

The Who’s Tommy. Nederlander Theatre, 208 W. 41st. St., New York with one intermission. TommyTheMusical.com

‘Water for Elephants’ a Sensational, Poignant, Uplifting Spectacle

Based on the titular novel by Sara Gruen, Water for Elephants, excitingly directed by Jessica Stone, currently runs at the Imperial Theatre until September 8th. The production is a circus musical about redemption, love, courage and faith. With a book by Rick Elice and songs with a variety of dynamic musical styles and empowering lyrics by Pigpen Theatre Co., this is one of the finest, most rousing musicals to land its premiere on Broadway.

Water for Elephants richly incorporates the spectacle of the circus with stylistic artistry and well choreographed, impressionistic, acrobatic, aerial beauty. The company particularly embodies the spiritual essence of the beloved animals that are integral to the acts that barely keep solvent the foundering Benzini Brothers Circus, taken over by ringmaster/owner August (the excellent Paul Alexander Nolan).

However, before the spectacle begins, at the top of the musical, a wizened, grey-haired, tall gentleman, Mr. Jankowski (the fine Gregg Edelman), appears. He is serenaded by ghosts of the past (Prologue) which remain obscure in our understanding until Charlie (Paul Alexander Nolan doubles in two roles), returns Mr. Jankowski to the present from his reverie, and Jankowski good naturedly comments that he enjoyed O’Brien’s One-Ring Circus. As June (Isabelle McCalla) and Charlie make sure everyone is packing up, a few turns of dialogue later, the elder gentleman comments that June’s horse could use “a stress test.”

Immediately, we realize that Jankowski’s knowledge is particular. And when he says he is there alone because his kids were too busy to come with him, and he’s escaped from the “home” and that will put the nurses in a tizzy, we are intrigued by what deep element in his psyche has brought him to this small circus. Affable and pleasant, Jankowski ingratiates himself with Charlie and June. Warmed up by his inside knowledge of circus jokes, Charlie says Jankowski can use his phone to call a cab to return him to the “home.” In the interim, June offers to show him around as they discuss his involvement in the circus of yesteryear and the differences between then and the present-day. Finally, Jankowski, a former animal vet, offers to look at the mare that “needs a stress test.”

From this segue, the arc of development begins and Edelman’s Jankowski genially and intelligently narrates his involvement with the circus. As we move into the flashback, Edelman deftly walks us into the past. It is during the depression and Grant Gustin portrays Jacob Jankowski as a young man. In an amorphous scene of memory and voices, the older man sees his younger self reacting to the news of his parent’s death in a car accident, after which he was orphaned and left homeless. The powerfully voiced Gustin’s Jacob lives hand to mouth fending for himself. Hoping things will be better somewhere else, his destitution places him with other hobos on a train going wherever the wind blows them, (“Anywhere/Another Train”).

Jacob’s fellow riders Camel (Stan Brown) and Wade (Wade McCollum) are ready to throw him off this special train, but Jacob roundly stands up to Wade’s bullying aggression. Afterward, the two men who are roustabouts tell Jacob he hopped on a circus train and he can ride with them to the next town and stay for a day by making himself useful. There is fierce competition for every job, and he needs to distinguish himself to stay around permanently.

The stylized sets by Takeshi Kata in this scene of fast pacing movement are scaffolds on rollers which suggest a moving train with the help of the company, who create the bouncing motion which suits the rhythms of the music. Camel, who empathizes with Jacob, is the one who persuades Wade to allow him to stay for one day. Since Jacob elects to work with the menagerie, Camel tells him after they arrive in Utica and start setting up, he can earn his day’s keep by shoveling “s%$t.”

Director Jessica Stone and her creative team, which includes Shana Carroll’s circus design, Jesse Robb & Shana Carroll’s choreography with Mary-Mitchell Campbell & Benedict Braxton-Smith’s music supervision and arrangements, reimagine the interior, backstage world of the circus, of roustabouts, and the odd mix of personnel attracted to the nomadic, unique, showmanship of circus performance. In the musically synchronized “The Road Don’t Make You Young,” Jacob tours the circus and sees the insider’s scoop. The company of singers and acrobats swing mallets to stake the ropes for the Big Top and do daring twists and thrusts high into the air to commit muscular feats that take one’s breath away and rival the masters of Cirque du Soleil.

Jacob is nonplussed, figuring he will only stay one night, but is amazed to meet Agnes the Orangutan (Alexandra Gaelle Royer cutely re-imagines the reputedly smartest ape). Introduced to Barbara (Sara Gettelfinger), the mothering lead dancer of the “cooch tent,” Barbara tells him to get some grub and act as bouncer. Wade (August’s deadly right arm), renames her act to “Barbara and the Bally Broads,” and elevates them from the side show to the Big Tent to do “less strippen and more dippen.” Gettelfinger in a minor part plays it to the hilt.

As the song continues, Jacob, nicknamed Jake, also meets knife thrower and clown Walter (the humorous Joe De Paul), and Queenie his dog (a fluffy, long haired, hand puppet skillfully authenticated as a pooch by whomever “handles” her). By this juncture, Jake has met all those, who have been worn out by traveling the adventurous, road except the puppet master who keeps all in line. To conclude “The Road Don’t Make You Young,” owner August Rachinger presents himself center stage as the Broadway audience goes back in time to become the Benzini Brothers audience. In typical one-up-man ship razzle dazzle, Nolan’s ringmaster sings, “You wanna see something to set your spine tingling, something that blows Ringling out of the Ring?”

We question. Is he for real or just another blowhard exaggerating that chaff (the empty hull of a grain of wheat) is the meaty kernel of substance as he pretends his circus is finer than Ringling Brothers?

Unlike the quaint audience of the 1930s, who could not fathom black holes in space, television, quantum physics, cell phones, space stations orbiting the earth, Social Media and AI, we are the audience who experiences daily scientific wonders. What we’ve seen thus far on stage makes us understand August’s drive to be great in a time frame that is 90 years in the past before the dropping of the atom bomb. Additionally, we must consider that the parochial audiences of that time may rarely have seen a live lion.

Our disbelief at August’s pronouncement is gradually suspended when the action moves back to the present with the elderly Jankowski. Charlie and June act amazed when he tells him that this circus was the famous Benzini Brothers of 1931. The crux of the story, how the foundering Benzini Brothers becomes THE Benzini Brothers of 1931, an outfit which made circus history, but not in a good way, is the substance of Jankowski’s tale.

The turning point for the circus and Jankowski’s narration begins at the encouragement of June and Charlie in the present. They want to know what happened. It is then Elice’s book returns us to the past, when Jake hears the limpid voice of Marlena (Isabelle McCalla also doubles as June). She coaxes and attempts to calm the ailing Silver Star (the horse she rides who brings in the crowds), out of his pain by singing, “Easy.”

This is an exceptionally moving number as Antoine Boissereau infuses the agony of the horse with liquid movement aerially, as the white drapery flows with choreographed simplicity to effect his spirit struggle to stay alive despite his pained flesh. Jake is emotionally moved by Silver Star’s pain and the soulfulness of Marlena’s healing song. However powerful Marlena’s love is, Silver Star needs weeks of rest and recuperation to return to the center ring. If he doesn’t heal he will be lame, a death sentence for a star horse. Jake, uses the knowledge he has learned at Cornell as a vet, and his father’s experience as a vet. He tells August, who Jake finds out is Marlena’s husband, that the situation is dire for Silver Star.

August has him mercifully kill Silver Star which is a dramatic moment created by the Boissereau’s artistry. By that point August realizes Jake’s value and offers him a job. Jake avers because he realizes the pressure and tension he will be under having fallen for Marlena and having to live under the watchful and sinister monitoring of August whose behavior, at times is cruel and bellicose. When the train arrives too late at Wilkes-Barr, Pennsylvania where they try to get a replacement horse, they discover only Rosie is left for them to buy. August purchases her, and then is told she is an elephant, and they discover a truth her caretaker shares after purchasing her. She is one of the dumbest creatures anyone has ever worked with.

Humorously, not only has Jake fallen for Marlena, he falls for Rosie, who appears first as a trunk, then as various parts of an elephant in a clever “keep the audience wondering” if she will ever appear as the whole package. Interestingly, there is a meld of time, of present and past so that the elder Jankowski and Jake and Marlena sing the praises of Rosie (“Ode to an Elephant”) in another of Jankowski’s reveries.

With transformative hope, Marlena and Jake work together with Rosie as August suggests, while he sinisterly comments that Jake will never have Marlena and in effect threatens him away from her. Nevertheless, Rosie, Marlena and Jake work to try to get Rosie to do tricks with Marlena. In these sequences with Rosie the past is the present. Mr. Jankowski relives the hard work they go through with Rosie, who just doesn’t get much of what they are trying to teach her. (“Just Our Luck”) (“I Shouldn’t Be Surprised”)

Meanwhile, if they can’t get Rosie in the center ring with Marlena as their main attraction, the circus which was foundering will completely fail. They need a miracle. Wisely, Stone teases the audience with what it wants to see, Rosie in full regalia as the beautiful elephant that all, including the company, have been singing about. Tantalized, we see the shadow of Rosie whole, but have to wait for her in fullness, until after the romance between Marlena and Jake blossoms in a kiss that happens almost unconsciously and whose “tell-tale” signs of lipstick alert Camel to warn Jake that he won’t be able to handle the trouble August will bring upon him for stealing the affections of his wife. Likewise, Barbara warns Marlena off Jake. However, both cannot help themselves.

Despite Marlena not getting Rosie properly trained for her star performance, August pushes the issue because they are desperate for the money the act will bring. In “The Grand Spec” Nolan’s August and the company superbly whip up the crowd as we anticipate seeing Rosie do “her thing.” When he is left standing with no stars emerging, the humiliated August runs backstage and attacks Rosie and beats her, trying to get her to move. We hear her pained trumpeting cries, and then she defends herself and knocks down August. She is ready to stomp him when the miracle happens.

Jake in the twinkling of an eye reacts and Rosie stops herself from killing August whom she hates. The day is saved and the audience finally sees Rosie in full form. She is awesome in all her glorious, sensitive puppetry thanks to Caroline Kane, Paul Castree, Michael Mendez, Charles South and Sean Stack. “The Grand Spec” concludes and August finally becomes what he’s dreamed of being, the proud, successful “ringmaster extraordinaire.”

However, this achievement is at great cost, for he realizes he has harmed his relationship with his wife. Jake’s success with Rosie and August’s own cruelty and jealously have pushed Jake and Marlena together. She hugs Jake celebrating their success. Though she blows August a kiss, his inferiority and insecurity make him feel the loser. Nothing she can say and do will arrest his thoughts that Jake and his wife are lovers, though nothing but a kiss and hug has happened between them.

Thus, one problem is solved, however, unchecked psychologically, August, who should be thrilled with Rosie and Marlena’s sensational act, is driven toward distrust and anger. He drowns in his own bitterness that the reason why the act with Rosie is a success is because of, Jake, who has become invaluable.

Act II unfolds as the conflicts increase among August’s circus people and himself as well as August, Rosie, Marlena and Jake. In the first act we have a clue to August’s character (“The Lion Has Got No Teeth”); he feels he is a worthless fake. Though he glories in it and embraces his lies, this attitude does nothing to uplift him. August allows his envy of Jake, who is his superior in attitude, personality, education and kindness to animals, to be his undoing. Instead of realizing Jake and Marlena love each other and it’s time to move on, his cruelty and thuggery (we see how Wade, his lackey, acts out August’s evil wishes) cause him to seek vengeance. This spills out onto others in his company, and we note that he becomes so loathsome, that he cannot even stand himself.

Nolan is the perfect, nuanced villain that we can understand because Elice’s characterization gives the actor so much to work with. Likewise, with the other characters who are strongly portrayed in song i.e. (“I Choose the Ride”), a song which Camel leads beautifully, we understand the choices the characters make. These ultimately lead to their victimization by August who becomes more and more tyrannical and vengeful without good reason. How he moves against Walter and Camel is terrifying, and McCollum’s Wade haplessly allows himself to be ill-used and exploited by August.

Once more we are reminded that evil flourishes because potentially good people do nothing to stop it. In Wade’s instance, he services August’s wickedness for his own purposes, willingly becoming his slave.

The energy and enthusiasm of the acrobatic dancers of Act I are even greater in Act II. Importantly, their action arises organically from the sequence of events that occur. Nothing the creative team does seems extraneous or out of place in the circus world. And it is a delight to watch their expertise and phenomenal talents singing, dancing and doing exploits during the various musical numbers which range from jazz, country, blues, ballads and more. The score and complex lyrics by Pigpen Theatre Co. have been reworked, honed and refined to precision.

This is one to see for the outstanding performances, the acrobatics and aerial spectacle which are extraordinary. The circus design makes sense in Stone’s creation of a small-time circus of 1931, run by a flawed ringmaster who attempts to keep things together, despite his interior brokenness. The director’s staging capture’s the novel’s ethos and heightens all the characters’ vulnerabilities. August’s failings make him the perfect foil for cruelty and exploitation. His darkness is made all the more evident in contrast to Jake, who in every way is his opposite, especially in his humility, gentility and decency.

There is one scene taken out of Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables, which clues in the differences in the soul conflict and morality between August and Jake. Jake has the opportunity to kill August while the ringmaster sleeps. His goodness wins out and he stops himself. It’s a marvelous inclusion in an intricately woven, profound musical about individuals pressed by circumstances toward the abyss, until they free fall into their own inevitable demise.

Kudos to those not mentioned above which include David Israel Reynoso’s costume design, Bradley King’s lighting design, Walter Trarbach’s sound design, David Bengali’s projection design, Campbell Young Associates’ hair & wig design and Ray Wetmore & Jr. Goodman, Camille Labarre’s puppet design. Finally, the music was compelling thanks to Daryl Waters, Benedict Braxton-Smith, August Eriksmoen’s orchestrations, Music Director, Elizabeth Doran and Music Coordinator, Kristy Norter.

Water for Elephants. Imperial Theatre, 249 West 45th Street, between 7th and 8th. 2 hours forty minutes with one intermission until September 8th. https://www.waterforelephantsthemusical.com/

‘An Enemy of the People’ Brilliant, Drop Dead Tragicomedy With Jeremy Strong, Michael Imperioli

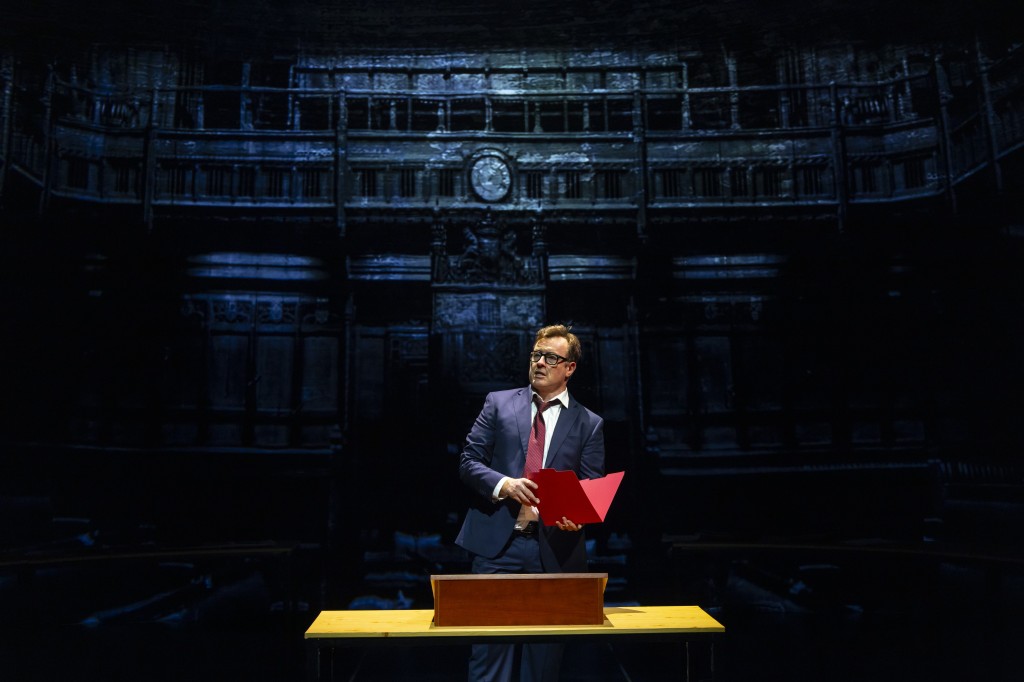

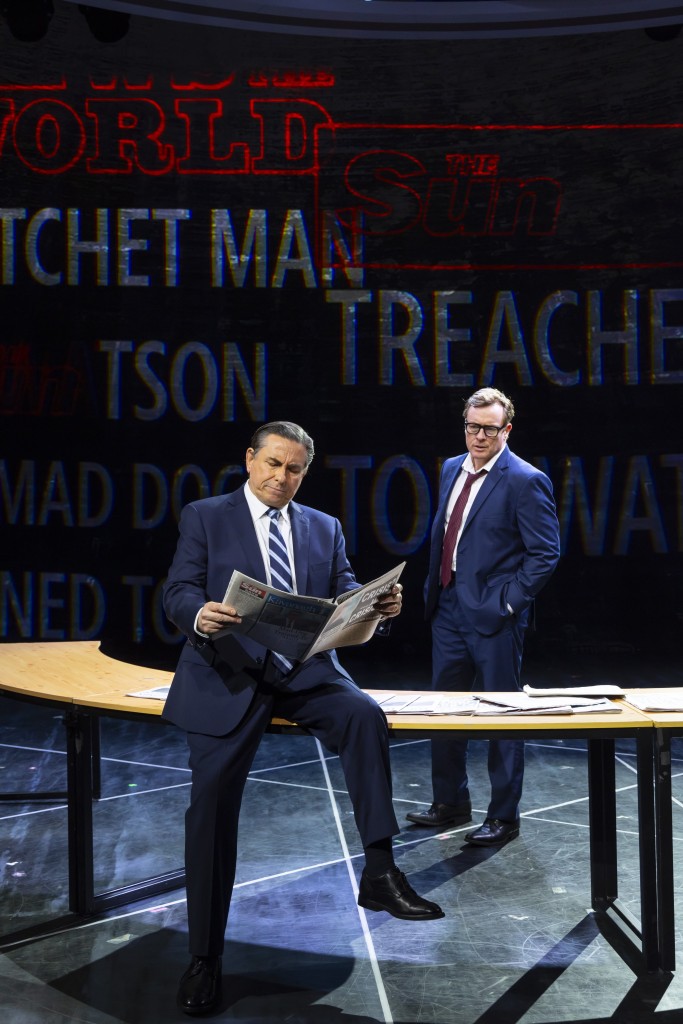

In Amy Herzog’s adaptation of Ibsen’s sardonic An Enemy of the People, currently at Circle in the Square for a limited engagement, we are treated to a modernized version of a work whose timeless verities ring true for us today. Aptly directed by Sam Gold (A Doll’s House Part 2), Jeremy Strong (TV: “Succession”) as Dr. Thomas Stockmann and, Michael Imperioli (TV: “White Lotus”) as his brother, Peter Stockmann, go head to head about a subject that should concern every politician and citizen on the planet: clean, potable water.

In adequately slimming down Ibsen’s five act play to highlight important themes that are taken out of our current headlines, Amy Herzog confirms her penchant for adaptation. Successful with the process of refining, to trim the salient dialogue and concepts of a classic work, Herzog’s minimalist adaptation of A Doll’s House was nominated for a Tony Award. Likewise for An Enemy of the People, Herzog tames the unwieldy Ibsen sentence construction and vocabulary (sometimes hampered by translation from the Norwegian), so its clarification provides accessible, trenchant, stark meaning with a greater impact than the work may have had in an original translation.

Other changes in characterization compact the play’s crystalline focus. Conjoining two characters (Petra and Mrs. Stockmann) into just daughter Petra (Victoria Pedretti), Herzog humanizes Dr. Stockmann, who misses his dead wife, and is gratified that his remaining family is close and supports him. Reinforcing Petra’s identification with her father, Herzog intensifies Stockmann’s dilemma and persecution which becomes Petra’s problem as well. So we appreciate her defense of her father and courage in braving the victimization and town’s retribution after the doctor attempts to save the town from itself by blowing the whistle about a nearby spa’s contaminated water supply.

Herzog emphasizes the situation and brings it rapidly to a crescendo. It begins with acknowledgement of Stockmann’s heroism by his friends. The fine scientist and researcher sends the nearby resort’s water sample to the university lab which affirms disease-causing, killing bacteria in the water. In Europe those who would visit spas for treatment, sometimes would “take the waters,” meaning drink the waters for their reputed, curative healing effects. Stockmann has discovered that if the patrons sip the “healing” waters, the tourists will become deathly ill. If they bathe in it, perhaps the polluted water won’t be as immediately disastrous, but it will be dangerous. This is Ibsen at his sardonic best and the message is meaningful for us today, (water damaged by PCBs, microplastics, hormone disruptive contaminants). Though Ibsen wrote the play over 140 years ago, little seems to have changed.

When Stockmann’s more liberal friends, newspaper editor Hovstad (Caleb Eberhardt), his assistant, Billing (Matthew August Jeffers), and even Aslaksen, Chair of the Property Owner’s Association and printer (Thomas Jay Ryan), hear of Stockmann’s prescient action, they deem him to be heroic in “saving” the town. During their discussion we find out that both Hovstad and Billing resent the wealthier investors having come from impoverished backgrounds; they encourage the doctor to publish the report. Additionally, Aslaksen, wants to hold a dinner party and present Stockmann with a small award. Aslaksen, a self-declared “man of moderation” says, “nothing too flashy, we don’t want to ruffle any feathers.

To complicate the situation, Stockmann’s father-in-law, Morten Kiil (David Patrick Kelly), who is still alive and a wealthy man, owned one of a number of tanneries near the spa area. Apparently, Kiil and the other tannery owners “forgot” to properly dispose of the chemical runoff used to cure the hides and the poisons have seeped into the water table. (Think of Jonathan Harr’s book and adapted film A Civil Action, about the pollution of the Woburn, Massachusetts water supply that sickened and killed children and families.).

Petra reminds her father that he suggested before the construction of the resort that they make adjustments for such a possibility because Stockmann feared the tannery’s proximity. However, his brother, Peter (the town mayor), the investors and officials shot down the doctor’s idea because of additional cost and delay. Their wants were understandable; the sooner they opened the resort and spa to make money and bring tourists in droves to the town, the better. Indeed, the town, in anticipation of the spa’s opening in the summer has grown more prosperous and the people are looking forward to servicing the tourist trade that the spa will bring.

Clearly, money “trumps” the viability and security of the spa. Stockmann’s science and the safety and sanctity of human life are in bondage to financials and commercialism. The developments that follow after Stockmann receives the lab report hang in the balance. Will his boss and brother, the mayor and investors agree that the situation warrants rehabilitation of the baths, though that might jeopardize the town’s commercial viability? Or will the mayor and investors hold the line that the spa and resort be opened and celebrated, despite the potential harm to come? In other words should the truth be exposed or covered up?

The brothers are on opposite sides of the dilemma; one represents science, the other the town’s economic prosperity. A critical factor is that Peter is Thomas’ boss and Thomas answers to him. As Dr. Stockmann lives for his work, so does his brother Peter, who has never married and demonstrates overweening pride as the mayor servicing the richest, most prosperous citizens. If they were at odds with each other before, with Peter ignoring his brother’s scientific suggestions and criticism of his “liberal” newspaper friends, their conflict explodes after the doctor confronts Peter with the report.

Unfortunately, the doctor’s idealism and self-righteousness has blinded him, as Peter’s greed, self-importance and his rich friends sway him beyond human decency. Peter appears to hold all the chips in this poker game. Their struggle is an iconic one and Gold’s direction and Strong and Imperioli’s acting are on-point superb during their interactions and arguments and especially at the town meeting.

Of the doctor’s three friends, Aslaksen is the one who anticipates that various townsfolk may not perceive Stockmann as a hero. And indeed, when the mayor reads Stockmann’s report, he takes it personally as an attack based on resentments stemming from their childhood. Beholden to wealthy interests, Peter actively dismisses the gravitas of what Thomas suggests and refers to his brother’s pronouncements as “speculation and wishful thinking,” and he insists the doctor’s attitude is “spiteful and childish” for cutting off the town’s “only” source of income.

From his perspective the proof screams at Thomas about how dire the situation is. Thus, the doctor expects his brother to retrofit the baths and delay the opening of the spa, though he has not researched the practicality of how long it will take and how much it will cost. The situation can be mitigated if the two sides agree to tackle the problem rationally and intelligently. However, both brothers cast it as an either or situation and Peter is predisposed to cover up the noxious, infernal truth and proceed with the spa’s poisoned-filled opening.

The genius of An Enemy of the People is the way in which the situation and character interactions reveal social and personal dilemmas. Do we uplift human rights supporting the sanctity of life and security for all as the doctor does? Or are rights subject to economic and class background and curtailed accordingly, as Peter wishes? Are we generous and life-supporting or selfish and nihilistic? Are those with money truly superior or is their arrogant, self-importance riddled with flaws because to value money and power over human life is suicidal folly that leads to catastrophic, karmic consequences?

In this play, Ibsen reveals the perniciousness of toadying to class and money at the expense of life and health. And so it goes with Peter, the mayor, who bows to special interests despite the apocalyptic moral imperative that the spa will kill instead of heal. According to the mayor, the cost and delay will bankrupt the town. He manipulates and threatens Thomas’ friends Hovstad, Billing and Aslaksen so that they turn against Thomas to “save” the town from the financial debacle that will occur if the spa closes.

As forces converge against Thomas, and his friends who once stood by him back away from his facts, we note that financial viability is the only consideration, when it doesn’t have to be. The arguments given settle in the “benefit” to the town’s prosperity which will be destroyed if they take two years to retrofit the spa. The spa supporters affirm that surrounding towns will jump in the gap and create their own resorts and wipe them out competitively by the time they finish their corrections. If they cover up the truth, at least the town will prosper commercially and the investors will receive an immediate return on the investments.

In their arguments, not one of the spa supporters, Stockmann’s friends or the mayor consider that tourist deaths and subsequent lawsuits could force the town into bankruptcy. Even worse, the scandal of a cover-up and eventual publicized expose will necessitate investigations and the public humiliation and outcry that such was allowed by the mayor, etc., destroy the town’s reputation and revenue for a long time to come. The gaslighting notion that the doctor’s facts are “speculation” is actually the fantasy (“wishful thinking”) that the bacteria and poisons in the water are not harmful and/or don’t exist. The investors, town and mayor are “damned if they do, and damned if they don’t.”

Rather than correct their attitude and behavior, Peter and his supporters double down on their initial dereliction in not following the doctor’s suggestions. They turn on him blaming him for the situation which they negligently in a criminal dereliction of duty refuse to believe and act on.

Strong’s doctor gives an impassioned speech to Peter, Hovstad, Aslaksen and Billing. He prophesies that he will present the truth at a general meeting and save lives regardless of their position not to publish the report. The town should be able to hear and decide the best path to take. At the end of his arguments with Aslaksen, his brother and the others he states, “I have faith in the people of this town. You can fire me, you can shun me. But you can’t stop me from telling the people the truth.” Strong’s performance is authentic; we believe him and hope with him. It is a superbly unforgettable dramatic moment.

It is also an excellent place to create “the pause” (not an intermission), which lasts five minutes, then segues into the town meeting where Stockmann presents the report. The playing area is converted from Dr. Stockmann’s atmospherically lit house and study, into a well-lighted bar where drinks (aquavitae) are served to the audience. Gold has dynamically staged this segment so that audience and actors mingle and imbibe for the five-minute interval. The atmospheric lighting of the first half of the production with gorgeous antique lamps from that period is replaced during this “pause”. The theater’s regular lighting is turned on as the drinks are served. It stays on, then, as the town meeting gets underway, and the play resumes with lights down, Dr. Stockmann confronts the mayor, his former friends and the townspeople.

This is genius staging because during the “pause,” Gold moves us from the past to the present in a time meld, and we are reminded of the currency of this play’s situation and themes.

Then the town meeting ensues. It is terrifying and fascinating. The mayor, Hovstad and others shut the doctor down with loud verbal muscling. When Thomas stands up to them speaking the truth, whipped up by the mayor and others, the townspeople repeat the others’ refrain that Thomas is “an enemy of the people,” and physically beat him. Strong’s performance and the ensemble’s counter-performances are incredible.

As we stand in the doctor’s shoes, we identify with his untenable situation which is beyond irony. This is especially so after he is pummeled with buckets of ice (the symbolic equivalent of a stoning) thrown on top of his head. Strong’s Stockmann rips off his shirt and offers his life for them if only they would accept the truth. The irony is complete. The townspeople and his brother want their fantasy. His life and their own lives are worth nothing. Money is everything. They believe that the spa will bring prosperity and money though they may not live to see it. They can’t handle Thomas’ “facts.”

We have seen this picture played out before in the COVID political botch job of the former president, who, like Peter the mayor, eradicated the deadliness of the virus with his lies and misdirection, as the US charts the largest number of COVID deaths globally to date; yes, people are still getting COVID and dying from it. The townspeople’s rejection of Stockmann’s facts hyped up by the mayor and his cohorts parallel MAGA’S convenient rejection of the truth for “alternate” facts (conspiracy theories) which they rabidly cling to in a morbidly cultish intractability whipped up by MAGA politicians. Then as now, science is rejected by those who wear their lack of education and ignorance on their sleeves, as the facts become others’ “wishful thinking.”

What is particularly ironic about seeing this production is the extended parallel of censorship then and now but differently processed. Ibsen never imagined media, social media and AI. Instead, of publishing Thomas’ factual report, the town paper is silent about the danger, censoring the report. Today, lies are broadcast on various media platforms including “Truth Social” precisely to extinguish the credibility of facts. The loudness and cacophony of wrong information and falsehoods deafen those willingly, lazily duped into a conspiracy of complacent trust. Those who would not be duped must read extensively to separate truth from lies and silence the cacophony to tease out what is really happening.

Do we laugh or cry? My response to Strong’s impassioned speeches after his beating and vilification was panic laughter and a few tears at the enormity of witnessing the play’s themes which resonated for me as an anti-MAGA who watched Republican truth-tellers like Liz Cheney, the former president’s Republican administration witnesses at the January 6th Commission, Dr. Fauci, former Governor Andrew Cuomo, and a legion of others who stood and still stand for the truth against the fraudulent former president. For their pleas of truth, they, like Strong’s Stockmann, have been symbolically crucified, character assassinated, demeaned, defamed and threatened with death. The dark ironies of this production are drop dead tragicomedy that is nonpareil in today’s theater.

And as such, this production is a warning. The message for me was “not on my watch!”

There are those who deny and punish truth tellers, whether scientists or Cassandras. Indeed, the more the leaders and their followers cry for blood, it would seem that the greater the confirmation that what is being said that inflames them is accurate. The final twist in this magnificent work which Herzog, Gold and the phenomenal actors have made as plain as day, you will have to see for yourself, if you can get a ticket. The conclusion just might involve a rescue by Captain Horster (Alan Trong), keen on Petra, who offers to take Stockmann, Petra and Stockmann’s son to America. Why? It is better there and the citizens are more amenable to hearing the truth. The audience laughter was as bitter as the dark irony inherent in Captain Horster’s innocent comment.

Re-imagining An Enemy of the People, Herzog, Gold and the creative team have delivered a searing, terrifying and at times humorous work that will remain in one’s consciousness long after one leaves the Circle in the Square. From the imaginatively stylized, technically galvanizing and evocative set design by dots, to the superbly thematic lighting design by Isabella Byrd, the period costume design by David Zinn, and Campbell Young Associates hair and wig design, the director’s vision coheres powerfully.

The singing of Norwegian folk ballads throughout is an additional atmospheric element that establishes setting and grounds us in history. Norway is a place that is often presented as more forward thinking than the US, another irony. Human nature is similar everywhere, especially when ignorance can be manipulated for profit and the illusion of prosperity for the poor, which rarely happens. Mikaal Sulaiman’s sound design helps to convey the timber of the music and voices. It might have been interesting to see a translation of their lyrics in the program.

An Enemy of the People is in a 16 week limited engagement that ends June 16. It is two hours with a five minute pause and no intermission. Circle in the Square, 235 West 50th St. between 7th and 8th. See it for its performances, the fine direction and inspired re-imagining. https://anenemyofthepeopleplay.com/

‘The Notebook,’ Poignant, Reverent, Knockout Performances by Maryann Plunkett and Dorian Harewood

Fans who have seen the film or read Nicholas Sparks’ titular novel will not be disappointed with The Notebook on Broadway, currently running at the Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre. With music and lyrics by Ingrid Michaelson and book by Bekah Brunstettter, the musical based on the Sparks’ novel dramatizes the relationship of Noah and Allie using different couples to represent their life stages. With a few changes in the setting from the novel, young and old can appreciate the deeply personal aesthetic and profound expression of fidelity, not often seen, that reveals Allie and Noah’s intimacy and devotion to each other.

Directed by Michael Greif & Schele Williams, The Notebook’s staging is fluid and stylized, happening mostly in remembrances past. It simultaneously layers the key turning points in the stages of Allie’s and Noah’s relationship (teenage years, late twenties). Through vignettes of scenes between the young Allie (Jordan Tyson) and Noah (John Cardoza) and then the middle Allie (Joy Woods) and Noah (Ryan Vasquez), we understand how the couple’s relationship developed.

We are kept in suspense when Allie’s parents disapprove of Noah and they don’t see each other for years, each pursuing their own dreams. We learn what stood in their way to break them up, and discover how they eventually get back together again, despite their differences in background economically and socially.

The musical takes place in the present in a nursing home where Old Noah (the superb Dorian Harewood), lives to stay near his wife Allie (an incredible Maryann Plunkett), who has degenerative Alzheimer’s. If you have not seen the film or read the novel, you are unaware of Noah’s identity and intentions until he meets with his family and they tell him he cannot afford to stay with their mom in the facility to keep her company. He has to let her go. However, their bond transcends even their children. Noah ignores them.

The strength of the musical is in Greif and Williams’ staging that suggests memory and consciousness brought to life by the journal that Noah reads daily to Allie in her room in the extended care facility. Allie wrote the memoir in remembrance of their love. Noah’s promise to read it to her was made, we learn, when she realized she was becoming immersed in the darkness and confusion of early onset Alzheimer’s. She desperately hoped her own words would trigger her consciousness and memory to maintain their powerful love connection.

The musical’s inherent focus on memory and the indeterminate nature of time in human consciousness reveals how love transcends, heals and can make memories as alive as reality. Eventually, the truth can break through, as it does by the conclusion of the musical, when Allie realizes who Noah is and why he is with her every day. If one has had experiences with relatives who have Alzheimer’s, some relate that in the midst of their relatives’ seeming insentience, there are moments of clarity that appear miraculous. How and why this occurs with this unfortunate condition remains a mystery which one day may be solved.

In respectful consideration of Allie’s situation, Brunstetter’s book encapsulates The Notebook from Noah’s perspective. The directors are mindful of how Noah’s memories and Allie’s words stir Allie, Noah and even Fin (Carson Stewart), who at one point picks up the journal and reads a steamy scene that humorously wows him.

Predominately, the directors strive for coherent, symbolic and meaningful interaction between the couples’ vignettes chronicling, not always in order, but thematically, the events expressing Noah and Allie’s eternal bond created before they were married. As Noah dozes in a chair and dreams of the formation of that bond between Young Noah and Young Allie, the actors are situated downstage to the edge of the proscenium, where there is water and a shoreline bathed in Ben Stanton’s beautiful, bluish tinged moonlight. The night scene conveys an atmosphere of romance. The brief dialogue indicates the couple’s youthful naivete and exuberance where anything is possible even their love. Tyson’s Allie says the words no lover wants to hear; she has to “go home” to her parents.

Ironically, these are words Older Allie in the present says to the nurses and to Old Noah, in confusion, as if she’s searching for the comfort she associates with the home she once made with her life’s partner standing before her, who she doesn’t recognize. Plunkett’s Allie, unsettled in the extended care facility, is triggered by a past that nudges just below her consciousness. She tries but fails to remember the house that Noah built just for her. If only she could get back there, she would know where she is in the present and who the old man is who comes to visit every day.

In that first moonlight and romance scene, Young Noah’s response of eternal love is that Young Allie can stay with him forever, to which she playfully agrees. Simplistic, facile teenagers make promises. However, it is the rare relationship and rare individuals who keep promises in a world of lies, canards, fakery, AI, betrayals, and deceit, where “forever” love is expressed to “get over” and treachery and selfishness are the game plan.

The Notebook is profound in its simplicity, and can be underestimated. Indeed, who is able to love forever, be faithful to one person forever, and not just give lip service to a relationship? This is a key theme of the musical, for through Noah’s unwavering fidelity and Allie’s words, we see how this is possible for this couple who loves simply and endearingly. Overall, the production manifests this theme with sincerity aided by the phenomenal performances of Plunkett and Harewood, who pivot the action forward as the Noahs and Allies affirm the beauty of the relationship in snippets of dialogue and the vitality of song.

Young Noah and Allie lightly reference a forever love which indeed comes true; both age together and Old Noah stays with Old Allie to the very end of their lives. Likewise, the promise they make as kids to see each other the next day also comes true in their lives together, even when a gulf of oblivion separates them. Old Noah sees Old Allie in her room to read from the journal in hope every day. Plunkett’s masterful effort in presenting Allie’s struggle to know her identity and Noah’s, paves the way for the payoff at the conclusion, where she remembers, and together they metaphorically return forever to the home they have made of their love.

The music and songs resonate, some more forcefully, some more lyrically than others. The opening song that Harewood’s Noah sings with the ensemble (except for Older Allie), “Time,” is an inspiring and soulful ballad that embraces life’s mutability and time’s swift passage. The song summarizes the permanence of their future relationship and unfolds with the presence of the younger and middle couples who sing with Old Noah symbolizing Allie and Noah’s younger selves.

It is a soundscape of memories where they identify how they live “to keep going, keep running, keep standing, keep leaning, keep learning, keep hoping.” This premiere ballad establishes what’s to follow, as the ensemble’s voices meld with loveliness in lyrical harmonies. This first song, the song at the end of Act I, “Home,” and the final song, “The Coda” are the most powerfully wrought and most memorable and significant in relating the love and devotion of this unique couple who have been blessed in their love and faithfulness.

Throughout Act I Old Noah persists coaxing Old Allie with the journal passages, and we follow the narrative of their first kiss and first intimacy, first fight, first pledge to write to each other. The musical reveals these two are drawn to love on another level, which is the mysterious unseen of love relationships.

This is in contrast to the socially acceptable diagram of “successful love and marriage,” which Allie’s mother (Andrea Burns), wants for her daughter. Allie’s mother defines happiness by the society’s values of career success and college education, which Allie is forced to accept because of her mother’s betrayal for “Allie’s own good.”

However, Allie and Noah’s relationship, unlike Allie’s mother and father’s relationship, is not defined by material things and upward social mobility. Though Brunsetter doesn’t mention “spiritual” vs. “material,” the undercurrents are clear when the excellent Joy Woods’ Middle Allie in her solo numbers affirms who she is and who she wants to be (“Leave the Light On,” “My Days”). To what extent Noah is a part of who she wants to be, she discovers when she returns to the town and is drawn by curiosity and an unconscious, perhaps spiritual desire to locate the house Noah has built and outfitted for her with his superb carpentry and woodworking skills.

In the subsequent scene the invisible bond between them manifests. We discover what prevented them from being together sooner in a powerful scene between Burns’ mother and Woods’ Middle Allie. Instead of belaboring additional details, Brunstetter moves the action to its foreshadowed conclusion. This doesn’t occur before a few suspenseful, gyrating events in flashback and in the present. One is that Old Noah, who is in the hospital after a stroke, won’t be able to keep his promise to rekindle Allie’s memory ever again.

Kudos to the creative team who carried the directors’ visions for The Notebook. These include David Zinn & Brett J. Banakis (scenic design), Paloma Young’s color coordinated costume costume design, Ben Stanton’s lighting design, Nevin Steinberg’s sound design (I could hear every word) and Mia Neal’s Hair & Wig Design. Additional kudos to Carmel Dean’s music supervision and arrangements and Katie Spelman’s choreography.

The Notebook is a must-see because of the performances and the directors’ vision in bringing reality to a popular work of fiction. Ignore the pandering “tear-jerker” comments by some critics for whom fidelity and eternal love may be empty promises.

The Notebook, one intermission runs until November 24th. Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre, 236 West 45th Street between 7th and 8th. https://notebookmusical.com/tickets/

.

‘Pericles’ by Fiasco Theater a Joyful, Redemptive Must-See at CSC

Fiasco Theater’s Pericles presented by CSC is one of William Shakespeare’s works written in the twilight of his career that reveals a “hero” who the fates torment and play with until it is enough, and he receives his wish of a fulfilled life with family. The production directed by Ben Steinfeld is stylized and cleverly wrought, advancing storms, shipwrecks, kidnappings and more with the ingenuity and charm joyfully delivered with as little forced spectacle as possible, yet with an intriguing, bold and seamless minimal set and prop design. Currently at CSC until March 24, this is a must see which Fiasco has brought for us to appreciate.

Steinfeld is Gower, the troubadour whose tale this is. Through his music, lyrics and poetry he sets up the play and requires the audience to use their imagination to become involved with Pericles of Tyre’s harrowing and amazing adventures of a lifetime. Steinfeld’s Gower introduces every section and gives a summation of events essentially cluing in and reminding the audience to stay focused and attentive. He leads the cast in song initially and establishes the mood for each of the acts, making sure to recap the events in rhyme after the audience returns from the 10 minute intermission before Act 2.

There are four actors who portray Pericles and give their timber to each scene and adventure that Pericles experiences as he goes on a hero’s journey learning wisdom, perseverance, patience and fortitude, struggling to overcome whatever Fortune brings.

The first Pericles is Paco Tolson who journeys to the kingdom of Antioch where he must solve a riddle to marry King Antiochus’ (Noah Brody) beautiful daughter (Emily Young). If he doesn’t solve the riddle, he forfeits his life and hangs like the other suitors in the public square which the creative team and actors simplistically yet fearfully stage with staffs and boxes/crates. Hearing the riddle, Pericles shows his brilliance apart from all the suitors who have courted the king’s daughter and died. He understands King Antiochus’ treachery. The riddle infers the king’s incestuous relations with his daughter, who he will never give to a suitor.

Upon realizing this horrid circumstance, Pericles also realizes his own fate. Either way, if he reveals the riddle and exposes the king’s sin to public humiliation or doesn’t, he’s a dead man.

Making his excuses, Pericles ends up escaping Antiochus’ kingdom. He intuits the king will figure out why he left and come after him, so Pericles goes on a journey to Tarsus where King Cleon (Devin E. Haqq) and Dionyza (Titiana Wechsler) make their home and suffer through the dire misery of famine that has struck their lands. Knowing their plight, Pericles brings corn to Tarsus’ starving people and saves them from death. Forever grateful, King Cleon makes Pericles revered and celebrated in the land with friendship and goodness. However, we learn that kings are political and variable and circumstances change to sever the friendship.

For the moment in his life’s travels Pericles is unaware of the possibility of deceit and betrayal. Called back to his home in Tyre by the administrator he left in charge, Helicanus (Paul L Coffey), Pericles once more bares himself to Neptune’s wrath on the fickle Mediterranean where the god upends and destroys his ship. Fiasco Theater’s inventiveness of Pericles braving the storm’s fury (Mextly Couzin’s lighting design and the Fiasco’s production design), using a bolt of cloth to suggest the tempestuous waves, maintains the stylized, roughly-hewn playfulness of the production. The soft, shimmery cloth symbolizing the waves belies the irony of Pericles’ situation on the roiling sea.

Pericles loses everything but his life and is washed up on the shores of Pentapolis. There, he is at the mercy of the fishermen who find him and change his fortune with happy information. Pentapolis is ruled by the goodly King Simonedes, (the humorous Andy Grotelueschen), a pleasant reversal of the kings who have gone before.

Shakespeare contrasts the kingdoms and their kings: the first is a lecherous murderer, the second variable in deceit and this third king. The fun loving Simonedes is popular even to the lowly fishermen who tell Pericles that the king holds a tournament and feast for his daughter’s birthday. The celebration is so that Thaisa (Jessie Austrian) may find suitors among the knights who joust for her. When Pericles’ armor washes ashore, the fishermen encourage him to compete for the king’s daughter. Shakespeare makes it a key point that though he is a stranger (an migrant) in their midst, he receives their country’s hospitality and mirth.

Pericles wins the jousting matches, performed with the sames staves Fiasco used to suggest the suitors’s hanging in Antioch. It is an example of how the theater company employs the props efficiently and meaningfully to emphasize themes of power, leadership and control. Through their variable exchange we note the contrast between the kingdoms and their rulers’ leadership, either deceitfully tyrannical or happily beneficent.

After the tournament, King Simonedes invites all the knights for a feast. The wooden crates which have been used as a throne, to circumscribe walls, etc., are now used to effect a long feast table. And there, Pericles (Titiana Wechsler portrays Pericles in this segment) gains the king’s favor and the love of Thaisa.

For his pains and pleasure, the Simonedes playfully uses reverse psychology to have the couple declare their love to each other by pretending to forbid their union. Jokingly, he reveals his pleasure at their marriage which produces an heir. In the next scene we see that a pregnant Thaisa, and husband Pericles (Noah Brody in this version) go on an ocean voyage back to Tyre to check on his kingdom.

Again, there is a storm at sea and dire circumstances. Thaisa who dies in childbirth must be thrown overboard to steady the ballast or the ship will sink. Pericles prepares her coffin with spices and jewels with a note to whomever finds the coffin to bury his wife whom he greatly loves. The child who was born as Thaisa died Pericles names Marina. To redeem the time, Pericles leaves Marina with those who revere him in the land of Tarsus. King Cleon and Dionyza promise to care for Marina like she is their own, while he returns to rule Tyre.

The staging of the scene where Marina is given to King Cleon is simultaneously juxtaposed with the fate of Thaisa whose coffin washes ashore at Ephesus. The director makes excellent use of the space at CSC to clarify what happens. As Pericles hands over baby Marina to his friends, a woman with powers of healing (Tatiana Wechsler with hair down in flowing priestly robes) restores Thaisa back to life. So thankful is Thaisa that she becomes a devotee of Diana and officiates at her temple. Meanwhile, Pericles is heartbroken and grieves his dead wife but joys that his child is being raised well. As fate would have it, during the fifteen years Marina has been brought up with the daughter of Dionyza, things grow problematic.

Dionyza envies Marina’s beauty and talents and decides she must be murdered for the sake of her own daughter, so their child will shine if the glory of Marina is removed. Though Cleon opposes Dionyza’s evil act, he is powerless to stop her. But just as Marina is about to be killed, pirates kidnap her and thwart the murder. In the following sequences, Gower shifts the mood once more and the riotous humor of how Marina’s chastity is used to great effect proves comical in a brothel run by Bolt (Andy Grotelueschen) and Bawd (Jessie Austrian). There, Emily Young’s Marina turns away the lusty, hot clients who are horrified that she pushes her virginity onto them and attempts to make them Diana (the feminist of the time) devotees. Of course the irony is that Thasia, her mother, is back in Ephesus praying as a Diana devotee.

In the second act, Fiasco’s farcical skills shine and the atmosphere shifts from Fate’s woes to merriment at those lecherous males who should be ridiculed for their unseemliness. However, when it is least expected, Pericles, who returns to Tarsus to bring his daughter back to Tyre to rule with him, discovers through Cleon that Marina drowned. Indeed, King Cleon and his wife have betrayed Pericles’ goodness and there is no punishment for them as there was for King Antiochus who the gods burned up. It would seem that incest is the worst crime when it begets murder. Dionyza’s intention of murder the wicked pirates interrupted; it is an irony is that the pirates evil act is turned around for goodness. Dionyza’s envy and murderous intention the gods leave to her and Cleon’s consciences to seek redemption.

Inconsolable that she is gone, Pericles (an excellent David E. Haqq in the last, most emotional segment) will not speak and is dead in spirit. How events change magically to effect Pericles’ reunion with his wife and daughter is poignant and heart-rending, if not fanciful in hope. Interestingly, Shakespeare makes abundant use of the Deus ex Machina (the gods interrupt evil fate to save the hero) in Pericles. As Gower and the cast conclude the tale of Pericles, King of Tyre, we are uplifted by the grace of a happy ending, and the redemption offered to Marina, Pericles and Thaisa because of their goodness, devotion to the values of truth, generosity, decency and steadfastness.

The strengths of this production include the fine ensemble’s seamless acting which provides the coherence throughout, even though the character of Pericles has four actors which was initially confusing. The whimsical and at times farcical, lighthearted approach toward myth-making and storytelling through music, rhyme, dance and song are superbly balanced throughout. The stylization is the correct choice for a play that gyrates throughout voyage, disaster, and roller coaster storms that metaphorically parallel human joys and sorrows.

That the play has been spurned as silly and not worthy of being produced has been a misread of the depth of one of Shakespeare’s most trenchant latter plays. The life theme is an important one. For those who patiently endure, they gain wisdom in temperance and the power to face and overcome trials of their faith. The obstacles help one all the more appreciate and be grateful for a life that acknowledges human beings live on the brink of peril every moment of their lives. To be numb to that knowledge is to live a zombie death in life.

This is a must-see, for the music, songs, fantasy, laughter and fanciful, profound truth-telling.

Pericles. CSC, 136 E 13th St between Third and Fourth Avenues. Closes March 24th. https://www.classicstage.org/pericles/

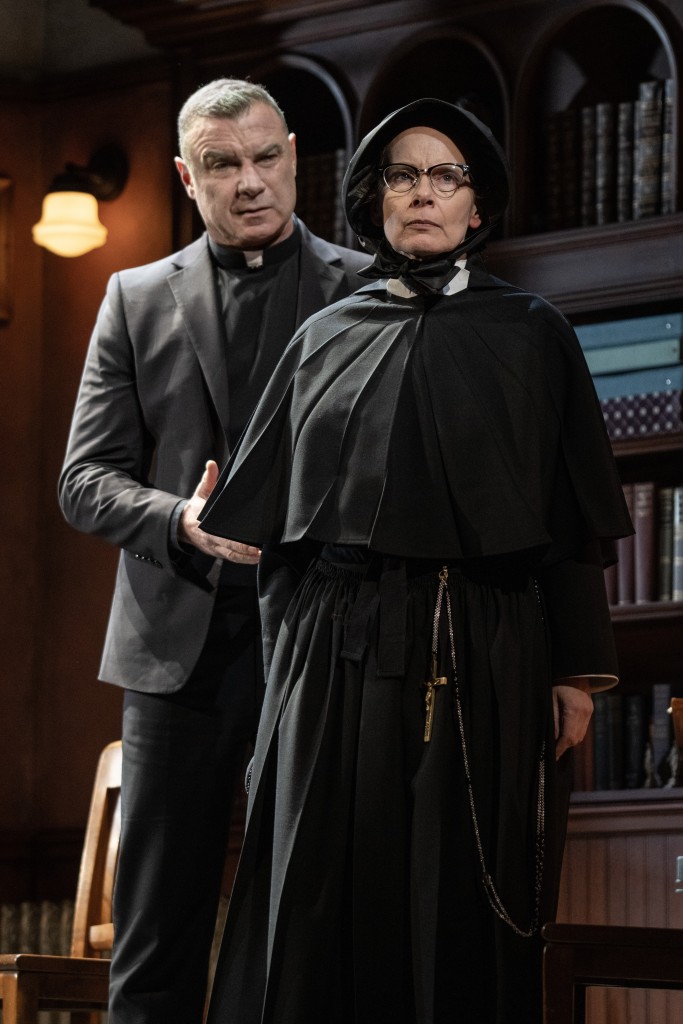

‘Doubt: a Parable’ The Revival With Liev Schreiber and Amy Ryan is Exceptional

If nothing is certain but uncertainty, then “doubt” is a natural state, as genius quantum physicist Werner Heisenberg in his uncertainty principle postulated. However, in the realm of faith, “doubt” may be a blasphemy as scripture encourages Christian adherents to “walk by faith, not by sight,” believing fervently, blindly in God and His truths. Such is the position that Sister Aloysius Beauvier (Amy Ryan) initially presents in John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt: a Parable ably directed with specificity and edginess by Scott Ellis.

Doubt, currently in its first revival on Broadway since it premiered in 2005 continues to be a controversial powerhouse exposing embarrassing infelicities about the Catholic Church and the patriarchy.

In this beautifully acted revival running with no intermission at Todd Haimes Theatre, we note how the play emphasizes many of the divisive cultural issues at stake today though the setting is 1964, the Bronx, New York. However, Shanley nails the timeless sticky problems operating then and now with institutions that are incapable of policing themselves when they are run by men. Specifically, the play delves into church sponsored schools. Their male dominated hierarchy and paternalism shuffled off the harder tasks of teaching, learning and administration to the women. In this instance, the Sisters of Charity do the scut work in “collaboration” with the diocese in the fictional St. Nicholas Church.

To highlight his themes Shanley contrives a situation among three religious adherents who influence children toward or away from Catholic tenets. These include the charismatic Father Flynn (Liev Schreiber), pastor of St. Nicholas, the school principal, Sister Aloysius, and neophyte teacher and nunm Sister James (Zoe Kazan). Their dynamic interplay reveals age-old issues about the best and worst of human nature, goodness, egotism, arrogance, the need to control through guilt and fear, inability to discern lies from truth, gender inequality and hypocrisy.

Doubt opens with Schreiber’s Father Flynn addressing the audience as his congregation, preaching a sermon on the opportunities of having doubt as a part of the bonds of faith. Father Flynn’s sermon frames the play’s arc of development and the subject becomes the driving force as each character confronts their uncertainties about what is right, decent, truthful as they project their own inner weaknesses onto the behavior of each other. Importantly, their uncertainties reveal a crises of their faith in God to move them through the darkness. Instead of allowing God’s love to unify them, darkness, suspicion and doubt overcome them.

The second scene opens on the office finely outfitted by David Rockwell’s wood paneled set design on a turntable which later revolves to show a pleasant Garden and backdrop of the city beyond. Sister Aloysius unleashes her intentions and suspicions on Sister James in the confines of her principal’s office. Ryan’s Sister Aloysius is a martinet who runs a tight ship with a stern, icebox demeanor. In her spot-on, nuanced portrayal of the nun, Ryan never shines forth Christ’s light and love and remains largely an emotionless cipher until the conclusion. To her credit, Ryan never pushes Sister Aloysius’s austere attitude over the edge, but breathes feeling and life into her persuasiveness and her determination with fervency.

On the other hand, Father Flynn (Liev Schreiber) the priest, who is the pastor of St. Nicholas, manifests an openness, intelligence, flexibility, forward thinking personality and sense of irony. He and Sister Aloysius appear to be opposites in character, though both fabricate and lie; Father Flynn to drive home themes in his sermons, Sister Aloysius to “get at” the truth. The lighthearted, yet controlling Father conducts the physical education program and religion at the school. Both Sister Aloysius and Father Flynn follow the hierarchy and answer to the Monseigneur. This remains an obstacle for Sister Aloysius because she deems the elder cleric “other worldly” to a fault. She tells the young neophyte Sister James (Zoe Kazan), that he “doesn’t know who the president of the United States is.” Yet, here men rule.

A problem for the manipulative, coercive Sister Aloysius, the Monseigneur will dismiss any issue she brings to him, unlike another cleric she confided in at St. Boniface who believed her word and got rid of a priest Sister Aloysius implies was a pederast. Suspicious about Father Flynn, and questioning the personal purpose of his sermon about “doubt,” Sister Aloysius picks at Sister James like a feather pecking chicken who dominates hens by pecking them to draw blood because she enjoys its taste.

Preparing her victim for maximum influence, Aloysius criticizes Kazan’s Sister James. She derides her showboating as a teacher, her enthusiasm about her subject, her kindness to the students. She discourages Sister James’ relaxed atmosphere in her classes. After reducing the young nun to tears, she directs the neophyte to be emotionless and watchful about anything untoward. We learn later, as Sister James confides in Father Flynn, that the older nun has stolen her joy about teaching and has contributed to her bad dreams and loss of peace. This irony is not lost on us today, when religion is used as a hammer and sickle to browbeat and slice up the condemned populace to contort their lifestyles to politicized religious tenets popular over 120 years ago.

Sister James becomes the perfect foil for the imperious, commanding Sister Aloysius to manipulate and play upon in the tug of war between Sister Aloysius and Father Flynn. Initially, the “war” appears grounded in a difference in philosophies and life approaches between progressivism vs. conservatism. However, the divisiveness between them takes a sinister turn and explodes as Sister Aloysius gives rise to her suspicions that Father Flynn is grooming Black student Donald Muller for pederasty by giving him alcohol in the sacristy. It is an accusation that is proven only in her imagination.

Sister James is like a deflated ball tossed about in the storm that rages between Sister Aloysius’s determination to expose and evict Father Flynn from the church and Father Flynn’s insistence he is telling the truth and has done nothing wrong. In a climactic scene between them, Flynn’s denials and pleadings with her to count the cost to Donald, him and herself and to amend her convictions and threats because of a lack of proof, go on deaf ears. She has converted herself into the “anointed.” She would make those of the Inquisition proud, except they never would listen to a female.

To complicate the matter Sister Aloysius meets with the Black child’s mother, Mrs. Muller (the superb Quincy Tyler Bernstine). Mrs. Muller expresses that she is thankful Father Flynn has become her child’s protector. If Donald stayed in his previous school, he “would have been killed” by the bullies. Sister Aloysius dismisses Mrs. Muller’s backstory about her son’s beatings by his father for “being that way.” Instead, the principal is self-righteous and gratified that her determination has led to Donald Muller’s being dismissed from the Altar Boys, which Mrs. Muller explains devastated Donald.

Mrs. Muller leaves with the assurance that Donald will be able to finish out the few months left, but Sister Aloysius is not satisfied and won’t be satisfied until Father Flynn has been exposed and kicked out of the priesthood. Because she is the assiduous hunter of her prey, Father Flynn, we become sympathetic to his cause and Sister James’ acceptance that he is innocent of Sister Aloysius’ allegations. However, the Catholic Church since 2000 has been expelling priests for pederasty and has paid great sums of money in damages to men who testified years later to being abused by priests’ sexual predation.

So, Father Flynn may be a pederast and Sister Aloysius may be correct in her “gut instinct” that he is a predator. Enter Werner Heisenberg. Uncertainty reigns without proof and admission of guilt and an act of contrition and repentance which Schreiber’s stalwart, assertive Father Flynn will never yield up.

The performances and direction are uniformly terrific as is Ellis’ pacing and vision which leaves the audience in a breathtaking conclusion and Sister Aloysius upended and overturned in her philosophy and life approach. Thanks to Linda Cho’s appropriate costume design, Kenneth Posner’s lighting design and Mikaal Sulaiman’s sound design, and Charles G. LaPointe’s hair & wig design, Doubt resonates with currency. As mentioned before, David Rockwell’s scenic design, first with a gorgeous cathedral interior setting for St. Nicholas, then with its turntable sets is appropriate for a place of peace which, by contrast, echoes with torment, division and fear.

The complexity of suspicion, accusation and innocence remind us of our time, and of the insistence of liars to demand they are right on little proof when the stakes are high. In the play’s instance careers may be upended, reputations are at stake, and individuals are harmed for the sake of one’s suspicions of imagination. Today, it is no less shattering that lies are the pylons which shore up candidacies to achieve power by any means necessary, even if it means the destruction of nations, citizens, the government. In its timeless themes about assessing truth when the professing upright religious protect liars, fantasists and themselves from accountability, Doubt is a profound must-see.

Doubt. Todd Haimes Theater, 42nd St between 7th and 8th with no intermission until April 21st. roundabouttheatre.org.

Athena Film Festival 2024: ‘Fancy Dance’ Panel

Decolonizing the Film Industry: Indigenous Women’s Voices

Athena Film Festival opened last weekend. The premiere women’s film festival in New York City celebrated its 14th year. In previous years, the amazing festival has had ground-breaking, maverick films and speakers like Gloria Steinem, Dolores Huerta, Eve Ensler and many more. Held at Barnard College, the labs, workshops and screening of cutting edge films proved to be exciting and revelatory in showing the direction of trends in women’s stories. Filmmakers, friends and supporters conducted talk backs and conversations, and experienced events that explored what it means to be a woman today among diverse groups.

Fancy Dance was a film I enjoyed seeing. There was a Talk Back afterward with the director and creatives who worked on and supported the award winning film, released in 2023 and screened in festivals around the country. Directed by Erica Tremblay and written by Erica Tremblay and Miciana Alise, Fancy Dance stars Lily Gladstone who has been nominated for an Oscar and received multiple awards from critics’ associations, film festivals and a SAG and Golden Golden award for her amazing performance in Martin Scorsese’s masterwork, Killers of the Flower Moon.

The panel after the screening of Fancy Dance.

Like Lily Gladstone and Erica Tremblay, many of the creatives who worked on the film were Indigenous woman and men. The story and themes revolve around Lily Gladstone’s character, Jax, a queer indigenous woman, who must confront her sister’s disappearance, while she lives and takes care of Roki (Isabel Delroy-Olson). Together Jax and Roki struggle to hustle money and at the top of the film we note that Jax with Roki as her accomplice steals a vehicle and drives it to a chop shop for a nominal amount of money. Tremblay, eschews political correctness in her portraiture of Jax and Roki who is not above stealing from a convenience store furtively picking and choosing items she likes while Jax picks up some supplies.

The film combines many elements and is a combination mystery, thriller, road trip and ultimately family drama as Jax deals with having to give up care of Roki to her white father and stepmother. The situation becomes problematic when her grandparents refuse to take Roki to the state powwow where Jax has obfuscated that her mom will be because she is a great dancer.