Blog Archives

‘The Comeuppance,’ a Pre-Reunion Reunion of Five Friends and Death, Theater Review

In The Comeuppance by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, directed by Eric Ting, old friends meet for a pre-reunion reunion at the home of Ursula (the superb Britney Bradford), who has organized a party to celebrate before she sends off friends to their twentieth reunion. In an extension of its World Premiere at the Signature Theatre, the comedy with somber, stark elements was extended until July 9th by popular demand.

Jacobs-Jenkins’ (Appropriate, An Octoroon) themes are timely. The ensemble was spot-on authentic and natural. In his two hour play with no intermission millennials admit the consequences of living with unsound decisions made in the less scrupulous years of their youth. Sooner or later, there is a “comeuppance.” One cannot escape the inevitability of oneself and one’s mortality, as Death, who like a sylph inhabits each of the characters, periodically reminds us.

To effect this principle theme of death in life and the transience of all things, Jacobs-Jenkins places thirty-somethings in a backyard with drinks, weed and a loaded, shared past. They once were part of a high school friend group called M.E.R.G.E.: Multi Ethnic Reject Group. Jacobs-Jenkins allows them to go at each other (Emilio’s bitterness is apparent), as they bond over a perceived closeness, which may not have existed after all.

But first, Death introduces himself after slipping into the soul of the protagonist Emilio (Caleb Eberhardt), who has the most difficult time struggling to let the past remain in the past so he can create a better life for himself. As he does with all the characters, Death speaks through Emilio. He warns the audience he is always lurking in omnipotence, with a complete understanding of who human beings are, including the audience members, which he crudely, fearfully reminds us of, once more at the conclusion.

Since last they met, Emilio, Caitlin (Susannah Flood), Paco (Bobby Moreno) and Kristina (Shannon Tyo) have established careers, been to war, gotten married and had kids. Each in their own way has confronted loss, confusion, cultural chaos and most recently COVID-19. We learn that all have been under an emotional siege. Some are sustaining the sociopolitical chaos that Emilio points out better than others, as they either ignore it, reflect upon it, or allow their own lives and difficulties to blot it out of their consideration.

Interestingly, the generous Ursula, whose home, inherited after her grandmother’s death, has been offered up for the celebration, becomes the first to manifest the ravages of millennial time and aging. She has lost her sight in one eye, having contracted diabetes. She tells the others that she is not up to going to the reunion and they may stay as long as they like at her party.

As Emilio, Caitlin and Ursula wait for the others, Emilio’s irritability spills out in humor against Caitlin, whom he once dated in high school. She has married an older man who is a Trumper, which upsets Emilio. Their two children her husband has from a first marriage appear to be doing well: one is finishing college, the other is beginning a career. Thanks to the actors who present their characters with moment, as the characters cath up their lives, the segment never completely falls into tedium. The characters reacquaint as they step into familiarity with Ursula reminding them of M.E.R.G.E codes they used in high school.

During this segment Death manifests a presence in the monologues from Ursula and Caitlin. They heighten their soul revelations and reflect another aspect of their ethos that is not apparent on the surface.

When Kristina, a doctor with “so many kids” arrives bringing her cousin Paco, who once dated Caitlin and treated her badly, the hilarity increases. It is driven to its peak with the characters’ fronting as a means of getting their “land legs” with each other. By this point the drinks and weed have kicked in and Emilio confronts Paco. whom he clearly distrusts and despises. More revelations erupt and we note Paco’s and Kristina’s individual unhappiness. Once again, Death inhabits Kristina and Paco and expresses their soul’s interior.

Throughout the play Jacob-Jenkins contrasts the material realm and the illusory fitted by human delusion that these individuals have “all the time in creation” to live their lives against the immutable truth of life’s impermanence. Speaking with quietude and without passion, Death assures us he “has their number.” He matter-of-factly reminds us that entropy is king. Things fall apart; human bodies, human relationships, all we hold dear is smothered in half-truths and lies, for we die.

Then the limo arrives and with it well-worked confusion. Ursula goes off to the reunion that Emilio never attends. With the door locked against him and all his buddies gone, he sleeps on the porch, a hapless, solitary and alone soul who needs to “get himself together” emotionally, expiate the past and forgive himself for his failings.

When Ursula returns, we learn the extent of the lies of omission as Eberhardt’s Emilio allows the truth to flow and Ursula shares with him what she couldn’t reveal before. Then Death through Emilio takes his final “comeuppance.” While she “sleeps in her mind” he expresses that his target is Ursula in the immediate future. He discusses that how she will end up is exactly as her friend Caitlin fears. Despite Emilio’s offering to marry and take care of her, Ursula puts him off because she has someone. It turns out, it’s another poor decision for both of them.

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins has woven an interesting conceptual piece that is uneven especially in segments where there is too much ancillary discussion by characters. There is an overabundance of unnecessary detail that impede the forward momentum of the dynamic that occurs on the porch of their lives. In these sections, I dropped out. Perhaps wise editing would make the segments more vital and immediate.

Nevertheless, the actors are terrific. They make the most of the unevenness that drives the play toward the characters’ acknowledgement of duality: of experiencing life and watching and reflecting oneself living it in the knowledge that they are mortal.

The difficulty of this duality is dealing with the reality of Death. In the play it is animated through the characters for our benefit. However, in their lives, it is ever-present in the form of gun massacres, the war in Iraq and Afghanistan, political subterfuge and sabotage in January 6th which attempted to signal in the “death” of our democracy. All of these, Death’s cultural possessions, have brought the characters’ millennial generation to the brink, Emilio acknowledges. That and their body’s frailty is their comeuppance, Ursula suggests.

Though each generation has had its cataclysms, it is the millennials “no way out” that Emilio especially confronts while the others seem to ignore it, save Ursula. Unfortunately, our culture doesn’t do death well and entertainment capitalizes on its particularly gruesome features in the proliferation of horror stories and films. Jacobs-Jenkins counters this aspect, making it a homely creation of back porches. And as he reminds us no one “gets out alive,” at least there is humor. We can laugh on our way out of life’s conundrums, miseries toward Death’s grasp.

Look for this play to be produced elsewhere. And check out their website for more information at https://signaturetheatre.org/

Broadway Theater Review (NYC): ‘Bernhardt/Hamlet’ Starring Janet McTeer, a Stunning Portrayal

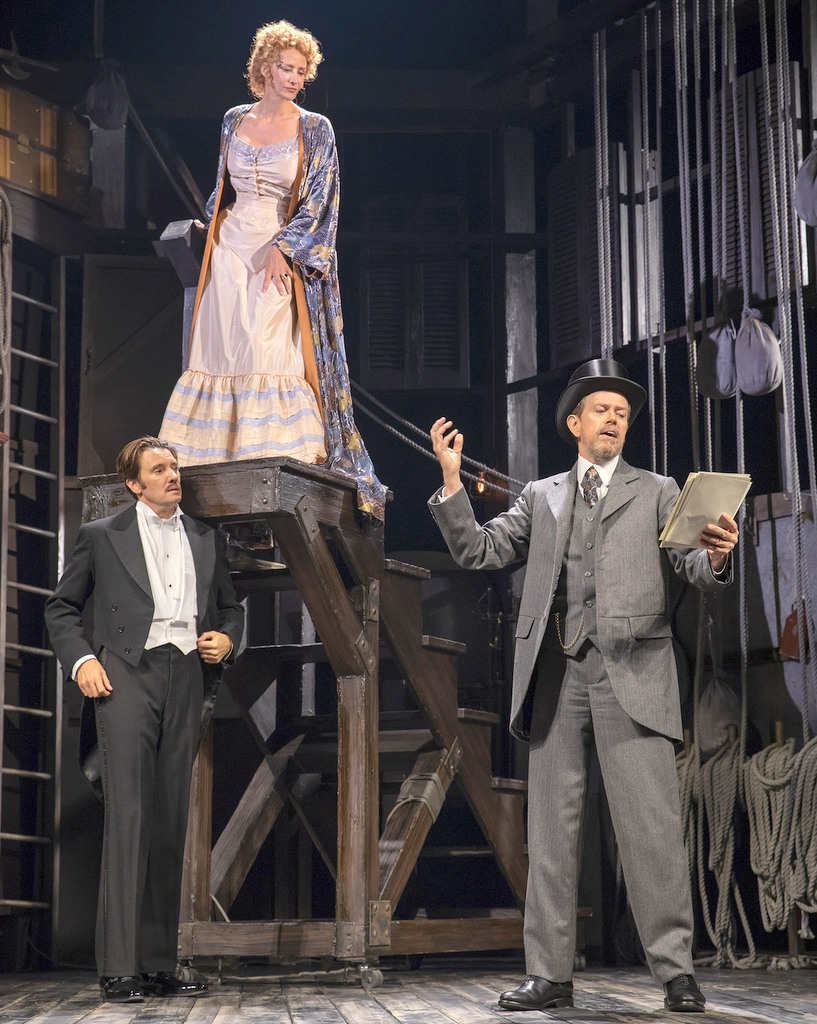

(L to R): Dylan Baker, Jason Butler Harner, Janet McTeer, Matthew Saldivar in ‘Bernhardt/Hamlet’ by Theresa Rebeck, directed by Moritz von Stuelpnagel (Joan Marcus)

Theater scholars, dramatists, and actors are familiar with the legend of French actress Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923), referred to as “The Divine Sarah.” Renowned for her indomitable theatrical greatness, she lived and breathed drama, melding her life and her art so that each informed the other. Alluding to this synergy of living artistry, Theresa Rebeck’s play Bernhardt/Hamlet explores the French actress’s acclaimed reinterpretation of the role of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, which she imbued with her own maverick genius and courage. Examining the actress’s work, the play, thrillingly directed by Moritz von Stuelpnagel, shows us thematic parallels to our times.

As Sarah Bernhardt circa 1897, confronting Shakespeare’s best-known character, Janet McTeer’s dynamism astounds. Her Bernhardt is a whirlwind of delight and shimmering brilliance. She propels the light and dark of human ethos with a range that bounds and swirls and captivates. In short, McTeer infuses her Bernhardt with an infinite variety of emotional hues so that we believe how and why Oscar Wilde referred to her as “the Incomparable One.” Additionally, we appreciate that Bernhardt was not only a visionary in enforcing her will to create opportunities for herself. For women who witnessed her heroism, she drove the platform of freedom, despite and because of a culture and society expressly controlled by men.

Dylan Baker, Janet McTeer in ‘Bernhardt/Hamlet,’ Roundabout Theatre Company (Joan Marcus)

Rebeck intimates that Bernhardt accomplished what every female actress covets. The actress intrepidly portrayed the complexity and angst of Hamlet’s human spirit with the realism of the mysterious feminine gone rogue, as only an exotic like Bernhardt could do. From her affairs with some of the crowned heads of Europe, to her re-imagining herself through her relationships with authors and playwrights, Bernhardt proved her exceptionalism. Continually, as she gained power and fame, she pushed the envelope of female propriety. And amazingly, the public adored her for it.

However, when she takes on the role of Hamlet to bring it to a larger, more profitable theater, her closest allies sound warnings. Edmond Rostand is one such ally. Jason Butler Harner skillfully portrays the poetic, conflicted author of Cyrano de Bergerac, who worked with and wrote for Bernhardt. Her lover in the play (a relationship that was rumor in real life), he must choose between his career and hers. Of course this is an irony. Rarely did women have the opportunity to have choices as Bernhardt did. In this instance, the hard choice becomes Rostand’s with regard to their work on Hamlet.

We see that the two consume each other in their relationship, which is a blessing and a curse. Harner’s potent by-play with McTeer when he challenges her “demented idea” of rewriting the iambic poetry in Hamlet’s speeches is particularly striking. His forcefulness stands against McTeer’s indomitable will in Rebeck’s exceptional characterizations. Their equivalent passion reveals the high stakes for each. Thus we appreciate the inevitability of their partnership taking a turn after he becomes famous with Cyrano and she moves on with an interpretation of Hamlet sans poetic rhythm and written by others.

Jason Butler Harner, Janet McTeer in ‘Bernhardt/Hamlet’ directed by Moritz von Stuelpnagel, written by Theresa Rebeck (Joan Marcus)

The other ally who opposes Bernhardt’s endeavor is critic Louis, played by the stalwart and stentorian Tony Carlin. He argues with and attempts to influence Rostand in an important scene. Here we see the dangerous, shifting ground Bernhardt must negotiate as Louis questions her Hamlet choice. Perhaps the scene could be less expositional, but it is a necessary one for advancing the stakes and presenting the seeds of themes.

For example, women’s stage roles traditionally remained weak asides to fascinating, dominant male protagonists. Male roles, complex and intelligent, provided the driving dynamic that women’s roles did not. To take on a man’s role, a woman must have the power and even greater acumen and ambition to accomplish it well. Unsurprisingly, both men question whether Bernhardt has the chops to meet the Hamlet challenge.

(L to R): Jason Butler Harner, Janet McTeer, Dylan Baker in ‘Bernhardt/Hamlet’ (Joan Marcus)

Through the real-life characters of Rostand and Louis, the playwright highlights the conflicts and problems McTeer’s Bernhardt faces. Additionally, Rebeck shows us how the staging, costuming, and promotion of this new, interpretative Hamlet must be conquered.

Wonderful in supporting roles are Dylan Baker, Matthew Saldivar, and the fine Brittany Bradford as actress Lysette. Baker portrays Constant Coquelin, Bernhardt’s acting contemporary and friend. Notably, Baker gets to have fun playing Hamlet’s father in a hysterical rehearsal scene. Experienced in the role himself, Coquelin guides Bernhardt as a quasi acting coach. Coquelin’s wisdom and sound judgment reflect his greatness as an actor. Eventually, Coquelin took on the role of Cyrano with great success. Baker’s versatility shines in his speeches as Cyrano, Hamlet’s father, and various roles including the great Coquelin himself.

Saldivar portrays Alphonse Mucha, whose artistic skills must beautify Bernhardt’s poster productions. Humorously, he expresses his upset with the task at hand. Indeed, Bernhardt’s hair, her clothing, her stature as Hamlet must enthrall and entice paying customers, a novel feat even for one of his skill. He cannot easily produce advertising artwork that will please Bernhardt, himself, and his public. Thus, as Bernhardt navigates new ground with her incredible decision to play Hamlet, so must Mucha and the others in her circle deal with the “dire” consequences. What a delicious conundrum her “simple” need to play Hamlet creates for these men whom she frustrates yet enthralls!

(L to R): Janet McTeer, Brittany Bradford in ‘Bernhardt/Hamlet’ (Joan Marcus)

The symbolism presented by Bernhardt’s desire to enforce her will upon the culture electrifies. Subtly, when she donned the pants in Hamlet, Bernhardt symbolically freed all women from fashion folkways. Her pants-wearing signals a needed change. Women’s mores were held fast by paternalism and manifested subtly in binding corsets, bustles, and long sleeved-high collared blouses. Worn even in heat waves, these sometimes smothered the wearers, who died of heat prostration. Fashion trends, as painful as they were, laid subservient female stereotypes at women’s feet. And they dared not transgress them. Do such trends abide even today? Sometimes.

In Rebeck’s characterization of Bernhardt, the more restrictive the “thou shalt not,” the more the actress embraced it, conquering fear. In her revolutionary behavior she dismantled the “double standard.” And because she did this with aplomb, sophistication, joie de vivre, and the audacity of wit and whimsy, who could censure her? As she developed her dramatic art, she empowered herself. Memorably, McTeer takes this characterization and with precision lives it in two acts. She evokes the marvelous “Divine Sarah” and makes her a heroine because she can. How McTeer creates her Bernhardt with adroit skill, subtle intelligence and determination is a Bernhardt-like feat.

What a breathtaking reminder of magnificent women in this twisted, political tide of times. Assuredly, Rebeck’s work (McTeer’s speech to this effect rings out beautifully) remains vital and insistent. With commanding power, McTeer’s Bernhardt corrects the historical record, striking forever at the literary and dramatic canon with a tight phrase. She proclaims to Rostand that she will not play the “flower.” The night I saw the production, the women in the audience applauded these words. “I was never a flower, and no matter how much you loved how beautifully I played the ingenue, it was always beneath me. It is beneath all women.”

This moment electrifies. For though women may be compared to flowers, they are not flowers. And Bernhardt, like all women, understands. For women are power brokers, however hidden, however “passive.” Regardless of how much men nullify this truth, “woke” women grew and grow to learn and champion it. And many achieved and achieve momentous feats even from the position of “second.”

Bernhardt captured opportunity and molded destiny so it served her, not the other way around. Strengthening and illuminating her own identity, she wrote her own history, not the one the culture intended to write for her and but couldn’t. McTeer’s inspiring depiction proclaims this with every card in the deck. Indeed, when Bernhardt says about Hamlet, “I do not play him as a woman! I play him as MYSELF,” we glean the full truth of her meaning.

Rebeck wisely selects the most vital of Hamlet’s speeches. Their themes meld aptly with Bernhardt’s conundrums. Indeed, Bernhardt is “a rogue and peasant slave.” At the time she rehearses that speech, she, like Hamlet, divines how an actor uses his skills to portray a character. The double meanings are ironic. But unlike Hamlet, Bernhardt is active, assertive. As Hamlet struggles with acting crazy to hide the knowledge of the truth of his father’s murder, she struggles with a Hamlet too passive to kill. Indeed, the humor comes in watching Bernhardt’s frustration at portraying an “inactive” Hamlet who comes up with philosophical obstacles to delay killing Claudius.

Janet McTeer in ‘Bernhardt/Hamlet’ by Theresa Rebeck, directed by Moritz von Stuelpnagel (Joan Marcus)

Rebeck interweaves in a complex way Hamlet’s speeches to emphasize Bernhardt’s conflict in deciding how to approach and interpret the role. One must work to catch all the ironies. So revisiting the play to enjoy this profound rendering is worthwhile.

Through active dialogue, we learn of Bernhardt’s promotional savvy and ability to reinvent herself for every decade. Naturally, this excites comparisons to today’s long-lasting actresses and others who could learn a thing or two from Bernhardt. Without fear, she capitalizes on rumor, innuendo, and extraordinary behavior that’s verboten for women. Cleverly, she makes critics her friends and generously remembers those who might have turned enemies.

Never an invisible woman, she will play men’s roles. In an affirmation about playing Hamlet and being a woman, she states to Rostand: “Where is his greatness? Where? Is it not in his mind, his soul, his essence? Where is mine? What is it about me you love? Because if in our essence we are the same, why am I otherwise less?”

Thus, Rebeck’s choice of this pivotal, “make or break” moment in Bernhardt’s career is an inspired, complicated one. The turning point reveals the grist, bravery, and revolutionary fervor Bernhardt required of herself to overturn centuries of dramatic tradition. Bernardt’s choice to conquer the greatest role written for men propels her to theatrical heaven. It is sheer artistic genius in a time when women were the “incapable,” “inferior” ones mastered by man’s sham invincibility. Bernardt/Hamlet through the seminal performances of McTeer and the ensemble informs and encourages us to realize that Shakespeare also speaks of women when Hamlet says, “What a piece of work is man. How noble in reason…”

Assuredly, kudos go to the spectacular artistic team. I particularly loved the sets (Beowulf Boritt), costumes (Toni-Leslie James), and hair (wig design by Matthew B. Armentrout). Lighting is by Bradley King and original music and sound design by Fitz Patton.

Bernhardt/Hamlet will be a multiple award winner. It is a must-see TWICE! This Roundabout Theatre Company production runs at the American Airlines Theatre on 42nd Street. The show until 11 November. Visit the Roundabout website for schedule and tickets.