Blog Archives

‘Archduke,’ Patrick Page and Kristine Nielsen are Not to be Missed

What is taught in history books about WWI usually references Gavrilo Princip as the spark that ignited the “war to end all wars.” Princip and his nationalist, anarchic Bosnian Serb fellows, devoted to the cause of freeing Serbia from the Austro-Hungarian empire, did finally assassinate the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess of Austria-Hungary. This occurred after they made mistakes which nearly botched their mission.

What might have happened if they didn’t murder the royals? The conclusion of Rajiv Joseph’s Archduke offers a “What if?” It’s a profound question, not to be underestimated.

In Archduke, Rajiv Joseph (Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo), has fun with this historical moment of the Archduke’s assassination. In fact he turns it on its head. With irony he fictionalizes what some scholars think about a conspiracy. They have suggested that Serbian military officer Dragutin “Apis” Dimitrijevic (portrayed exceptionally by Patrick Page), sanctioned and helped organize the conspiracy behind the assassination. The sardonic comedy Archduke, about how youths become the pawns of elites to exact violence and chaos, currently runs at Roundabout’s Laura Pels Theater until December 21st.

Joseph’s farce propels its characters forward with dark, insinuating flourishes. The playwright re-imagines the backstory leading up to the cataclysmic assassination that changed the map of Europe after the bloodiest war in history up to that time. He mixes facts (names, people, dates, places), with fiction (dialogue, incidents, idiosyncratic characterizations, i.e. Sladjana’s time in the chapel with the young men offering them “cherries”). Indeed, he employs revisionist history to align his meta-theme with our current time. Then, as now, sinister, powerful forces radicalize desperate young men to murder for the sake of political agendas.

In order to convey his ideas Joseph compresses the time of the radicalization for dramatic purposes. Also, he laces the characterizations and events with dark humor, action and sometimes bloodcurdling descriptions of violence.

For example in “Apis'” mesmerizing description of a regicide he committed (June, 1903), for which he was proclaimed a Serbian hero, he acutely describes the act (he disemboweled them). He emphasizes the killing with specificity asking questions of those he mentors to drive the point home, so to speak. Then, Captain Dragutin “Apis” Dimitrijevic dramatically explains that he was shot three times and the bullets were never removed. Page delivers the speech with power, nuance and grit. Just terrific.

Interestingly, the fact that Dimitrijevic took three bullets that were never removed fits with historical references. Page’s anointed “Apis” relates his act of heroism to Gavrilo (the winsome, affecting Jake Berne), Nedeljko (the fiesty Jason Sanchez), and Trifko (the fine Adrien Rolet), to instruct them in bravery. The playwright teases the audience by placing factual clues throughout the play, as if he dares you to look them up.

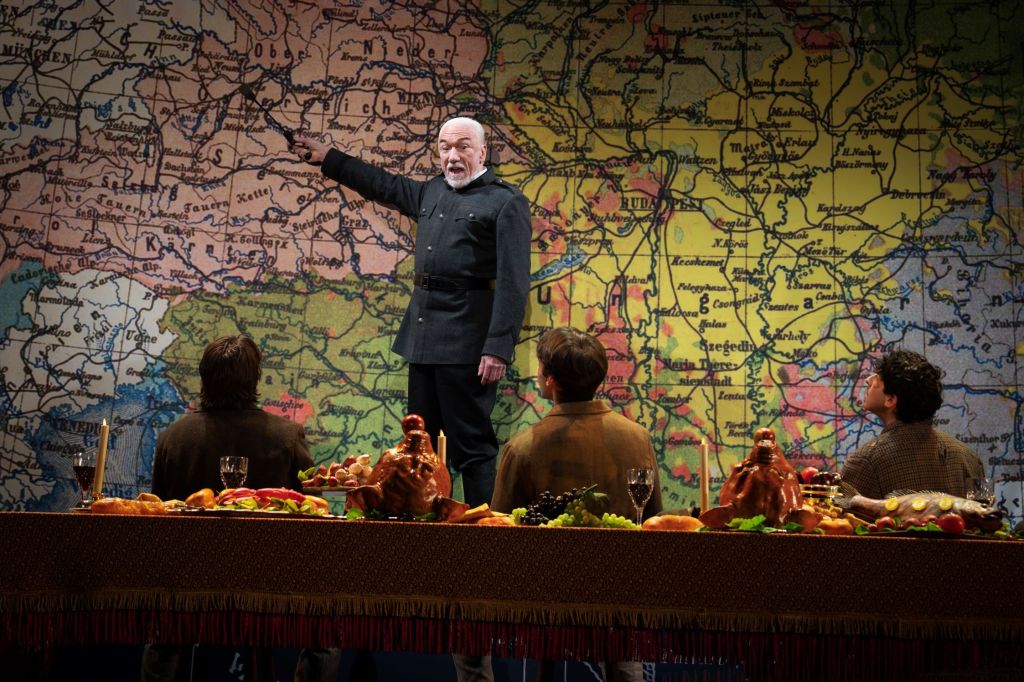

History buffs will be entertained. Those who are indifferent will enjoy the fight sequences and Kristine Nielsen’s slapstick humor and perfect timing. They will listen raptly to Patrick Page’s fervent story and watch his slick manipulations. Director Darko Tresnjak (A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder), shepherds the scenes carefully. The production and all its artistic elements benefit from his coherent vision, his superb pacing and smart staging. Set design is by Alexander Dodge, with Linda Cho’s costume design, Matthew Richards’ lighting design and Jane Shaw’s sound design.

In Joseph’s re-imagining before “Apis” delivers this speech of glory and violence, the Captain has his cook stuff the starving, tubercular, young teens with a sumptuous feast. As they eat, he provides the history lessons using a pointer and an expansive map of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Like brainwashed lap dogs they agree with him when he tells them to. They are inspired by his personal story of glory and riches, and the luxurious surroundings. Notably, they become attuned to his bravery and sacrifice to Serbia, after their bellies are full, having devoured as much as possible.

Why them and how did they get there? Joseph infers the machinations behind the “Apis'” persuasion in Scene 1, which takes place in a warehouse and serves as the linchpin of how young men become the dupes of those like the charming, well-connected Dimitrijevic. From the teens’ conversation we divine that a secret cabal cultivates and entraps desperate, dying young men. Indeed, in real life there was a secret society (The Black Hand), that Captain Dimitrijevic belonged to and that Gavrilo was affiliated with. The playwright ironically hints at these ties when the Captain gives Gavrilo and the others black gloves.

In the warehouse scene the soulful and dynamic interaction between Berne’s Gavrilo and Sanchez’s Nedeljko creates empathy. The fine actors stir our sympathy and interest. We note that the culture and society have forgotten these hapless innocents that are treated like insignificant refuse. As a result they become ready prey to be exploited. The nineteen-year-old orphans have similar backgrounds. Clearly, their poverty, purposelessness, lack of education and hunger bring them to a conspiratorial doctor they learn about because he is free and perhaps can help.

However, he gives them the bad news that they are dying and nothing can be done. As part of the plan, the doctor refers both Gavrilo and Nedeljko to “a guy” in a warehouse for a job or something useful and “meaningful.”

True to the doctor’s word, the abusive Trifko arrives expecting to see more “lungers.” After he shows them a bomb that doesn’t explode when dropped (a possible reference to the misdirected bombing during the initial attempt against the Archduke), Trifko browbeats and lures them to the Captain (“Apis”), with his reference to a “lady cook.”

Why not go? They are starving, and they “have nothing to lose.” The cook, Sladjana, turns out to be the always riotous Kristine Nielsen, who provides a good deal of the humor during the Captain’s history lessons, and the radicalization of the teens, the feast, sweets, and “special boxes” filled with surprises that she brings in and takes out. Nielsen’s antics ground Archduke in farce, and the scenes with her are imminently entertaining as she revels in the ridiculous to audience laughter.

With their needs met and their psychological and emotional manhood stoked to make their names famous, the young men throw off their religious condemnation of suicide and agree to martyr themselves and kill the Archduke to free Serbia. Enjoying the prospects of a train ride and a bed and more food, after a bit of practice, shooting the Archduke and Duchess, with “Apis” and Sladjana pretending to be royalty, they head off to Sarajevo. Since Joseph’s play is revisionist, you will just have to see how and why he spins the ending as he does with the characters imaging their own, “What if?”

The vibrantly sinister, nefarious Dragutin “Apis” Dimitrijevic, who seduces and spins polemic like a magician with convincing prestidigitation, seems relevant in light of the present day’s media propaganda. Whether mainstream, which censors information, fearful of true investigative reporting, or social media, which must be navigated carefully to avoid propaganda bots, both spin their dangerous perspectives. The more needy the individuals emotionally, physically, psychologically, the more amenable they are to propaganda. And the more desperate (consider Luigi Mangione or Shane Tamura or the suspect in the recent shooting of the National Guard in Washington, D.D.), the less they have to lose being a martyr.

Joseph’s point is well taken. In Archduke the teens were abandoned and left to survive as so much flotsam and jetsam in a dying Austro-Hungarian empire. Is his play an underhanded warning? If we don’t take care of our youth, left to their own devices, they will remind us they matter too, and take care of us. Political violence, as Joseph and history reveal, is structured by those most likely to gain. Cui bono? All the more benefit of impunity and immunity if others are persuaded to pull the trigger, cause a riotous coup, release the button, poison, etc., and take the fall for it.

Archduke runs 2 hours with one intermission at Laura Pels Theater through December 21st. roundabouttheatre.org.

‘Smash,’ Fabulous Send up of a Musical Comedy About Marilyn Monroe

Smash

Chatting with two theater critics beforehand, who referenced the 2012 NBC television series also called “Smash,” I was initially distracted. The TV series set in the present revolved around two aspiring actresses who compete for the role of Marilyn Monroe in a Broadway-bound musical called “Bombshell,” about Marilyn Monroe. Apparently, the TV series which devolved into a musical soap opera, lasted two seasons then was cancelled. Since I never saw the series, I tried to ignore the critics’ comments. I fastened my seat belt and settled in to watch the revamped production in its current run at the Imperial Theatre with tickets on sale through January 4, 2026.

I had no reason to”fasten my seat belt.” Smash is a winner. Superbly directed by Susan Stroman, a master of comedic pacing and the quick flip of one-liners, Smash is a resounding must see, retaining little of the TV show with the same title. I adored it and belly-laughed my way through the end of Act I and throughout Act II.

Into the first act when Ivy Lynn (the grand Robyn Hurder), introduces her Method Acting coach, Susan Proctor (the wonderfully funny Kristine Nielsen channeling Actors Studio Paula Strasberg), I embraced the sharp, ironic and often hysterical, theater-referenced send-ups. The book by Bob Martin & Rick Elice is clever and riotous, pushing the true angst of putting on a big Broadway musical and spending millions to make it a success. Martin and Elice’s jokes and the characterizations of Nielsen’s Susan Proctor and director Nigel, the LOL on point Brooks Ashmanskas (The Prom), who tweaks the gay tropes with aplomb, work. Both actors’ portrayals lift the arc of the musical’s development with irresistible comedic riffs shepherded by Stroman’s precise timing.

The music had me at the opening with the vibrant fantasy number, “Let Me Be Your Star,” sung by Robyn Hurder, whose lustrous voice introduces Marilyn and her fandom which the creators attempt to envision with fully costumed performers singing for their musical, “Bombshell,” the Marilyn Monroe story. Then, the scene shifts to the rehearsal room where we meet the creative team who imagined the previous number and scene. Ashmanskas’ director/choreographer Nigel humorously bumps heads with writer/lyricist/composer-husband and wife team Tracy (Krysta Rodriguez) and Jerry (John Behlmann).

Also present, is his associate director and Nigel’s right arm, the golden voiced Chloe (Bella Coppola). She runs interference and puts out fires, even covering for Ivy Lynn and understudy Karen (Caroline Bowman), during an audience invited presentation. Why Ivy Lynn and Karen can’t go on is hysterical.

The music by Marc Shaiman, lyrics by Scott Wittman and Marc Shaiman, and the choreography by Joshua Bergasse are upgraded from the TV series with a curated selection of songs to align with the comedic flourishes. The musical numbers and dances cohere perfectly because the performers rehearse for their show “Bombshell.” With music supervision by Stephen Oremus, an 18-piece orchestra charges the score with vibrant dynamism. Featured are some of Shaiman’s brassiest tunes, orchestrated by Doug Besterman. Lyricist Wittman seals the humor and advances the plot. All provide grist for Bergasse’s choreography. Hurder manages this seamlessly as she sings, breathes heartily and dances while the male dancers whip and flip Ivy as Marilyn around. Of course, all smile with effortless abandon despite their exertions.

Importantly, Martin and Elice’s book sports farcical, riotous moments. These build to a wonderful crescendo by the conclusion. By then we realize we’ve come full circle and have been delighted by this send up of the wild ride these creatives went through to induce the belly-laughing “flop,” we’re standing, cheering and applauding. It’s the perfect ironic twist.

Indeed, once the audience understands the difference in tone from the TV series, largely due to Nielsen’s Proctor (she’s dressed in black mourning {Marilyn?} from head to foot), and Ashmanskas’ Nigel, Smash becomes a runaway train of hilarity. This comedy about unintentionally making a musical flop (unlike the willful intent in The Producers), smartly walks the balance beam by giving the insider’s scoop why “Bombshell” probably never finds a home on Broadway. One of the reasons involves too many chefs trying to make a Michelin starred dish without really understanding how the ingredients meld.

Nielsen’s Proctor dominates Ivy Lynn to the point of transforming the sweet, beloved actress into the “difficult,” “tortured soul” of diva Marilyn. The extremes this conceit reaches is beyond funny and grounded in truth which makes it even more humorous. Without giving too much away, there is a marvelous unity of the book, music and Hurder’s performance encouraged by Nielsen’s Marilyn-obsessed Proctor. We see before our eyes the gradual fulfillment (Proctor’s intention), of “Marilyn,” from superficial, bubbly, sparkly “sex bomb,” to soulful, deep, living woman produced by “the Method.” Of course to accomplish this, the entire production as a comedy is upended. This drives Nigel, Tracy and Jerry into sustained panic mode, exasperation and further LOL behavior especially in their self-soothing coping behaviors.

Furthermore, Producer Anita (Jacqueline B. Arnold), forced to hire Gen Z internet influencer publicist Scott (Nicholas Matos), to get $1 million of the $20 million needed to fund the show, mistakenly allows him to get out of hand, inviting over 100 influencers to Chloe’s serendipitous cover performance. The influencers create tremendous controversy which is what Broadway musical producers usually give their “eye teeth” for. Publicity sells tickets. But this controversy “backfires” and creates such an updraft, even Chloe can’t put the conflagration out. The hullabaloo is uproarious.

The arguments created by the influencers and their followers (in a very funny segment thanks to S. Katy Tucker’s video and projection design), cause huge problems among the actresses and forward momentum of “Bombshell.” Karen, Ivy Lynn’s friend and long time understudy, who has been waiting for a break for six years, watches Chloe become famous overnight for her cover. Diva Ivy Lynn who IS Marilyn is so “over the moon” jealous and threatened, she breaks up her close friendship with Karen and turns on cast and creatives, prompted by Nielsen’s Proctor who keeps up Ivy Lynn’s energy with a weird combination of mysterious white pills and even weirder “Method” tips.

Thus, the musical “Bombshell” becomes exactly what the creatives swore it would never become and someone must be sacrificed. Who stays and who leaves and what happens turns into some of the finest comedy about how not to put on a Broadway flop. Just great!

Smash is too much fun not to see. What makes it a hit are the superb singing, acting and dancing by an expert ensemble, phenomenal direction and the coherence of every element from book to music, to the choreography to the technical aspects. Finally, the show’s nonsensical sensible is brilliant.

Praise goes to those not mentioned before with Beowulf Boritt’s flexible, appropriate set design, Ken Billington’s “smashing” lighting design, Brian Ronan’s sound design, Charles G. LaPointe’s hair and wig design, and John Delude II’s makeup design.

Smash runs 2 hours, 30 minutes, including one intermission at the Imperial Theatre (249 West 45th street). https://smashbroadway.com/

‘Infinite Life’ by Annie Baker, a Review

The premise of award-winning Annie Baker’s play Infinite Life, premiering off-Broadway at Atlantic Theater Company’s Linda Gross Theater, is that pain is the crux of life. Directed by James Macdonald, the production focuses on individuals who deal with pain along a continuum from heart-wrenching emotional angst to stoical virtuousness. Regardless of how they confront their suffering, it is never, ever easy. Indeed, most of the time, the pain endured by the characters we meet in Baker’s play foments a nightmare world of shattering identities, where the characters can’t recognize themselves through the agony.

Baker exemplifies this concept superbly with her characterization of Sofi (Christina Kirk) at various segments throughout her ironic, profound work. Through Sofi’s emotional outbursts and wild, antic, verbal expressions of sexuality, we understand the humiliation and self-loathing that often accompanies the resistance to pain’s annihilation of self, which Sofi and other patients acknowledge.

At the top of the play, Sofi converses with Eileen (Marylouise Burke), who walks very very slowly as she joins Sofi in the resting area where they become acquainted. It is then, we begin to understand where they are and why, when Eileen asks about Sofi’s fasting. Armed with a book she is reading, George Elliot’s Daniel Deronda, (an ironic, related, situational reference), Sofi answers Eileen’s simple questions haltingly, which indicates she may not want her “peace” or privacy disturbed by the talkative, fellow patient.

With just a smidgen of dialogue, Baker introduces elements which arise throughout the play and form the nexus around which Baker invites salient questions about consciousness and the synergy of mind, body, psyche and emotions. Key questions encompass the philosophical conundrum of what the characters must do with and for themselves in this “infinite life” of self, from which there is no escape, and fleeting happiness exists in an unwitting past where there was no physical torment caused by disease.

In a slow, dense, heavy unspooling, Baker introduces us to six characters, five women and one man. The women are dressed in casual workout clothes, loungewear and flowing tops (Ásta Bennie Hostetter’s costumes). These indicate the state of treatment they are in, whether “working it,” seeking comfort or relaxing.

The setting is an unadorned, outdoor space with scruffy, lounge chairs they recline on, bordered by a cheap, latticed, concrete block wall (scenic design by dots). We come to learn this area is the patio or balcony of an alternative healing clinic, that was once a motel. The entire production takes place in this outdoor area that overlooks a parking lot with a bakery wafting aromas of fresh bread from across the street that the characters comment on.

Here, as they “take the air, sun and dark night sky,” the women and man who have various maladies share the unifying, dire reality that they are in terrific pain with illnesses that have no solid cure and will probably reoccur. A variety of upbeat attitudes, modified hopelessness, positivity and stoicism resound through their conversations to distract themselves and each other. The conversations reveal the tip of the iceberg, below which the pain they endure alone, unseen, fills their days and nights.

Admirably, perhaps, these patients look to mitigate and heal seemingly without chemicals (no Oxycontin) or conventional medical methods. Nelson (Pete Simpson), who arrives late to the sunbathing scene, shirtless and attractive, has colon cancer which returned after surgery and mainstream treatment. He opts to try the alternative therapies at the clinic for twenty-four days, he confides to Sofi. He’s determined to follow in the footsteps of a friend who received relief at the clinic.

Sofi graphically shares the type of pain she has that involves her sex organs and has no cure which intrigues Nelson as a weird “come on.” Perhaps it is, but it is also her intriguing and extended cry for help in their scenes toward the play’s end. Likewise, Nelson shares graphic, intimate experiences with his colon blockage that involve tasting his own fecal matter. They share their nightmare world and appear to comfort one another, for a moment in time.

Their scenes together become a high point that intimates the possibility of intimacy but dead ends as far as we see and know. Both characters skirt the edges of hopelessness. Sofi doesn’t think she can make it through what the pain requires of her to sustain, which includes the dissolution of her marriage because of a mistake she made. Nelson implies that if his condition remains static, he will plunge back into radiation treatment and conventional medicine. Both appear hapless, buffeted by the circumstances of their body, beyond which they may or may not ever regain an illusion of control.

Through their journey toward relief, the patients have signed on to be put through their paces. The regimen and therapy that Sofi, Eileen, Elaine (Brenda Pressley), Ginnie (Kristine Nielsen), Yvette (Mia Katigbak) and Nelson have agreed to, require they fast, sleep, rest outdoors, drink concoctions fashioned for their various conditions, do passive activities like read, meditate, pray and, if they wish, rest and commune with each other in the common area, if their will and energy occasion it.

Over the first few days, each woman shares her condition and counsels Sofi, the newest arrival in their midst. For example they discuss that the second and third days are the worst, that after she pukes bile she’ll feel better, and she’ll get past her hunger and grow used to the fasting, etc. Narrating the time passages almost at random, Sofi announces hours or minute differentials before the next conversational scene occurs, as the women continue seamlessly sharing from where they left off hours before. Director James Macdonald’s staging is symbolically passive and static.

The effect is a linear, unceasing continuation as though time is not passing at all, and we are in an ever present present, a side effect of horrific pain. However, Sofi and lighting designer Isabella Byrd’s lighting, which switches from sunlight to darkness, disabuse us that time is standing still for these sufferers. Time marches on and drags them and their pain with it, as Sofi reminds us, though nothing appears to be happening on a material level. On a cellular, spiritual level it may be quite a different story; perhaps there is healing and mitigation though it isn’t readily visible to the naked eye.

As we become more familiar with Baker’s pain managers, we learn they are at various stages of their treatment, and marvel that some, like Yvette, are alive, despite their multiple conditions. Hers are numerous with exotic names along with the medication she lists was given to her during and after her bladder removal, cancers, catheterizations, and chemical poisoning side effects from all the doctors’ interventions.

Interestingly, Yvette is the most stoic and accepting that she will face whatever agony comes her way. The exhaustive list of her illnesses is an affirmation of the human will to “make it through” to the next day, where she will continue to suffer. There is valor in that, as Yvette’s will persists. Sofi is her counterpoint and is desperate and potentially, if things don’t change, suicidal.

The women’s conversation is banal and reminiscent of Samuel Beckett’s plays, which find characters waiting opaquely and uncertainly, though here, Baker defines that the treasure they wait for is healing, an absence of the excruciating terror in their physical bodies. Yet, though we watch and listen to what appears to be stasis, sometimes, the characters in spite of themselves, are humorous and ridiculous.

This is especially so when sexual topics arise and go nowhere useful, and some raw sexual language that Sofi uses unwittingly discomforts Eileen, who is a Christian. For example Mia’s Yvette discusses her second cousin who narrates pornography online for the blind, which prompts a discussion of how it is possible for the blind to react to described sexual acts.

In another segment Ginnie initiates a conversation about a pirate who rapes a young girl who commits suicide. The story is part of a philosophical teaching taken from one of Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh’s books. The provocative question Ginnie asks all to think about concerns the Zen Master’s statement that people are the pirate and the rape victim. The thought that are are capable of equal parts of sadism and masochism spirals into absurd and clever responses in a beautifully paced repartee between Nielsen’s Ginnie and Mia’s Yvette.

Following Baker’s “less is more,” undramatic plot where little appears to happen, director James Macdonald’s vision synchronizes with a minimalist, spare, unremarkable set design (dots design studio) befitting a place of transition, a way station after which patients will move back to their homes to continue healing, seeking treatment or dying. The overall shabbiness of the place, coinciding with the external, static situation of pain endurance, indicates the de-emphasis on the material surroundings. Instead, the focus is on the spiritual, deeper consciousness where the inner healing takes place sight unseen and manifests physically when the characters leave, for they’ve achieved some sort of relief. Perhaps some, but not all. Some are still there and in hell.

The minimalist structure is the receptacle for the weighty philosophical, tinged with metaphysical ideas that the characters express between the arduous moments of waiting. Baker has them burst out with pithy statements universal to us all, reminding us that beneath the ordinary, difficult, daily hours each of us sustains, there is the painful construct that we are dying while we’re living. The glorious part is the absence of pain. Eileen says in a difficult moment of agony, “a minute of this is an infinity.” The unfortunate part is if illness and pain comes, there is the bracing life lesson that sickness reminds the sufferer. It is what Beckett’s character said in Endgame, and a statement he repeated. “You’re on earth. There’s no cure for that.”

Baker is fascinating upon reflection, reading the script. With the live production the dialogue was sounded spottily because of the theater’s acoustics, the unequally distributed sound design and low conversational tones of the actors, during various segments. Audience left remained in stark silence while audience right rippled with responses of laughter, throughout during the production I saw in preview. Pulitzer Prize winner Baker is known for her pauses and silences in the dynamic among the characters, which in this play added gravity and profound undercurrents. However, in the performance, the silences were noticeably from audience left as audience right chuckled in delight.

The lack of audience reaction because of sound design difficulties was obvious. Interior pain is more easily expressed on film with close-ups. In an attempt to express their pain’s trembling terror, some actors chose to moderate their projection downward into quietude. Throughout, Mia Katigbak and Kristine Nielsen could be heard. Marylouise Burke managed to get around the conversational tones with a haspy, raspy voice which carried.

Similarly, the other superb actors were present during their important moments that conveyed the play’s themes. However, the audio was not sustained, as it should have been. Ironically, I noted even the young man seated next to me leaned forward on the edge of his seat, and not because the suspense was overwhelming. He was straining to hear. Apparently, this is not a problem for director James Macdonald, though it was for audience members whose experience was less than stellar, unfortunately, for a play which, after its reading, I found to be exceptional, profound and thought-provoking.

Infinite Life runs at Atlantic Theater Company. It is a co-production with the National Theatre. For tickets visit the Box Office at the Linda Gross Theater on 20th Street between 8th and 9th Avenues. Or go to their website https://web.ovationtix.com/trs/cal/34237?sitePreference=normal

‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ Starring Kristine Nielsen, Aidan Quinn

Aidan Quinn in ‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson at the Signature Theatre (Monique Carboni)

Horton Foote’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Young Man From Atlanta, directed by Michael Wilson currently in revival at The Signature Theatre is one of Foote’s homely plays exploring loss, alienation and quiet reconciliations. Kristine Nielsen stars as demure, sheltered housewife Lily Dale Kidder in an uncharacteristic turn away from the high comedy of Taylor Mac’s Gary (it’s a blossoming). Aidan Quinn is her husband, wholesale grocer Will Kidder whose security and success is upended in the twinkling of an eye by the end of the play’s first scene. With these prototypical characterizations, whose actor portrayals are shepherded with sensitivity by Wilson, Foote treats us to a slice of suburban Americana in a representative middle upper class dynamic as a couple confronts the unspoken and faces the unspeakable with poignancy and primacy to move together into the winter of their lives.

Aidan Quinn, Kristine Nielsen in ‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson at the Signature Theatre (Monique Carboni)

Foote opens the play at Will Kidder’s office where we identify Will’s assurance, ambition and success in his discussions with Tom Jackson (Dan Bittner) his assistant and underling in the company. It is an incredible irony and stroke out of left field that boss Ted Cleveland Jr. (Devon Abner) has appointed Tom to replace Kidder whom he fires because he is, in effect, “over the hill” and unaware of the new trends. However, during Tom’s friendly discussion with Kidder when we learn Will has built a new, expensive house perhaps to keep his wife busy and away from thoughts about their son who drowned, Tom is sanguine about his new position and Kidder’s impending doom. To his face he acts the innocent and only until Ted Cleveland Jr. tells Kidder he is fired and that Tom replaced him does the shock wear off and we realize Tom’s surreptitious nature.

Foote, the actors and Wilson allow us to think the opening is just an expositional scene, when in fact the playwright is laying down tracks to steamroll over his protagonists by its end and throughout the play. Inherent in the first scene we note the main themes of the play and character flaws: secrecy, disconnectedness, dishonesty, underhandedness, blindness, pride, insecurity and wobbly integrity.

(L to R): Aidan Quinn, Dan Bittner,’The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson, Signature Theatre

(Monique Carboni)

Quinn’s Kidder takes the news badly and provokes Cleveland Jr. to waive his three month severance because of his blustery, boastful comments about starting his own company. Quinn is superb in revealing the bombastic as well as quieter moments of the character. Indeed, Kidder’s frustration and annoyance that his life and career are taking a dive into the toilet and his life’s work has been abruptly shortened is portrayed with heartfelt, spot-on authenticity by Quinn.

The themes become magnified in the next scenes. Rather than confide in Lily Dale about his firing the moment he steps in the door, he hides the truth from her and attempts to face the trial of coming up with the money for the house and other expenses alone. Repeatedly, the couple reveal that they have lived “quiet lives of their own desperation” without confiding in each other. The excuse is that they do not want to upset each other, however, in their lies of omission, they upset themselves more and make huge mistakes which increase the pressure under which they live, pressure which results in Will’s deteriorating heart.

Aidan Quinn, Kristine Nielsen, Stephen Payne in ‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson at the Signature Theatre (Monique Carboni)

In the midst of this excitement are phone calls. It’s the young man from Atlanta who was the roommate of their deceased son Bill. Throughout the play, he is unnamed and remains a ghostly presence shading them with possible portents about their son’s life. Indeed, by not giving this momentous presence a name or face (he never materializes) he becomes a symbol of menace, of the lie that destroys quietly, of the deception that kills, of the unrevealed mystery that eats away at one’s soul from inside out. Unless and until Will and Lily Dale together deal with “the young man from Atlanta,” both protagonists will self-destruct. It is how they confront this spectre and what he is that propels the marvelous, tricky development of the play.

It is in the first scene that we are apprised of this “young man” in a phone call to Will’s office. Will refuses to speak to him. We sense there is an occult meaning as he calls again and then must be turned away. Foote keeps his mysterious presence looming in the background. Who is he, what does he want and why does he keep calling? Eventually, the material answers give clues to the play’s deeper meanings.

Kristine Nielsen, Stephen Payne in ‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson at the Signature Theatre (Monique Carboni)

As the conflict progresses and Lily Dale and Will stop speaking to each other we discover clues that Lily Dale and Will reveal almost prying out the truth from themselves for fear that hearing it they will break down. Quinn and Nielsen work together beautifully at the gradual exposure of the light as the dawn breaks in their souls. Fortunately, the light breaks on them at different intervals and doesn’t completely overcome them, though Quinn’s performance yields that Will hangs on the edge of darkness. He may collapse and die on Lily Dale. But Foote’s intention is not more tragedy, it is deliverance in the quiet moments when still, small voices murmur in the dark hours of waiting for the dawn.

Because this couple are there for each other in their weakest moments, we understand that though their marriage has had sustained rough patches through the seasons, the most devastating one being the loss of their son and the occluded reason why he died, they do have each other. And it is to each other by the end of the play, they turn for hope and solace as they accept what they cannot change and not regret too much that they weren’t on top of themselves and their own blindness sooner.

Kristine Nielsen, Stephen Payne in ‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson at the Signature Theatre (Monique Carboni)

Rounding out the characters are Lily Dale’s stepfather Pete Davenport and his grandnephew Carson. As Pete, Stephen Payne gives a fine, humorous and measured portrayal of one who appears to be kindly and steady if not too discerning. Davenport stays with Lily and Will. In a particularly well suited scene that drew great chuckles from an audience who understood and had been there, the couple hits up Pete for money separately then together in an attempt to raise the funds to start Will in his own business. Davenport is cheerful and openhanded, but eventually, the fund raising plot explodes when Will goes to the banks and is refused loans. Left and right doors shut in his face and the money that Lily Dale had in her savings has been mysteriously depleted, though Will appears to have given her everything she needs for the new house.

The mystery of this continues until the truth spurts out from guilty consciences and we discover almost everything that has been hidden. As in life, though, there are some secrets only those who kept them know the answers to. However, it is Carson who unwraps the package of assumptions, lies of omission, hidden secrets and deceptions with his cheerful, unassuming presence which ironically also carries with it a hidden and secret component.

Aidan Quinn in ‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson at the Signature Theatre (Monique Carboni)

Carson (Jon Orsini) appears innocent and charming. But the intrigue and conflict increases when Carson reveals he knew Bill’s roommate, the young man from Atlanta who keeps calling the house and upsetting Will and Lily Dale. Carson identifies negative elements about the lying character of Bill’s roommate. Afterward, continued revelations come fast and furious from Will who discovered he was taking money from Bill. He finally reveals this to Lily Dale to chide her to stay away from the young man. The deceptions, the manipulated lures of Bill’s roommate who Lily Dale sees as a lifeline to her dead son continue, until finally the couple confront what in 1950 Houston, Texas was unmentionable, if unthinkable.

As one who helps Lily Dale eventually get to that confrontation, there is the former housekeeper who took care of Lily Dale when she was younger. The dignified, lovely, elderly, black Etta Doris (Pat Bowie) is ushered into the new home by their efficient housekeeper Clara (Harriet D. Foy). Etta Doris is a symbolic character, and she comes with an ironic reckoning. In her elderly, lame condition she feels an imperative to see Lily Dale. She walks a great length to their new home after the bus can only take her so far. Etta Doris comments on the loveliness of the home, and then expresses her condolences on the loss of Bill whom she remembered when he was a child. It is this connection from the past that has an impact on Lily Dale and it is Etta Doris’ unction of her faith and good will that brings to bear a greater truth on Lily Dale, though it is not immediately apparent.

(L to R): Pat Bowie, Kristine Nielsen, Stephen Payne in ‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson at the Signature Theatre (Monique Carboni)

In including Clara and Etta Doris as a reference to another class that was an integral part of the well being of Houston’s elite, Etta Doris is a loving and authentic individual who does not restrain herself from showing her care and concern for Lily Dale. That it is she that offers Lily Dale a remembered affection from the past is one of the vital breakthroughs in the play. With her quiet, vital being, Etta Doris brings that which strengthens Lily Dale to face the truths that Will confronts her with by the play’s end. In that confrontation, Lily Dale and Will must cling to each other and resolve to live with the hurt and pain of their own imperfections. And they must hope that their shared truth will continue to reconcile them to each other and make them stronger, more loving, connected individuals.

The Young Man From Atlanta thanks to its strong ensemble work and fine direction by Michael Wilson resonates as a play of great humanity and truth that is deserving of its Pulitzer. With Jeff Cowie’s scenic design, Van Broughton Ramsey’s costume design, David Lander’s lighting design and John Gromada’s sound design and original music, Wilson’s vision is realized.

The production will be at the Pershing Square Signature Center until 15 December. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

‘Gary,’ With Nathan Lane, Kristine Nielsen, Julie White, Bringing You Tears in Laughter

Nathan Lane in ‘Gary,’ written by Taylor Mac, directed by George C. Wolf at the Boothe Theatre (Julieta Cervantes)

Gary by Pulitzer Prize finalist for Drama, Taylor Mac and directed by the prodigiously talented George C. Wolfe is WACK! (translation: cosmically brilliant, riotous, sardonic in dark and light) This uproarious “Sequel to Titus Andronicus” (Shakespeare’s first and bloodiest tragedy) is a brutal, intense, intimate play about body parts and indelicate body processes we don’t discuss in polite conversation with The Queen. Rich in themes and characterizations with a clever, twisty plot that surprises, it is also about much more.

To give us a handle in how to approach the mood and tenor of Gary, Carol (the sensational Julie White) comes in front of the once glorious, now shabby curtain and addresses the audience in Shakespeare’s favorite verse, rhyming iambic couplets. As Carol validates the how/why that Titus Androicus deserves a sequel, suddenly she spurts blood from a hole where her throat has been slit during the roiling events of the former play.

The absurdity of her discussion about a sequel that is more craven with gore than the original (while spurting blood) is titanically ironic and bounteously funny! Already, the playwright has set the mood and tenor between the horrific and rambunctious, as Carol’s unsuccessful attempts to stem the red flux poises the audience on a balance beam of tragedy and comedy. If this is the first of the production’s many moments of shock and awesomeness, we’re in for the long and the short of it. Let the rollicking fun begin!

Kristine Nielsen, Nathan Lane in ‘Gary,’ directed by George C. Wolf, written by Taylor Mac (Julieta Cervantes)

Conceivably, after every holocaust of war and massacre, someone has to clean up and set things “straight” again. In her wobbly, blood draining state, Carol brings up the curtain to reveal the debacle of bloodshed at the conclusion of Titus Andronicus. Then she totters off to bleed to death. The mounds and mounds of bodies piled up from the coup are staggering. There is one central mound of bodies to be processed, another pile of processed bodies and another under a sheet. Thanks to Santo Loquasto’s scenic design, everywhere you look there is the attempt to organize rotting flesh in the Roman banquet hall that is a temporary storage place of the dead. These number among them rich and poor, wealthy elites, citizens, officials, soldiers, rulers and others swept up in fierce fighting, civil war, apocalypse. Death does not discriminate.

The feast of death poetically will slide into a feast of celebration, for in a day, the hall will be the site of the new Emperor’s inauguration, another power transition. Into this macabre scene comes Gary (the incredible Nathan Lane who is a riot beyond description) a former clown who juggled live pigeons to little acclaim and no success. Things are looking up for Gary; he has a new job as a servant for the court. But what a job!

Having escaped a near death experience at the executioner’s hand by a lightening stroke of genius, Gary ends up in the hall for he told the executioner he would help tidy up the catastrophe of gore by doing maid service. Little does he realize what cleaning up corpses entails, and when head maid Janice (the magnificent, moment-to-moment Kristine Nielsen) begins to show him, he recoils, reconsiders his choice and redirects his “ingenuity” in a different direction. He will not stay there long; he will rise up and go beyond maid service. He will become a Fool, the wisest of the Emperor’s counsel.

Nathan Lane in ‘Gary,’ directed by George C. Wolf, written by Taylor Mac (Julieta Cervantes)

Meanwhile, Janice must teach loafer Gary the tricks of death’s work in the flesh. Grand experience has inured her to dealing with corpses, for she’s been cleaning up after each of the Roman wars for a long time. And Rome has been battling for decades. As Janice instructs Gary in “cleaning,” her fiendish efficiency at pummeling the gas out of the bodies to extract their farts is Nielsen at her hysterical best. Her antic machinations are real and horrifyingly, and equally LOL humorous, as she drains noxious body fluids showing Gary the difference between siphoning out the blood, and pushing out the poo. Lane’s Gary is priceless in his response to Nielsen’s Janice. The two actors are the perfect counterparts to make us roll in the aisles at their irreverence and seriousness.

From the outset, we understand Mac’s themes of class elitism and domination as the two maids disagree, fight and create their own rank to dominate, even as ridiculous as it is to fight over lead maid and subordinate. From the characters’ quips, jibes, demands, insults and resistances, we learn how beaten down the lower classes are through these prototypical plebeians who are the invisible, the disposable. But then again their disagreement if given latitude may rise to add their corpses to the pile and who then would be left to clean up the mess? The human condition to power over others defies class. There must be something better than this!

Though recovery from his near death experience sent him to a place of hell and damnation with Janice presiding as head monster maid, Gary holds to his enlightened state. He considers; maybe he can save the world and make it better, to stem the tide of wars and bloodshed. His revelation spurs him to attempt to convert Janice to his cause and show her there is something better in life than pumping poo and expelling gas from cadavers.

Julie White in ‘Gary,’ written by Taylor Mac, directed by George C. Wolf (Julieta Cervantes)

But Nielsen’s Janice is an incontrovertible martinet. What’s worse is she’s excellent at her job. She actually takes pride in her efficiency and refuses to revolt against the current social “order” or rise above it. She eschews and belittles Gary’s ambitions. She is insistent about keeping her place at the bottom of the social strata so she can stay alive even if she is a fart expeller. But as Gary questions the “life” she is leading, his presence and argumentative logic wear her down. As she processes the bodies and argues and commands Gary, she erupts with aphorisms and sage comments indicating that perhaps there is a shaking going on in her soul. Perhaps dealing with death has made her wise after all and prone to hope as well.

Carol shocks Gary and Janice joining the scene, having survived bleeding to death in a second near death experience to match Gary’s. She adds to the hilarity by confessing her “sin” that she missed an opportunity to save a life. With distraught fervor, White’s Carol cries out a refrain of her “sin” at pointed moments during the conversation with Janice and Gary. Each time she erupts in a whining cry (no SPOILER ALERT, SEE THE PLAY) she is marvelously, brilliantly funny. And yet, we feel for her and “know” we would not have behaved so cruelly and cowardly as she did. (NOT!) But she, too, can be inspired to change.

White, Lane and Nielsen send up his extraordinary satire on death and the tragedy of the human condition to fear, hate, revenge and murder. And finally, they do what Gary persuades them to, with Janice convinced of the rightness of his enlightened suggestions. The characters create an “artistic coup” and turn the tragedy of humanity (in Titus Andronicus) into an absurd comedy sequel, where the audience laughs at itself and reverses the cycle of hatred, killing and violence.

Nathan Lane, Kristine Nielsen in ‘Gary,’ directed by George C. Wolf, written by Taylor Mac (Julieta Cervantes)

Indeed, Mac and Gary parallel in their intentions, as Gary states in creating his artistic coup, that it’s an “onslaught of ingenuity that’s a transformation of the calamity we got here. A sort of theatrical revenge on the Andronicus revenge.” Thus, this ‘Sequel to Titus Andronicus’ is a comedy bubbling up from a tragedy and the production ends with hope sparked from a clown and mid-wife who had a second chance at life to encourage a maid who was enduring a living death.

Though the pallid, fake, pokey corpses are stripped or dressed as Romans and the setting is in the latter days of the Roman Empire, Mac’s message is clear. This is us! This is now! The more ridiculous-looking and absurd the “cadavers” appear, the more death and war hover in the “unreality” of the piles of staged dummy corpses. In displaying the morbidity of violent effects, the production is precisely pacifist. But it is also a “Fooling.” So…interpret as you will.

Mac, with acute, dark wit creates his new Mac-genre-“Fooling” and reminds us how we “play” with our own mortality and that of others by taking our lives for granted. As invisible as one may feel in light of the culture’s social and political corruptions, there is always hope. There is always something one may do to rise above and use one’s genius to help others. The fact that Gary plans an “artistic revolt” to convert tragedy into comedy suits for our time.

Kristine Nielsen in ‘Gary,’ directed by George C. Wolf, written by Taylor Mac (Julieta Cervantes)

The production rises to the heavens buoyed up by the fabulous talents of acting giants Nielsen, Lane and White shepherded by the superb Wolf. I could write volumes about this work and the humane, sensitive and completely organic performances by Nathan Lane, Kristine Nielsen and Julie White that are “over-the-top” impeccable. I cannot imagine anyone else in their hyper-hilarious, exhaustive, and energetic portrayals.

Wolf and the artistic team display the playwright’s vision and sound the alarm with energetic gusto. Can we luxuriate in continued economic class struggles, power dominations which set up the inequities between the rulers and the ruled? Why must the “inconsequential” and “invisible” under classes continuously put up with what their “betters” have wrought to satisfy their own lusts, while destroying most everyone else and above all themselves in the process? It is a wasted institutional genocide that no one escapes. Are we not better than this? The characters try to prove they are. Bravo to the actors for bringing them to loving life.

This production is profound. Its humor is beyond hysterical, of the type that makes you laugh through your tears, and cry laughing. Its loving stroke will blind you and make you see again. In its irreverence, cataclysmic indifference about the dead, and twitting of the frailties of humanity’s proclivity to murder, exact revenge and make war, it is an indictment of the “upper” classes (the audience is mentioned as part of the court) and vindication of the lower classes who put up with them. In short it is irreverently ingenious. Every arrogant, billionaire narcissist should see this “Fooling.”

Kudos to Santo Loquasto (Scenic Design) Ann Roth (Costume Design) Jules Fisher and Peggy Eisenhauer (Lighting Design) Dan Moses Schreier (Sound Design).

Gary runs without an intermission at the Boothe Theatre (222 West 45th Street) until 4 August. For times and tickets go to the website by CLICKING HERE.

Theater Review (NYC): ‘A Lovely Sunday For Creve Coeur,’ by Tennessee Williams, Starring Kristine Nielsen, Annette O’Toole, Jean Lichty

(L to R): Jean Lichty, Annette O’Toole, Kristine Nielsen, Polly McKie in ‘A Lovely Sunday For Creve Coeur,’ directed by Austin Pendleton (Joan Marcus)

Tennessee Williams dramatized women’s quiet lives of desperation. Indeed, his characterizations ping from the haunting, tragic-comedic melodies of emotion he experienced with his family growing up in St. Louis, Missouri. In A Lovely Sunday For Creve Coeur, directed with measured grace by Austin Pendleton, one of Williams’ last plays receives a sterling, masterful presentation. Assuredly, the excellent ensemble of actors provides the poignant atmospheric intensity.

Currently running at Theatre at St. Clement’s, the production deserves a visit for its adroit performances and direction. Pendleton’s nuanced and gradual unfolding of Williams’ dramatic climax at once captivates with its beauty, delicacy, and plaintiveness. Delivered with a less astute balance in shepherding the actors’ portrayals than Pendleton’s, Williams’ complicated play would not deliver the power and heart-break that this production evokes at the conclusion.

(L to R): Kristine Nielsen, Jean Lichty, ‘A Lovely Sunday For Creve Couer,’ Tennessee Williams, directed by Austin Pendleton (Joan Marcus)

Throughout the play we witness three single women’s wants and desires. A fourth, who becomes a foil for the other three, provides the background theme which motivates them to desperation. Each longs for happiness away from her current day to day lower class existence in depression era St. Louis, Missouri. In order to achieve this happiness, they place their hopes in others to deliver it. Ultimately, the women deceive themselves. Clearly, they set themselves up for disappointment after disappointment.

At the opening we note that maternal, nurturing Bodey (Kristine Nielsen in a superb, layered, and profound rendering), chides Dorothea. With precision Jean Lichty portrays the teacher, a fading Southern belle from Tennessee. Lichty’s somewhat frivolous Dorothea spends her entire morning waiting upon Mr. Ralph Ellis’s phone call. Because Bodey is “deaf” and didn’t hear the phone ring when it did, we become persuaded by Dorothea’s view. Initially we believe her relationship with Ralph remains solidly founded. Meanwhile, Bodey prepares food for a lovely outing at Creve Coeur with her twin brother Buddy, anticipating that Dorothea will join them. She insists she will not, for Ralph Ellis has important information to tell her about their lives together.

Strikingly, we see that neither women really listens to the other as each drives forward to achieve their own goals. Dorothea yearns for Ralph, a principal who associates with the country club set. Because of her recent tryst with him, she anticipates that her charms have overwhelmed him romantically as she has been overwhelmed. The inevitability remains clear for her, though Bodey warns her against these notions.

Bodey’s reaction to Dotty’s relationship with Ellis appears questionable. We wonder at Bodey’s potential jealousy of “their love.” The feminine, sweet, pretty Dorothea surely will leave her and get married, a frightening prospect for Bodey. Indeed, Dotty believes that eventually, Ralph will spirit her into a well positioned marriage away from the squalid, spare lifestyle she leads teaching, and renting from Bodey. For her part Bodey, a spinster devoted to caring for others, least of all herself, has given up on her own prospects of marriage. Instead, she believes that her overweight, reliable, unromantic, hearty twin Buddy would be perfect for Dorothea. And if they married, she would be the dependable aunt who would raise their brood and have a vital purpose in their family life.

(L to R): Jean Lichty, Annette O’Toole, Kristine Nielsen in ‘A Lovely Sunday For Creve Coeur,’ directed by Austin Pendleton (Joan Marcus)

During the course of the play, two other spinsters join into this group of women who appear unloved and unwanted. Miss Gluck, a German neighbor who has lost her mother and who grieves incessantly. Most probably not only does she grieve the close relationship loss. But she probably grieves that she will be alone. Thus, she must give herself her own solace daily. Indeed, how much can Miss Gluck rely on the friendship of her neighbor Bodey with whom she communicates only in German? Polly McKie as the mournful Miss Gluck is humorous and believable. Thematically, the character portends what happens to women who do not marry well economically or congenially, or whose husbands abandon them to loneliness and despair.

Annette O’Toole and Polly McKie in ‘A Lovely Sunday For Creve Coeur,’ directed by Austin Pendleton, written by Tennessee Williams, La Femme Theatre Productions (Joan Marcus)

Helena is the fourth spinster who intrudes into the lives of Bodey and Dotty. During the course of her visit, she suggests the monstrous end which awaits the unfortunate Miss Gluck. Incisively portrayed by Annette O’Toole, Helena represents the cruel and bitter archetype of the most miserable of the spinsters. These yearn to escape themselves and falling short, grow venomous and predatory toward other women. Arrogant, acerbic, biting she manipulates with sarcasm. And she bullies and demeans Bodey and Dotty with female cultural mores and the pretense of good breeding. In irony she implies that unless Dotty takes actions to lift herself into an upscale arrangement with her, she will fall into the same despair as Bodey. And with finality, poor Dotty will eventually become a social anathema, the greying, unwanted, depressive Miss Gluck.

As the day unfolds, we learn Helena, too, has wants. A fellow teacher in the same school, she intends for Dotty to be her roommate and share the expensive rent and utilities. Her concern for Dotty’s life path concludes with self-dealing. Her own. She covets the monthly expenses Dotty will hand to her. And she intends Dotty to partner up at their bridge games twice a week for companionship. When Dotty inquires whether the bridge will be mixed, we see the fullness of Dotty’s fear anguish of discouragement.

For Dotty, there is no hope without a man. She cannot define herself in any other terms. Nor can she settle for a kind of contentment or resignation as Bodey, Helena and even Miss Gluck have. For her it’s a man, or it’s the abyss. That her designs fall upon Ralph Ellis and certainly not the overweight, unappealing Buddy, who accompanies his sister to Creve Coeur, is her tragic misfortune.

Tennessee Williams’ ironies and humor seek a fine level in this satisfying and heartfelt production. Notably, the Rolling Stones anthem to humanity rings out loudly in this play’s themes of disappointment and finding one’s courage to move past despair. No, “You Can’t Always Get What You Want!” However, for some of the characters, especially the ones who nurture and look out for each other, they do “get what they need.” Perhaps. Indeed, they may even enjoy a lovely Sunday at Creve Coeur.

Kudos to the artistic team Harry Feiner (Scenic & Lighting Design), Beth Goldenberg (Costumes), Ryan Rumery (Sound Design & Original Music), and the other artists.

A Lovely Sunday For Creve Coeur presented by La Femme Theatre Productions runs without an intermission at Theatre at St. Clement’s (423 West 46th St) until 21 October. Interestingly, the theater was founded by Tennessee William’s cousin Reverend Sidney Lanier. You may purchase tickets at LaFemmeTheatreProductions.org.