Blog Archives

‘Liberation’ Transfers to Broadway Solidifying its Excellence

Bess Wohl’s Liberation directed by Whitey White in its transfer to Broadway’s James Earl Jones Theater until January 11th doesn’t add references to the 2024 election nor the disastrous aftermath. However, the production is more striking than ever in light of current events. It reaffirms how far we must go and what subtle influences may continue to derail the ratified ERA (Equal Rights Amendment) from becoming settled law.

To draw parallels between the women’s movement then and now, Wohl highlights the “liberation” of the main character/narrator Lizzie, an everywoman, with whom we delightfully identify. With Lizzie (the superb Susannah Flood) we travel along a humorous journey of memory and self-reflection as she evaluates her relationship to her activist mom, who gathered with a community of women in Ohio, 1970 to “change the world and themselves.”

Wohl’s unreliable, funny narrator, directs the action and also is a part of it. The playwright’s smart selection of Lizzie as a device, the way in to tell this elucidating story about women evolving their attitudes, captures our interest because it is immediate. Her understanding is ours, her revelations are ours, her “liberation” is also ours. Lizzie shifts back and forth in time from the present to 1970-73, and back to the present. One of the questions she explores concerns why the women’s movement cascaded into the failures of the present?

Assuming the role of her mother, Lizzie enacts how her mom established a consciousness-raising group. Such groups trended throughout the country to establish community and encourage women’s empowerment. Six women regularly meet in the basement basketball court at the local rec center which serves as the set throughout Liberation, thanks to David Zinn’s finely wrought stage design. The group, perfectly dressed in period appropriate costumes by Qween Jean, includes a Black woman, Celeste (Krisolyn Lloyd), and the older, married Margie (Betsy Aidem).

Having verified stories with her mom (now deceased), and the still-living members of the group, Lizzie imagines after introductions that the women expansively acknowledge their hope to change society and stand up to the patriarchy. As weeks pass they clarify their own personal obstacles and their long, bumpy road to change, with ironic surprises and setbacks.

For example, Margie voices her deeper feelings about being a slavish housewife and mother. After months of prodding, her husband actually does the dishes, a “female” chore. Margie realizes not only does she complete housework faster and better than he, but her role as housewife and nurturer satisfies, comforts and makes her happy. Betsy Aidem is superb as the humorous older member, who introduces herself by announcing she joined, so she wouldn’t stab her retired husband to death.

Some members, like Sicilian-accented Isidora (Irene Sofia Lucio), and Lloyd’s Celeste, belonged to other activist groups (e.g. SNCC). Circumstances brought them to Ohio. Isidora’s green-card marriage needs six more months and a no-fault divorce, not possible in Ohio. Celeste, a New Yorker, has moved to the Midwest to take care of her sickly mom. The role of caretaker, dumped on her by uncaring siblings, tries her patience and stresses her out. Expressing her feelings in the group strengthens her.

Susan (Adina Verson) is an activist burnt out on “women’s liberation.” Frustrated, Susan has nothing to say beyond “women are human beings.” She avers that if men don’t treat women with equality and respect, then women’s activism is like “shitting in the wind.”

Lizzie and Dora (Audrey Corsa) discuss how they suffer discrimination at their jobs. Despite her skill and knowledge Lizzie’s editor demeans her with “female” assignments (weddings, obituaries). Dora’s boss promotes men less qualified and experienced than Dora. Through inference, the playwright reminds us of women’s lack of substantial progress in the work force. Very few women break through “glass ceilings” to become CEOs or achieve equal pay.

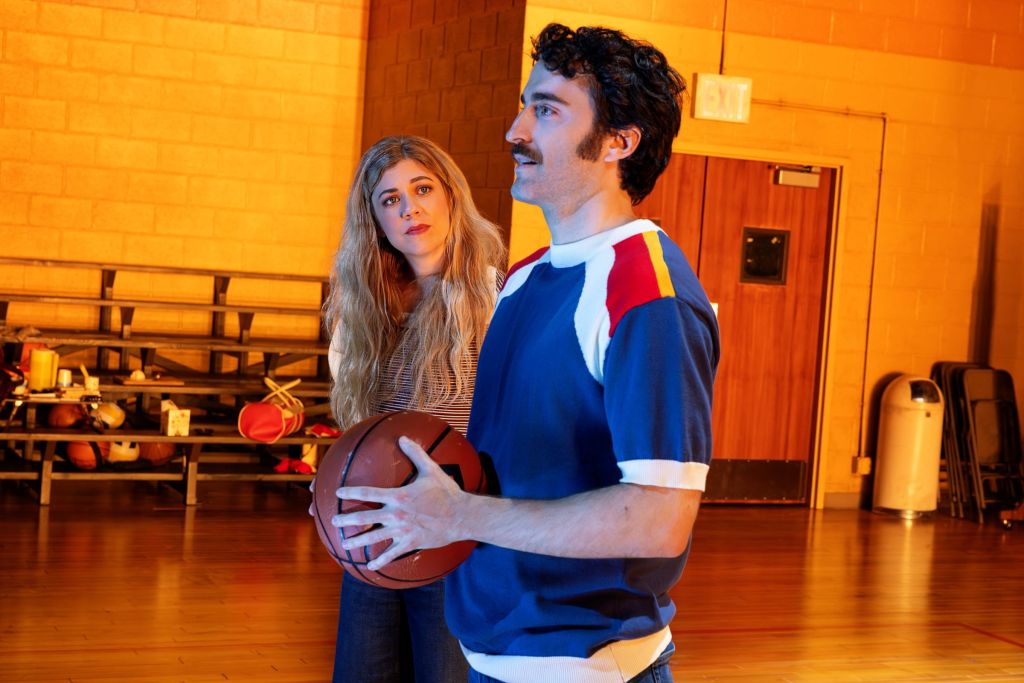

Act I engages because of the authentic performances and various clarifications. For example, Black women have a doubly difficult time at overturning the patriarchy. Surprisingly, at the end of the act a man invades their space and begins shooting hoops. Is this cognitive dissonance on Lizzie’s part for including him? Have women so internalized male superiority that they become misdirected back to the societal default position of subservience? Is this what thwarted the movement?

When Lizzie refers to the guy as Bill, her father (Charlie Thurston), we get the irony. How “freeing” that her mom meets her dad as she advocates for liberation from male domination, only to be dominated by an institution (marriage) constructed precisely for that purpose.

Act II opens with additional dissonance. To extricate themselves from the psychological trauma of men’s objectification of their bodies, the women free themselves from their clothes. Sitting in the nude, each discusses what they like and dislike about their bodies. The scene enlivened heterosexual men in the audience, an ironic reinforcement of objectification. We understand that these activists try to overcome body shame that our commercial culture and men use to manipulate women against themselves and each other (surgical enhancements, fillers, face lifts, etc.). On the other hand the scene leaves a whiff of “gimmick” in the air, though Whitney White directs it cleverly.

After the nude scene Lizzie reimagines how her mom and Bill fell in love. To avoid discomfort in “being” with her father, she engages Joanne (Kayla Davion), a mother who drops into the rec room looking for her kids’ backpacks. Through Bill and Joanne’s interaction, we note the relationship that Lizzie keeps secret. When Lizzie finally reveals she is engaged, the dam bursts and each of the women reveals how they have been compromising their staunch feminist position. One even admits to voting for Nixon with a barrage of lame excuses.

This scene is a turning point that Lizzie uses to explore how women in the movement may have sabotaged themselves at advancing their rights. Reviewing her mother’s choice to get married and co-exist as a feminist and wife, Lizzie reimagines a conversation with her deceased mother played by Aidem’s Margie in an effecting performance. When Lizzie asks about her mom’s happiness, Margie kindly states that Lizzie has gotten much of her story wrong.

Lizzie condemns feminism’s failures. This is the patriarchy, internalized by Lizzie, speaking through her. With clarity through Margie’s perspective, Wohl reminds us that all the stages of the feminist movement have brought successes we must remember to acknowledge.

Lizzie realizes the answer to whether one might be “liberated” and fall in love and “live equitably” within an institution which consigns women to compromise their autonomy. It depends upon each individual to make her own way. Her investigation about her mother’s consciousness-raising group establishes the first steps along a journey toward “liberation,” that she and the others will continue for the rest of their lives.

Liberation runs 2 hours, 30 minutes with one intermission at the James Earl Jones Theater through Jan. 11th. liberationbway.com

‘Saturday Church’: The Vibrant, Hot Musical Extends Until October 24th

With music and songs by Grammy-nominated pop star Sia and additional music by Grammy-winning DJ and producer, Honey Dijon, Saturday Church soars in its ambitions to be Broadway bound. The excitement and joy are bountiful. The music and songs, a combination of house, pop, gospel spun into electrifying arrangements by Jason Michael Webb and Luke Solomon, also responsible for music supervision, orchestrations and arrangements, become the glory of this musical. Finally, the emotional poignance and heartfelt questions about acceptance, identity and self-love run to every human being, regardless of their orientation and select gender identity (65-68 descriptors that one might choose from).

Currently running at New York Theatre Workshop Saturday Church extends once more until October 24th. If you like rocking with Sia’s music, like Darrell Grand and Moultrie’s choreography and Qween Jean’s vibrant, glittering costumes, you’ll have a blast. The spectacle is ballroom fabulous. As J. Harrison Ghee’s Black Jesus master of ceremonies says at the conclusion, “It’s a Queen thing.”

However, some of the narrative revisits old ground and is tired. Additionally, the music doesn’t spring organically from the characters’ emotions. Sometimes it feels imposed upon their stories. Perhaps a few songs might have been trimmed. The musical, as enjoyable as it is, runs long.

Because of the acute direction by Whitney White (Jaja’s African Hair Braiding), the actors’ performances are captivating and on target. Easily, one becomes caught up in the pageantry, choreography and humor which help to mitigate the predictable story-line and irregularly integrated songs in the narrative.

Conceived for the stage and based on the Spring Pictures movie written and directed by Damon Cardasis, with book and additional lyrics by Damon Cardasis and James Ijames, Saturday Church focuses on Ulysses’ journey toward self-love. Ulysses (the golden Bryson Battle), lost his father recently. This forces his mother to work overtime. Unfortunately, her work schedule as a nurse doesn’t allow Amara (Kristolyn Lloyd) to see her son regularly.

Though the prickly Aunt Rose (the exceptional Joaquina Kalukango), stands in the gap as a parental figure, the grieving teenager can’t confide in her. Even though he lives in New York City, one of the most nonjudgmental cities on the planet, with its myriad types of people from different races, creeds and gender identities, Ulysses’ feels isolated and unconnected.

His problem arises from Aunt Rose and Pastor Lewis (J. Harrison Ghee). Ghee also does double duty as the master of ceremonies, the fantastic Black Jesus. Though Ulysses loves expressing himself in song with his exceptional vocal instrument, Aunt Rose and Pastor Lewis prevent him from joining the choir until he “calms down.” In effect, they negate his person hood.

Negotiating their criticisms, Ulysses tries to develop his faith at St. Matthew’s Church. However, Pastor Lewis and Aunt Rose steal his peace. As pillars of the church both dislike his flamboyance. They find his effeminacy and what it suggests offensive. At this juncture with no guidance, Ulysses doesn’t understand, nor can he admit that he is gay. Besides, why would he? For the pastor, his aunt and mother, the tenets of their religion prohibit L.G.B.T.Q Christianity, leaving him out in the cold.

During a subway ride home, Ulysses meets Raymond (the excellent Jackson Kanawha Perry). Raymond invites Ulysses to Saturday Church and discusses how the sanctuary runs an L.G.B.T.Q. program. With trepidation Ulysses says, “I’m not like that.” Raymond’s humorous reply brings audience laughter, “Oh, you still figuring things out.” Encouraging Ulysses, Raymond suggests that whatever his persuasion is, Saturday Church is a place where different gender identities find acceptance.

Inspired by the real-life St. Luke in the Fields Church in Manhattan’s West Village, Saturday Church provides a safe environment where Christianity flourishes for all. When Ulysses visits to scout out Raymond, with whom he feels an attachment, the motherly program leader Ebony (B Noel Thomas), and her riotous and talented assistants Dijon (Caleb Quezon) and Heaven (Anania), adopt Ulysses into their family. In a side plot Ebony’s loss of a partner, overwork with running activities for the church with little help, and life stresses bring her to a crisis point which dissolves conveniently by the conclusion.

The book writers attempt to draw parallels between Ulysses’ family and Ebony which remain undeveloped. As a wonderful character unto herself, the subplot might not be necessary.

As Ulysses enjoys his new found persona and develops his relationship with Raymond, his conflicts increase with his mother and aunt. From Raymond he learns the trauma of turning tricks to survive after family rejection. Also, Ulysses personally experiences physical and sexual assault. Finally, he understands that for some, suicide provides a viable choice to end the misery and torment of a queer lifestyle without the safety net of Saturday Church.

But all’s well that ends well. J. Harrison Ghee’s uplifting and humorous Black Jesus redirects Ulysses and effects a miraculous bringing together of the alienated to a more inclusive family of Christ. And as in a cotillion or debutante ball, Ulysses makes his debut. He appears in Qween Jean’s extraordinary white gown for a shining ballroom scene, partnering with Raymond dressed in a white tux. As the two churches come together, and each of the principal’s struts their stuff in beautiful array, Ghee’s Jesus shows love’s answer.

In these treacherous times the message and themes of Saturday Church affirm more than ever the necessity of unity over division, and flexibility in understanding the other person’s viewpoint. With its humor, great good will, musical freedom and prodigious creative talent, Saturday Church presents the message of Christ’s love and truth against a pulsating backdrop of frolic with a point.

Saturday Church runs with one fifteen minute intermission at New York Theatre Workshop until October 24th. https://www.nytw.org/show/saturday-church/?gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=22911892225

‘Little Women,’ Kate Hamill’s Riveting Update of Louisa May Alcott’s Feminist Classic

(L to R): Paola Sanchez Abreu, Ellen Harvey, John Lenartz, Kate Hamill, Kristolyn Lloyd, Nate Mann in Primary Stages production of Kate Hamill’s adaption of Louisa May Alcott’s ‘Little Women’ (James Leynse)

Oh the tragedy of being a brilliant woman out of her time and place who must, with probity, slip into “becoming” without making too many waves! Kate Hamill’s profound update of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women is presented by Primary Stages at The Cherry Lane Theatre as a two act comedy/drama that reveals how the March sisters adapt or transform the gender roles that the culture dictates for them. The play focuses on Alcott’s view of women during the Civil War when hardship was plentiful and economic pressures were acutely felt by families such as the financially strapped Marches.

Hamill’s update speaks with currency for our time revitalizing the novel with forward-thinking elements as it highlights the 4 sisters and draws comparisons between and among them. Interestingly, Hamill develops their personalities revisiting Alcott’s plot structure and character foundation. But her characterizations gain breadth when she teases out themes and traits relevant to woman today.

The play parallels the salient turn of events in the novel and examines the “little women” as they age into their own perceptions of “womanhood” with regard to the role limitations afforded to women when the only careers available to them were as governesses, caretakers, wives and mothers. Women could not vote, were considered mental inferiors to men who could have them committed to an asylum if they “got out of line.” As wives they were men’s property, chattel to do with them as they pleased, command them as they would under the law. Fortunate are the Marches whose father is an abolitionist and a pastor who is loving toward his wife and children and does not batter them.

(L to R): Ellen Harvey, Kate Hamill, Kristolyn Lloyd, in Primary Stages production of Kate Hamill’s adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s ‘Little Women’ (James Leynse)

In Hamill’s reconfiguration there is an understanding of each of the sisters with an eye on the present. The play’s development concerns how Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy adopt the roles that they will choose and perhaps inhabit for life. In this Hamill has extracted key concepts and fleshed them out to examine the underlying threads of what Alcott inferred but could not write about extensively in order to negotiate the accepted folkways and mores of her culture at the time.

The playwright highlights Beth (a heartfelt performance by Paola Sanchez Abreu) as the spiritual one whose physical weakness and confrontation with the death of the Hummel baby impact her understanding of life’s mutability. As Jo (Kristolyn Lloyd) dubs her “the conscience.” Beth is the one who speaks truth to power quietly, solidly, steadfastly. Bravely, she alone visits Mr. Laurence (John Lenartz) and softens his heart toward allowing Laurie (Nate Mann) to become a part of their family. Wisely, she soothes Laurie’s wounds when Joe spurns his marriage offer. Insistently, she encourages Jo to write from her heart’s core, not from fantastic plots that glorify the male gender and make women into weak creatures. She reconciles the family during quarrels, especially the final explosive argument between the two most antithetical women in the family, Jo and Amy (Carmen Zilles).

In her adaptation Hamill enhances Beth’s wisdom and beauty and highlights the strength of her soul. This is a wonderful teasing out of the characteristics of who she is, the first to be herself and eschew female “type” changing for no one, not even Jo who changes for her. That all the family accept Beth, even Amy, clearly emphasizes her dominion.

The costume design by Valerie Therese Bart superbly reflects each of the characters as Hamill has drawn them. Jo is forever in pants; in polite company, she wears a skirt over her pants. Beth doesn’t wear the outfits the others wear. She is more soul and spirit and thus, she wears invalid gowns of her physical weakness throughout the play. Of all the sisters Beth is perhaps the most actualized. She has “become” before our eyes and thus, is the strong woman which we might take for granted as weak or inconsequential.

Following Hamill’s characterization and apt direction by Sarna Lapine, Abreu’s Beth is subtle strength and quiet wisdom. Yet, she is vibrant and determined when she needs to be in Act II, forcefully chiding Jo (the vibrant, exquisite Kristolyn Lloyd) to shake off self-pity and stir herself to her life’s work as a mature writer with a unique, personal style. She is the sister that is “the rock,” not Jo who is a performer, writer, actor, but mush within, less “together” than the Jo of the novel. This is especially so when her novel is rejected and Beth gives her the resolve and courage to persist and write about what she knows best, the wonderful memories of her family.

The characterization of Meg enacted with with precision and humor by Kate Hamill who portrays Meg, provides the view of womanhood as poised perfection, feminine and graceful. She is the “perfect lady.” Indeed, Meg’s putting on airs at the dance and reminding a bored Jo by coughing to alert her to correct her unlady-like behavior is one of the hysterical highpoints of the production. But her poise at the dance is shattered when she takes off her glasses and becomes dislocated, having to be led around by Brooks (Michael Crane) Laurie’s tutor whom she eventually marries.

(L to R): Nate Mann, Kate Hamill, Kristolyn Lloyd, Primary Stages production of Kate Hamill’s adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s ‘Little Women’ (James Leynse)

The irony of having to be led around by a man because of her myopia is symbolic of what ails women who too easily swallow the culture’s gender roles. Meg has proudly fit herself into the wifely mold until she collapses hammered by the reality of the role’s oppression in a superbly portrayed scene by Hamill, Crane and Lloyd. Meg leaves Brooks and returns home, confiding to Jo her desperation because she is overcome by the impossible reality of domestic life, motherhood and male expectations that the household be run in perfect order every day.

Hamill’s “freak-out” as Meg is both humorous and dramatic. Her fine performance of the scene first with Jo and then with Brooks who is contrite and apologetic, strikes like lightening. Meg goes back to him after she has asserted what she will and won’t put up with and we sense he is a reasonable man; thus, the development of a relationship that is the hope of a partnership of give and take forms. Michael Crane is excellent as Brooks and authentic in his portrayal of the retiring, erudite tutor who, too, falls prey to the gender roles of the time to not fully recognize that he needs to “man up” and help out Meg.

For her part Jo has witnessed in Meg’s and Brook’s quarreling, what she will never put herself through. Her identity, encouraged by Beth, Marmie (the wonderful Mary Bacon) and Meg’s trials with Brooks convince her she must forge her own sense of self and career path that is equivalent to those men which men achieve. Meg’s troubles assure her that her decision not to flirt with, capture a man’s heart then be oppressed and saddled with drudgery the rest of her life as his handmaid will never be her portion.

(L to R): Kristolyn Lloyd, Paola Sanchez Abreu, Primary Stages production of Kate Hamill’s adaptation of ‘Little Women’ (James Leynse)

Kristolyn Lloyd’s Jo is a dominant force, a powerhouse who is driven to express herself. With her soul, will and determination throughout the play again and again, Lloyd succinctly portrays how it is Jo’s nature to eschew being the passive, demure, “lady” who must portray an illusion to catch a man, then spend the rest of her life with him overthrowing that lie. Unlike Amy and Meg, she and Beth reject the repressive folkways which dictate how women must act, how they must look, what they must wear and do, as they take their final “resting place” at the bottom of society, absent power and authority, never to be heard from again. That is a death Jo and Beth will never die!

Initially, when Laurie (the vibrant Nate Mann makes the character charming, endearing, sensitive and adorable) joins the family and takes part as a swashbuckler in Jo’s plays, he accepts Jo’s strong identity though she continually throws off “being” the passive feminine. Laurie finds her enthralling and exciting company and adjusts his growing friendship by being real and loving. He notes that Joe sees herself like him and he appears to understand that she covets male power, authority and the freedom to take women’s freedom from them. This is why she revels acting the preeminent roles in her plays with Meg as the “damsel in distress” that she fights Laurie for.

Nate Mann, Kristolyn Lloyd, Primary Stages production of Kate Hamill’s adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s ‘Little Women’ (James Leynse)

The “play” scenes are humorous and cogently, precisely directed by Sarna Lapine and well-acted by Mann, Hamill, Abreu, Lloyd and Carmen Zilles as Amy who largely is their audience. These scenes establish each of the characters and reveal the undercurrents of why Jo must take on the dominant parts. We understand it is an attempt to work through what she finds completely obnoxious in the gender role of the passive, submissive, weak and helpless little lady that men find so alluring for they can come to their rescue and be the macho man. The artificiality and unreality of these roles annoys Jo, though Mann’s Laurie, inculcated to them since boyhood attempts to get Jo to play the damsel when Meg gets married. Her refusal is telling in another superb scene by Mann and Lloyd which foreshadows their maturation and Laurie’s love for her which Jo will never return as a lover. (Mann’s heartfelt upset when Lloyd’s Jo rejects him is beautifully rendered.)

The reversals are hysterical, as is Jo’s need to change the fake male-female dynamic. The humor in the overacting of Hamill’s Meg and Lloyd’s Jo to heighten the fake gender displacement is priceless and profound. That the enactment of the plays serves to reveal that Jo defines herself as equal to a man. Indeed, she intends to have the same notoriety and authority by making herself “someone recognized.” Though the culture would deny her, she will find a way, something Marmie, Meg (she is agreeable to join in the acting) and Beth encourage her to do with their acceptance and support. These scenes are powerful and filled with moment!

Kate Hamill, Michael Crane in the Primary Stages production of Kate Hamill’s adaptation of ‘Little Women’ (James Leynse)

The only one who does not accept Jo’s definition of herself and her way of being is Amy. Carmen Zilles convincingly portrays Amy as a spoiled, insistent, victim of Jo. Their disagreements not only move beyond rivalry, they represent opposing forces of womanhood. Amy has no ambition beyond marriage; and in a few funny bits aptly staged by Lapine, we see how she sets her designs on Laurie as she tries to get him to kiss her by standing under the mistletoe. At the conclusion of the play Amy insults Jo’s entire being and encourages her to give up her ambitions. We side with Jo’s anger against Amy; the burning of Jo’s book is tantamount to a blasphemy.

Amy brings to mind conservative women who marry well and stand by their man without a clue, staunchly upholding him regardless of the incorrectness of his position. She is Jo’s foil and their fights are inevitable so convinced are they of their definitions of themselves as women: Amy traditional, Jo a maverick forward thinker who wishes equality with men.

(L to R): Kate Hamill, Carmen Zilles, Ellen Harvey, Paola Sanchez Abreu, Kristolyn Lloyd in Primary Stages, ‘Little Women,’ Kate Hamill’s adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s novel (James Leynse)

Jo’s behavior at Aunt March’s (Mary Bacon is superb as the crotchety old woman) causes Amy to be taken to Europe instead of Jo. Amy’s vengeful burning of Jo’s only copy of her novel is the perfect raison d’etre for Jo to launch out on a new endeavor and succeed. Zilles and Lloyd shine in these dynamic scenes of argument and insult. Amy and Jo’s sustained oppositions spur each other on in the paths they’ve chosen with irony and humor. Without Jo, Amy would not be who she is; likewise for Jo. Their’s is a perfect match brought into focus in this fine rendering of Hamill’s Little Women whose elucidations of the themes and characterizations are revelatory and uniquely realized. Just marvelous.

Hamill’s adaptation of Little Women and Lloyd’s portrayal of Jo, Abreu’s Beth, Hamill’s Meg and Zilles’ Amy enlighten us to the power of entrenched gender roles whose folkways and stereotypes we wrestle with our entire lives. The ironies and themes of how each sister deals with these mores is incredible and found in no other adaptation of the novel that I have seen. Gobsmacking! Whether viewing for the depth of understanding or the pure fun and enjoyment and in Act II pathos of the family March, Little Women is a wondrous must see.

Special kudos to Mikiko Suzuki MacAdams for the functional and minimalistic set design. Much praise goes to Valerie Therese Bart’s superbly thought-out costumes and Paul Whitaker’s lighting design whose candles in Act II are heartfelt and atmospheric. Additional kudos to Leon Rothenberg for sound design, Dave Bova for wig and hair design, Michael G. Chin’s fight direction. Deborah Abramson’s original music between scenes is exceptional, atmospheric, lyrical. Without it the action would not have achieved such a seamless flow. The exuberance of Act I and the mellow seriousness of Act II would have been diminished in tone and tenor.

Little Women runs with one intermission at Cherry Lane Theatre (Commerce St.) until 29th June. Get your tickets before it is too late by CLICKING HERE.

‘Blue Ridge,’ An Examination of Soul Rehabilitation in North Carolina, Starring Marin Ireland

(L to R): Kyle Beltran, Kristolyn Lloyd, Nicole Lewis, Marin Ireland, Chris Stack, Peter Mark Kendall (foreground), in Atlantic Theater Company’s World Premiere of Abby Rosebrock’s ‘Blue Ridge,’ Linda Gross Theater (Ahron R. Foster)

How do we tell if our indignation for another’s plight isn’t our own misdirected rage that we ignore at our own peril? How is the healing process from childhood traumas that manifests through addiction to alcohol, drugs, sex and “acting out” initiated? Do those rehabilitating themselves recognize when the process evolves into wellness? How do such individuals recognize the journey to healing? Do they understand all that the arduous process entails before they attempt it? Or do they just move head on and try to change before they are ready because the culture and their anti-social behaviors demand it?

Atlantic Theater Company’s Blue Ridge written by Abby Rosebrock and directed by Taibi Magar raises these questions and many more. The play is superb, but does fall a bit short on one element, despite the fine performances by the ensemble and the excellent production values. The weakness evidences in Rosebrock’s sometimes confounding redirection of focus in examining the protagonist Alison (a nuanced, and layered performance by Marin Ireland whose accent is, at times, ill-executed because she quickly glosses over important, profound lines). Nevertheless, Rosebrock’s work is exceptional in the service of revealing themes which initiate organically from her characters and their interactions with each other, as they rehab in a group home setting.

Marin Ireland, Peter Mark Kendall in Abby Rosebrock’s ‘Blue Ridge,’ Atlantic Theater Company World Premiere, Linda Gross Theater (Ahron R. Foster)

Currently at the Linda Gross Theater, Blue Ridge takes place at a religious rehabilitation retreat in the gorgeous mountains of western North Carolina (Appalachia). Everpresent are the fundamentalist tenets of Christianity which the characters attempt to espouse and practice. There, at St. John’s Service House, the individuals who have been interviewed and accepted for placement, seek God’s love, forgiveness, joy and peace, reinforced by Sunday church, Wednesday Bible Study, meditation, outside jobs at a pool store and therapeutic group conversation.

However, the process of moving toward wellness is not as easy as it may appear with prayers and Bible work. There must be a complete revolution of one’s soul, a very tricky circumstance indeed; for what is the soul? What is sin? What is the devil? And how do Christian teachings answer psychological traumas? As a key theme which Rosebrock brilliantly reveals, dealing with trauma involves more intricate and complex understanding on a personal level for those who experienced trauma. This involves a life-long process and everyone who undergoes it won’t find any marked yellow brick road at the end of the rainbow. But a good first step is remembering and confronting the trauma alone and/or with expert guidance and love.

Nicole Lewis in the Atlantic Theater Company’s World Premiere of Abby Rosebrock’s ‘Blue Ridge’ Linda Gross Theater (Ahron R. Foster)

The characters, some with overseeing functions like Hern (the pastor played by Chris Stack) and Grace (social worker portrayed by Nicole Lewis) help others, and with empathy and service, seek to rehabilitate themselves. Those, like Alison (Marin Ireland) Wade (Kyle Beltran) and Cole (Peter Mark Kendall), who have been accepted into the program, hope to correct problems which have manifested in self-destructive behaviors. If such behaviors continue, the individuals will be sent to restrictive settings (jail or psychiatric lock up), if they do not improve and heal. Other characters like Cherie (Kristolyn Lloyd), voluntarily enroll in the program. Cherie knows her own soul’s weaknesses related to her family’s and her own alcoholism. Though she is self-aware, she is blind to her other weaknesses and these set her on a course which may lead to relapse if not confronted.

Rosebrock introduces us to the principals in the first act which largely is humorous exposition to set up the dramatic developments and the climax of the second act. The characters are representational, some with individual problems that run deep but whose cause remains unknown. Their outward issues range from alcohol and drug addictions to anger management issues identified euphemistically as “intermittent explosive disorder.”

Central to the characters’ improvement and social reconstitution is the Wednesday Bible Study where we first meet the others and Alison, a teacher who lost her way and her job because of anger management issues. Alison chose to go to rehab rather than jail for destroying her principal’s car; ironically, he also was the man she “loved.” Marin Ireland’s portrayal reveals Alison’s fierce, hyperbolic and frenetic personality which masks the underlying wounds which Rosebrock intimates but doesn’t clarify by the conclusion of the play.

Marin Ireland in Atlantic Theater Company’s World Premiere of Abby Rosebrock’s ‘Blue Ridge,’ Linda Gross Theater (Ahron R. Foster)

A word about the character of Alison, who is the linchpin of Rosebrock’s work. One wonders if the play’s dynamism might have been strengthened if Rosebrock had more clearly and with dramatic and active plot points heightened the true issues that fomented Alison’s life-long devastation. At the beginning of Act One, to introduce herself, Alison glibly races through the lines of a song “Before He Cheats” by Carrie Underwood which parallels her behavior that landed her in rehab. We understand that she refers to herself when she quotes: “by this point all the accumulated pain an’ hopelessness, an’ annihilatin degradation, uh’bein a woman in this sexual economy’ve juss… racked the speaker’s brain and body, like a cancer.”

However, we remain unenlightened about the how and the what, even until the end of the play when Wade (Kyle Beltran) confronts her with these lines. Rosebrock never delineates the specifics of Alison’s annihilation and this is key to feeling empathy for her. Though Ireland does a yeowoman’s job in getting us to Alison’s heightened emotional state, our identification with her is muted and unsatisfactory. Perhaps, this is because we do not understand why she hurts so on an individual level. It is not enough to call in the cultural memes as her revelation. The facts and specifics matter; they resonate. But what are they? Thus the fullness and the power of Alison’s emotional state and whether or not she has achieved self-realization to move on to the healing process is opaque. We are not even “seeing through a glass darkly” where she is concerned.

Kyle Beltran in Atlantic Theater Company’s World Premiere of Abby Rosebrock’s ‘Blue Ridge,’ Linda Gross Theater (Ahron R. Foster)

The play turns on Alison’s integration into the program and her recovery. The irony is that she does the work in achieving her external goals and is reinstated as a teacher. However, she doesn’t begin to expurgate the underlying morass of pain in her soul while she is immersed in her sessions and interactions with Wade, Cherie, Hern, Cole, Grace. Indeed, because her self-realizations remain superficial, she becomes the catalyst that exacerbates conflicts and escalates issues for Cherie, Hern, Cole and Grace. As Cherie suggests, Alison blows up a set of circumstances via her own projections. As a result, everything changes for the characters.

Furthermore, Alison doesn’t understand how to get around the humiliation of the negative impact she has afterward. Ironically, though “all have sinned and come short of the glory of God,” by the end of the play, we see though there are apologies, there is no closure, no forgiveness, no resolution. Each of the individuals is forced to work by himself/herself as the “family” goes its own way in separate directions.

The only one who attempts to deal with himself in an authentic way is Wade. He tries to “make amends” for his not dealing with Alison on a deeper level than he he should have. At the conclusion Wade’s conversation with her is a trigger. However, we do not understand the specifics of the how or why. The rationale appears that she went through something in childhood. So did we all. We are ready to empathize, but are never quite given the chance, a fissure in the play’s development and characterization of Alison.

Rosebrock chooses to develop the play so that the conclusion becomes Alison’s flashpoint of experiencing the pain of her buried, bleeding wounds. The play ends with her emotional breakdown as she appears to allow herself to feel on a deeper level.

This is a risky choice in developing the play.The outcome remains unsatisfying and uncertain. The character Alison, whom we’ve come to accept and appreciate, is a cipher and a conundrum to herself and us. Though Alison has achieved the beginnings of a deep emotional release, Rosebrock sets her spinning in limbo. Any epiphany she might experience is mitigated by questions and doubt. We do not know where her emotional release will take her, nor what specifically it is connected to.

(L to R): Chris Stack, Kristolyn Lloyd in Atlantic Theater Company’s World Premiere of ‘Blue Ridge,’ written by Abby Rosebrock, directed by Taibi Magar, Linda Gross Theater (Ahron R. Foster)

If we did know more about what is “driving her to hydroplane” (a wonderful symbol of her dangerous emotional state), we might have greater empathy. And indeed, if she achieved the makings of an epiphany, we would understand her. The irony is that her emotions belie victimization but we do not understand. Might that have been dramatically revealed to deepen her characterization?

Magar’s direction aptly shepherds the cast as they portray how each of the characters attempts to make their way through their own personal trials that emerge after Alison blows apart the peaceful interactions of the “family” in the second act. These conflict scenes engage us. In the confrontation scene between Alison and Cherie toward the end of the second act, both Lloyd and Ireland hit their target. Their authenticity reveals the extent of Alison’s self-absorption and her misery which spills out onto everyone in the group, especially harming Cherie. This scene is one of the strongest in the play. There are others that work equally well because of fine ensemble work, direction and staging.

Kudos to Adam Rigg (Scenic Designer), Sarah Laux (Costume Designer) Amith Chandrashaker (Lighting Designer) and Mikaal Sulaiman (Sound Designer & Additional Composition) for adhering to themes and establishing the tenor and atmosphere of the play. (The final projection is revelatory and symbolic.)

A word of caution. For some actors, the North Carolinian accents were a distraction that occluded rather than clarified. Whether this was because of character portrayal or under-projection is moot. However, because Kyle Beltran, Kristolyn Lloyd, Peter Mark Kendall (to a lesser extent Chris Stack) didn’t overrun their lines and their projection was a sounding bell, their accents sounded unforced.

The play is a worthy must-see for the performances (despite a few rough patches with accents) and for Rosebrock’s metaphoric writing, humor and intriguing thematic questions. Blue Ridge runs with one intermission at the Linda Gross Theater on 336 20th Street between 7th and 8th until 26 January. For tickets go to the website.