Blog Archives

‘The Baker’s Wife,’ Lovely, Poignant, Profound

It is easy to understand why the musical by Stephen Schwartz (music, lyrics) and Joseph Stein (book) after numerous reworkings and many performances since its premiere in 1976 has continued to gain a cult following. Despite never making it to Broadway, The Baker’s Wife has its growing fan club. This profound, beautiful and heartfelt production at Classic Stage Company directed by Gordon Greenberg will surely add to the fan club numbers after it closes its limited run on 21 December.

Based on the film, “La Femme du Boulanger” by Marcel Pagnol (1938), which adapted Jean Giono’s novella“Jean le Bleu,” The Baker’s Wife is set in a tiny Provençal village during the mid-1930s. The story follows the newly hired baker, Aimable (Scott Bakula), and his much younger wife, Geneviève (Oscar winner, Ariana De Bose). The townspeople who have been without a baker and fresh bread, croissants or pastries for months, hail the new couple with love when they finally arrive in rural Concorde. Ironically, bread and what it symbolically refers to is the only item upon which they readily agree.

If you have not been to France, you may not “get” the community’s orgasmic and funny ravings about Aimable’s fresh, luscious bread in the song “Bread.” A noteworthy fact is that French breads are free from preservatives, dyes, chemicals which the French ban, so you can taste the incredible difference. The importance of this superlative baker and his bread become the conceit upon which the musical tuns.

Schwartz’s gorgeously lyrical music and the parable-like simplicity of Stein’s book reaffirm the values of forgiveness, humility, community and graciousness as they relate to the story of Geneviève. She abandons her loving husband Aimable and runs away to have adventures with handsome, wild, young Dominique (Kevin William Paul), the Marquis’ chauffeur. When the devastated Aimable starts drinking and stops making bread, the townspeople agree they cannot allow Aimable to fall down on his job. The Marquis (Nathan Lee Graham), is more upset about losing Aimable’s bread than the car Domnique stole.

Casting off long held feuds and disagreements, they unite together and send out a search party to return Geneviève without judgment to Aimable, who has resolved to be alone. Meanwhile, Geneviève decides to leave Dominique who is hot-blooded but cold-hearted. In a serendipitous moment three of the villagers come upon Geneviève waiting to catch a bus to Marseilles. They gently encourage her to return to Concorde, affirming the town will not judge her.

She realizes she has nowhere to go and acknowledges her wrong-headed ways, acting like Pompom her cat who also ran off. Geneviève returns to Aimable for security, comfort and stability, and Pompom returns because she is hungry. Aimable feeds both, but scolds the cat for running after a stray tom cat in the moonlight. When he asks Pompom if she will run away again, DeBose quietly, meaningfully tells Bakula’s Aimable, she will not leave again. The understanding and connection returns metaphorically between them.

Director Gordon Greenberg’s dynamically staged and beautifully designed revival succeeds because of the exceptional Scott Bakula and perfect Ariana DeBose, who also dances balletically (choreography by Stephanie Klemons). DeBose’s singing is beyond gorgeous and Bakula’s Aimable resonates with pride and poignancy The superb ensemble evokes the community of the village which swirls its life around the central couple.

Greenberg’s acute, well-paced direction reveals an obvious appreciation and familiarity with The Baker’s Wife. Having directed two previous runs, one in New Jersey (2005), the other at The Menier Chocolate Factory in London (2024), Greenberg fashions this winning, immersive production with the cafe square spilling out into the CSC’s central space with the audience on three sides. The production offers the unique experience of cafe seating for audience members.

Jason Sherwood’s scenic design creates the atmosphere of the small village of Concorde with ivy draping the faux walls, suggesting the village’s quaint buildings. The baker’s boulanger on the ground floor at the back of the theater is in a two-story building with the second floor bedroom hidden by curtains with the ivy covered “Romeo and Juliet” balcony in front. The balcony features prominently as a device of romance, escape or union. From there DeBoise’s Geneviève stands dramatically while Kevin William Paul’s Dominique serenades her, pretending it is the baker’s talents he praises. From there DeBoise exquisitely sings “Meadowlark.”

Greenberg’s vision for the musical, the sterling leads and the excellent ensemble overcome the show’s flaws. The actors breathe life into the dated script and misogynistic jokes by integrating these as cultural aspects of the small French community of Concorde in the time before WW II. The community composed of idiosyncratic members show they can be disagreeable and divisive with each other. However, they come together when they attempt to find Geneviève and return her to Aimable to restore balance to their collective, with bread for their emotional and physical sustenance.

All of the wonderful work by ensemble members keep the musical pinging. Robert Cuccioli plays ironic husband Claude with Judy Kuhn as his wife Denise. They are the cafe owning, long married couple, who serve as the foils for the newly married Aimable and Geneviève. They provide humor with wise cracks about each other as the other townspeople chime in with their jokes and songs about annoying neighbors.

Like the other townspeople, who watch the events with the baker and his wife and learn about themselves, Claude and Denise realize the lust of their youth has morphed into love and great appreciation for each other in their middle age. Kuhn’s Denise opens and closes the production singing about the life and people of the village who gain a new perspective in the memorable signature song, “Chanson.”

The event with the baker and his wife stirs the townspeople to re-evaluate their former outlooks and biased attitudes. The women especially receive a boon from Geneviève’s actions. They toast to her while the men have gone on their search, leaving the women “without their instruction.” And for the first time Hortense (Sally Murphy), stands up to her dictatorial husband Barnaby (Manu Narayan) and leaves to visit a relative. She may never return. Clearly, the townspeople inch their way forward in getting along with each other, to “break bread” congenially as a result of an experience with “the baker and his wife,” that they will never forget.

The Baker’s Wife runs 2 hours 30 minutes with one intermission at Classic Stage Company through Dec. 21st; classicstage.org.

Lesley Manville and Mark Strong are Mindblowing in ‘Oedipus’

Just imagine in our time, a leader with integrity and probity, who searches out the truth, no matter what the cost to himself and his family. In Robert Icke’s magnificent reworking of Sophocles’ Oedipus, currently at Studio 54 through February 8th, Mark Strong’s powerful, dynamically truthful Oedipus presents as such a man. Likewise, Lesley Manville’s lovely, winning Jocasta presents as his steely, supportive, adoring help-meet. Who wouldn’t embrace such a graceful couple as the finest representatives to govern a nation?

Sophocles’ classic Greek tragedy, that defined the limits of the genre and imprinted on theatrical consciousness the idea that a tragic hero’s hubris causes his destruction, evokes timeless verities. In his updated version, Icke, who also directs, superbly aligns the characters and play’s elements with today’s political constructs. Icke retains the names of the ancient characters. This choice spurs our interest. How will he unravel Sophocles’ amazing Oedipus tragedy, especially the conclusion?

Cleverly, he presents Oedipus as a political campaigner of a fledgling movement that over a two-year period gains critical mass. The director reveals Oedipus’ backstory in a filmed speech to reporters on the eve of the election. The excellent video design is by Tal Yarden.

During his speech Oedipus goes off book and makes promises. Though his brother-in-law Creon (the fine John Carroll Lynch) tries to stop him, proudly Oedipus shows himself a man of his word. He galvanizes the crowd when he states he will expose the lies of his opponents. Not only will he reveal his birth certificate (an ironic reference to President Obama), he will investigate the mysterious death of Laius. The former leader from decades ago married Jocasta when she was a teenager. After Laius’ death, Oedipus meets and marries Jocasta despite their age difference. Over the years they raise three children: Antigone (Olivia Reis), Eteocles (Jordan Scowen) and Polyneices (James Wilbraham).

How has Oedipus become the people’s candidate? Without ties to the political system, he speaks a message of reform and justice. Indeed, he will override the corrupt, derelict power structure. Former leaders served their rich donors and let the other classes suffer. Oedipus runs on a mandate of equity and change.

After Oedipus’ speech, the curtain opens to reveal the campaign headquarters that staff gradually dismantles as the campaign phase ends. To signify the next phase the countdown clock, placed conspicuously in scenic designer Hildegard Bechtler’s headquarters, ticks away the seconds down to the announcement of the winner. As the clock ticks toward zero (an ironic symbol), the contents of the campaign war room are removed like the peeling of an onion to its core. As the destined announcement of the winner nears, gradually, the revelation of Oedipus’ true identity happens. Icke has synchronized both concurrently.

Icke’s anointed idea to shape Oedipus as a newbie politician, whose actions and words are singularly unified in honesty, resonates. He represents the iconic head of state we all yearn for and believe in, forgetting leaders are flesh and blood. Of course Icke’s flawed tragic hero, like Sophocles’ ancient one, results in Oedipus’ prideful search for the truth of his origin story and Laius’ cause of death.

Oedipus’s determination is spurred by the cultist future-teller Teiresias (the superb Samuel Brewer). His authoritative and relentless drive to prove Teiresias wrong, despite warnings from Creon and Jocasta, shows persistence and courage, positive leadership qualities. On the other hand, Oedipus doesn’t realize his search has a dark side and his persistence is stubbornness prompted by a prideful ego. This stubbornness causes his destruction. His pride leaves no way out for him but punishment.

Because the truth is so horrid, Strong’s Oedipus can’t suffer himself to cover it up. In searching to validate his true self, he discovers the flawed human that Teiresias proclaims. Indeed, he is more flawed than most. He is lurid; a man who killed his father, married his mother, and had three children born out of love, lust and incest. He can never be the leader of the nation. He must hold himself accountable after he sees his debased true self. How Mark Strong effects Oedipus’ self-punishment is symbolic genius. Clues to Jocasta’s end are sneakily tucked in earlier.

Because of Icke’s acute shepherding of the actors, and the illustrious performances of Manville, Strong and Brewer, with the cast’s assistance, we feel the impact of this tragedy. The love relationship between Jocasta and Oedipus, drawn with two passionate scenes by Manville and Strong, especially the last scene, after they acknowledge who they are with one, long, silent look, devastates and convicts.

Those who know the story feel a confluence of emotions at the irony of mother and son lustily loving and pursuing their desire for each other off stage, while Oedipus delays speaking to his mother Merope (Anne Reid). Manville and Strong are extraordinary. Both actors convey the beauty, the wildness, the uniqueness and enjoyment of their characters’ love, that is unlike any other.

In the last scene when Strong and Manville untangle from their hot grip, clinging to each other then letting go, they acknowledge their characters’ unfathomable and great loss. Manville’s Jocasta crawls away to reconcile the enormity of what she has done. In her physical act of crawling then getting up, we note that fate and their choices have diminished their majestic grace. Their sexual likeness to animals, Oedipus ironically referenced earlier with family at the celebration dinner. Through the physical staging of the final sexual scene, Icke recalls Oedipus’ earlier comparison.

As a meta-theme of his version Icke reminds us of the importance of humility. The more humanity presents its “greatness,” the more it reveals its base nature.

All the more tragedy for Oedipus’ supporters and the unnamed country. Because fate catches up with him and conspires with him to cut off his acceptance of the position he rightfully won, the nation loses. All the more sorrow that the truth and his honest search is what Oedipus prizes, even more than his love for Manville’s Jocasta, the brilliant, equivalent match for Strong’s Oedipus.

Rather than live covertly hiding their actions, both Oedipus and Jocasta hold themselves accountable with a fatalistic strength and nobility. Initially, we learn of her strength as Jocassta tells Oedipus about her experience with the evil Laius (a reference to current political pedophiles and rapists). We see her strength in her self-punishment. Likewise, Oedipus’ strength compels him to face his deeds where cowards would cover up the truth, step into the position and govern autocratically censoring and/or killing their opponents who would “spill the beans.” Oedipus is not such a man. It is an irony that he is a moral leader, but is unfit to lead.

Icke’s masterwork and Manville and Strong’s performances will be remembered in this great production, filled with ironic dialogue about sight, vision, blindness and comments that allude to Oedipus and Jocasta’s incestuous relationship and downfall. Those familiar with the tragedy will get lines like Jocasta’s teasing Oedipus, “You’ll be the death of me,” and her telling people she has four children: “two at 20, one at 23, and one at 52.”

Though I prefer Icke’s ending in darkness with the loud cheers of the supporters, I “get” why Icke ends Oedipus in a flashback. In the very last scene the date is 2023, the beginning of the end. We watch the excited Oedipus and Jocasta choose the rented space (the stripped stage) for their campaign headquarters. The time and place mark their disastrous decision which spools out to their destruction two years later. I groaned with Jocasta’s ironic comment, “It feels like home.”

Her comment resonates like a bomb blast. If Oedipus had not had the vision of himself as the ideal, righteous leader with truth at his core, the place where they are “at home” never would have been selected. Oedipus, a humble mortal, never would have run for high office.

Oedipus runs 2 hours with no intermission at Studio 54 though February 8. oedipustheplay.com.

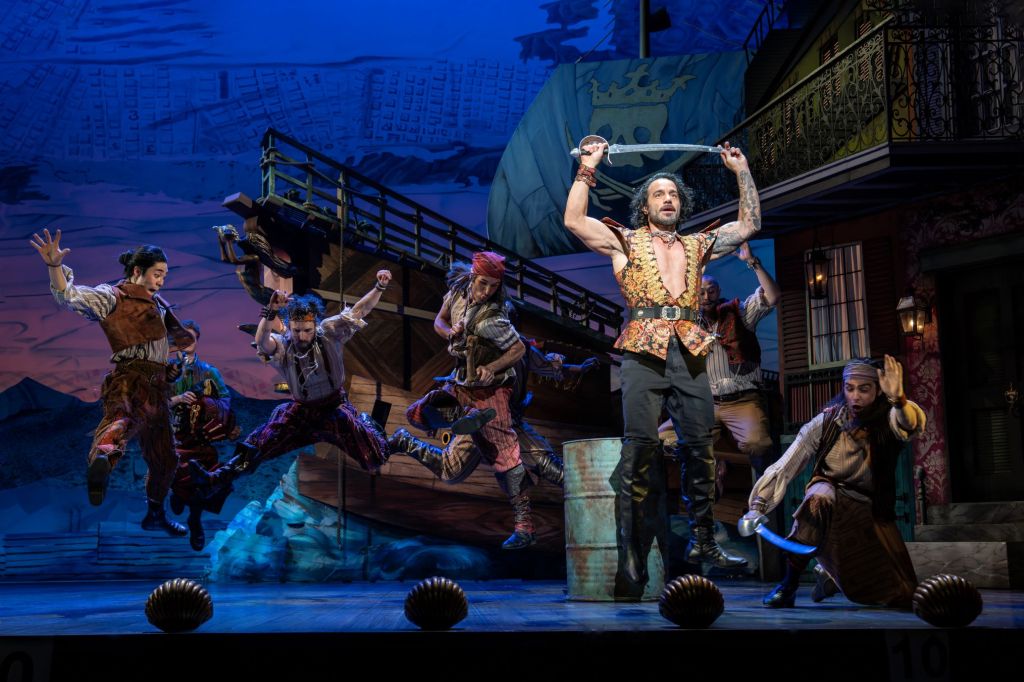

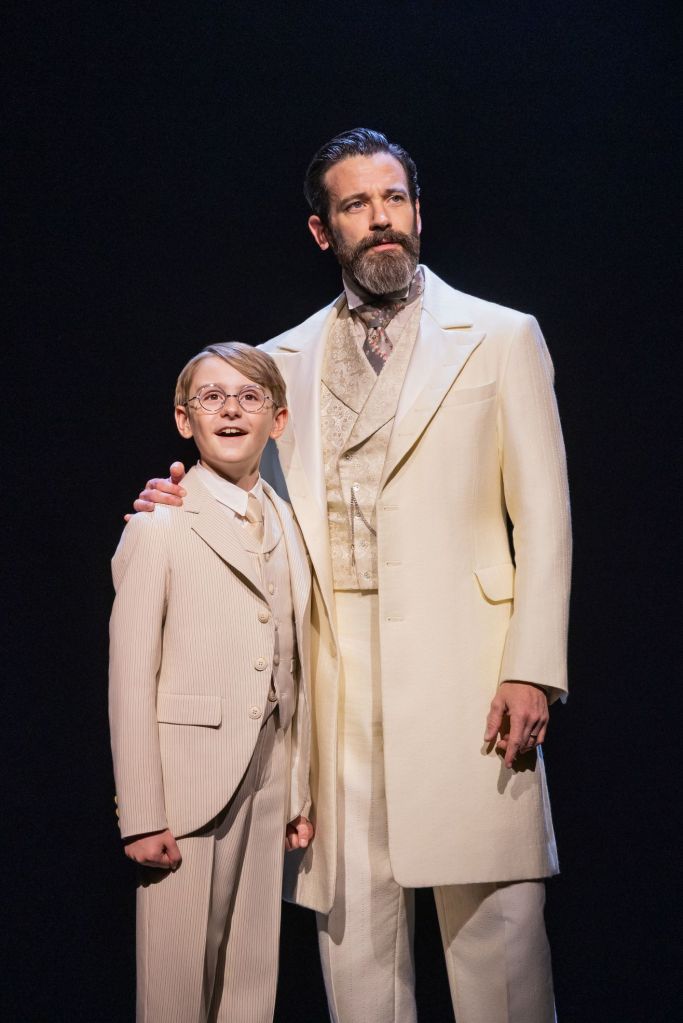

‘Ragtime’ is Magnificent and of Incredible Moment

Between the time Lear DeBessonet’s Ragtime graced New York City Center with its Gala Production in 2024, until now with the opening of DeBessonet’s revival at Lincoln Center, our country has gone through a sea change. The very core of its values which uphold equal justice, civil rights and due process are under siege. Because our democratic processes are being shaken by the current political administration, there isn’t a better time to revisit this musical about American dreamers. Ragtime currently runs at the Vivian Beaumont Theater until January 4.

DeBessonet has kept most of the same cast as in the City Center Production. The performers represent three families from different socioeconomic classes. In each instance, they face the dawning of the 20th century with hope to maintain or secure “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” in a country whose declaration asserted independence from its king. In affirming “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all ‘men’ are created equal,” America’s promises to itself are fulfilled by its citizens. Ragtime reveals who these citizens may be as they strive toward such promised freedoms.

Above all Ragtime is about America, the saga of a glorious and terrible America, striving to manifest its ideals and live up to them, despite overarching forces that would slow down and halt the process.

Based on E. L. Doctorow’s classic 1975 historical novel, and adapted for the stage by Terrence McNally (book), Stephen Flaherty (music), and Lynn Ahrens, (lyrics), Ragtime‘s immutable verities are heartfelt and real. As such, it’s a consummate American musical. DeBessonet’s production celebrates this, and superbly presents the beauty, tragedy and hope of what America means to us. In its concluding songs (Coalhouse’s “Make Them Hear You,” and the company’s “Ragtime/Wheels of a Dream”), the performers express a poignant yearning. Sadly, their choral pleading is a stunning and painful reminder of how far we have yet to go to thoroughly uphold our constitution.

The opening number “Ragtime,” introduces the setting, characters and suggested themes. Here, DeBessonet’s vision is in full bloom, from the lovely period costumes by Linda Cho, David Korins’ minimally stylized scenic design, DeBessonet’s staging, and Ellenore Scott’s choreography. As the company sings with thrilling power and grace, they gradually move forward to take center stage. They are one unit of glorious interwoven diversity and destiny. The audience’s applause in reaction to the soaring music and stunning visual and aural presentation, heightened by a bare stage, emotionally charged the performers. Thematically, the cast had an important mandate to share, a cathartic revelation of the sanctity of American values, now on the brink of destruction.

Watching the unfolding of events we cheer for characters like the talented Harlem pianist and composer of ragtime music, Coalhouse Walker, Jr. (the phenomenal Joshua Henry). And we identify with the ingenious, Jewish immigrant Tateh (the endearing Brandon Uranowitz). Tateh must succeed for the sake of his little daughter (Tabitha Lawing), despite their impoverished Latvian background. Likewise, we champion Mother (the superb Caissie Levy), who reveals her decency, kindness and skill, running the house, family and business. She must fill in the gap while her husband (Colin Donnell), goes on a lengthy expedition to the North Pole as a man of the privileged, upper class patriarchy.

The musical also reflects the other side of America’s blood-soaked history, best represented by characters along a continuum. Their misogyny, discrimination and greed often overwhelm, victimize and institutionalize innocents in the name of a just progress. These include tycoons like J.P. Morgan, Henry Ford, and the garden variety racists that brutalize Coalhouse Jr. and his partner Sarah (the fine Nichelle Lewis), in the name of order and security. Finally, to inspire all, the musical includes wily entrepreneurs like Harry Houdini (Rodd Cyrus), social justice advocates like Emma Goldman (the wonderful Shaina Taub), and accepted reformers like Booker T. Washington (John Clay III). All these individuals make up the living fabric of America.

At its most revelatory, Ragtime exposes elements of our present as the continuation of entrenched issues never resolved from our past. Despite our great strides in nuclear fission and quantum computing, retrograde darkness still lurks in the nation’s beating heart, in its violence, in its human rights inequities. Clear-eyed, incisive, DeBessonet’s spare choices about spectacle and design, and her focus on great acting and singing by the leads and ensemble, ground this masterwork.

Ragtime begins with an interesting unexplained entrance: a winsome and beautiful Black male child in period dress frolics across a bare stage. At the conclusion the circle comes to a close and he appears again. We discover who he is and what he symbolizes in a stark, crystallizing moment of elucidation. After the opening number (“Ragtime”), Mother’s adventure as head of her household begins when Father leaves (“Goodbye My Love”). Her helpers include her outspoken, prescient, son Edgar (Nick Barrington), her younger brother (Ben Levi Ross), and her opinionated, crotchety father (Tom Nelis).

However, the peace and serenity of their lives become interrupted when Mother discovers an abandoned baby in her garden. After much deliberation, Mother takes in the infant and traumatized mother, Sarah. Clearly, this startling act of redemption never would have occurred if Father was present. As an assertion of Mother’s right to make her own decisions, her grace becomes a turning point in the lives of the baby’s father, Coalhouse, and his love, Sarah. Apparently, Coalhhouse left Sarah to travel for his career, not knowing she was pregnant. He was pursing his dream of being a singer/composer of the new ragtime music.

By he time Coalhouse searches for Sarah to eventually find and woo her back to him, we note the tribulations of Tateh, who tries to survive using his artistic skills (like Harry Houdini). And we note the moguls of a corrupted capitalism, i.e. Ford, Morgan (“Success”), who Emma Goldman accuses of exploitation. They keep the workers and society oppressed and poor.

Using his charm and daily persistence (“he Courtship,” “New Music,”), Coalhouse wins Sarah back. In a dramatic, dynamic moment, Henry’s Coalhouse sings with emotion, “Sarah, come down to me.” When Lewis’ Sarah descends, their fulfillment together is paradise. The stunning scene like the ones that follow, i.e. “New Music,” and especially Henry and Lewis’ “Wheels of a Dream,” where Coalhouse and Sarah sing to their son about America, are hopeful and heartbreaking. Again, the audience stopped the show with applause and cheers as they periodically did throughout the production.

On the wave of Coalhouse and Sarah’s togetherness and love reunited, we forget the underbelly of a dark America that looms around the corner. It does appears during Father’s reunion with Mother after his lengthy voyage.

Unhappily, Father returns to a household in chaos with Sarah, Coalhouse and the baby under his roof. He can’t imagine what “got into” his wife and makes demeaning remarks about the baby. His conservative, un-Christian-like attitude upsets Mother. She defends her position and replies with demure, feminine instruction. Interestingly, her comment indicates she will not heel to him like the good lap dog she was before he left. As with the other leads, Levy’s performance is unforgettable in its specificity, nuance and authenticity.

Clearly, the characters have made inroads with each other bringing socioeconomic classes together during events when activists like Emma Goldman and Booker T. Washington make their mark and reaffirm equality. As a representative of the wave of immigrants coming to America from other teeming shores, Uranowitz’s Tateh steals our hearts and pings our consciences, thanks to his human, loving portrayal. Despite his bitterness in having to brace against the poverty he came to escape, he tries to overcome his circumstances and with ingenuity and pluck continually perseveres. Uranowitz’s Tateh particularly makes us consider the current government’s cruel, unconstitutional response toward migrants and immigrants today.

Act II answers the conflicts presented in Act I, leaving us with a troubling expose of our country’s heart of darkness. Yet, the musical uplifts bright halos of hope with the return of the adorable Black male child. We discover who he is and understand his mythic symbolism. Also, we learn the fate of the characters, some justly deserved. And the audience leaves remembering the cries of “Bravo” that resounded in their ears for this mind-blowing production.

Ragtime

With music direction by James Moore Ragtime runs 2 hours 45 minutes with one intermission through Jan. 4 at the Vivian Beaumont Theater lct.org.

‘The Burning Cauldron of Fiery Fire,’ Anne Washburn’s Challenging, Original Play

Known for its maverick, innovative productions, the Vineyard Theatre seems the perfect venue for Anne Washburn’s world premiere, The Burning Cauldron of Firey Fire. Poetic, mysterious and engaging, Washburn places characters together who represent individuals in a Northern California commune. When we meet these individuals, they have carved out their own living space in their own definition of “off the grid.” Comprised of adults and children, their intention is to escape the indecent cultural brutality of a corrupt American society, where solid values have been drained of meaning.

Coming in at 2 hours, 5 minutes with one 15 minute intermission, the actors are spot-on and the puppetry engages. However, the play sometimes confuses with director Steve Cosson’s opaque dramatization of Washburn’s use of metaphor, poetry and song. More clearly presented in the script’s stage directions, the production doesn’t always theatricalize Washburn’s intent. Certainly, the themes would resonate, if the director had made more nuanced, specific choices.

The plot about characters who confront death in their commune in Northern California unfolds with the stylized, minimal set design by Andrew Boyce, heavily dependent on props to convey a barn, a kitchen and more. The intriguing lighting design by Amith Chandrashaker suggests the beauty of the surrounding hills and mountains of the north country where the commune makes its home.

The ensemble of eight adult actors takes on the roles of 10 adults and 8 children. Because the structure is free-flowing with no specific clarification of setting (time), it takes a while to distinguish between the adults and children, who interchange roles as some children play the parts of adults. The scenes which focus on the children (for example at the pigpen) more easily indicate the age difference.

The conflict begins after the members of the commune burn a fellow member’s body on a funeral pyre to honor him. Through their discussion, we divine that Peter, who joined their commune nine months before, has committed suicide, but hasn’t left a note. Rather than to contact the police and involve the “state,” they justify to themselves that Peter wouldn’t have wanted outside involvement. Certainly, they don’t want the police investigating their commune, relationships and living arrangements which Washburn reveals as part of the mysterious circumstances of this unbounded, “bondage-free,” spiritual community.

Nevertheless, Peter’s death has created questions which they must confront as tensions about his death mount. Should they reburn his body which requires the heat of a crematorium to reduce it to ashes? After the memorial fire, they decide to bury him in an unmarked grave, which must be at a depth so that animals cannot dig up his carcass. Additionally, if they keep any of Peter’s belongings, which ones and why? If someone contacts them, for example Peter’s mother, what story do they tell her in a unity of agreement? Finally, how do they deal with the children who are upset at Peter’s disappearance?

We question why they feel compelled to lie about Peter’s disappearance, rather than tell the truth to the authorities or Peter’s mom, even if they can receive her calls on an old rotary phone. Thomas, infuriated after he speaks to Peter’s mom who does call, tells her Peter left with no forwarding address. After he hangs up, Thomas (Bruce McKenzie) self-righteously goes on a rant that he will tear down the phone lines.

When Mari (Marianne Rendon) suggests they need the phone for emergency services, he counters. “Can anyone give me a compelling argument for a situation in which this object is likely to protect us from death because let me remind you that if that is its responsibility we have a recent example of it failing at just that.”

Indeed, the tension between commune members Thomas, Mari, Simon (Jeff Biehl), Gracie (Cricket Brown) and Diana (Donnetta Lavinia Grays) becomes acute with the threat of outside interference destabilizing their peaceful, bucolic arrangements. Washburn, through various discussions, brings a slow burn of anxiety that displaces the unity of the members as they work to hide the truth. What begins at the top of the play as they burn the body in a memorial ceremony that allows Thomas and the group to take philosophical flights of fancy, augments their stress as they avoid looking at hard circumstances.

Fantasy and reality clash also In the well-wrought scene where the actors portray the children moving the piglet they believe is Peter when it reacts to Peter’s belongings, specifically, a poem it chews on. Convinced Peter has been reincarnated and is with them, they take the piglet staunching their upset at Peter’s death by reclaiming and renaming the piglet as the rescued Peter. Rather than to have explained what happened, the commune members allow the children to believe another convenient lie.

This particularly well-wrought, centrally staged scene of the children in the pigsty works to explicate the behavior of the commune members. They don’t confront Peter’s death and don’t allow the children to either. The actors captivate as they become the children who relate to the invisible mom Lula and her piglets with excitement, concern and hope. It is one of the highpoints of the production because in its dramatization, we understand the faults of the commune. Also, we understand by extension a key theme of the play. Rather than confronting the worst parts of their own inhumanity, people close themselves off, escape and make up their own fictional worlds.

Washburn reveals the contradictions of this commune who parse out their ideals and justify their actions “living away from society.” Yet they cannot commit to this approach completely because of the extremism required to disconnect from civilization. As it is, they have a car, they do mail runs and sometimes shop at grocery stores. At best their living arrangement is as they agree to define it and as Washburn implies, half-formed and by degrees runs along a continuum of pretension and posturing.

The issues about Peter’s death come to a climax when Will (Tom Pecinka), Peter’s brother, shows up to investigate what happened to Peter. Washburn ratchets up the suspense, fantastical elements and ironies. Through Will we discover that Peter was an estranged, trust-fund baby who will inherit a lot of money from his grandmother who is now dying. Ironically, we note that Mari who claims she had an affair with Peter and dumped him (the reason why he “left”), is willing to have sex with Will. They close out a scene with a passionate kiss. Certainly, Will has been derailed from suspecting this group of anything sinister.

Also, Will is thrown off their lies when he watches a fairy-tale-like playlet, supposedly created by Peter and the children that is designed to lull the watcher with fanciful entertainment.

In the fairy tale a cruel king (the comical and spot-on Donnetta Lavinia Grays), prevents his princess daughter (Cricket Brown) from marrying her true love (Bartley Booz), also named Peter. The bad king thwarts Peter from winning challenges to gain the princess’ love. Included in the scenarios are puppets by Monkey Boys Productions, special effects (Steve Cuiffo consulting), the burning cauldron of fiery flames with playful fire fishes proving the flames can’t be all that bad, and a beautiful, malevolent, dangerous-looking dragon who threatens.

Once again creatives (Boyce, Chandrashaker and Emily Rebholz’s costumes) and the actors make the scene work. The clever, make-shift, DIY cauldron, puppets and dragon allow us to suspend our judgment and willingly believe because of the comical aspect and inherent messages underneath the fairy-tale plot. Especially in the last scene when Peter (the poignant Tom Pecinka), cries out in pain then makes his final decision, we feel the impact of the terrible, the beautiful, the mighty. Thomas used these words to characterize Peter’s death and their memorial funeral pyre to him at the play’s outset. At the conclusion the play comes full circle.

Washburn leaves the audience feeling the uncertainties of what they witnessed with a group of individuals eager to make their own meaning, regardless of whether it reflects reality or the truth. The questions abound, and confusion never quite settles into clarity. We must divine the meaning of what we’ve witnessed.

The Burning Cauldron of Fiery Fire runs 2 hours 5 minutes with one 15-minute intermission at Vineyard Theatre until December 7 in its first extension. https://vineyardtheatre.org/showsevents/

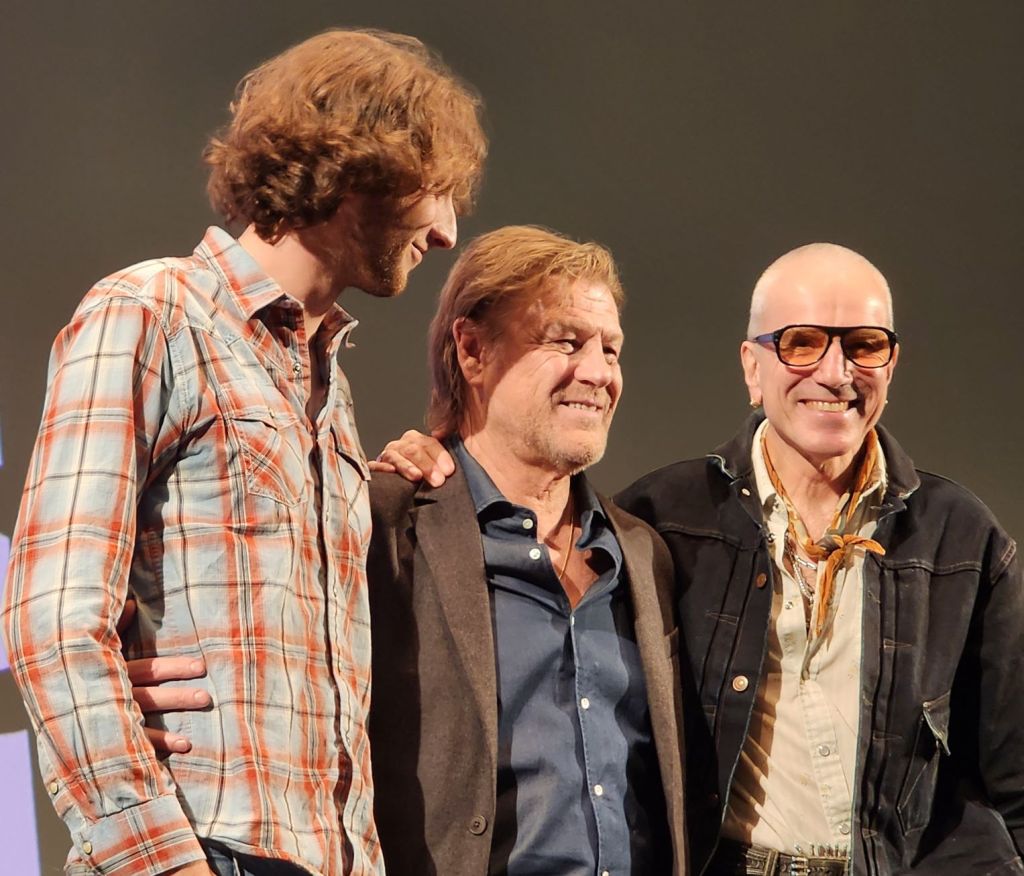

‘Anemone’ @NYFF Brings Daniel Day-Lewis’ Sensational Return

Supporting his son Ronan Day-Lewis’ direction in a collaborative writing effort, Daniel Day-Lewis comes out of his 8-year retirement to present a bravura performance in Anemone. The film, his son’s directing debut, screened as a World Premier in the Spotlight section of the 63rd NYFF.

Ronan Day-Lewis’ feature resonates with power. First, the eye-popping natural landscapes captured by Ben Fordesman’s cinematography stun with their heightened visual imagery. Secondly, the striking, archetypal symbols illuminate redemptive themes. Day-Lewis uses them to suggest sacrifice, faith and love conquer the nihilistic evils visited upon Ray (Daniel Day-Lewis) and ultimately his entire family.

Finally, the emotionally powerful, acute performances, especially by Daniel Day-Lewis’ Ray and Sean Bean’s Jem, help to create riveting and memorable cinema.

The title of the film derives from the anemone flower’s symbolic, varied meanings. For example, one iteration relates to Greek mythology in the story of Aphrodite, whose mourning tears, shed after her lover Adonis’ death and loss, fell on the ground and blossomed into anemones. Also referenced as “windflowers,” anemone petals open in spring and are scattered on the wind. Possibly representing purity, innocence, honesty and new beginnings, the film’s white anemones grow abundantly in the woodland setting where reclusive Ray makes his home in a Northern England forest.

In a rustic, simplistic hermit-like retreat Ray lives in self-isolation, alienated from his family. Then one day, his brother Jem, prompted by his wife Nessa (Samantha Morton), mysteriously arrives. The director focuses on the action of his arrival withholding identities. Gradually through the dialogue and the rough interactions, heavy with paced, long silences, we discover answers to the mysteries of the estranged family. Furthermore, we learn the characters’ tragic underpinnings caused by searing events from the past. Finally we understand their motivations and close bonds despite the estrangement. By the conclusion family restoration and reconciliation begins.

Unspooling the backstory slowly, the director requires the audience’s patience. Selectively, he releases Ray’s emotional outbursts. These reveal his decades long internal conflict with himself, for not standing up to the perpetrators of his victimization. Neither Jem nor Nessa (Samantha Morton), Ray’s former girlfriend who Jem married after Ray abandoned her and their son, know his secrets. However, the slow revelations of abuse spill out of Ray, as Jem lives with him and endures his ill treatment and rage.

Each brief teasing out of pain-laced information that Jay spews impacts Jem. Because Jem receives strength and understanding from his faith, he puts up with Ray. Indeed, the various segments of Jay’s story seem structured as turning points. Each moves us deeper into Jay’s soul and Jem’s acceptance. Cleverly, by listening to his brother and encouraging him to speak, Jem breaks down Ray’s resistance.

Ray and Jem’s emotional releases trigger and manipulate each other. Once set off, the revelations full of anguish and subtext fall in slow motion like dominoes. Then, climactic sequences augment to an explosive series of events. One, a treacherous wind and hail storm, represents the subterranean rage and turmoil which all of the characters must expurgate before they can heal and come together.

Jay particularly suffered and needs healing. Throughout his life the patriarchal institutions he trusted betrayed and abused him. From his home life (his father), to the church (a cleric), and the military (his immediate superiors), emotional blows attack his soul and psyche. Also, the military makes an example of him. Not only was the abuse unjustified and misunderstood, the perpetrators covered it up and forced his silence. The cruel, forced complicity makes his life a misery in a perpetuating cycle of guilt and shame.

As a result, because Jay’s self-loathing pushes him deeper within his pain, he can’t discuss what happened with his family or anyone else. Of course, he refuses to get help in therapy. Instead, he escapes into nature for solace and peace. The society’s corruptions and his family’s still embracing the institutions that abused him stoke his anger and enmity.

Neglecting his brother Jem, Nessa and his son Brian, who is grown and needs him, Jay perpetrates a psychological violence on them. None of them understand Jay’s abandonment. Sadly, Ray’s absence and rejection shape Brian’s life. Embittered and violent, he endangers himself and others.

How Day-Lewis achieves Ray’s epiphany through Jem’s love occurs in an indirect line of storytelling, through Ray’s monologues and the edgy dialogue between Jem and Ray. By alternating scenes of Nessa and Brian in the city with the brothers in the forest, we realize that time is of the essence. Jem must convince Ray to return to their home to make amends with his son Brian as soon as possible because of a looming threat.

Ultimately, the slow movement in the beginning dialogue could have been speeded up with a trimming of the silences. However, Day-Lewis purposes the quiet between the brothers for a reason whether critics or audience members “get it” or not. The silences reveal an other-worldly, telepathic bond between the brothers. Likewise, on another level Ray’s son Brian connects with his father spiritually, though they are miles away. The director underscores this through Nessa who understands both father and son need each other. Nessa encourages Jem to bring Ray home to Brian. Day-Lewis also uses symbolic visual imagery to suggest the spiritual bond between father and son.

In Anemone, the themes run deep, as the filmmakers explore how love covers a multitude of hurts and wrongdoings. Anemone releases in wider expansion on October 10th in select theaters. For its 63rd New York Film Festival announcement go to https://www.filmlinc.org/nyff/films/anemone/

‘The Weir’ Review: Drinks and Spirits in a remote Irish Pub

Conor McPherson’s The Weir currently in its fourth revival at Irish Repertory Theatre has evolved its significance for our time. It captures the bygone Irish pub culture and isolated countryside, disappeared by hand-held devices, a global economy and social media. Set in an area of Ireland northwest Leitrim or Sligo, five characters exchange ghostly stories as they drink and chase down their desire for community and camaraderie. Directed with precision and fine pacing by Ciarán O’Reilly, The Weir completes the Irish Rep’s summer season closing August 31st.

Charlie Corcoran’s scenic design of the pub with wooden bar, snacks, bottles, a Guinness tap and heating grate is comfortable for anyone to have a few pints and enjoy themselves at a table or nearby bench. With Michael Gottlieb’s warm, inviting lighting that enhances the actors’ storytelling, all the design elements including the music (Drew Levy-sound design), heighten O’Reilly’s vision of an outpost protective of its denizens and a center of good will. It’s perfect for the audience to immerse itself in the intimacy of conversation held in non-threatening surroundings.

On a dark, windy evening the humorous Jack drops in for drinks as a part of his routine after work at the garage that he owns. A local and familiar patron he helps himself to a bottle since he can’t draw a pint of Guinness because the bar’s tap is not working. Brendan (Johnny Hopkins) owner of the pub, house and farm behind it informs him of this sad fact. But no matter. There are plenty of bottles to be had as Jim (John Keating) joins Jack and Brendan for “a small one.” The entertainment for the evening is the entrance of businessman Finbar (Sean Gormley), who will introduce his client Valerie to the “local color,” since she recently purchased Maura Nealon’s old house.

Initially, Jack, Jim and Brendan gossip about the married Finbar’s intentions as he shows up the three bachelors by escorting the young woman to the pub. Jim, caretaker of his mom, and Jack are past their prime in their late 50-60s. Brendan, taken up with his ownership of the pub and farm, is like his friends, lonely and unmarried. None of them are even dating. Thus, the prospect of a young woman coming up from Dublin to their area is worthy of consideration and discussion.

McPherson presents the groundwork, then turns our expectations around and redirects them, after Finbar and Valerie arrive and settle in for drinks. When the conversation turns to folklore, fairy forts and spirits of the area, Valerie’s interest encourages the men to share stories that have spooky underpinnings. Jack begins his monologue about unseen presences knocking on windows and doors, and scaring the residents until the priest blesses the very house that Valerie purchased.

Caught up in his own storytelling which brings a hush over the listeners (and audience), Jack doesn’t realize the import of his story about the Nealon house that Valerie owns. Thankfully, the priest sent the spirits packing. Except there was one last burst of activity when the weir (dam) was being built. Strangely, there were reports of many dead birds on the ground. Then the knocking returned but eventually stopped. Perhaps the fairies showed their displeasure that the weir interfered with their usual bathing place.

Not to be outdone, Finbar shares his ghost story which has the same effect of stirring the emotions of the listeners. Then, it is Jim who tells a shocking, interpretative spiritual sighting. Ironically, Jim’s monologue has a sinister tinge, as he relays what happened when a man appeared and expressed a wish, but couldn’t really have been present because he was dead.

As drinks are purchased after each storyteller’s turn, the belief in the haunting spirits rises, then wanes as doubts take over. After Jim tells his story about the untoward ghost, Valerie goes to the bathroom in Brendan’s house. During her absence Finbar chides all of them. He regrets their stories, especially Jim’s which could have upset Valerie. With Jack’s humorous calling out of Finbar as a hypocrite, they all apologize to each other and drink some more. By this point, the joy of their conversation and good-natured bantering immerses the audience in their community and bond with each other. I could have listened to them talk the rest of the night, thanks to the relaxing, spot-on authenticity of the actors.

Then, once more McPherson shifts the atmosphere and the supernatural becomes more entrenched when Valerie relates her story of an otherworldly presence. Unlike the men’s tales, what she shares is heartfelt, personal, and profound. The others express their sorrow at what happened to her. Importantly, each of the men’s attitudes toward Valerie changes to one of human feeling and concern. Confiding in them to release her grief, they respond with empathy and understanding. Thus, with this human connection, the objectification of the strange young woman accompanied by Finbar at the top of the play vanishes. A new level of feeling has been experienced for the benefit of all present.

After Finbar leaves with Jim, McPherson presents a surprising coup de grâce. Quietly, Jack shares his poignant, personal story of heartbreak, his own haunting by the living. In an intimate emotional release and expression of regret and vulnerability, Jack tells how he loved a woman he would have married, but he let her slip away for no particularly good reason. Mentoring the younger Brendan not to remain alone like he did, Jack says, “There’s not one morning I don’t wake up with her name in the room.”

McPherson’s theme is a giant one. Back in the day when the world was slower, folks sat and talked to each other in community and conviviality. With such an occasion for closeness, they dispelled feelings of isolation and hurt. As they connected, they helped redeem each other, confessing their problems, or swapping mysteries with no certain answers.

As the world modernized, the ebb and flow of the culture changed and became stopped up, controlled by outside forces. Blocked by fewer opportunities to connect, people retreated into themselves. The opportunities to share dried up, redirected by distractions, much as a dam might redirect the ebb and flow of a river and destroy a place where magical fairies once bathed.

McPherson’s terrific, symbolic play in the hands of O’Reilly, the ensemble and creative team is a nod to the “old ways.” It reminds us of the value of gathering around campfires, fireplaces or heating stoves to tell stories. As companions warm themselves, they unfreeze their souls, learn of each other, and break through the deep silences of human suffering to heal.

The Weir runs 1 hour 40 minutes with no intermission at Irish Repertory Theatre (132 West 22nd St). https://irishrep.org/tickets/

‘Babe,’ Theater Review: Marisa Tomei, Rocking Through to the Next Phase

Babe

Can people change? Or do they just flip their perspectives and deceive themselves to believe they’re “evolving?” In the New Group presentation of Babe, written by Jessica Goldberg, directed by Scott Elliott, Abigail (Marisa Tomei), is Gus’ (Arliss Howard), invaluable collaborator in the music industry. The comedy/drama focuses on a number of current issues using Abby and Gus’ relationship as a focal point to explore the landscape of shifting political correctness, power dynamics, generational conflicts, delayed self-actualization, and more. With original music by the trio BETTY, Babe runs approximately 85 minutes with no intermission at the Signature Center until December 22nd.

Treading lightly on Gus’ rocky ground, Abby has been instrumental in maintaining their successful, collegial relationship for thirty-two years, though at a steep, personal price. She hasn’t acknowledged the sacrifice to herself or been inspired to make a change until the confident, twenty-nine year old, Katherine, interviews with Gus, while Abby monitors their conversation and tries to give him clues when to end his political incorrectness. Katherine’s poise and forward attitude develops during the play as the catalyst which ignites a fire that turns into a conflagration between Gus, Abby and Katherine by the conclusion.

Tomei’s astute Abby is sensitive and insightful

Tomei’s astute Abby provides the sensitivity and insight into the zeitgeist that electrifies fans and brings in the gold records, a number of which hang on the walls of Gus’s chic office (sleek, versatile set design by Derek McLane). The producing legend now in his 60s, but fronting his hip, “with-it” ethos in his tight, black pants, chains, stylized beret, and black leather jacket (Jeff Mahshie, costume design), is at “the top of his game,”and on a down-hill slide, indicated by the sensitivity-training Abby references he has had to withstand. We learn it has been ordered by patriarchal, music company head Bob, who also needs to correct himself, but is powerful enough not to. The hope is with Abby’s continual guidance, and the training, Gus’ boorish, self-absorbed, toxic maleness and unrestrained egotism, encouraged at the company by the other men in the past, will refine. Not a chance, as old dogs refuse to learn new tricks.

As groundbreaking, protective and vital as Abby has been to Gus, the two A & R reps, who have discovered and fashioned some of the most successful solo artists in the business, are not equal in stature, success or monetary rewards. Abby’s discovery of Kat Wonder epitomizes these disparities between her boss Gus, and her, as his second. The only woman in the company for years, Abby suffered through the vulgar and abusive patriarchy, a fact she admits late in the play. To her credit, she managed to gain Gus and the others’ respect and esteem. They keep her around because, as Gus suggests, they think she is like them. We learn by degrees that this is because she is silent and as apparently sedate as her bland, grey pants, white top and black jacket. She is unobtrusive and remains professional, the perfect “Girl Friday,” who allows them to “let it all hang out,” without judging their behavior or making them feel like pigs.

Abby is shut out of receiving credit for her sterling efforts

For her pains to participate, Abby didn’t receive credit on any of the Kat Wonder albums, an “invisible” co-producer. Nor did she share in the spoils as Gus did with global residences and a townhouse he forces the staff to meet in at his convenience, instead of the conference room.

However, ignoring Gus as “all that,” Katherine conflicts with his philosophy, his pronouncements, his ideas. If opposites attract, these two are an exception. Gus sees Katherine’s cultural approaches as pretentious and immaterial (vegan he is not). Katherine is gently oppositional as she pitches herself, her education and background. Interestingly, Katherine sees Abby as a hero to admire. In the initial meet-up, Katherine recognizes Abby from a photo Abby appears in with phenom of the time, “Kat Wonder” at CBGB.Admiring Abby and fawning over her after the interview, Katherine tells Abby that she has been her inspiration to get into the business and wanted to be her.

As obnoxious as Katherine’s forward presumptuousness is, her confidence and appearance remind Abby of Kat Wonder, whose wild grace and energy haunts her throughout the play. Kat appears in her imagination in flashbacks at varying, crucial turning points, with Gracie McGraw doubling for Kat Wonder. These memories of their time together direct Abby toward self-realization and an eventual confrontation with Gus about his unjust treatment of her. This is obviously a painful realization which Abby eventually allows, despite acknowledging Gus’ platonic love, and respect. His concern for her is apparent when he sits with her during a very uncomfortable chemo treatment for her breast cancer.

Katherine visits Abby in an unusual get-together

After Katherine again attempts to rise in the company in another interaction with Gus, she visits Abby at her apartment (McLane’s set design again shines in the transition from Gus’ office to Abby’s apartment and back). They listen to music and Katherine asks Abby probing questions. Then they rock out to music and she dances with Abby, at which point Katherine pushes herself on Abby. Abby is forced to rebuff her because any relationship between them is inappropriate. Nevertheless, this trigger, Goldberg implies, impacts Abby. Abby’s remembrance of her relationship with Kat brings her into a deepening realization of herself because of her experiences, including feeling responsible for Kat Wonder’s death, and being shut out of the glory of notoriety as producer who discovered grunge-rocker Kat.

Abby’s realizations about what she has allowed emotionally, which may have contributed to her physical illness and stress, coupled with a twist that Katherine generates, bring about a surprising conclusion. However, Abby’s response to the final events is the most crucial and important. Maybe it is possible in one’s middle age to forge a new path and become one’s own self-proclaimed star.

The ensemble melds with authenticity and flair

The actors convey their characters with spot-on authenticity, aptly shepherded by Elliot’s direction. Arliss Howard manages to break through Gus’ character with a winning charm and matter-of-factness, which throws dust in the audience’s eyes, even after Katherine corrects his back-handed compliment of her as a “smart girl.” Marisa Tomei as Abby is imminently watchable and versatile as she moves from quiet restraint, to the throes of physical and emotional suffering. The development and culmination of her rage and satisfying expression of it in rocking-out with Kat Wonder is powerful especially at the conclusion. As always Tomei gives it the fullness of her talent, rounding out the Abby’s humanity despite Goldberg’s thin characterization.

Gracie McGraw’s portrayal of Kat Wonder, the 1990s grunge rocker who embodied “centuries of female rage,” before she self-destructed is too brief, perhaps. Much is suggested in Kat’s and Abby’s relationship, but remains opaque. However, we do get to see McGraw’s Kat cut loose. And the memory is so alive and vibrant, it encourages Tomei’s Abby to be her own rock-star, wailing out her repressed rage by the conclusion of Babe. And the women in the audience wail with her, especially now, after the election.

Babe covers many interesting points. To what extent has music been egregiously shaped by the current technologies? What damage has been done as the music and entertainment industry, hypocritically shaped by cultural politics, only creates artificial boundaries on the surface that don’t penetrate the noxious back room parties and behaviors which have given rise to worse abuses? Another issue defines the difficulties of compromise and corruption which spans every institution, every industry. To be a part, one has to be complicit, and then be satisfied with less of a reward because others hold the power and money and make up the rules. Babe scratches the surface and leaves food for thought. The performances are noteworthy and should be seen.

Kudos to the creatives not mentioned before which include Cha See (lighting design), Jessica Paz (sound design), Matthew Armentrout (hair and wig design), and not enough of BETTY’S original music.

Babe runs 85 minutes with no intermission at the Signature Center.

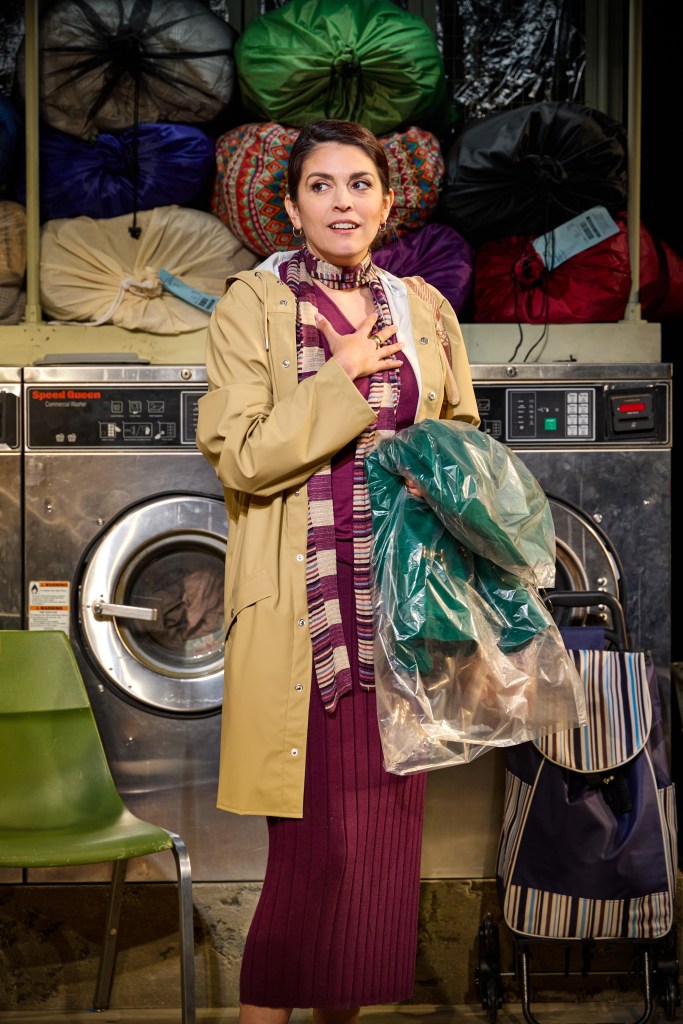

‘Brooklyn Laundry’ a Soap-diluted Rom-com That Avoids the Soul-dirt

John Patrick Shanley’s Brooklyn Laundry, currently at MTC Stage 1 never quite elucidates trenchant themes though it might have with further character development. The 80 minute play, also directed by Shanley, currently runs at New York City Center Stage 1 until April 14th.

Starring Cecily Strong (“Saturday Night Live”), and David Zayas (“Dexter’), as the principal couple who meet in a drop-off laundry in Bushwick, Brooklyn, in Brooklyn Laundry Shanley presents two individuals who become involved with each other as a result of desperation, depression and loneliness. Also, they are between partners and have not been involved in a successful relationship ever.

The Meet-Up

Laundry owner Owen (the lively Zayas), engages in light conversation with Strong’s Fran as the play opens. She is an on again off again customer, whose boyfriend left. Fran admits later in the scene that she is self-conscious about the fact that she can barely scrounge enough laundry to drop off for one load. When she was with her boyfriend, the bag weighed thirty-eight pounds; they did their laundry together. Owen, who Fran reminds that he owes her credit for losing a bag of her laundry 6 months prior, acknowledges that her lost laundry is a mystery. He has been giving her credit, though she complains that it doesn’t cover the price of replacing the missing items.

As they chit chat, Owen notes her “gloomy” nature to jostle her out of it. He tells her she reminds him of his fiance, who was “smart, one inch from terrific, but gloomy.” Fran disputes his label about her and suggests reality has brought issues into her life, and it isn’t without reason that her situation doesn’t make her the sunshine kid.

Owen discusses the necessity for positivity and an uplifted attitude, sharing his recent life story. He became the owner of three laundries, after a car accident settlement and lawsuit against his 9 to 5 boss who unfairly fired him. Assured that he has answers for her life in the face of her wishing she could have a car accident and be so lucky for monetary settlements, he takes a leap of faith. With apparent confidence he asks her to dinner. Fran suggests she will after she returns from a family visit in Pennsylvania.

Shanley has established the ground rules for these two individuals from different backgrounds with little in common, who make a connection simply by being present together and willing it. From this initial spark, Shanley takes us on a journey of how unlikely singles Fran and Owen fall in love because of need.

Reality’s Gloom and Fran’s Escape

In the next segment, we understand why Fran is depressed when she visits her sister Trish (Florencia Lozano), who is ill with cancer, loopy on meds and lying in bed mostly unconscious. After her visit with Trish, Fran goes on her date with Owen high on magic mushrooms. She offers some to Owen and after a while he catches up to her. Together they experience the beauty of the lights and atmosphere of romanticism and their conversation intensifies.

On a sub rosa level, Fran introduces the mushrooms into the situation because she wants to escape thoughts about her dying sister. She chooses to live in a lovely, seductive place with Owen. She doesn’t share her Trish reality with him for fear it will drive him away. So she suppresses her emotions to suit his needs to be positive and upbeat. She puts aside her gloominess, despite the fact that complications with Trish abound and she has less than a month to live.

The mushrooms encourage their intimacy and Fran helps Owen conquer his sexual problems that happened as a result of his car accident, problems which turned off his former girlfriend who dumped him as a result of his poor performance. Interestingly, Owen is honest about a very sensitive subject with Fran and of course she helps him. On the other hand, Fran is dishonest with Owen because he set the parameters that she feels she must adhere to to be with him: no gloom. Thus, Fran and Owen become closer after their first date of intimacy, and after three weeks, theirs is a budding love.

However, another jolt of reality intrudes and slams Fran in her “honesty” with Owen. Fran’s other sister Susie (Andrea Syglowski is always spot-on), stops by to collect Fran so together they will make arrangements for Trish’s imminent death. Fran refuses to go with Susie initially. She fears if she leaves Owen to spend time with family, she will lose the momentum of their relationship and he will dump her for someone else. With lies of omission, she lives in her own dream that she can spin along her affair with Owen without introducing the ugly realities about Trish dying.

The argument that ensues between Strong’s Fran and Sydlowski’s Susie about whether to visit Trish before she dies is beautifully paced and authentically threaded by both actors. During their accusations against each other, we learn how high the stakes are for Fran, who has never been married and has been the hand maiden to her two divorced sisters and their relationships with their loser husbands. We realize why she elected to escape to a love relationship with someone off beat which she clings to so she doesn’t have to face the doom and sadness of her life. Because Owen doesn’t appreciate negativity, his wants prevent her from spilling her emotions to him. Ironically, she is cutting off a valuable part of herself because she fears he only wants “happy, happy.”

Spoiler Alert

Then Susie levels with Fran about why she didn’t accompany her to see Trish the last visit. Susie is dying of pancreatic cancer.

With charming facility Owen cleaned off the “gloomies” from Fran’s plate to no avail. Susie’s horrible news slams Fran with a triple portion of gloom. Not only must she confront Trish’s impending death and the consequences of its impact on Trish’s young child, Taylor, she must confront the consequences of Susie’s dire prognosis. Fran’s doom and gloom lifted for three weeks by Owen will be a permanent fixture in her life. Additionally, guardianship of her sisters’ three children and their financial custodianship falls to her as their closest living relative. Will Owen want to take on a woman with three kids especially since he confessed he only wants his own child and isn’t looking for huge bills to pay for the upkeep of children who aren’t his?

The strength of Brooklyn Laundry is in how Shanley weaves the events, to back Fran into a corner delivering reality’s blows to her life, while showing her desperation to escape her circumstances by not sharing the truth with Owen. Eventually, her own obfuscations come back to haunt her. When Susie tells her about her cancer, Fran wakes up and stops moving in her imagined dream. She assures Susie she will act responsibly. Shanley’s characterization of Fran reveals her nobility, self-sacrifice and integrity in honoring her sisters by raising their children. She has made up her mind and whatever Owen does is up to him, take it or leave it. Fran puts family first.

The Last 10 Minutes

The last ten minutes of Brooklyn Laundry are the most dynamic because we note the inner struggles of the characters as they deal with hidden truths. Fran confronts Owen who stopped answering her calls. Though he portrays himself as the victim and ignores her comments that he ghosted her, something he promised he would never do, eventually, he is forced to put his pride aside. They both realize what they will lose without each other, and they are able to accept with humility that they care.

Shanley perhaps misses important dramatic moments by having the characters report their reactions after the fact to each other, instead of establishing a few scenes that are immediate, confrontational and a dynamic build up with irony. Instead, he writes one scene of alive confrontation and saves it for the very end. It is then that Fran’s serenity with reality shines and Owen reveals himself to be a typical male, more full of himself than he needs to be. However, after Fran walks out of his life to live in Pennsylvania, he realizes his mistake. The play’s conclusion falls into place with a few humorous surprises to satisfy audiences.

Kudos to the involved three-set scenic design of Santo Loquasto, Suzy Benzinger’s costume design, Brian MacDevitt’s lighting design. MacDevitt presents the magical fairy land lighting of the restaurant scene perfectly. Additional kudos goes to original music and sound design by John Gromada.

Brooklyn Laundry is facile and enjoyable thanks to the excellent acting ensemble. Shanley’s rhythms about loss, need and taking risks without ego are imminently human and recognizable.

Brooklyn Laundry with no intermission is in a limited engagement until April 14th. New York City Center MTC Stage 1, 131 West 55th St between 6th and 7th. manhattantheatreclub.com.