Blog Archives

‘Smash,’ Fabulous Send up of a Musical Comedy About Marilyn Monroe

Smash

Chatting with two theater critics beforehand, who referenced the 2012 NBC television series also called “Smash,” I was initially distracted. The TV series set in the present revolved around two aspiring actresses who compete for the role of Marilyn Monroe in a Broadway-bound musical called “Bombshell,” about Marilyn Monroe. Apparently, the TV series which devolved into a musical soap opera, lasted two seasons then was cancelled. Since I never saw the series, I tried to ignore the critics’ comments. I fastened my seat belt and settled in to watch the revamped production in its current run at the Imperial Theatre with tickets on sale through January 4, 2026.

I had no reason to”fasten my seat belt.” Smash is a winner. Superbly directed by Susan Stroman, a master of comedic pacing and the quick flip of one-liners, Smash is a resounding must see, retaining little of the TV show with the same title. I adored it and belly-laughed my way through the end of Act I and throughout Act II.

Into the first act when Ivy Lynn (the grand Robyn Hurder), introduces her Method Acting coach, Susan Proctor (the wonderfully funny Kristine Nielsen channeling Actors Studio Paula Strasberg), I embraced the sharp, ironic and often hysterical, theater-referenced send-ups. The book by Bob Martin & Rick Elice is clever and riotous, pushing the true angst of putting on a big Broadway musical and spending millions to make it a success. Martin and Elice’s jokes and the characterizations of Nielsen’s Susan Proctor and director Nigel, the LOL on point Brooks Ashmanskas (The Prom), who tweaks the gay tropes with aplomb, work. Both actors’ portrayals lift the arc of the musical’s development with irresistible comedic riffs shepherded by Stroman’s precise timing.

The music had me at the opening with the vibrant fantasy number, “Let Me Be Your Star,” sung by Robyn Hurder, whose lustrous voice introduces Marilyn and her fandom which the creators attempt to envision with fully costumed performers singing for their musical, “Bombshell,” the Marilyn Monroe story. Then, the scene shifts to the rehearsal room where we meet the creative team who imagined the previous number and scene. Ashmanskas’ director/choreographer Nigel humorously bumps heads with writer/lyricist/composer-husband and wife team Tracy (Krysta Rodriguez) and Jerry (John Behlmann).

Also present, is his associate director and Nigel’s right arm, the golden voiced Chloe (Bella Coppola). She runs interference and puts out fires, even covering for Ivy Lynn and understudy Karen (Caroline Bowman), during an audience invited presentation. Why Ivy Lynn and Karen can’t go on is hysterical.

The music by Marc Shaiman, lyrics by Scott Wittman and Marc Shaiman, and the choreography by Joshua Bergasse are upgraded from the TV series with a curated selection of songs to align with the comedic flourishes. The musical numbers and dances cohere perfectly because the performers rehearse for their show “Bombshell.” With music supervision by Stephen Oremus, an 18-piece orchestra charges the score with vibrant dynamism. Featured are some of Shaiman’s brassiest tunes, orchestrated by Doug Besterman. Lyricist Wittman seals the humor and advances the plot. All provide grist for Bergasse’s choreography. Hurder manages this seamlessly as she sings, breathes heartily and dances while the male dancers whip and flip Ivy as Marilyn around. Of course, all smile with effortless abandon despite their exertions.

Importantly, Martin and Elice’s book sports farcical, riotous moments. These build to a wonderful crescendo by the conclusion. By then we realize we’ve come full circle and have been delighted by this send up of the wild ride these creatives went through to induce the belly-laughing “flop,” we’re standing, cheering and applauding. It’s the perfect ironic twist.

Indeed, once the audience understands the difference in tone from the TV series, largely due to Nielsen’s Proctor (she’s dressed in black mourning {Marilyn?} from head to foot), and Ashmanskas’ Nigel, Smash becomes a runaway train of hilarity. This comedy about unintentionally making a musical flop (unlike the willful intent in The Producers), smartly walks the balance beam by giving the insider’s scoop why “Bombshell” probably never finds a home on Broadway. One of the reasons involves too many chefs trying to make a Michelin starred dish without really understanding how the ingredients meld.

Nielsen’s Proctor dominates Ivy Lynn to the point of transforming the sweet, beloved actress into the “difficult,” “tortured soul” of diva Marilyn. The extremes this conceit reaches is beyond funny and grounded in truth which makes it even more humorous. Without giving too much away, there is a marvelous unity of the book, music and Hurder’s performance encouraged by Nielsen’s Marilyn-obsessed Proctor. We see before our eyes the gradual fulfillment (Proctor’s intention), of “Marilyn,” from superficial, bubbly, sparkly “sex bomb,” to soulful, deep, living woman produced by “the Method.” Of course to accomplish this, the entire production as a comedy is upended. This drives Nigel, Tracy and Jerry into sustained panic mode, exasperation and further LOL behavior especially in their self-soothing coping behaviors.

Furthermore, Producer Anita (Jacqueline B. Arnold), forced to hire Gen Z internet influencer publicist Scott (Nicholas Matos), to get $1 million of the $20 million needed to fund the show, mistakenly allows him to get out of hand, inviting over 100 influencers to Chloe’s serendipitous cover performance. The influencers create tremendous controversy which is what Broadway musical producers usually give their “eye teeth” for. Publicity sells tickets. But this controversy “backfires” and creates such an updraft, even Chloe can’t put the conflagration out. The hullabaloo is uproarious.

The arguments created by the influencers and their followers (in a very funny segment thanks to S. Katy Tucker’s video and projection design), cause huge problems among the actresses and forward momentum of “Bombshell.” Karen, Ivy Lynn’s friend and long time understudy, who has been waiting for a break for six years, watches Chloe become famous overnight for her cover. Diva Ivy Lynn who IS Marilyn is so “over the moon” jealous and threatened, she breaks up her close friendship with Karen and turns on cast and creatives, prompted by Nielsen’s Proctor who keeps up Ivy Lynn’s energy with a weird combination of mysterious white pills and even weirder “Method” tips.

Thus, the musical “Bombshell” becomes exactly what the creatives swore it would never become and someone must be sacrificed. Who stays and who leaves and what happens turns into some of the finest comedy about how not to put on a Broadway flop. Just great!

Smash is too much fun not to see. What makes it a hit are the superb singing, acting and dancing by an expert ensemble, phenomenal direction and the coherence of every element from book to music, to the choreography to the technical aspects. Finally, the show’s nonsensical sensible is brilliant.

Praise goes to those not mentioned before with Beowulf Boritt’s flexible, appropriate set design, Ken Billington’s “smashing” lighting design, Brian Ronan’s sound design, Charles G. LaPointe’s hair and wig design, and John Delude II’s makeup design.

Smash runs 2 hours, 30 minutes, including one intermission at the Imperial Theatre (249 West 45th street). https://smashbroadway.com/

Susan Stroman Interviewed by Sharon Washington, a LPTW Event

On Friday, November 17, the League of Professional Theatre Women held an interview of an icon in the theater, Susan Stroman. The event was part of The Oral History Project which is held at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center. The venue was the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center/Bruno Walter Auditorium.

Currently produced for the League by producer and director Ludovica Villar-Hauser, The Oral History Project was founded and produced for 26 years by the late Betty L. Corwin. The interview of Susan Stroman by friend and colleague Sharon Washington was video taped and will be archived in the collections of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center.

How Sharon Washington and Susan Stroman met

After comments by President Ludovica Villar-Hauser, and introductions, Sharon Washington (check out her credits and work on https://iamsharonwashington.com/), began by sharing the story of how she came to first meet Susan Stroman in 2009. At the time, Washington’s agent suggested she audition for a part in a musical, though Washington was a dramatic actress. When Washington posed that she hadn’t been in any musicals, her agent reassured her that in this one, she wouldn’t have to sing, dance or speak. Ironically, Washington questioned why she would even consider such a part. However, her agent countered that it would be directed by Susan Stroman.

Thus, Washington and Stroman collaborated on the 12 times Tony nominated Scottsboro Boys. The musical went on to win the Evening Standard Award for Best Musical in the UK. Though the production didn’t win any Tonys, Washington emphasized that then and now, Stroman’s process is exhilarating.

Specifically, Stroman creates a safe room that is caring. Washington and the other cast members felt so comfortable that they could work freely. Washington pointed out during the interview that Stroman imbues a quality of trust to be a creative collaborator. In her safe space one can try things out and make suggestions. This artistry of bringing out the best in the cast and creative team has brought Stroman accolades and forever friends. Sharon Washington is one of them.

Susan Stroman is a theater Icon

Susan Stroman (Director/Choreographer), is a five-time Tony Award-winning director and choreographer. She has won Olivier, Drama Desk, Outer Critics Circle, Lucille Lortel Awards. Also, for her choreography, she has won a record number (six) of Astaire Awards. Recently, she directed and choreographed the new musical New York, New York, which was nominated for nine Tony Awards and which won Best Scenic Design for a Musical (Beowulf Boritt). The music was by John Kander, lyrics by Fred Ebb and Lin Manuel Miranda, and a book by David Thompson and friend Sharon Washington.

In other recent work, she directed the hysterical, LOL new play POTUS: Or, Behind Every Great Dumbass Are Seven Women Trying to Keep Him Alive. And this season in London’s West End, she directed and choreographed the revival of Crazy for You at the Gillian Lynne Theatre.

Past exceptional productions include her direction and choreography for The Producers (12 Tony Awards including Best Direction and Best Choreography). She co-created, directed and choreographed the Tony Award-winning musical Contact for Lincoln Center Theater. She received a 2003 Emmy Award for Live from Lincoln Center. Broadway credits include Oklahoma!, Show Boat, Prince of Broadway, Bullets Over Broadway, Big Fish, Young Frankenstein, The Music Man and others. Her Off-Broadway Credits include The Beast in the Jungle, Dot, and Flora the Red Menace to name a few.

Stroman has experience with ballet and opera

She garnered additional theater credits and to these add ballet and opera which include The Merry Widow (Metropolitan Opera); Double Feature, and For the Love of Duke (New York City Ballet). She received four Golden Globe nominations for her direction and choreography for The Producers: The Movie Musical. Additionally, she is the recipient of the George Abbott Award for Lifetime Achievement in the American Theater, and an inductee of the Theater Hall of Fame in New York City. For her complete list of accomplishments, credits and awards, go to www.SusanStroman.com

After Washington and Stroman discussed her beginnings growing up in Delaware in a house of music, where she danced and was in dancing school, she would always create dances when her father played the piano. She grew up appreciating her father’s storytelling and musical talent. She majored in English at the University of Delaware and was attracted to story telling and its different forms which, of course, included music and dance. She mentioned that her family would watch movie musicals together on their sofa, and as she watched, she intuited the synchronicity between the dance and the music and the feeling it created. Storytelling through the dance came easily to her because of her parents and their appreciation of musicals, music, movement and how dancing conveyed the story.

Choreography helps to move the plot forward

For Stroman, today, especially with the virtual media environment, choreography is imperative for moving the plot and story forward in immediacy. The audience wants the story to move forward constantly, which can be accomplished with choreography transitioning the turning points so the events have a forward momentum. In recognizing the importance of the staging and the dance, every corner of the stage must be considered. There is no empty part of the stage that doesn’t have the element of storytelling through dance, music and dialogue.

It is a testament to Stroman’s ability to continually provide fascinating visuals, color and movement so entrancing to audiences, who love her work, if sometimes critics don’t fully understand or appreciate the genius she displays. Indeed, with the stage beginning as a writer begins with a blank page, Stroman thinks profoundly about every dancer, every performer, every musical note, every word of dialogue and of course all the elements in the story (Aristotle’s poetics).

For my mind, her works should be studied in musical theater classes in universities for their immediacy, their vibrance, their emotional grist and their coherence as they synchronize elements of scenic design, costume design, and hair and wig design, lighting, sound, to effect the beauty, sorrow, majesty of the story being told.

The film The Sound of Music was an influence

Stroman emphasized that she and her brother saw The Sound of Music together and it impacted her understanding. She stated, “I was blown away by that movie. I guess I was twelve.” She couldn’t believe the story that was being told and how important the story was, realizing it could be something which is really profound. Stroman followed with the idea that she visualizes music with a story following along. Additionally, she imagines how the dancers would be dancing. Immediately, her “brain begins to spin about what story is being told through the music, the instrumentation and the orchestrations.”

When Stroman puts a show together, she “works very much with the show’s composer and arranger,” of how to open up the music. She manipulates the time signature of the music to help represent the emotion she wants the actors to play and to move forward the momentum of the story. She does a lot of research on every musical. This might include the history of the decade, the geographical area, the setting. She immerses herself in research and thinks extensively about the characters. This helps to inform how she choreographs the music.

Working with performers is about collaborating in a safe space.

Working with actors is about collaborating in a safe space. First, comes the research. Then comes the time and effort put into using what has been learned. Washington attested to Stroman’s being there early before everyone else, and staying late after everyone was gone. Stroman works extensively with her musical partners. Additionally, she is aware of the actor’s process. Each have their own process. Some pick up elements very quickly and others don’t. It is a balancing act to get all on the same page and not make them feel inferior.

In making sure all feel comfortable in the learning process, Stroman stays positive and roots for her actors, wanting them to do their best. Getting the performers to the point of excellence, she has to do her research and be prepared before she ever creates the safe space in the rehearsal room. When they arrive there together, she’s worked through almost the entire show. However, part of creation and allowing the cast to feel comfortable, she doesn’t share all of what she knows. She wants them “to feel free” and be creative and “feel a part of it.” She’s also inspired by the performers who come up with their own creative suggestions. She allows for actors and dancers’ agency, encouraging them to try something different.

Stroman collaborated with Washington during the production, Dot

Stroman shared a moment in Dot where Sharon Washington’s character had extensive monologues and she gave her the stage action of cooking eggs. Stroman had Washington pace the dialogue with cooking eggs so that she finished every time on a particular word. Though Washington was skeptical at first, she become so attuned, that the timing was perfect. With Stroman’s encouragement, she finished when the eggs were done and landed precisely on the designated “word” in the monologue. Both Stroman and Washington discussed the wonder of creating something that didn’t exist before. Considering all the people that collaborated in the creation, the artistry of that collaboration to present something amazing is miraculous.

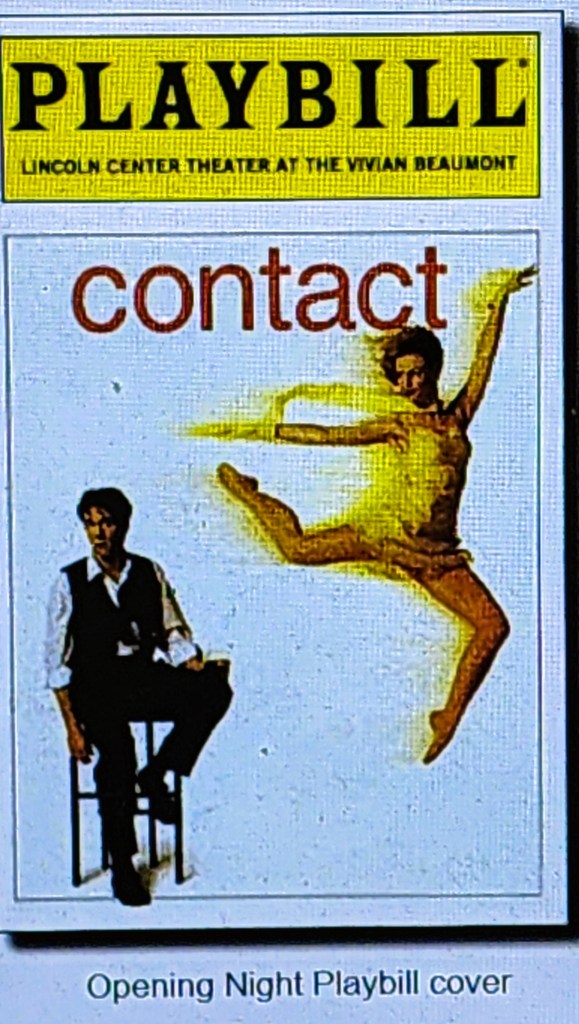

Stroman discussed how the ideas for various scripts or stories come from various places. The seminal idea for the show Contact came surprisingly with the image of the girl in the yellow dress. Stroman discussed that she was in a bar at one in the morning, and in a bar where all the New Yorkers wore black. And “in walked this girl with a yellow dress which I thought was quite bold for one in the morning.” Stroman described the girl’s action, “She would step forward when she wanted to dance with somebody, and then she would retreat back when she was done with them.” According to Stroman, she was an amazing dancer and she was only there to dance. Stroman watched her dance with various men. Then she disappeared into the night.

The girl with the yellow dress becomes Contact

Around two weeks later at Lincoln Center, Stroman was approached about having ideas. She said, “You know, I think I have an idea.” And from then on, the story of the girl in the yellow dress took flight, bringing in all the elements of music, dance, and storyline. That’s how Contact came into existence, from a visual and organic, raw experience that stirred Susan Stroman’s imagination. Amazing! Contact ran for three years. Humorously, Stroman discussed how pictures of the “girl in the yellow dress” were on busses and billboards and she was thinking the girl would come forward and say something. She never did.

Stroman shared another story about the time she met with Mel Brooks. She was working on A Christmas Carol when she received a call to meet with Mel Brooks. Familiar with his work, she wondered what he wanted to talk to her about. There was a knock at the door. And when she opened it, he started singing, “That face, that face…” and he danced down Stroman’s long hallway, then jumped up on her sofa and said, “Hello! I’m Mel Brooks.” Stroman shared that she didn’t know what would happen. She thought, “But whatever it is, it’s going to be a great adventure.” Indeed, the experience was, “the adventure of a lifetime.”

Regarding working with Mel Brooks, Stroman suggested that she learned from him, collaborating and observing. Of course, it was a new art form for him, so he was flexible and learned from Stroman’s theatrical experiences and process of working. It appears they developed a mutual admiration society.

Facing obstacles as a woman

Washington asked about the obstacles Stroman faced as a women. When Stroman got in the business, she stated, “It really was male dominated.” And she mentioned that it has only been in the last fifteen years that there have been women directors. However, she was not certain about “why that is or was.” When she started, she wanted people to believe, “In the art of what I was doing.” She didn’t dress up. She wore a baseball cap. At that time there was a pressure to “dress down,” and be “strong, but not too strong.” Stroman felt like she “could do it,” when she came to New York. However, she didn’t know if she would “be allowed to do it.”

In sharing a story to encourage young people or anyone in the business, she suggested “always ask questions.” The worst that can happen is that “they” say “no.” One day she and another actor were throwing out ideas and came up with the idea to approach Cabaret’s Kander and Ebb and ask if they could take one of their shows and direct and choreograph it for Off-Broadway. They were shocked when Kander and Ebb agreed and they took Flora the Red Menace, reworked it and brought it to The Vineyard Theatre.

Critics

Stroman discussed critics. She mentioned that “bad reviews are very hurtful.” She also suggested that women’s work is more harshly criticized than men’s and that the same applied in politics. She referenced her great disappointment that New York, New York didn’t have staying power and closed. They were waiting for the tourists, but they never came. Regarding the collaboration, she enjoyed working with the creative team tremendously. Of course, that made the show not lasting more poignant. The show received positive and negative reviews. Regarding any positive reviews received over the years, Stroman quipped, “The good reviews are never good enough.” And when there’s a great review, “You think, well, why didn’t they talk about that?” You just “have to feel good about what you are creating,” she insisted.

In discussing mentorship Sharon Washington suggested Stroman is very gracious and lets everyone participate. With every show she does, she usually has “A young observer who comes on the show and they get to be there for the whole process.” She said, “It’s important to be in the room where it happens.” Young people learn best when they see the process unfolding and join in it, participating whenever it is feasible. They learn, then, that it’s a collaboration. As the team works together, the director coheres with all the designers. It is the director, who has a clear vision of what the production should be. Then, the director shepherds the creatives and negotiates through and around the various egos.

For more on Susan Stroman https://www.susanstroman.com/ or Sharon Washington https://iamsharonwashington.com/ go to their websites. For a video of the interview, visit the New York Library for the Performing Arts archive in person.

The League of Professional Theatre Women is a membership organization for professional theatre women representing a diversity of identities, backgrounds, and disciplines. Through its programs and initiatives, it creates community, cultivates leadership, and seeks to increase opportunities and recognition for women in professional theatre. Its mission is to champion, promote, and celebrate the voices, presence and visibility of women theatre professionals and to advocate for parity and recognition for women in theatre across all disciplines.

‘New York, New York’ is a Wow, Manhattanhenge is Here.

Inspired by the titular MGM motion picture written by Earl M. Rauch, the musical New York, New York at the St. James Theatre is an ambitious, updated adaptation from uneven source material. Its spectacular production values guided by the prodigious five-time Tony winner, Susan Stroman, who does double duty with direction and choreography, is set over the course of one year with the four seasons structuring the arc of development in the lives of the characters who want to “be a part of it in old New York,” from the Summer of 1946 through the Summer of 1947. Written by David Thompson, co-written by Sharon Washington with additional lyrics by Lin-Manuel Miranda and music and lyrics by John Kander and Fred Ebb, New York, New York’s music differs from that featured in the titular 1977 Martin Scorsese film.

The noted exceptions are a few songs like “Happy Endings” and two schazam hits sung by Liza Minnelli in the film. Minnelli was initially associated with “New York, New York,” until Liza told Uncle Frank it was his to sing. Afterward, it became a part of every concert, TV show or gig Sinatra starred in. “But The World Goes ‘Round” is singularly Minnelli’s, though others have picked it up and run with it applying their own versions.

With such song classics, the production doesn’t capitalize on their tonal motifs threading intermittently from Act I to Act II more than just once. Instead, saving the best for last, they explode toward the conclusion. At the end Jimmy Doyle’s band (the real orchestra) rises up from the pit, playing “New York, New York” with bravado and glory. By far, the two songs are the richest, most seismic and memorable of the score. Despite who is singing them, they are a pleasure because of their symbolic associations.

The first is New York City’s anthem played as an encouragement around every dooms day disaster the city experienced in recent memory from the Terrorist Attack of 9/11 to the COVID-19 botch job by the twice-impeached former president, when nightly the city came out to applaud healthcare workers and some played Sinatra recordings of the signature song from their balconies. The other lush beauty about the irrevocability of life’s changing turns, highs and lows, is a classic best remembered for Minnelli’s fabulously impassioned rendition.

These songs, in their own right, are like the North Star. “But the World Goes ‘Round” appears to guide the writers to effect a richer, stirring musical about making it in a tough, unforgiving town which necessitates growing a thick skin because regardless, the world will spin, whether one plays the broken-hearted victim as Jimmy Doyle does initially in Act I, or become the heroes of their own myths as do all the characters who serendipitously meet in a Booking agent’s office, then join Doyle to play in a “tired club” in Act II in a reviving number “San Juan Supper Club.” However, reaching success takes a while.

Specifically, the book meanders as it strikes out into different story-lines of immigrants and ethnics, who come to Manhattan to establish their unique voices and become the stars of tomorrow. Problematically, the music, which should lead in a brassy, bold pop style of the latter forties reimagined, follows without the same consequence and heft of the two signature songs we long to hear that show up in full force by the end. The story lines take wayward side directions, straying away from “the heart of it,” making Act I (17 songs) much longer than necessary to spin the characters’ struggles in New York. The central focus becomes redirected. Eventually, it comes back and the lens crystallizes on salient themes, before flitting away to feature another plot-line.

The centrality, which is supposed to be how Jimmy Doyle’s Major Chord Club and musical group comes together, is delayed by scenes of the violinist from Poland and Mrs. Veltri waiting for her solider son to come home. What is represented is the loss and death from the war, a loss which explains why Doyle drinks, is angry and argumentative with those who could help him. He grieves his talented brother dying, while he, the inferior with “flat feet,” serving unheroically behind a desk, feels guilt as the ghostly shadow of his glorious sibling occludes him.

The impact of grieving New Yorkers out from under a cataclysm of the holocaust, which took violinist Alex Mann’s family and the heroic sons of America’s war dead is important, but diluted in the mix of all that is going on. Doyle, Mann (Oliver Prose) and Mrs. Veltri (Emily Skinner) are meant to carry that theme of loss and grieving as one more aspect of the “city that never sleeps,” but the power fades too fast for the audience to fully appreciate it, as the action springs to another scene and character. This is the nature of the city which acknowledges then moves on with forward momentum.

Not all the story-lines need specific scenes for explication. Some either should have been edited to a stark jabbing point with the songs either pumped up and primed, or eliminated. They seem extraneous, done for the sake of inclusiveness, rather than out of a visceral, organic need driving the characters in their forward momentum. Editing might have slimmed down the excess that sometimes dissolves the production’s vitality. Though the writers moved away from the film’s story, to be inclusive and representative in an update, they do feature the relationship between multi-talented musician Doyle (Colton Ryan really picks it up in Act II) and powerhouse singer Francine Evans (Anna Uzele has the creditable voice).

However, the idea of a New York City, where inclusiveness and freedom, born out of anonymity and size, that also has a down side, is not manifested with unique particularity beyond the concepts of struggle and making it. Only Jimmy Doyle’s character is nuanced and shaded with interest to reveal a convincing transformation that is believable, effected beautifully by Colton Ryan.

Despite these problems with the book, Stroman leaps over them creating terrific moments in representing the lifestyle of New York City street scenes. She materializes a pageantry of perfection in staging the dance numbers with delightful framing assists from Borwitt’s scenic design and Billington’s lighting design. These gloriously drive the production, along with the fabulous projection design by Christopher Ash and Beowulf Boritt, which majestically integrates historical photographic blow-ups with the sets (scaffolding erected to look like apartment buildings). New York City in their vision is a treasure to behold back in the day, as they remind us of how we got from then to now. Of course, the heartbreaking projections of the old Pennsylvania Station torn down in contrast with Grand Central Station which we are eternally grateful for Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s crusade to save it, are vital historical references in an ever changing Manhattan.

Stroman choreographs the ensemble with excitement, energy and vibrance. She shepherds the musical’s technical team to strike it hot. They create the atmosphere and stylized beauty of post war New York neighborhoods, synchronizing the scenic design, lighting design and projection design. Along with Donna Zakowska’s stunningly hued costumes pegged to the period, Michael Clifton’s period makeup design, Sabana Majeed’s hair and wig design and Kai Harada’s sound design (I heard every word) these talents manifest Stroman’s concepts of a bustling, charged city hyped up to establish the nation’s new-found prominence after winning WW II in Europe and the Pacific. The city of dreams is once more collecting its dreamers who will sink or swim according to luck and perseverance.

There are many moments in New York, New York I loved. The song “Wine and Peaches,” performed with the ensemble’s tap dance on a foundational iron beam, beautifully set “high in the sky” with the city projected from down below during the ironworkers lunchtime is gobsmacking. It’s a remembrance of the iconic black and white photo of the Empire State Building being erected and ironworkers sitting on the structural beams over 80 + stories up. The song is emblematic of New York City construction workers who are brave, balanced and accustomed to such heights, that they might dance “for the hell of it.” It is also a testament of the tremendous development in the city whose air rights allow buildings to rise taller and taller. Symbolically, visually and musically performed with grace and fun, the number is one of the most memorable and brilliant.

Another moment that is thematically important is the song “Major Chord,” as Jimmy Doyle and friend Tommy Caggiano (Clyde Alves, a fine song and dance man) discuss that “music, money and love” combined in a harmonious chord become what drives a purposeful life for them. In the lead up praise of the city, Tommy’s humorous truism rings clear for New Yorkers when he says, “It’s the greatest social experiment. Everybody lives here and everybody’s natural enemy lives here. And we manage not to kill each other. For the most part.”

To top his comments as New Yorkers are wont to do, Jimmy says, for him, New York City is a “major chord,” and Uzele’s Francine joins in to ask how to find her major chord (music, money, love). Tommy and Jimmy help her find an apartment near Jimmy to start her journey to become a star. Eventually, as fate throws Francine and Jimmy together (more through events he causes) they marry, have ups and downs and reconcile at the “Major Chord,” Jimmy’s successful club which concludes the musical with a resounding and stupendously staged “New York, New York,” sung by Uzele’s Francine.

In Act I, “New York in the Rain” is beautifully sung and staged with colorfully hued umbrellas skipping across the stage, under their own power, and others held by the ensemble who twirl them in uniformity with graceful energy. As Jimmy, Ryan’s “Can You Hear Me?” and “Marry Me,” are appropriately winsome and romantic as Act I concludes with Francine and Jimmy’s relationship sealed in love and marriage.

Act II picks up the forward momentum. Jimmy pushes for his “major chord” in his relationship with Francine, “Along Comes Love” and in the dynamic “San Juan Supper Club” (Ryan, Angel Sigala, John Clay III) which is a rousing, dance number where the musicians we’ve met in Act I come together to form Jimmy’s band which will headline his club Major Chord. In the superb “Quiet Thing,” Ryan’s Doyle shares the preciousness of arriving at his dream, not with great fanfare, but with the inner knowledge of its success, which is the confidence that the dream is the reality. The lyrics and music are Kander and Ebb at their finest, and Ryan delivers a superb, heartfelt slam dunk that any artist can identify with.

As Francine understands that the villain with a smile, Gordon Kendrick (Ben Davis), wants to unrealistically take her, a black woman, out on the road so he can sexually seduce her, Francine affirms what her husband Doyle has told her all along. Kendrick is a hypocritical wolf in a “promoter’s clothing.” She concludes her last song on the radio after Kendrick tells her “she’s finished.” “But the World Goes ‘Round” is Uzele’s home run and Francine’s realization that she must move away from him and join Jimmy at the Major Chord Club.

An incredible and breathtaking encomium to New York City is in one of the final musical numbers “Light” presented by Jesse (John Clay III) and the ensemble. Kudos go to the technical team and Stroman to effect Manhattanhenge through the projections, sets and lighting. It is absolutely magnificent and of course, symbolic that light, love and musical goodness can be in a city that is its own memorial to industry, dreams and aspirations.

Manhattanhenge occurs when the sunset perfectly lines up with the east-west streets on the main street grid in Manhattan. It’s Stonehenge in NYC! Happening twice over a two-day period, on one day you can see the sun in full and on the other day you get a partial view of the sun. Then to encapsulate the “light” in the city that is its own monument, Francine concludes accompanied by Jimmy Doyle’s band with “New York, New York.” And indeed, the show ends in a major chord at Doyle’s Major Chord Club in a beautiful flourish with Uzele singing her heart out as the audience stands with applause dunning the critics who panned the production.

New York, New York is exuberant, complex and bears seeing twice. There is so much happening you’re going to miss something and think the fault is in the production, as I did initially. Stroman is her representative genius. If one goes without expectation, your enjoyment will be immense. Look for the fine performances. Colton Ryan is sensitive and heartfelt especially in Act II and his gradual transformation is exceptional in “Quiet Thing,” and afterward. There’s nothing like knowing one is a success and at home in that confidence. The principals, especially Uzele, Janet Dacal, Ben Davis, Angel Sigala and the others mentioned above have golden voices. All are their own major chords, thanks to the music supervision and arrangements by Sam Davis.

For tickets and times go to the production’s website https://newyorknewyorkbroadway.com/