Blog Archives

‘The Whole of Time,’ Explosive Change in an Intimate Space

Inspired by Tennessee Williams The Glass Menagerie, the intriguing Off Off Broadway production, The Whole of Time by Argentine playwright Romina Paula challenges one to consider the idea of being whole in oneself. Directed and staged by Tony Torn with scenic backdrops by Donald Gallagher, the 22-seat theatrical space of Torn Page seems the perfect place to present a dramatic work that examines the meaning of insularity, affinity, individuality, and isolation within and without intense relationships.

Torn Page, managed by Tony Torn, is in the home of his late parents, the acclaimed actors Rip Torn and Geraldine Page. The three-story townhouse in Chelsea, its central floor, at the top of a wooden staircase that leads into a bar area and further opens into a roomy space to accommodate actors and audience in close proximity, provides the atmosphere and charm associated with artists, theater and film people. The moment I walked up the stairs and into the theatrical space and seating area, I was excited not only by the building’s history, but also by the production that would unfold intensely for an audience less than 10 feet away.

As Paula’s play opens, sister Antonia (Josefina Scaro) and older brother Lorenzo (Lucas Salvagno) enact “Si no te hubieras ido,” (“There’s nothing more difficult than living without you”) by Marco Antonio Solís, the award-winning Mexican singer-songwriter. As Lorenzo passionately sings, Antonia stages him on a chair. A projection of the photo of the singer appears on the wall. A game that they play, Antonia later suggests the singer-songwriter is in jail for murder, a fantasy she constructs to make the interplay between herself and her brother uniquely interesting, as he questions the truth of her assertions.

What is thematic is that the song passionately, romantically uplifts the pain of being separated from one’s lover. Ironically, Antonia alleges that in the case of Solís, the separation is lifelong, for his lover is dead. He killed her himself. Thus, Paula introduces the idea of separation from those one loves with an intriguing sadomasochistic twist: one causes the separation from the beloved, perhaps for the very notion of indulging in a romantic passionate pain of forever longing.

As Lorenzo dresses for a night out with a friend, Antonia asserts fantastic complications about the song which has underlying humor. She says, “Probably in Mexico people forgive or tolerate somebody killing his wife and then selling and making millions of dollars where he sings to the dead woman he misses so much.” Then Antonia continues integrating Frida Kahlo with another fantasy which involves love, death and the pain of loss. Clearly, Antonia’s energy keeps Lorenzo engaged and the nexus of the relationship and emotion between them is far closer than one might anticipate from a brother and sister who otherwise might express sibling rivalry.

However, the object of the rivalry, their mother, Ursula (Ana B. Gabriel), never approaches any level of competition for her children’s affection. Indeed, Antonia bristles at her mother’s insistence she find another path of life rather than to choose to stay at home and not cultivate external social relationships. When Ursula belabors the point, Antonia insists she is happy within herself, and uses her imagination to have experiences, after her mother stumbles at rationalizing Antonia should travel to gain experience.

In her characterization of Antonia, Paula has created an ingenious, autonomous, self-aware and satisfied young woman who is confident and self-possessed. Of the characters in the family, somewhat aligned with Tennessee Williams’ Glass Menagerie only in function, Antonia is the least like her counterpart, sister Laura, who is emotionally broken by her physical handicap. Laura’s physical challenges and her mother’s overbearing, imperious presence have suppressed Laura’s voice and her soul. She has been stifled into shyness and withdrawal.

Conversely, in The Whole of Time, Antonia is her own person, whole and assured, happy to stay at home which she does not view as “isolation” or “withdrawal. Antonia tells Maximiliano (Ben Becher), that unlike him, who must have time from work from which he cuts loose, she doesn’t need to. Antonia says, “I don’t need that contrast to cope with time. I cope with all of my time, the whole of my time, nonstop.”

Thus, where Laura avoids the world, where Jim (the Maximiliano counterpart), and Tom (the Lorenzo counterpart), need a release from work and Lorenzo needs freedom from family, Antonia is contented with every second of her life. Clearly, the opening of the play indicates how she creatively uses her imagination to entertain herself and Lorenzo in fantasies of her own making. As long as he goes along with her in an unusual love dynamic which borders on romantic innocence, all is well for her.

In the scene with Maximiliano, change comes. Antonia interacts with him almost romantically dislocating the dynamic she has established with her brother, who interrupts them and ends any expression of love. Ursula further douses any fires between Maximiliano and Antonia by coming in drunk in a strange reversal.

In the usual construct, siblings vie for their parent’s attentions. In this instance, the interfering, fearful Ursula intends to dislodge Antonia’s love for Lorenzo and vice-versa. Thus, she insists at the top of the play that he tell his sister that he intends to leave. When he doesn’t, knowing the impact it will have on Antonia’s fantastic world and their relationship, later in the play Ursula picks the strategic moment when Maximiliano is present. It is then she reveals Lorenzo is separating from her and Ursula.

Though Lorenzo avers about his intentions, Antonia’s loving, intriguing relationship with her brother is severed. If they are to continue, it will be different. They will no longer be “fantasticks.” Ironically, Antonia’s ability to cope in herself with “the whole of time” has been shattered.

Thus, when Ursula is finished, she has exploded Antonia’s world and Lorenzo’s integral part in it. Despite his protestations that he won’t leave, the separation and loss once acknowledged continues. It is only a matter of “time” until Lorenzo leaves for good. Antonia and Ursula dissolve in tears trying to comfort one another as the opening song “There’s nothing more difficult than living without you” brings the play’s themes about insularity and affinity to a full circle of closure, while Maximiliano witnesses the aftermath.

The ensemble work is excellent and the performances are standouts thanks to Torn’s careful staging and specific shepherding of the actors with skill. The play is a fascinating and disparate take on Williams with countervailing themes that are profound. I especially thought the divergence of the proper Jim to the punk rockin’ Maximiliano was an ironic, humorous update. Jay Ryan’s lighting design adds a wilder perspective, then mutes when reality transfers from the fantastic.

There is no poignant narrator. There are no “tricks in his pocket.” Instead, we see a family, unique, undefinable, needing each other, and conversely, with the exception of Antonia, longing for escape. Any hope of independence from each other is as impossible as is the ability of the characters to leave their own interiors. Though they may separate physically, always, there will be the ties, the fantasies, the bonds, shattered, but still palpable with bits of feeling and emotion.

The Whole of Time at Torn Page. 435 W 22nd St., through February 11th. Delight yourself by seeing this production. You can get tickets online at https://www.eventbrite.com/e/the-whole-of-time-tickets-768576010537

T

‘The Night of the Iguana,’ Theater Review

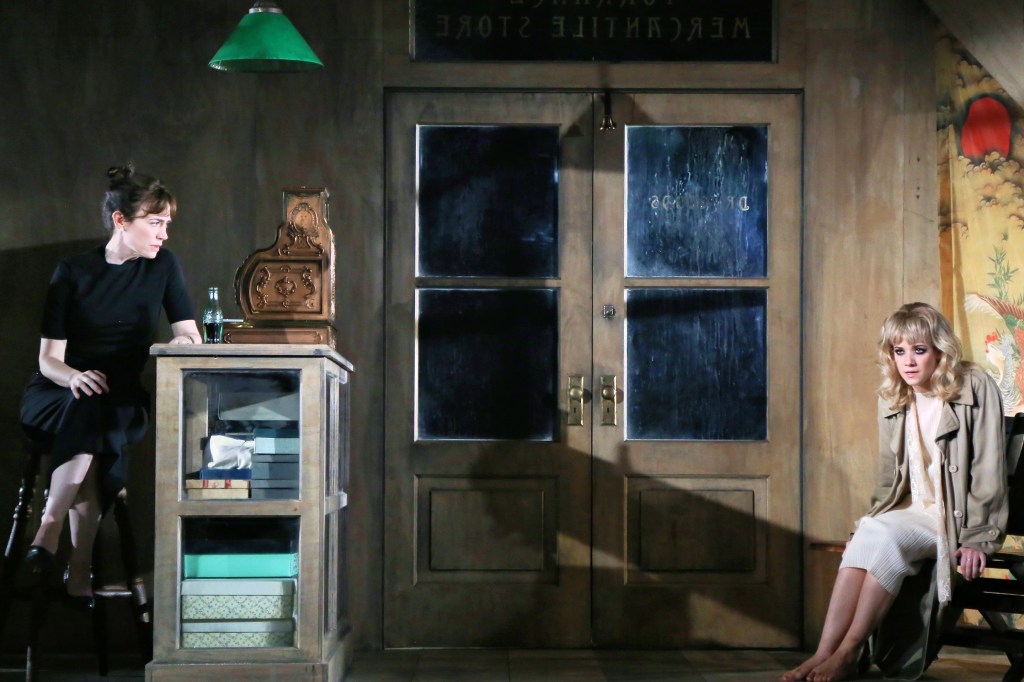

The Night of the Iguana is one of Williams most poetic and lyrical plays with dialogue that touches upon the spiritual and philosophical. On the one hand in Iguana, Williams’ characters are amongst the most broken, isolated and self-destructive of his plays. On the other hand, in their humor, passions and rages, they are among the most identifiable and human. La Femme Theatre Productions’ revival of The Night of the Iguana, directed by Emily Mann, currently at the Pershing Square Signature Center until the 25 of February, expresses many of these elements in a production that is incompletely realized.

The revival, the fourth in 27 years, and sixty-one years after its Broadway premiere, reveals the stickiness of presenting a lengthy, talky play in an age of TikTok, when the average individual’s attention span is about two minutes. Taking that into consideration, Mann tackles Williams’ classic as best as possible with her talented creative team. At times she appears to labor under the task and doesn’t always strike interest with the characters, who otherwise are hell bent on destruction or redemption, and if explored and articulated, are full of dramatic tension and fire.

Beowulf Boritt’s scenic design of the off-kilter, ramshackle inn in the tropical oasis of 1940s Costa Verde, Puerto Barrio, Mexico, and Jeff Croiter’s fine, atmospheric lighting and superbly pageanted sky are the stylized setting where Williams’ broken individuals slide in and out of reality, as they look for respite and a miracle that doesn’t come in the form that they wish. With the period costumes (exception Maxine’s jeans) by Jennifer Von Mayrhauser), we note the best these characters can hope for is a midnight swim in the ocean to distract themselves from their inner turmoil, depression, loneliness, DT’s and brain fever/ The latter are evidence of addiction recoiling, experienced by the play’s anti-hero, “reforming” alcoholic Reverend T. Lawrence Shannon (Tim Daly).

One of the issues in this revival is that the humor, difficult to land with unforced, organic aplomb is missing. At times, the tone is lugubrious. This is so with regard to Tim Daly’s Reverend Shannon, in the scene where he expresses fury with the church in Virginia that locked him out, etc. If done with “righteous indignation,” his rant, with Hannah Jelkes (Jean Lichty), as his “straight person,” could be funny as her response to him elucidates the psychology of what is really going on with the good reverend. It would then be clearer that Shannon is misplaced and just can’t admit he loathes himself and agrees with his congregants who see him as one who despises them and God, an irony. Indeed, is it any wonder they see fit to lock him out of their church?

The ironies, his indignation and Hannah’s droll response are comical and also identify Shannon’s weaknesses and humanity. Unfortunately, the scene loses potency without the balance of humor. Shannon is a fraud to himself and he can’t get out of his own way. Is this a tragedy? If he didn’t realize he was a fraud, it would be. However, he does, thus, Williams’ play should be leading toward a well deserved redemption because of the underlying humor and Shannon’s acceptance that his life is worth saving. In this revival, the redemption merely happens without moment, and the audience remains untouched by it, though impressed that Tim Daly is onstage for most of the play.

The arc of development moves slowly with a few turning points that create the forward momentum toward the conclusion, when Shannon frees an iguana chained at its neck so it won’t be eaten (a metaphor for the wild Shannon that society would destroy). The iguana is released, yet the impact is diminished because the build up is incompletely realized. Little dramatic immediacy occurs between the iguana’s release into freedom and the initial event when Daly’s quaking Reverend Shannon struggles up the walkway of Maxine’s hotel. Daphne Rubin-Vega’s Maxine Faulk and her husband Fred have previously offered escape for Shannon. Now, at the end of nowhere, he goes there to flee the condemnation and oppression meted out by the Texas Baptist ladies he is tour guiding, This slow arc is an obstacle in the play that is difficult to overcome for any director and cast.

In the Act I exposition, we learn that Shannon’s job of last resort as ersatz tour guide has dead-ended him in a final fall from grace. He is soul wrecked and drained after he succumbs to seventeen-year-old Charlotte Goodall’s sexual advances in a weak moment, while “leading” the ladies through what appears to be paradise (an irony). However, their carping has made the Mexican setting’s loveliness anything but for the withering, white-suited Shannon, who was moved toward dalliances with Carmen Berkeley’s underage nymphet. Whether culturally imposed or self-imposed, prohibition always fails. Ironically, clerical prohibitions (alcoholism, trysts with women), are the spur which lures Shannon to self-destruction.

Already a has-been as a defrocked minister when we meet him, Shannon is hounded by the termagant-in-chief, Miss Judith Fellowes (Lea Delaria), who eventually has him fired. He has no defense for his untoward behavior, nor explanation for his actions, when he diverts the tour, and like a foundering fish gasping for air, flops into the hammock at Maxine’s shabby hotel. There, he discovers that her husband Fred has passed. In her own grieving, desire-driven panic, Rubin-Vega’s Maxine welcomes Shannon as a fine replacement for Fred.

It is an unappealing and frightening offer for Shannon, who views Maxine as a devourer, too sexual a woman, who takes swims in the ocean with her cabana boy servants to cool off the heat of her lusts. Shannon prefers her previous function in her collaboration with Fred, when her protective husband was alive enough to throw Shannon on the wagon, so he could prepare for his next alcoholic fall off of it.

While the appalled Baptist ladies remain offstage, honking the horn on the bus to alert Shannon to leave, and refusing to come up to Maxine’s hotel to refresh themselves, Shannon makes himself comfortable. So do spinster, sketch artist and hustler Hannah (Jean Lichty is less ethereal than the role requires), and her Nonno, the self-proclaimed poet of renown, Jonathan Coffin (Austin Pendleton moves between endearing and sometimes humorous as her 97-year-old grandfather).

Oozing financial desperation from every pore, the genteel pair have been turned away from area hotels. As Hannah gives Maxine their “resume,” the astute owner sniffs out their destitution and is about to show them the door, when the down-and-out Shannon pleads mercy, and Maxine relents. Her kindness earns her chits from Shannon that she will capitalize on in the future. Maxine knows she won’t see a dime from Hannah or her grandfather, whether or not Nonno dramatically discovers the right phrasing and imagery to finish his final poem at her hotel, and earns some money reciting it to pay their bill.

Though the wild and edgy Maxine allows them to stay, she “reads the riot act” to Hannah, suggesting she curtail her designs on the defrocked minister. If Hannah doesn’t go after Shannon, she and her grandfather might stay longer. However, the tension and build up between Maxine and Hannah never fire up to the extent they might have.

To what end does the play develop? Explosions do erupt. Maxine vs. Shannon, and Shannon vs. Miss Judith Fellowes create imbroglios, though they subside like waves on the beach minutes after, as if nothing happened. Only when tour replacement Jake Latta (Keith Randolph Smith), confronts Shannon for the keys to the bus, must Shannon reckon with one who enforces power over him. Neither Maxine, nor her cabana boys, nor Hannah, nor Fellowes can bend Shannon’s will to his knees. Jake Latta’s reality rules the day.

As the bus leaves and his life blows up, Shannon must face himself and end it or begin anew. In the scene between Daly’s Shannon and Lichty’s Hannah after Shannon is tied up in the hammock to keep him from suicide, there is a break through. Daly and Lichty illuminate their characters. Together they create the connection that opens the floodgates of revelation between Shannon and Hannah in the strongest moments of the production. When Nonno finishes his poem and expires, the coda is placed upon the characters who have come to the end of themselves and their self-deceptions. Life goes on, as Shannon has found his place with Maxine who will help him begin again, free as the iguana he set loose. Perhaps.

Williams’ characters are beautifully drawn with pathos, humor, passion and hope. If unrealized theatrically and dramatically, they remain inert, and the audience doesn’t relate or feel the parallels between the universal themes Williams reveals, or the characters’ sub text he presents. Mann’s revival makes a valiant attempt toward that end, but doesn’t quite get there.

For those unfamiliar with the other Iguana revivals or the John Huston film starring Richard Burton and Ava Gardner, this production should be given a look see to become acquainted with this classic. In this revival, there are standouts like Daphne Rubin-Vega as the edgy, sirenesque Maxine, and Pendleton’s Nonno, who manages to be funny when he forgets himself and asks about “the take” that Hannah collected. Lea Delaria is LOL when she is not pushing for humor. So are the German Nazi guests (Michael Leigh Cook, Alena Acker), when they are not looking for laughs or attempting to arouse disgust. That Williams includes such characters hints at the danger of fascist strictures and beliefs, that like the Baptist ladies follow, threaten free thinking beings (iguanas) everywhere.

Humor is everpresent in The Night of the Iguana‘s sub text. However, it is elusive in this revival which siphons out that humanity, sometimes tone deaf to the inherent love with which Williams has drawn these characters. Jean Lichty’s Hannah, periodically one-note, misses the character’s irony in the subtle thrust and parry with Tim Daly’s humorless, angry and complaining Reverend T. Lawrence Shannon. Daly’s panic and shakiness work when he attempts to hide the effects of his alcoholic withdrawal. Both Lichty and Daly are in and out, not quite clearly rendering Williams’ lyricism so that it is palpable, heartfelt and shattering in its build-up to the significance of Shannon’s symbolically freeing himself and the iguana.

The Night of the Iguana with one intermission at The Pershing Square Signature Center on 42nd Street between 9th and 10th until February 25th. https://iguanaplaynyc.com/

‘Orpheus Descending,’ One of Tennessee Williams Most Incisive Works-a Searing Triumph

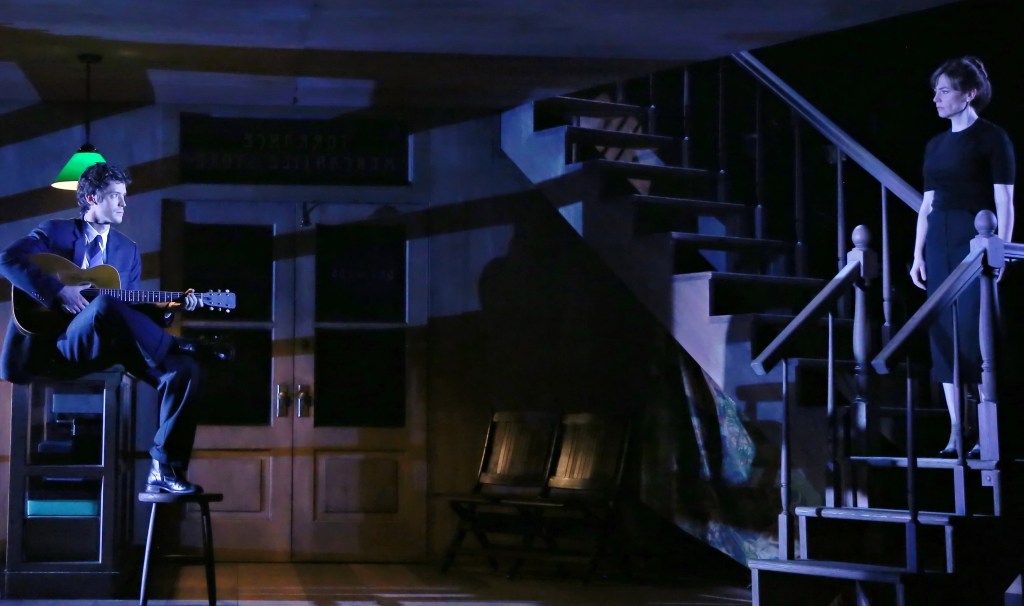

The hell of the South abides in Erica Schmidt’s revival of Orpheus Descending, currently running at Theatre for a New Audience in Brooklyn until August 6th. Tennessee Williams’ poetically brazen work about the underbelly of America that reeks of discrimination, violence, bigotry and cruelty seems particularly regressive in the townspeople of the rural, small, southern, backwater of Two River County, the setting Williams draws for his play.

This production is raw in its ferocity, terrifying in its prescience. It reminds us of the extent to which racists and bigots go feeling self-righteous about their loathsome behaviors when the culture empowers them. The director shepherds the actors to give authentic portrayals that remind us that death lurks in the sadistic wicked who seek to devour those whom they may, especially when their targets have peace and happiness, and step over the line (what the bigots hypocritically think is the line).

At the top of the play, we immediately note that stupidity and hypocrisy exude from the pours of most of the homely white characters. Sheriff Talbot and the wealthy Cutrere family are the chief representatives and purveyors of white supremacist, conservative law and order, which is as natural and welcome as white on rice.

Williams’ brilliant but lesser known work is based on the Orpheus and Eurydice myth. However, Williams updates the allusion and spins it into metaphoric gold transposing the heroic characters into artists, visionaries and fugitives, who rise wildly above the droll deadness of their environs or are delivered from them, as is Lady (Maggie Siff) who is brought to life during her relationship with Val (Pico Alexander). During the course of Val’s and Lady’s dynamic relationship with each other, they seek to cleanse and overcome their past heartbreaks and regrets and move upward toward redemption, reclamation and new beginnings with each other’s help.

The banal atmosphere conveyed by Amy Rubin’s spare, angular, cage-like design of the Torrence dry goods store is an appropriate setting where most of the conflict and interplay among the characters takes place. Its ugly, hackneyed blandness, lack of vibrancy and straight-edged corners symbolize Lady Torrence’s desolate life with the hypocritical, vapid townspeople and her infirm, brutal, racist, hoary-looking husband Jabe Torrance (the irascible, excellent Michael Cullen).

The other two sections of the set, the confectionery (stage left) and the storage area behind the curtain (stage right), Rubin suggests with minimalism. The confectionery and the storage area symbolize the other aspects of Lady’s character that are not governed by Jabe and the destructive, deadening, Southern folkways. The confectionery eventually outfitted with lanterns symbolizes her hope for renewal and reclamation. The intimate, barely lit, storage area where Val sleeps symbolizes the fulfillment of her desire for love.

Center stage is the store and above it the Torrence bedroom, both subscribed by walls which pen Lady in. Along with Jabe, the store’s visitors suck her life-blood dry with the exception of Val and Vee (Anna Reeder), a Cassandra-like character. Above the store, Jabe lies in bed dying. Empty of kind words, Jabe communicates his bile and bitterness by pounding his cane on the floor from his sick bed. It is an ominous foreboding alarm that one imagines the master sends to his slave when he commands something from them immediately.

Into Two River county’s washed-out “neon,” “low-life” mediocrity comes the contrasting light and beauty of the guitar artist/entertainer, the stunning and untouchable Val Xavier. Pico Alexander makes the role his own, portraying Val with grace and alluring, angelic innocence befitting “Boy,” the nickname the assertive, feisty Lady gives him. Siff is sterling and likable as she grows vivacious as their bond develops. Siff’s scene where she reveals she is committed to loving Val, despite not wanting to admit needing him is just smashing.

Val illuminates the spaces he enters and shatters the peace of Dolly Hamma (Molly Kate Babos) and Beulah Binnings (Laura Heisler) when he drops by the Torrence store on Vee Talbott’s suggestion that Lady Torrence might give him a job. As he waits patiently for Jabe and Lady to arrive from the hospital after Jabe’s unsuccessful operation, Jabe’s cousins Dolly and Beulah “eye him” while they prepare a celebration for Jabe’s return.

Vee (the fine Ana Reeder), a spiritual visionary born with second sight, accompanies Val and introduces him to the other women hanging around, one of whom is Carol Cutrere (the superb Julia McDermott), a rebellious hellion whose outsized antics and screaming of the Chocktaw cry with Uncle Pleasant, the conjure man (Dathan B. Williams), make the other women apoplectic. Clearly, Carol is an outsider like Val and Lady, only saved by her last name.

As Vee relates the visions that form the basis of the painting she brings for Jabe to encourage his healing, we note she doesn’t fit in either. If she weren’t married to Sheriff Talbott (Brian Keane) her eccentric ways would banish her from the “polite society” gathered in the store, rounded off by gossip mongers, Sister Temple (Prudence Wright Holmes) and Eva Temple (Kate Skinner), who sneak up the wooden steps to check out Jabe’s bedroom before he and Lady return.

Schmidt stages these opening scenes of William’s claustrophobic setting and characters to maximum effect, clustering the women at the counter and bringing Carol and Uncle Pleasant downstage for their chant and evocation. Downstage is where Carol cavorts, delivers a few soliloquies, and wails her outrage and sorrow as an encomium at the play’s conclusion.

By the time Jabe and Lady arrive and Jabe retires upstairs, we have an understanding of the desolate elements and competing life forces that will drive the conflict forward. Additionally, Williams has the gossips share Lady’s terrible backstory that involves the KKK torching her father’s wine garden, and his gruesome death burning alive in the conflagration because not one firetruck or patron came to his aide.

All this was because he violated the towns’ mores and unwritten law serving wine to “ni$$ers. Implied by Jabe later in the play, the “Wop” had too much life in him and had to be cut down to size and made destitute. Interestingly, Lady’s determined father decided he’d rather burn alive trying to salvage his life’s work than accept poverty and brutality in a death-filled culture. For Lady, the acorn doesn’t fall far from the oak. She decides to take a stand against Jabe and his sadistic brutality than run away with Val.

Alexander’s Val and Siff’s Lady establish their relationship gradually with Siff aggressively taunting Val’s appeal to women, one of whom is McDermott’s live-wire Carol. As their comfort level with each other grows, the two bond over Val’s description of a bird that is so free it never corrupts itself by touching the ground and only does so when it dies. Lady expresses her desire for such freedom, and after their discussion is abruptly interrupted by Jabe’s pounding, we note a greater lightheartedness within Lady. Val’s presence is the freedom and wildness that she craves.

Indeed, we note her mood is uplifted every time Lady has a quiet conversation with Val. The actors have the privilege of organically inhabiting these memorable characters with ease to deliver some of the most figuratively elegant and coherently rich dialogue found in all of Williams’ works. One of their most powerful scenes concerns Val’s description of the corrupt world and his own corruption. He counters it by sharing how his “life’s companion,” his guitar and his music, cleanses his impurity and makes him whole again.

As Val settles in and she begins to rely on him, we realize that her inspiration and actions to reopen the confectionery (Schmidt use of the lanterns descending in the stylized space, stage left) run parallel to Val’s regenerative influence over her. He has ignited her hope and desire to be resurrected from the ashes of the burning, the town’s hatred and racism, and Jabe’s enslavement and ownership of her mental and emotional well being.

In his characterization of Jabe, Williams reveals the psychosis of the Southern Red Neck confederates turned white supremacists that lost the Civil War but persist in acting as if they won it, especially with regard to their racism and hatred of Blacks and “the other,” (immigrants). In Schmidt’s version, we see that Jabe’s attitudes and the attitudes of the other men presciently foreshadow the current MAGA Republicans’ penchant to be brutal and criminally sadistic because their “power” gives them the right, regardless of the truth of the circumstance or the legality. Certainly, Jabe has the power and white supremacist friends (Sheriff Talbot) to back up his actions with impunity.

Thus, as Lady has told Val, she “lives” with Jabe, a figure of death who makes sure to stomp down her happiness or agency every chance he gets. In fact each time Val and Lady seek each other’s company for verbal comfort, Jabe almost intuits that she is uplifted away from his presence and claws and pounds (with his cane) his way back into her mind and emotions with his demands. She always goes running to him, for in her soul, she feels she has no other options.

The turning point arrives when Jabe comes downstairs to exert himself over the cancer that is killing him and perpetrate some new malignity against her, which appears to be the only pleasure he has. His emotions are pinged to remembrance when he views the loveliness of the confectionery and the new life that has inspired it (Val). It is then he strikes at Lady provoking her past reason, a white supremacist sadist to the last.

There are no spoilers. What transpires is Williams’ reaffirmation of the modern day tragedy that resulted daily in the Jim Crow South when white supremacists asserted they won the Civil War with every Black person they lynched using law enforcement to cover for them. In the play Williams also infers how this happens in the inhuman, abusive prison system which prompts men to escape and uses the escape as the justification for their killing.

Schmidt and her team have created a production that is bold in revealing Williams’ trenchant themes about death, life, hatred, bigotry, racism and the utter wicked sadism and evil that would keep such a culture going even if the culprits, like Jabe, suffer and are eaten alive by their own hatred. In revealing Williams’ prescient themes that apply for us today, we note that a racist culture cannot be confronted when the power is held by the racists and bigots. Indeed, one must escape the purveyors of death and leave their sphere of influence, if there is no federal oversight or punishment for law breaking. If there isn’t accountability, the individuals, will do as they please, and like despots bend their underlings to their will as death dealers.

Kudos to the creative team which includes Jennifer Moeller’s costume design, David Weiner’s lighting design, Cookie Jordan’s hair and wig design and Justin Ellington’s original music and sound design.

The production concludes August 6th. Don’t miss it for its profound characterizations beautifully acted, acute ideas Schmidt suggests with her fine direction and the technical production values that bring Williams’ stark truths to bear on us today. For tickets and times go to their website https://www.tfana.org/visit/ticket-venue-policies

‘TRUMAN & TENNESSEE: An Intimate Conversation’ Telluride Film Festival, Hamptons International Film Festival, Seattle International Film Festival Review

Truman Capote and Tennessee William were friends over the forty year period they wrote, teased/ridiculed each other, basked in each other’s humor and love and grew envious, only to meet for dinner one last time before Williams died of a barbiturate overdose and Capote followed him, dying of alcohol complications 18 months later. Tennessee, the 13-year elder, met Truman when he was 16-years-old. He was charmed and delighted by his wit and personality and Truman believed Tennessee to be a genius. From then on they became fast intellectual friends whose relationship provides a fountain of lyricism, wisdom and exquisite writing for the curious.

This beautifully rendered poetic account of these two giants of American literature by Lisa Immordino Vreeland is a haunting, must-see, cinematic in memoriam. What makes her film doubly enjoyable is the superb and spot-on voice-over narration by Zachary Quinto (as Tennessee Williams) and Jim Parsons (as Truman Capote). Without their appreciation of these individuals, the realism that they brought to Capote’s and William’s voices and intentions would not have been as acute.

Vreeland selects choice quotes from the writers’ letters, telegrams, articles, TV interviews (David Frost and Dick C avett) and illustrative snippets from the original films of their work (A Streetcar Named Desire-1951, Baby Doll-1956, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof-1958, Suddenly Last Summer-1959, The Fugitive Kind-1960, Sweet Bird of Youth-1962, The Night of the Iguana-1964, The Glass Menagerie-1987, Breakfast at Tiffany’s-1961, In Cold Blood-1967, The Grass Harp-1995). The last three films in the list are from Capote’s works.

The filmmaker astutely supplements these clips with many archived photos (a rare one of Laurette Taylor in the original production of The Glass Menagerie). These also include historical, personal photos from Capote’s and Williams’ youth through the aging process. Thus, we see photos of their parents, relatives, studio portraits, friends and imagistic reflective moments. Also presented are their visits to Ischia and video clips of Rome and elsewhere with intriguing voice-overs by Quinto and Parsons.

Vreeland wisely moves in chronological order starting with their beginning successes, after she introduces both individuals in their separate David Frost interviews. David Frost and Dick Cavett remind us of their insightful, sensitive attention as listeners. Their winsome charm elicits the trust of their interviewees who allow them to go to places which at times are uncomfortable. Just seeing these clips as a remembrance of how in-depth interviews were conducted is a historical record. It was something the seeing public was used to (not duplicated anywhere on mainstream TV today).

Success for Williams began in 1945 with A Glass Menagerie (one of the most performed plays on the planet). With Capote his first novel Other Voices, Other Rooms was published to acclaim in 1948. Vreeland carefully organizes her subjects with refreshing candor. She often backtracks according to Capote’s and Williams’ responses to the searching questions by David Frost and Dick Cavett. The hosts ask them about friendship, love, self-identification, sexuality, parents, upbringing and more. Then Vreeland extrapolates and illustrates with voice-over quotes and snippets of their work. She ties all together with narrative and bridge photography of scenery or stills that relate to their lives (where they lived, traveled, partied).

As a result of this varied structure, she remains flexible in her use of archived photos, videos and films and Williams and Capote’s thoughtful comments that Parsons and Quinto narrate. This is a kaleidoscope that elucidates brilliantly; it is a fascinating intimate capture of both men as writers, celebrities and individuals.

Heightening the exceptional and seamless account are the voice-over quotes spoken by Parsons (Capote) Quinto (Williams). Their inflections, accents, the expressed emotion, pacing and silences immeasurably resonate to meld with the carry-over shots. The visuals and the audio with smooth synchronicity are stunning because of the matched cinematography; it’s like words and music that cohere and inform one another.

The film is a tone poem. What Vreeland and her creative team deliver is breathtaking. Importantly, because it is so well crafted, the personal information we learn becomes a delightful exercise in the study of who these mysterious writers were and still are, for their impact on our culture and global culture continues. Certainly, these artists have achieved a timeless immutability in their work. Vreeland’s respect for these artists helps us appreciate them and their relationship all the more. Whatever the weather between them, it is clear that they influenced and impacted each other’s work.

Foremost, Williams and Capote considered themselves artists, then writers and celebrities. Brutally honest in the interviews with Frost, they also reveal their playful mischievous natures. They express their reactions to their homosexuality growing up and afterward when they had to reside in worlds of pretense which sheltered them. Both were rejected by parents. Williams mentions that he and his father didn’t get along; his father didn’t like him very much the more he stayed home and got to know him. Capote’s mother remarried. She took him to a doctor because of his homosexuality and asked that he be given shots. Capote interpreted this to mean she thought him a monster.

Their honesty about whether they “like” themselves, if they think friendship is more important than love, whether they had affairs and a discussion of their thoughts as writers and how writing is paramount to who they are remain telling. Both battled depression with drugs and alcohol. Dr. Feel Good was their man for escape as it was for many celebrities at that time. Their responses to Frost’s questions, “Are you happy?” are both wise and intensely human. Williams’ discussion about the subjects in his plays (lobotomy, mental illness, cannibalism, rape) are philosophical and realistic.

Capote discusses how his work and effort on In Cold Blood took so much out of him, he was never the same again. He did witness Perry’s death which must have given him PTSD. The research and interviews of the murderers so impacted him, he asked his great friend Nell (Harper Lee) to join him to keep him company as well as have her help him solicit interviews with the otherwise aloof townspeople. He says that in a way, he died working on In Cold Blood; the metaphoric comment is just the tip of the iceberg in what Capote wanted to achieve and achieved in creating a new genre: narrative non-fiction.

Truman ad William admitted that, like all authors, their work has elements of auto-biography and is personal. Additionally, they affirmed their compulsion to write and create worlds of their own inhabited by characters they liked to spend time with. Williams pointed out the loneliness of writing. Though acknowledging it, Capote didn’t mind that as much.. Vreeland makes clear that their writing and the characters in their works occupied them with surprising turns of behavior. Capote likened writing to artistry that can reach a form of grace. Without mentioning the G-o-d word, he implied that there is a divinity or extraordinary place that great writing touches making it human and identifiable.

This certainly is a must-see film for anyone who is a writer or anyone who aspires to be a writer. They will be affirmed and encouraged by what these two icons share.

From editing to cinematography, from direction of Parsons and Quinto and the selection of all the quotes, video clips and archived material, all kudos to Vreeland. Her amazing work should be shown to literature and drama classes in colleges and high schools who investigate and read Williams and Capote. The film flies by, never snagging in dead spots, a feat in itself.

TRUMAN & TENNESSEE: An Intimate Conversation opens JUNE 18 in New York at Film Forum. It opens in Los Angeles at The Nuart and Laemmle Playhouse & Town Center 5. The film also is available in virtual cinemas nationwide through KinoMarquee.com

‘The Rose Tattoo,’ Marisa Tomei Is Tennessee Williams’ Fiery, Sensual Serafina, in a Stellar Performance

Marisa Tomei in ‘The Rose Tattoo,’ by Tennessee Williams, presented by Roundabout Theatre Company (Joan Marcus)

Atmosphere, heat, the heavy scent of roses, candles, mysticism, undulating waves, torpid rhythms, steamy melodies, fantastical rows of pink flamingos, a resonant altar of the Catholic Madonna. These elements combine to form the symbolic backdrop and evocative wistful earthiness that characterize Roundabout Theatre Company’s The Rose Tattoo at American Airlines Theatre.

Tennessee Williams playful, emotionally effusive tragic-comic love story written as a nod to Williams own Sicilian lover Frank Merlo, is in its third revival on Broadway in a limited engagement until 8th December (the Catholic date of the Feast of the Immaculate Conception). Reflecting upon Marisa Tomei’s portrayal of Serafina in The Rose Tattoo, this is an ironic, humorous conclusion in keeping with the evolution of her character which Tomei embraces as she exudes verve, sensuality, fury, heartbreak and breathtaking, joyful authenticity in the part.

If any role was made for Tomei, divinity and Tennessee Williams have placed it in her lap and she has run with it broadening the character Serafina Delle Rosa with astute sensitivity and intuition. Tomei pulls out all the stops growing her character’s nuanced insight. She slips into Serafina’s sensual skin and leaps into her expanding emotional range as she morphs in the first act from grandiose and joyful boastfulness to gut-wrenching impassioned sorrow and in the second act to ferocity, an explosion of suppressed sexual desire and its release. All of these hot points she elucidates with a fluidity of movement, hands, limbs, head tosses, eye rolls which express Serafina’s wanton luxury of indulgent feeling and effervescent life.

The contradictions of Serafina’s character move toward a hyperbolic excess of extremes. When speaking of her husband Rosario and their relationship, their bed is a sanctum of religion where they express their torpid love each night. She effuses to Assunta (the excellent Carolyn Mignini) how she mysteriously felt the conception of her second child the moment it happened. A rose tattoo like the one her husband Rosario wore on his chest appeared like religious stigmata without the dripping blood. And it burned over her heart, a heavenly sign, like others she receives as she talks to the statue of the Madonna, and remains a worshipful adherent to Mother Mary, praying and receiving the anointed wisdom whenever necessary.

Marisa Tomei, Emun Elliott in ‘The Rose Tattoo,’ by Tennessee Williams, presented by Roundabout Theatre Company (Joan Marcus)

Rosario’s family is that of a “baron,” though Sicily is the “low” country of Italy and an area fogged over with undesirables, thieves and questionable heritages as the crossroads of Europe. We know this “baron-baroness” is an uppity exaggeration from the looks on the faces of her gossipy neighbors and particularly La Strega (translated as witch) who is scrawny, crone-like and insulting. Constance Shulman is convincing as the conveyor of Ill Malocchio-the evil eye. Her presence manifests the bad-luck wind that Assunta refers to at the top of the play and to which Serafina superstitiously attributes the wicked event that upends her life forever.

Williams’s characterization of Serafina is brilliant and complex. Director Trip Cullman and Tomei have effected her intriguing possibilities and deep yearnings beyond the stereotypical Italian barefoot and pregnant woman of virginal morals like Our Lady. It is obvious that Tomei has considered the contradictions, the restraints of Serafina’s culture and her neighbors as well as her potential to be a maverick who will break through the chains and bondages of her religion and old world folkways after her eyes are opened.

We are proud that Serafina disdains the gossiping neighbors with the exception of Assunta and perhaps her priest. Though Serafina’s world does not extend beyond her home, the environs of the beach, her daughter Rosa (Ella Rubin) and Rosario, a truck driver who transports illegal drugs under his produce, she is a fine seamstress. And in her business interactions with her neighbors and acquaintances, we note that she has money, is industrious, resourceful and a canny negotiator.

It makes sense that Rosario (whom we never see because he is a fantasy-Williams point out) treats her like a baroness filling their home with roses at various times to reassure her of her grandness. And the poetic symbol of the rose as a sign of their love and the romance of their relationship is an endearing touch, reminiscent of the rose tattoo on his chest signifying his commitment to her. At the outset of the play, a rose is in Serafina’s hair which she wears waiting for Rosario to come home. As she does, we believe she is fulfilled in their love and the happy status of their lives in a home on the shores of paradise, the Gulf Coast of Mississippi.

What is not manifest and what lurks beneath becomes the revelation that all is not well, that her Rosario is not real, but is an illusion. Typical of Williams’ work are the undercurrents, the sub rosa meanings. The rose is also a symbol of martyrdom, Christ’s martyrdom. And it is this martyrdom that Serafina must endure when word comes back that Rosario has been killed, burned in a fiery crash which warrants his body be cremated. Unfortunately, the miraculous son of the burning rose on her chest that appeared and disappeared, she aborted caused by the extreme trauma of Rosario’s death.

Marisa Tomei, Emun Elliott in ‘The Rose Tattoo,’ by Tennessee Williams, presented by Roundabout Theatre Company (Joan Marcus)

The rose as Williams’ choice symbol is superbly complex. For Rosario’s rose tattoo also represents his amorous lust for women, one of whom is Estelle Hohengarten (Tina Benko) who asks Serafina to make a gorgeous, rose-colored silk shirt for “her man.” When Estelle steals Rosario’s picture behind Serafina’s back, we know that Rosario led a double life and we are annoyed at Estelle’s arrogance and presumption to ask his wife to make such a gift shirt. But in William’s depth of characterization for Estelle, most probably Rosario is also philandering on Estelle who, to try to keep him close, gives him expensive gifts like hand-made silk shirts.

Williams clues us in that her faith and passion for Rosario has blinded her judgment and overcome her sharp intellect and wisdom. In fact it is an idolatry. Her religion stipulates that no human being should be worshiped or sacrificed for. Serafina’s excessive personality has doomed her to tragedy, betrayal and duplicity with Rosario. Ironically, his death is her freedom, but she must suffer his and her son’s loss ,a burden almost too great to bear, even for one as strong as Serafina who does become distracted, unkempt and uninterested in life.

Because Rosario, the wild rose with thorns is not worthy of Serafina’s love, after his death there is only pity for the cuckholded Serafina and a finality to her exuberant life until the truth of who Rosario really was lifts her into a healthy reality. Tomei’s breakdown is striking and Williams creates the tension that in weeping for the “love” of her life who indeed has betrayed her, she will be wasting herself. He also affirms the huge gulf between her ability to live again and her lugubrious state which continues for three years as she mourns an illusion.

The question remains. Will she come to the end of herself? The romantic fantasy held together with the glue of her faith and the enforced, manic chastity of her old world Italian mores must be vanquished. But how? It is in the form of the charismatic and humorous Alvaro Mangiacavallo. But until then Serafina withers. Isolating herself, she implodes with regret, doubt, sorrow and dolorous grief, as well as anger at her daughter Rosa who wants to live and find her own love like her mother’s.

The mother-daughter tensions are realistically expressed as are the scenes between Tomei and Jack (Burke Swanson) Rosa’s boyfriend, which are humorous. Altogether, the second act is brighter; it is companionable comedy to the tragedy of the first act.

When she meets Alvaro, in spite of herself, she responds with her whole being to his attractiveness. As they become acquainted, she accepts his interest in her for what she may represent; a new beginning in his life. It is a new beginning that he tries to thread into her life to resurrect her sexual passions and emotions of love. Thus, he pulls out all the stops for this opportunity to win her, even having a rose tattooed upon his chest in the hope of taking Rosario’s place in her heart.

Marisa Tomei, Emun Elliott in ‘The Rose Tattoo,’ by Tennessee Williams, presented by Roundabout Theatre Company (Joan Marcus)

Emun Elliott is spectacular as the clownish, emotionally appealing, lovable suitor who sees Serafina’s worth and beauty and attempts to endear himself to her with the tattoo. Along with Serafina’s discovering Rosario’s betrayal, Elliott’s portrayal of Alvaro solidifies and justifies why Serafina jumps at the opportunity to be with him. He is cute. He is real. He is as emotional and simpatico as she is. He is Sicilian and above all, he is available and interested in her. It is not only his steamy body that reminds her of Rosario’s, but she is attracted to his humor, sensibility and sensitivity of feeling which mirrors hers.

After discovering Rosario’s duplicity, understanding Alvaro’s concern and care for three women dependents and his honesty in admitting he is a buffoon disarms Serafina. Alvaro’s strength and lack of ego in commenting that his father was considered the village idiot is an important revelation for her as well. Indeed, as she views who he is, she senses that his humility and humorous self-effacement is worth more than all of Rosario’s boastfulness that he was a baron which he wasn’t.

As the truth enlightens her, Tomei’s Serafina evolves and sheds the displacement and her sense of confusion and loss which was also a loss of her own imagined “secure” identity as Rosario’s “wife.” Wife, indeed! Rosario’s mendacity made her into a cuckhold and a brokenhearted fool over a man who was not real. At least Alvaro is real. The comparison between the men reinforced with Rosario’s unfaithfulness, which she can now admit to herself, prompts her to reject the religion that kept her blinded and the antiquated mores that made her a fool and kept her alone and in darkness.

Shepherded by Cullman, Elliott and Tomei create an uproarious, lively and fun interplay between these two characters who belong together, like “two peas in a pod” and have only to realize it, which, of course, Alvaro does before Serafina. Tomei’s and Elliott’s scenes together soar, strike sparks of passion and move with the speed of light. The comedy arises from spot-on authenticity. The symbolic poetry, the shattering of the urn, the ashes disappearing, the light rising on the ocean waves (I loved this background projection) shine a new day. All represent elements of hope and joy and a realistic sense of believing, grounded in truth for both protagonists.

Tomei, Elliott, Cullman and the ensemble have resurrected Williams’ The Rose Tattoo keeping the themes current and the timeless elements real. Duplicity, lies, unfaithfulness, love and the freedom to unshackle oneself from destructive folkways that lead one into darkness and away from light and love are paramount themes in this production. And they especially resonate for our time.

I can’t recommend this production enough for its memorable, indelible performances especially by Elliott and Tomei shepherded with sensitivity by Cullman. The evocativeness and beauty of the staging, design elements and music add to the thematic understanding of Williams’ work and characters. Kudos goes to the creative team: Mark Wendland (set design) Clint Ramos (costume design) Ben Stanton (lighting design) Lucy Mackinnon (projection design) Tom Watson (hair and wig design) Joe Dulude II (make-up design). Bravo to Fiz Patton for the lovely original music & sound design.

The Rose Tattoo runs with one intermission at American Airlines Theatre (42nd between 7th and 8th) until 8th December. Don’t miss it. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

Theater Review (NYC): ‘A Lovely Sunday For Creve Coeur,’ by Tennessee Williams, Starring Kristine Nielsen, Annette O’Toole, Jean Lichty

(L to R): Jean Lichty, Annette O’Toole, Kristine Nielsen, Polly McKie in ‘A Lovely Sunday For Creve Coeur,’ directed by Austin Pendleton (Joan Marcus)

Tennessee Williams dramatized women’s quiet lives of desperation. Indeed, his characterizations ping from the haunting, tragic-comedic melodies of emotion he experienced with his family growing up in St. Louis, Missouri. In A Lovely Sunday For Creve Coeur, directed with measured grace by Austin Pendleton, one of Williams’ last plays receives a sterling, masterful presentation. Assuredly, the excellent ensemble of actors provides the poignant atmospheric intensity.

Currently running at Theatre at St. Clement’s, the production deserves a visit for its adroit performances and direction. Pendleton’s nuanced and gradual unfolding of Williams’ dramatic climax at once captivates with its beauty, delicacy, and plaintiveness. Delivered with a less astute balance in shepherding the actors’ portrayals than Pendleton’s, Williams’ complicated play would not deliver the power and heart-break that this production evokes at the conclusion.

(L to R): Kristine Nielsen, Jean Lichty, ‘A Lovely Sunday For Creve Couer,’ Tennessee Williams, directed by Austin Pendleton (Joan Marcus)

Throughout the play we witness three single women’s wants and desires. A fourth, who becomes a foil for the other three, provides the background theme which motivates them to desperation. Each longs for happiness away from her current day to day lower class existence in depression era St. Louis, Missouri. In order to achieve this happiness, they place their hopes in others to deliver it. Ultimately, the women deceive themselves. Clearly, they set themselves up for disappointment after disappointment.

At the opening we note that maternal, nurturing Bodey (Kristine Nielsen in a superb, layered, and profound rendering), chides Dorothea. With precision Jean Lichty portrays the teacher, a fading Southern belle from Tennessee. Lichty’s somewhat frivolous Dorothea spends her entire morning waiting upon Mr. Ralph Ellis’s phone call. Because Bodey is “deaf” and didn’t hear the phone ring when it did, we become persuaded by Dorothea’s view. Initially we believe her relationship with Ralph remains solidly founded. Meanwhile, Bodey prepares food for a lovely outing at Creve Coeur with her twin brother Buddy, anticipating that Dorothea will join them. She insists she will not, for Ralph Ellis has important information to tell her about their lives together.

Strikingly, we see that neither women really listens to the other as each drives forward to achieve their own goals. Dorothea yearns for Ralph, a principal who associates with the country club set. Because of her recent tryst with him, she anticipates that her charms have overwhelmed him romantically as she has been overwhelmed. The inevitability remains clear for her, though Bodey warns her against these notions.

Bodey’s reaction to Dotty’s relationship with Ellis appears questionable. We wonder at Bodey’s potential jealousy of “their love.” The feminine, sweet, pretty Dorothea surely will leave her and get married, a frightening prospect for Bodey. Indeed, Dotty believes that eventually, Ralph will spirit her into a well positioned marriage away from the squalid, spare lifestyle she leads teaching, and renting from Bodey. For her part Bodey, a spinster devoted to caring for others, least of all herself, has given up on her own prospects of marriage. Instead, she believes that her overweight, reliable, unromantic, hearty twin Buddy would be perfect for Dorothea. And if they married, she would be the dependable aunt who would raise their brood and have a vital purpose in their family life.

(L to R): Jean Lichty, Annette O’Toole, Kristine Nielsen in ‘A Lovely Sunday For Creve Coeur,’ directed by Austin Pendleton (Joan Marcus)

During the course of the play, two other spinsters join into this group of women who appear unloved and unwanted. Miss Gluck, a German neighbor who has lost her mother and who grieves incessantly. Most probably not only does she grieve the close relationship loss. But she probably grieves that she will be alone. Thus, she must give herself her own solace daily. Indeed, how much can Miss Gluck rely on the friendship of her neighbor Bodey with whom she communicates only in German? Polly McKie as the mournful Miss Gluck is humorous and believable. Thematically, the character portends what happens to women who do not marry well economically or congenially, or whose husbands abandon them to loneliness and despair.

Annette O’Toole and Polly McKie in ‘A Lovely Sunday For Creve Coeur,’ directed by Austin Pendleton, written by Tennessee Williams, La Femme Theatre Productions (Joan Marcus)

Helena is the fourth spinster who intrudes into the lives of Bodey and Dotty. During the course of her visit, she suggests the monstrous end which awaits the unfortunate Miss Gluck. Incisively portrayed by Annette O’Toole, Helena represents the cruel and bitter archetype of the most miserable of the spinsters. These yearn to escape themselves and falling short, grow venomous and predatory toward other women. Arrogant, acerbic, biting she manipulates with sarcasm. And she bullies and demeans Bodey and Dotty with female cultural mores and the pretense of good breeding. In irony she implies that unless Dotty takes actions to lift herself into an upscale arrangement with her, she will fall into the same despair as Bodey. And with finality, poor Dotty will eventually become a social anathema, the greying, unwanted, depressive Miss Gluck.

As the day unfolds, we learn Helena, too, has wants. A fellow teacher in the same school, she intends for Dotty to be her roommate and share the expensive rent and utilities. Her concern for Dotty’s life path concludes with self-dealing. Her own. She covets the monthly expenses Dotty will hand to her. And she intends Dotty to partner up at their bridge games twice a week for companionship. When Dotty inquires whether the bridge will be mixed, we see the fullness of Dotty’s fear anguish of discouragement.

For Dotty, there is no hope without a man. She cannot define herself in any other terms. Nor can she settle for a kind of contentment or resignation as Bodey, Helena and even Miss Gluck have. For her it’s a man, or it’s the abyss. That her designs fall upon Ralph Ellis and certainly not the overweight, unappealing Buddy, who accompanies his sister to Creve Coeur, is her tragic misfortune.

Tennessee Williams’ ironies and humor seek a fine level in this satisfying and heartfelt production. Notably, the Rolling Stones anthem to humanity rings out loudly in this play’s themes of disappointment and finding one’s courage to move past despair. No, “You Can’t Always Get What You Want!” However, for some of the characters, especially the ones who nurture and look out for each other, they do “get what they need.” Perhaps. Indeed, they may even enjoy a lovely Sunday at Creve Coeur.

Kudos to the artistic team Harry Feiner (Scenic & Lighting Design), Beth Goldenberg (Costumes), Ryan Rumery (Sound Design & Original Music), and the other artists.

A Lovely Sunday For Creve Coeur presented by La Femme Theatre Productions runs without an intermission at Theatre at St. Clement’s (423 West 46th St) until 21 October. Interestingly, the theater was founded by Tennessee William’s cousin Reverend Sidney Lanier. You may purchase tickets at LaFemmeTheatreProductions.org.