‘Here There Are Blueberries,’ No Evil. Just Ordinary, Enjoyable Routines.

Here There Are Blueberries, now in its third extension at New York Theatre Workshop, is a many-layered, superb production running until June 30. Stylized and theatricalized as a quasi-documentary that travels back and forth from present to past to present by enlivening characters in various settings, the play unravels the mysteries centered around an album of 116 photographs taken at Auschwitz. Though the album has no photographs of the victims to be memorialized, it eventually is donated to archivists at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, by a retired U.S. Lieutenant Colonel.

Based on real events, interviews, extensive research and photographs rarely seen of the infamous concentration camp from another perspective, the play follows archivists who shepherded the photographic artifacts toward a greater understanding of the political attitudes and the daily routines of the people who ran the camp. Written by Moises Kaufman and Amanda Gronich, and directed by Moises Kaufman, Here There Are Blueberries is a salient, profound work that has great currency for our time.

With expert projection design by David Bengali, Derek McLane’s scenic design, which suggests the archivists’ workplace, and Kaufman’s minimalism, characters/historical individuals step forward to bear witness, like a Greek chorus, to speak from the ethereal realms of history. The play which has some Foley sound effects for purposes of interest, dramatizes scenes which hover around a concept. All of the fine artistic techniques by Dede Ayite (costume design), David Lander (lighting design), Bobby McElver (sound design), further the plays probing themes which examine questions the researchers ask about those who murdered and why they murdered. As the drama poses questions to its audience and itself, some, the play answers. Others, the audience must answer for themselves.

At the outset, a narrator explains the importance of the Leica camera for the people of Germany in the 1930s, when the society was at a crossroads after economic depression and the reformation of Hitler’s new government. Perched on a stand center stage is the camera in the spotlight, while projections of black and white photos scroll in the background, exemplifying the subjects taken by people using it. Some are of German people enjoying family events, as we note the narrator’s comment that in Germany, amateur photographers took up the activity as a national pastime and became “history’s most willing recorders.”

As the photos scroll showing stills of children and young adults giving the Hitler salute, the narrator suggests that “each frozen moment tells the world this is our shared history.” Her tone is ironic and the Hitler salute, as terrible as it is, physicalized by the bodies of children, indicates an alignment with Hitler’s politics, attitudes and way of life. Additional photos of children and adults enjoying outings, show Nazi flags; the narrator continues, the “apparent ordinariness of these images does not detract from their political relevance.” Indeed, she states, “On the contrary: asserting ordinariness in the face of the extraordinary is in itself, an immensely political act.”

In photographs and videos of Hitler’s marches by soldiers of the Third Reich (shown in the Nazi propagandist films of Leni Riefenstahl, etc.), we note Nazi militarization and might, which after a while are easily relegated to “the past.” Photographs throughout the play’s album note the Nazi flag, Hitler salute and SS uniform as a common fact of life lived at that time. Indeed, Hitler’s politics became the breath of life itself and all aspects of the German people’s existence and happiness were intertwined with Nazism, Hitler’s “great” leadership, his conquests, economic prosperity, and the ready identification with all of this by the average German. This was so until things went terribly sour and German war losses multiplied.

However, the Third Reich’s asserting ordinariness and commonality, when in fact it was anything but, is one of the concepts the archivists deal with throughout their journey to organize the photographs, categorize them and analyze what they are looking at in the photo album of the SS’ lives at Auschwitz.

The playwrights introduce us to the archivists in the second scene. It is then Rebecca Erbelding (Elizabeth Stahlmann), first reads the letter from the Lieutenant Colonel notifying the museum that an album with photographs from Auschwitz that he possesses might be of import. From that juncture on, we become engrossed in the archival journey as the researchers, experts and others delve into the album and attempt to understand it. Curiously, there are no photos of the victims and prisoners of Auschwitz.

As they take on the difficult task and uncover details through trial and error, eventually, researchers bring together the puzzle pieces which explain the photographs and identify the SS officials and the various workers up through the hierarchy, who helped Auschwitz seamlessly function. Clearly, Auschwitz was a huge endeavor that contained an industrial complex and barracks for laborers, housing for guards and administrators alike, and a killing machine and ersatz assembly line of death.

After pinpointing the owner of the album as Karl Höcker, who moved his way up to become the administrative assistant to the head of Auschwitz., the archivists (who also bring to life Karl Höcker and others via dramatization), gradually explore the lifestyle of those in the photographs. These include the SS guards, top brass, doctors, various secretaries (Helferinnen, who were in communications, etc., and held jobs at the camp), staff and others having meals, relaxing at a nearby resort and more daily activities.

None of the photos show the functions of Auschwitz, the prisoners, victims or crematoria. All is pleasant and reflective of the wonderful world that Hitler spoke about bringing to mankind after the “vermin” were removed. That the Helferinnen were photographed surprised a number of researchers who wondered if the young women knew about the gas chambers in the camp or smelled the acrid air of burning flesh in the crematoriums. After denials and relatives probing and finding innocence, what the women knew is later answered by one of the secretaries who was at Auschwitz. She was questioned after the war. Charlotte Schunzel stated she and the other women recorded how many were sent to hard labor and how many were sent to SB, “special treatment,” a euphemism for the gas chambers.

The archivists pin down the identity of the SS officers and high command in the photographs, one of whom was the notorious “Angel of Death,” Dr. Menegele. Another is the commandant who set up Auschwitz-Birkenau, Rudolph Höss. The researchers determine that the photos are like selfies that reveal the happy life of Karl Höcker (Scott Barrow), who would have been a “nobody” if he had not joined the Nazi party in 1937 and arrived at the camp in 1944, just in time to help “process” the thousands of Jewish Hungarians (350,000), who rode in trains three days, only to be murdered in gas chambers after they arrived.

Kaufman and Gronich seize our interest especially when actors take on historical personages, relatives of the SS, survivors, researchers, historians and others. in view of the audience, actors create Foley sound effects to usher in events and accompany Erbelding, Judy Cohen (Kathleen Chalfant), Charlotte Schunzel (Nemuna Ceesay), Tilman Taube (Jonathan Ravlv), Melita Maschmann (Erika Rose), Rainer Höss (Charlie Thurston), Peter Wirths (Grant James Varjas), and others as they uncover bits of information and puzzle together what is happening in each photograph.

The global attention the album receives (revealed by projections of headlines), brings new interest and revelations, some by grandchildren of the SS who are horrified to see uncovered aspects of their relatives they didn’t want to imagine. These aspects have been kept hidden from families out of shame and especially to avoid accountability. Perpetrators of murder and the accomplices to murder are still being located and held to account, even as recently as the last two years. Murderers and the complicit and culpable had a great need for covering up their crimes, as long as they were alive.

Another revelation comes from Holocaust survivor Lili Jacobs, who contacts archivists, as a result of the press reports. She had been holding on to an album she uncannily found of 193 photographs of the Hungarians arriving on the trains, all of whom were “processed” by the SS and high command in the photos. After she donates her album (it contains pictures of herself and family taken by the SS in the camp the day she arrived from Hungary), the researchers are able to solve the dates of the mystery of one photo which shows all the SS, high command and workers celebrating at Solahütte (a resort), where Karl Höcker occasionally rewarded the SS guards, workers, Helferinnen etc., when they did something special.

One example is given when guards prevented an escape by killing four prisoners. Administrator Höcker rewarded them for their “courage” by sending them to Solahütte for a few days.

Previously, the archivists couldn’t understand what and why the large group of camp officials, workers, drivers, Auschwitz staff, referred to by one archivist as the “Chorus of Criminals,” were photographed celebrating. However, through interviews with experts, and piecing together the facts, they divine why the entire group of Auschwitz Nazis standing and smiling, were enjoying the accordion music in one, fine, inclusive photograph, from the top brass in the front, to the lowly staff standing on a hill in the back.

With the evidence of the two albums together, archivists complete the full story of murderers and victims. The victims in Jacobs’ album were those who arrived in train transports from Hungary. The photographs included photographs of Lili and her family and her rabbi, right before they were separated into the lines for labor camp and gas chambers. In Höcker’s album, the administrator assembled and photographed the “Chorus of Criminals'” photograph for a vital reason. The murderers celebrating at Solahütte were congratulating themselves. They had successfully finished a job well done, the massive operation, processing Hungarians, dividing and selecting, so that 350,000 could be exterminated, among them Lili’s parents and two younger brothers.

Through their research, archivists discovered that Lili arrived one day after Höcker arrived at Auschwitz. He most probably received a career bump up to administer the massive “Hungarian Project.” In light of Lili’s discovery and sharing it with the archivists at the museum, she and they “get the full picture.” She sees the identity of the men who murdered her family. Finding the album of herself in the tie in with the album of the SS who ran the camp is an extraordinary sequence of events that is beyond coincidence. For her, the discovery is mystical and divinely spiritual.

Ironically, in Here There Are Blueberries, the victims that the Holocaust Memorial Museum has been so diligent about uplifting and respecting are not the only ones to be considered in studying and understanding the Holocaust. The innocent victims, indeed, were the extraordinary ones in Hitler’s politics that had infiltrated into the bones of the German people, but not the bones of the innocent ones ravaged by acts of the brutal tragedy delivered for the “good of the nation” in its lust for domination. The victims’ impossibly painful stories of survival or loss, escape, surrender, the trauma, and the horror, shock, astound and enrage.

That the ones who perpetrated murder and genocide were able to do it day in and day out as a matter of routine, a job to be done, exemplifies the normalization and internalization of a monstrous political attitude. That attitude that the SS, many Germans and surrounding cultures (i.e. Austria) adopted as right and true, a way of being, a way to live one’s life, which necessitated that others bleed and die for it as a general social good, is evidenced throughout Hocker’s album of photographs of the SS’s smiling faces as they perform daily activities.

It is this above all that Kaufman and Gronich bring to the table and highlight like no other work, with the exception of Martin Amis’ novel Zone of Interest, about the life of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss, which was recently made into a film, directed by Jonathan Glazer. However, unlike Zone of Interest, Kaufman and Gronich don’t include responsive photos to the crematoria. All photos of camp function and purpose are missing. Only in Lili Jacobs’ companion album do we note the horror of the transports and the photos of her rabbi, her parents and siblings who died.

The photos of those accountable for all of the activities at Auschwitz, their reason for being there-to kill, oppress, subjugate and promote the war effort-is implicit. Their very images in the photographs stink with the noisome odor of the gas chambers. The absence of the victims and any evidence of the killing machine, a final realization of the archivists who investigate the album, if anything, incriminates all of the SS officers even more in their guilt. If they were innocent and in the right, why did Höcker need to edit out the buildings of the killing machine, the prisoners and torturing that happened in the labor complex? Why did he need to present his album of “happy days are here again?” when obviously the smoke of the burning had to be hidden?

In the archivists’ explorations they learned the backgrounds of the SS running the camp were ordinary-former clerks, bank tellers, confectioners, teenage girls. We are prompted to ask what separates these murderers and accomplices to murder from the rest of us? Stating the Nazis were monsters allows us the luxury to say “we are not like them.” It dupes us to think we would never be caught up as these were, convinced in the rightness of their actions. This is a dangerous attitude. Indeed, playwright Kaufman reflects the overriding theme of Here There Are Blueberries when he states that “the Nazis were not monsters-they were normal people who did monstrous things.”

How are political cults convinced of their rightness convinced to murder for the right? How did the January 6th insurrection fomented by a sore loser with revenge on his mind to punish his VP because he didn’t do what “was right” happen? Are there any elements that might be compared? This amazing play is filled with parallels to our time, as it raises profound questions about our humanity. For that reason, as well as the fine dialogue and overall presentation and ensemble work, one should see this play.

Here There Are Blueberries runs 90 minutes with no intermission at NYTW on 4th St. between 2nd and the Bowery. Don’t miss it.

‘Home,’ The Journey of a Lifetime in Wisdom and Poetry, Review

With lyricism and poignancy in this Roundabout Theatre Company revival of Home, directed by Kenny Leon, Samm-Art Williams spins a story of life’s rhythms, spanning decades during the Great Migration, the time when thousands of Blacks moved with hope to northern cities, leaving Jim Crow’s economic oppression and lynching violence behind. Williams’ covers distances and cultural spaces, all the while evolving his protagonist’s mental, physical and spiritual well being. Home has been receiving a “warm welcome,” at the Todd Haimes Theater, after a prolonged lapse since its original production in 1980 when it was Drama Desk and Tony-award nominated.

Starring Tory Kittles as Cephus Miles, newcomers Brittany Inge and Stori Ayers, portray a multiplicity of characters (40+) from family members to the men and women positively or negatively rubbing up against Cephus on his journey to self-realization. Williams’ representatives move us from a tobacco farm in Cross Roads, North Carolina to a prison in Raleigh, to a northern city (New York), of subways, a roiling, feverish, chaotic place for Cephus that spills out a never-ending cacophony of noise, colors, struggle and conflict.

Then finally, a battered, bruised and reformed drug and alcohol-addicted Cephus has had enough. By that point, he has died to his ego to return home to the rich black soil he thought he had lost, and God’s grace, which was apparently late in coming, but actually was with him all along.

It takes wisdom to know that God has been with him, which he has obviously gained as it is subtly expressed by the ersatz Greek chorus (Inge and Ayers), who introduce the theme of God’s grace which we and Cephus learn abides throughout his life. (“If there was ever a woman or man, who has everlasting grace in the eyes of God. It’s the farmer woman… and man.”) As Inge and Ayers repeat these affirmations as Woman Two and Woman One at the top of play and in a brief song and rhythmic summation of the life of the farmer/sharecroppers who labored and sweat under the sun, then left for the cities, they state that one “fool” came back. And Cephus, “the fool” sits in a rocking chair center stage listening to them.

Cephus, is anything but a fool. His travels have converted him to a contented man of wisdom who has learned, through patience, the hard lesson of God’s everlasting grace. Though we don’t realize it at the top of the play, Cephus has returned from his odyssey. The townspeople’s myths swirl around him (via Inge and Ayers), and town children (Ayers and Inge), whisper the rumors, “Old Cephus Miles. Can’t be saved,” that “he’s dead,” that “he’s a ghost,” as they throw rocks at the windows of the “haunted house,” where he has returned to claim “I’m alive,” “I’m flesh, blood and bone.”

The play is Cephus’ lyrical and dramatic life told in flashback, at times in and out of sequence, like an epic tone poem with the chorus (Ayers and Inge), at the ready to activate his narration, an exegesis exploring and explaining the spiritual text of the grace that threads through his life.

Against a backdrop of tobacco plants, corn stalks, golden lighting by Allen Lee Hughes and a projection of distant acres of crops to the horizon line (the projection changes when Cephus moves to the city), Leon employs a symbolic minimalism of set and props (set design-Arnulfo Maldonado). He adjusts scene changes based on the dialogue and simple objects, a box, a chair, a drop-down cross. Dede Ayite’s costumes and Ayers and Inge’s hair (Nikiya Mathis-hair & wig design), essentially remain the same with a few additions and subtractions (hats, scarves, hair let down-a wig). Miraculously, Leon’s simplicity which fits the thematic, lyrically flowing style of this work, is not only fitting, it is revelatory. However, it is also arcane and opaque at times.

Ultimately, Williams/Leon’s symbolic translation of Cephus’ seemingly “ordinary” existence becomes a spiritual guidepost that focuses on uplifting the souls of those who witness it. Thus, we gradually understand why Cephus quietly dismisses the extraordinarily horrid conditions of racism in the Jim Crow south. Slowly we realize how he withstands injustice related to his poverty and lack of education. That impact is demonstrated when Cephus, unlike those whites who paid to get bone spur deferments or were deferred by college, is drafted during the Viet Nam war. Many Blacks who were unable to get such deferments fought and died in the jungles. He reads the letters of two friends who warn him off going to fight.

But fear didn’t stop Cephus from serving. God’s commandment, “Thou shalt not kill,” stops him. A religious conscientious objector, he spends five years in prison because he refuses to kill in battle. After his imprisonment, Cephus gives up sharecropping and heads north. He has tethered his happiness to Pattie Mae, the love of his life, and thinks he may get an education and “improve” himself like she did. Her mother prompted her to go north, get an education, became a teacher and forget about marrying Cephus because she was “better” than he.

However, at this point in his life, destitute and without friends or shelter, somehow Cephus ends up in the city where life befalls him as he waits for God to “come back from Miami” and help him deal with countless issues. Life takes an unbelievable turn for him and he questions God’s absence. With humor Williams relates Cephus’ travails and shares stories out of the traditions of citified Black folk and stories from his country childhood, i.e. his time in the hayloft with Pattie Mae, gambling in the cemetery with friends, loss of close family members and more. Home presents the important and crucial moments in Cephus’ life under the long arm of God, who he prays to, sometimes.

Caught up in the emotionalism of his pain, Cephus, delivered in an incredible performance by Kittles, draws us in and keeps us engaged with humor bytes and memes that reoccur and have their final concluding day. The ending is more than a satisfactory relief and it is the first time we see Cephus grin from ear to ear. Indeed, he has come home in relating and reliving his journey with us with the dogged and wonderful supporting help of Inge and Ayers.

Williams’ style and poetic form is easy listening, as one catches the music inherent in the language and the word beats. At times, however, the pacing and lack of theatricality are uneven and I found myself drifting, despite the tremendous performances of the actors. Overall, the ensemble and their direction by Leon are smashing, as is Williams’ Homeric view which provides a look at war and battle in the human psyche filtered through the American Black experience.

This is one to see. Unless it is extended, the end date is July 21.

Home. Todd Haimes Theatre. 224 West 42nd Street with no intermission. https://www.roundabouttheatre.org/

Theresa Rebeck, Presented by League of Professional Theatre Women at NYPL for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center

Theresa Rebeck. If the name doesn’t sound immediately familiar, chances are you do know Theresa Rebeck’s work from Broadway, off-Broadway, television, films or literature. A prolific writer, she is the most produced female playwright of her generation. Her work is presented throughout the United States and internationally. Her Broadway credits include I Need That (starring Danny DeVito), Bernhardt/Hamlet (starring Janet McTeer), Dead Accounts (starring Norbert Leo Butz), Seminar (starring Alan Rickman), and Mauritius (starring F. Murray Abraham). Her off-Broadway productions are numerous.

It was a pleasure to hear and see her live in an event sponsored by the League of Professional Theatre Women, Monday, June 3, 2024 at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Lincoln Center’s Bruno Walter Auditorium. Interviewed by her close friend and producer Robyn Goodman (Avenue Q-Tony Award 2004, In the Heights-Tony Award 2008), Robyn founded Aged In Wood Productions in 2000. Their discussion was taped and is part of LPTW’s Oral History Project to preserve visual records of interviews of august women in the theater. The event was produced by director and producer Ludovica Villar-Hauser. A video of the event can be found in the Library’s TOFT Archive.

For the members of LPTW, Theresa Rebeck needed no introduction. Robyn Goodman began by asking general questions about Rebeck’s early life, and her background tie-ins to themes which often arise in her plays. This brief post focuses on a few salient highlights of the interview.

Born in Ohio, Rebeck grew up in an “ultra Republican, ultra Catholic” world. Receiving a Catholic education throughout, she graduated from Ursuline Academy in 1976 and continued with her Catholic education, graduating from the University of Notre Dame in 1980.

With irony and humor, Rebeck confided, “My parents didn’t want me to go to any East Coast School because they were afraid I’d lose my faith.” She shared that as a child, at times she went on a bus to see theater productions. Even at a young age, she venerated playwrights, thinking them gods. To her, Shakespeare, Moliere, Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams were fantastic. She joked that she was already into theater and drama before she got out of grade school.

After Rebeck began acting in earnest at Ursuline Academy, she told her mother “I think I want to be a playwright.” Rebeck got laughs when she joked about her mother’s response, “She turned grey.”

Interestingly, during her freshman year at Notre Dame, Rebeck was invited to a very religious group who was holding a prayer meeting. It was “really spooky,” and the people were “really religious.” Rebeck sensed something “dark and weird going on.” They were speaking in tongues and talking about women being subservient so that everyone “should know their place.” She quipped, “After ten minutes I wanted to go back to my dorm room.” However, she wasn’t sure how to get back.

This was an introduction to members of “People of Praise,” the religious community Supreme Court Justice Amy Cony Barrett has been a member of since birth. “People of Praise,” is associated with the Catholic charismatic renewal movement, but is not formally affiliated with the Catholic Church. Rebeck’s experience at the prayer meeting and listening to the group’s tenets sent her fleeing in the opposite direction. “People of Praise” appears to be unrepresentative of Rebeck’s Catholic upbringing which has well served her life and work.

As a tie-in, Robyn Goodman read a quote from the award-winning playwright Tina Howe (Coastal Disturbances, Pride’s Crossing), who died last year at 85-years old. Howe said of Rebeck that her “Catholic upbringing has had a profound imprint on her work,” and there’s “a moral heart to Theresa.” According to Howe, “She’s a force of nature who always carries her altar with her.”

When Robyn Goodman asked Theresa, “Do you see this in your work?” She responded, “I do.” Rebeck then grounded the history of theater with the idea of faith as an inherent meld. She claimed she is “one of those people” who thinks that the theater is “holy territory.” And she says of herself, “I’m always a person that points out that theater was a religious ceremony.”

In ancient civilizations the dance and tribal ritual and ceremonial presentation had a deep spiritual and religious basis. With the Greeks who allowed even the slaves to take off from work to participate, theater was a celebration of the god Dionysus, and there were annual play festivals and competitions. Rebeck suggested that in various cultures, there was the shaman or priest, and sitting right next to him was the playwright. For Rebeck, “The gathering of people to share stories and identify with the stories is powerful.”

In responding to Robyn Goodman’s question about her transformation to professional theater, Rebeck mentioned her first production was Spike Heels (1993), that Goodman produced at Second Stage Theater. It starred Kevin Bacon, Tony Goldwyn, Saundra Santiago and the great Julie White. “My husband was in it,” quipped Rebeck. Theresa is married to Jess Lynn, and together they have two children.

Goodman asked if the production and notoriety changed her life, especially the good reviews. Rebeck suggests that with the critics peppering her with questions, “It was like watching all the senators grilling Anita Hill.” One of the questions they asked, was, “Are you going to write a book?” Frank Rich compared Spike Heels to the film Pillow Talk. According to Rich, Kevin Bacon was Gig Young, etc.

Four months later, David Mamet’s Oleanna, which premiered in Cambridge, Massachusetts, appeared off- Broadway at the Orpheum Theater. Frank Rich reviewed it and Rebeck noted Rich’s review. He commented that after the Anita Hill-Clarence Thomas fiasco on Capitol Hill, “finally someone wrote a play about sexual harassment.” Rebeck’s response was tellingly frustrated. She shared her feelings about his comment. “Hey! You saw a play about sexual harassment written by a women and you didn’t notice.”

It was “a different time,” Rebeck said, as she discussed how she reacted to the male/female power issues. “You go along with it, get mad when you go home and try to discuss it, and you’re incoherent.” With Rich’s comment about Oleanna, Rebeck says,”I thought, ‘Come on, this isn’t about sexual harassment. This is a women lying about sexual harassment.'” Rebeck affirmed with Goodman that women were fighting for their place and stature at the time, so it was “very important to produce plays like that.” Rebeck suggested, “I was way ahead of my time,” which received an appropriate laugh.

Goodman pointed out another quote about Rebeck’s writing in that she often writes about “betrayal, treason and poor behavior, a lot of poor behavior.” To that Theresa agreed that many playwrights write about “poor behavior.” Goodman added that Rebeck also writes about class and power shifts.

Rebeck discussed her experiences with productions on Broadway and off-Broadway. In fact, she suggested that she began directing because after the effort and time spent writing a play, she got tired of the release process, after her initial involvement with the production. She went to the table reads, heard design presentations and answered questions people asked. Then came the “thank yous” and she would leave. Rebeck didn’t want to be at the side of “the main event.” She wanted total involvement.

She enjoyed working on Dig, which she also directed and which received wonderful reviews. “I’m so proud of it. It was a good experience.” It is important to Rebeck that the creators have work that they can claim as their own. She enjoys working collaboratively when people are respectful.

Goodman and Rebeck appear to have a shared view of how people negotiate successfully in the “real world.” They negotiate with a sense of morality. Goodman shared the quote which political parties, especially the Trump MAGA Party, eschew as anathema. “If you make the truth your friend, it can’t come and eat you alive.” Rebeck and Goodman agree that a clear, moral point of view in plays, musicals and literature is vital.

Theresa suggested that her alma mater Brandeis University also grounded her toward presenting a clear, moral point of view in her work. She received her three graduate degrees from Brandeis: her MA in English in 1983, a MFA in Playwriting in 1986, and a PhD in Victorian era melodrama in 1989. Fittingly, Rebeck pointed out, that on the seal of Brandeis University are the words, “Truth even unto its innermost parts.” The university president decided to surround the shield on the seal with the quote about truth which is from Psalm 51. Rebeck noted that she recognized the seal on the podium (though it wasn’t clear at that point that it was Brandeis), hearing/seeing a clip of Ken Burns deliver his trenchant Keynote Address to Brandeis University’s 2024 undergraduate class during the 73rd Commencement Exercises. If you haven’t heard any of his speech, you can find it on YouTube. It is definitive and acute.

Rebeck affirms that “writing plays is about people” in the hope to understand “human brilliance and failure.” Of course at times there’s “political content.” However, at the heart it’s about people and human behavior.

In responding to Goodman’s question related to critics, Rebeck agreed that sometimes reviews are devastating and that her husband goes through the process with her. She mentioned that there can be five wonderful or enlightening critiques, and then there is the “crazy” review which is off kilter and seemingly out of nowhere, and people are “foaming at the mouth.” Sometimes, there is that one review while other critics and audiences love the work.

At one point Rebeck thought, “Why do they hate me?” Then, she realized if there’s one outlier, then there isn’t coherence. She mentioned that for a long time people only cared about and quoted the “paper of record.” Of course the irony was that there were many different critics and opinions. The diverse voices and viewpoints are exciting and especially vital for our time. That one opinion held sway and could make or break a play was “damaging to the psyche of the community.” She affirmed, “Now, it’s less dire.”

Rebeck spoke of an incident with a young producer who acted as if there was only one paper that mattered, historically, the “paper of record.” This individual said, based on one review, “Well, the reviews were bad.” Rebeck gave them a reality check. She said that a producer should never act like there is one reviewer who speaks for all critics. To obsess about one review is to bury oneself in negativity and recriminations. She told the producer, “Don’t do that!”

Indeed, Rebeck’s point is well taken. Historically, other critics bought into the prestige factor of “the paper of record,” denigrating their own voices and viewpoints, and bowing to the one review that allegedly spoke for all critics. In this day of book bannings, culture wars and rewriting history, such an approach is tantamount to critics mentally censoring themselves as inferiors. If there is a consensus about a play, that speaks volumes. One “determination” by one critic, regardless of how much he or she is paid, shouldn’t be the “word from on high” that the critics, theater professionals or the public “should” listen to and take to heart.

Rebeck and Goodman are expanding their winning teamwork. They’ve joined together on the musical Working Girl, based on the titular1988 Twentieth Century Fox motion picture written by Kevin Wade. Aimed for Broadway, the musical is presented by special arrangement with Buena Vista Theatrical. Writing the book, Rebeck discussed how she loves working with Tony-winning, composer-lyricist Cyndi Lauper (Kinky Boots), who is writing the score. Tony winner Christopher Ashley (Come From Away) is directing. Producers include Goodman and Josh Fiedler of Aged in Wood Productions, and Kumiko Yoshii.

Rebeck created Smash for NBC and briefly discussed a few highs and lows of working on the showbiz dramatic series. She liked Stephen Spielberg. Since Smash, she has been especially enamored of musical theater. Working Girl is a project that involves collaboration. To have to write a play singularly and then give it to a composer and lyricist is something Rebeck wasn’t interested in doing. She and the team are reimagining and updating the classic. It’s an exciting approach because it also emphasizes women working together and supporting each other on their “climb to the top.” With the political climate as it is, the musical is profoundly important.

One of the themes of the evening was that especially after COVID-19, theater has changed. Theaters around the country are in deep financial trouble. Robyn Goodman suggested that Broadway has gotten out of hand. The business is completely different than what it was two decades ago. Now, to mount a production viably, it costs $25 million dollars. It’s all about the money and finding backers.

As for budding playwrights, Rebeck advised that festivals are a good venue as a place to begin and get noticed. Indeed, 10 minute play festivals allow the creative team to put on “a beautiful event” for little or no money. One can even write a short one-act play and submit it to a one-act play festival. This is a boon for the playwright, who needs to learn how the process works and see the audience’s response to the play. That is an imperative for beginning playwrights.

Rebeck’s plays are published by Smith and Kraus as Theresa Rebeck: Complete Plays, Volumes I, II, III, IV and V. Acting editions are available from Samuel French or Playscripts. For a complete listing of all of her work you can find Theresa Rebeck on her website: https://www.theresarebeck.com/ Robyn Goodman’s website is https://www.agedinwood.com/about

Visit The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, the Library’s TOFT Archive to see the digital recording of the evening. For more information about the TOFT Archives, see this link. https://www.nypl.org/locations/lpa/theatre-film-and-tape-archive To learn more about LPTW, check out their website. https://www.theatrewomen.org/

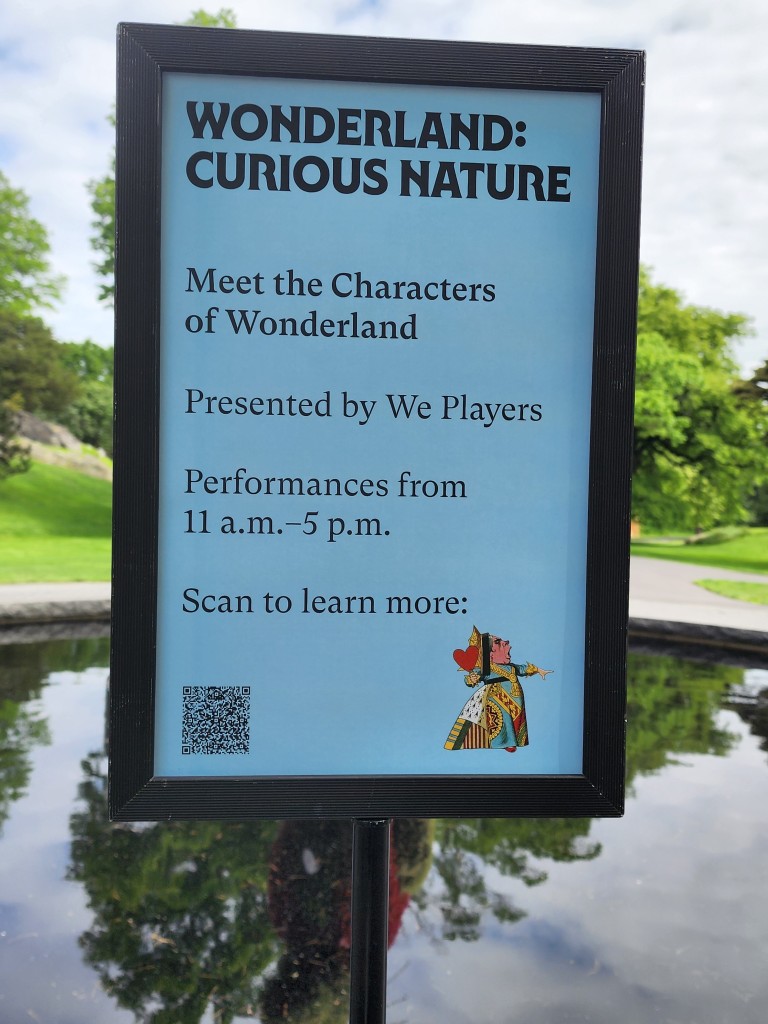

‘Wonderland: Curious Nature’ at New York Botanical Garden

Victorian “Age of Wonder,” Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, a Fascinating Exhibit

NYBG opened its latest exhibit this weekend. Inspired by the classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and the sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, And What Alice Found There, by Lewis Carroll, the all-new garden-wide exhibition is whimsical and full of fun and surprising features.

Today, Sunday is the Opening Weekend Garden Party Celebration from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Daffodil Hill. You can dine as a special guest at the Queen’s Tea. And you can encounter The Mad Hatter, Alice, the Red Queen, and other Wonderland characters popping up on the walkways throughout the Garden.

OPENING WEEKEND GARDEN PARTY CELEBRATION TODAY, SUNDAY, MAY 19

Today, May 19, Sunday, there are lawn games like croquette, and other craft activities. Or if you prefer to meditate and reflect as you relieve the stresses of a hard work week, just enjoy a self-guided tour following the digital signs as you appreciate the Garden in its glorious pageantry in the spring. Everywhere you look there is a plant wonderland and themes from Carroll’s works and the Victorian era’s new age of exploration and wonder.

And as you are swept up in the Garden’s heavenly beauty you just may see a Cheshire Cat grinning out at you, for real. Certainly, if you let go, that Cheshire is there smiling at your happiness that you’ve treated yourself and your family to the Garden’s fantastical retreat.

Follow the Signs

Plants Inspired by Oxford Botanical Gardens, Where Lewis Carroll Walked

The Wonderland Exhibit continues at LuEsther T. Mertz Library. Visit the galleries to see the contemporary global artists, i.e. Abelardo Morell, Beverly Semmes, Agus Putu Suyadnya and others inspired by Carroll’s books. There are artworks reflect the global appreciation of the wacky characters and settings found in Alice’s Adventures. And in the rotunda of the Library look at the exhibit of dried mind-altering plants, their descriptions, and the songs and books they inspired which reference Carroll’s work. Some of these plants like opium and various mushrooms promoted altered states. The plants influenced Carroll’s idea about perception that he incorporated in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, And What Alice Found There.

Wonderland: Curious Nature runs until October 27, 2024

The events run from this weekend through October 27th across three seasons, spring, summer and fall. There are programs for the entire family and even the characters from the fantastical books by Lewis Carroll show up to entertain and frolic down the Garden’s pathways always ready for a photo or chat with the more serious patrons wanting to find out more about the characters they portray.

Wondrous people and plants.

Look out for unusual characters and unusual plants that enjoy a marriage with insects like the fern below.

Wonderland: Curious Nature is not only fun, it is ingenious. From the spectacular flower show in the main galleries of the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory to the scheduled tea parties and brunches in the Stone Mill near the Peggy Rockefeller Rose Garden and different menu offerings at the Hudson Garden Grill, there is something for everyone. I will update the exhibit coverage in weeks to come.

For specific programming, go to the New York Botanical Garden site: https://www.nybg.org/event/wonderland-curious-nature/wonderland-curious-nature-programs/wonderland-curious-nature-opening-weekend/

‘Staff Meal,’ Avant Garde, Experimental, a Review

In the notes from playwright Abe Koogler about Staff Meal, directed by Morgan Green, currently at Playwrights Horizons, Koogler hopes that the audience, “will emerge from it the way you might emerge from a transportive meal in an unusual restaurant in a part of town you’ve never been to before. The avant garde work, shrouded with a uncertainty is most interesting when there appears to be a linear forward movement among characters during vignettes of scenes which take place in Gary Robinson’s restaurant, that once was packed, but by the end closes down.

At the top of the play Ben (Greg Keller) and Mina (Susannah Flood), sit near each other in a coffee shop working on their laptops. Eventually, their proximity prompts them to become familiar with each other so after a number of days, saying “Hi,” and other chatty comments, they leave and seek better coffee and/or food elsewhere. The search leads them to Gary Robinson’s restaurant.

The rapport and pacing between Keller and Flood is enjoyable and funny by these talented actors. However, it ends when they get bogged down ordering from a waiter who takes an inordinately long period of time to take their order and bring back an excellent wine. In the interim, they take humorous and sobering flights of fancy about their personal lives which include some of the most imaginative dialogue in the play. However, when the waiter has not brought their food, then the scene shifts with the mood, and the focus becomes their waiter and his experience at the restaurant.

As a flashback of “The Waiter” segment begins, Ben and Mina leave “hanging in the air,” the thread of dialogue along with Ben’s story about his dog, whom his parents mistreated during the time he lived with his family in Spain. Hampton Fluker is the waiter who enters the spotlight. He discusses his time at the restaurant joined by other members of the wait staff (Jess Barbagallo, Carmen M. Herlihy), and chef Christina (Erin Markey), who serves them their delicious “staff meal” before they begin the evening’s service. Fluker’s waiter declines the meal at this point because it is his first day and he is afraid he will throw up out of nervousness.

What is striking about this vignette is that Christina doesn’t come up with ordinary food for the staff, but serves them extraordinary dishes following the philosophy of Gary Robinson, who emphasizes the importance of being of service to others. As one of the servers affirms, “Our power, our glory increases only so much as we give it away, constantly, only so much as we serve.” This is akin to a Biblical verse which implies, if one would be a great leader, one must be great at serving others. This philosophy is the antithesis of that practiced by politicians who serve themselves first, last and always, a virus that has particularly attacked the former Republican Party known as the Trump MAGAS.

However, like fragments of wisdom and truth which filter in and out of our consciousness, this conversation among the staff as they eat Christina’s delicious food and reference two of Gary Robinson’s books, dissolves into the air, though it is a profound concept that is incredibly current. However, one of the reasons why this wisdom and the astute servers’ conversation comes to a screeching halt is that an audience member interrupts with an important question, akin to “What the hell?”

By this point in time, the fourth wall has been broken twice; first by a vagrant (Erin Markey), who attempted to steal Mina’s laptop, though Mina elicited the help of an audience member to watch it for her when she went to the bathroom, because Ben wasn’t there that day. Luckily, Mina interrupts The Vagrant’s theft and sends her away without the laptop as Mina chides the negligent audience member, who was obedient to the playwright and didn’t tell The Vagrant, “Stop thief!”

The second breaking of the fourth wall is by a disruptive “audience member” (the fine Stephanie Berry), who is “annoyed” and questions the direction of the play defining it as meaningless, unrelated to her life, not current-when the world is burning down, and a waste of the gift of the audience’s time. Joining the other actor/servers onstage, she then discusses what she considers meaningful, her life, and the direction it has taken recently.

Of course, this is humorous and gives way to the notion that audience members’ opinions don’t always jive with theater professionals, though they can make or break them via word of mouth recommendations. Then the playwright forestalls audience opinions about his avant garde, surrealistic, weird work, using Berry as a a mouthpiece when the playwright has her say, “Do you ever get this feeling with young writers, or early writers, writers who are developing….do you ever wonder: when will they develop?” Berry’s audience member excoriates the quality of the play, Staff Meal, addressing the characters and absent playwright before sharing what is relatable to her in her life.

On consideration this surreal vignette works because of Berry’s authentic, spot-on performance which is confessional and makes us empathize with her even more so than with the other vignettes. But then she leaves and Koogler picks up where he left off back to the servers discussing the dwindling clientele and whether or not Robinson is going to close the restaurant down.

Then time and space shift once more. At this point, the servers and the couple have disappeared and the vignette with The Vagrant (Erin Markey) occurs. She explains that she takes on three roles, one of which is the chef, but the segment of The Vagrant involves her living in a hole and trying to acquire laptops so that she can get a job. Ah ha! We have the explanation of The Vagrant attempting to steal Mina’s laptop early on in the play. Eventually, she goes for a job interview and is hired and tells us she lived an extraordinary ordinary life and concludes with her affirmation that the rest of the play is about “how it ended.”

Berry’s audience member returns, warning us that she has been found out to be an artifice, and her role in the play is over, but she notices the weather outside is shifting and becoming ominous. The time has shifted once more and events move toward an unsettling conclusion. However, we do find out what happened to Ben’s dog, after they leave the restaurant without their food or wine. The waiter receives a delectable “staff meal,” Ben and Mina are separated walking home, and The Waiter is left questioning if Christina is still in the restaurant.

At this juncture it’s time to reconsider the audience member/playwright twitting himself about what he’s written. However, the play is more naturalistic in its chaotic, unthreaded, seeming randomness with bits of profound meaning stuffed here and there, like life, perhaps. In that we realize that we make meaning from our own lives, as random and strange as events can sometimes be, which have no rhyme or reason. Indeed, a fictional play with a neat beginning, middle and ending is easy to follow, but is perhaps easily dismissed as fiction. Staff Meal, as surreal as it is, is darkly memorable.

To assist with the sets which dissolve away to a bare stage, Jian Jung’s minimalist scenic design creates a cafe, a kitchen, a restaurant dining room and the dark ominous streets. Additional kudos go to Kaye Voyce’s simple (costume design), though I thought the elaborate costume for The Vagrant was interestingly layered with various “stuff.” Masha Tsimring (lighting design), kept segments toward the end foreboding, and Tei Blow (sound design) and Steve Cuiffo (illusion design), executed Morgan Green’s vision for Staff Meal.

Staff Meal will keep you guessing and wondering and perhaps as annoyed as Stephanie Berry’s Audience Member, trying to find the portal to understanding what’s beyond this unusual restaurant that serves its staff better than its customers. It runs with no intermission at Playwrights Horizons, Peter Jay Sharp Theater, 416 West 42nd Street. https://www.playwrightshorizons.org/shows/plays/staff-meal/

‘The Great Gatsby,’ Sumptuously Re-imagined, A Must-See, Unforgettable Broadway Spectacle

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald is an iconic American novel set during the Jazz Age. It is about class, the privilege of old wealth and the excesses of the nouveau riche, who can never attain the status of the generational moneyed class, regardless of how hard they try. The Great Gatsby a New Musical, based on the titular novel, retains this key theme of America’s class system from the perspective of unreliable narrator Nick Carraway (Noah J. Ricketts). Carraway memorializes Jay Gatsby, the extraordinaire, whose ability to distill hope and materialize his dreams achieves its own artistic perfection. Examined from the perspective of Nick Carraway (Noah J. Ricketts), the tragic flaw in Gatsby’s process is that he attaches his hope to the imperfection of love and a woman who wasn’t worthy of his vision, faith or love.

The Great Gatsby, a New Musical made its premiere at the Broadway Theatre after its fall run at the Paper Mill Playhouse in New Jersey. With book by Kait Kerrigan in her Broadway debut, music by Jason Howland (Paradise Square), and lyrics by Nathan Tysen (Paradise Square), the musical is suprbly choreographed by Dominique Kelley and acutely directed by Marc Bruni (Beautiful: the Carole King Musical). Overall, it’s a gorgeously conceived production with exceptional ensemble work and flamboyant spectacle that sumptuously re-imagines the distinctive settings, individualistic characters and seminal events that make the novel a singular and timeless classic.

The strength of this production is that Kerrigan, Howland and Tysen are loyal to Nick’s perception of the magnificent Jay Gatsby, portrayed exquisitely by Jeremy Jordan. Jordan’s luscious, exceptional voice, Gatsbyesque persona, and passion do justice to Howland and Tysen’s lyrical and dynamic songs, “For Her,” “Past Is Catching Up to Me,” and the duet “Go.” We empathize with Jordan’s Gatsby, whose near divine love of Daisy (the lovely Eva Noblezada), never fails him, though Daisy can’t handle the irrepressible and divine nature of his efforts to transform time.

In “My Green Light,” an extraordinary duet between Noblezada and Jordan at the end of Act I, the couple consummates their love in Gatsby’s lavish bedroom with the projection of the rippling Long Island Sound at night, and the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock twinkling behind them in the background.

Bruni’s phenomenal staging, Paul Tate DePoo III’s projection and set unifies the key elements of the love relationship between Gatsby and Daisy, the artistry of Gatsby’s vision and his infinite hope (symbolized by the green light), driving it. The acting talents of Jordan and Noblezada, their lustrous singing and the setting are dazzling in this memorable, uplifting scene, where Gatsby, indeed, for a moment conquers time.

At that point we believe that Gatsby’s love is enough to hold Daisy and take her away from the craven, brutish, hypocritical Tom, who breaks his mistress Myrtle’s nose (Sara Chase), and manhandles Daisy leaving bruises on her arms during their quarrels. We believe like Nick and Jordan (the adorable Samantha Pauly), that Tom doesn’t deserve Daisy. However, by the conclusion of the musical, Nick realizes that Tom and Daisy do deserve each other. She won’t even attend Gatsby’s funeral, acting like he never existed. We agree with Nick that Gatsby is “worth the whole damn bunch put together.”

As Nick spins it, the tragedy lies in Daisy’s soulish weakness and her inability to live up to Gatsby’s love to “forget the past,” which he asks her to do in front of Tom in the superbly acted scene at the Plaza Hotel. Together the characters sing the sensational ensemble number “Made to Last.” John Zdrojeski’s Tom is particularly cruel as he arrogantly denounces Gatsby, his criminal bootlegging and his low class background. The lyrics are profound and spot-on. The dynamic music reinforces the themes which the characters forcefully embrace and symbolize. Tom sardonically sings, “It’s not about wealth, it’s blood. It’s class. The day you were born, your die had been cast.” And Gatsby insists, “Daisy, tell him you’re through.” And he tells Tom to “face reality,” affirming that Daisy never loved Tom.

During the explosive turning point in the song, Gatsby insists she renounce her marriage to Tom, and in effect her position and class to which Tom “elevated” her. When Tom sees she falters, that she honestly admits that she loved them both, and that Gatsby “wants too much,” Tom feels secure. He knows she is too weak and insecure to leave him and their daughter. Noblezada’s Daisy, Zdrojeski’s Tom and Jordan’s Gatsby strike the mixture of emotions of their characters with authenticity and power. Daisy’s heightened angst and tenuous state of mind force her to leave the suite, with Gatsby running after her. It is not a position of power from which Gatsby might redeem himself with her, though he tries.

Tom’s defamation and insults to Gatsby’s face and the reality of what Daisy would be giving up to leave him dislocates Daisy to distraction and ultimately causes the fatal accident and final tragedy of the underclasses, who make the mistake of becoming involved with the soulless, unimaginative upper class.

Noblezada portrays Daisy’s confusion with grist, making Jeremy Jordan’s desperation to stop Tom’s brainwashing and win her back even more pronounced. When Tom’s words hit their mark, it’s as if a curtain shuts down Daisy’s mind. Jordan’s Gatsby sees the impact of Tom’s cynicism as it disintegrates all the romance of what he has accomplished in order to turn back time to the fullness of Daisy’s love when Tom never existed. The scene is the brilliant high-point. What follows is the aftermath from which there is no recovering, except that Nick must lead the musical encomium to the greatness of his friend Gatsby. He alone fully grasps who the man was, so of course, he is furious that the papers slam Gatsby and further drive Daisy into oblivion and Tom into victory, as they jaunt away to Hawaii.

Kerrigan, Howland and Tysen are faithful to the key events in the novel down to no one going to Gatsby’s funeral except Nick which Bruni simply stages with black curtains, the casket and bier and red roses. Howland and Tysen fill out Wilson’s mania as he assassinates Gatsby, after Tom sets him up (“God Sees Everything”). As Gatsby sings the reprise “For Her” and Nick imagines how it happens, Wilson joins in and asks God’s forgiveness for using his hands to met out justice and take responsibility for the execution. Of course, Wilson’s ask is ridiculous as his justice is misplaced. Duped by Tom to do violence and pay for it with his own life, Wilson is a pathetic figure. Reflecting on these events, and Daisy and Tom’s nonchalance about Gatsby and the Wilsons, Carraway disdains Daisy and Tom as representative of the careless rich who destroy people and things leaving the Nick Carraways of the world to clean up the mess.

Comedic elements are found in this adaptation which sometime diffuse the impact of the story, as does attention to the secondary characters who are given greater focus. It is also problematic that Nick’s perspective doesn’t cohere throughout the musical, but leaves off in a few scenes, one between Jordan and Daisy.

Some of the comedy is refreshing as in the scene Nick and Jordan share at Nick’s cottage while Daisy and Gatsby meet for the first time in five years. Their relationship is expanded beyond the novel when Jordan and Nick’s intimacy gives way to his proposal of marriage which she is on the verge of accepting, though in Act I she is against marriage. Her characterization is more in keeping with today’s women than women of the early 20th century. Nick’s characterization is largely faithful to the novel. Noah J. Ricketts does a fine job of rendering Nick the unreliable narrator who thinks highly of himself, but doesn’t completely stand up to Tom and Daisy. Instead, he turns tail and runs back to the Midwest away from the” “evil” East, an irony. The only way he can reconcile his self-loathing about his behavior is to attempt to expiate his guilt by memorializing Gatsby.

The Jordan/Nick scenes are humorous and flirtatious. Their number “Better Hold Tight” is a diversion more for its own sake. However, we are not surprised that Nick throws over Jordan who doesn’t show up to Gatsby’s funeral either. She is one of the bad drivers, the careless rich who sicken and disgust him, for they dupes the fools who would seek the dream “boats running against the current” (“Finale: Roaring On”), to only to stumble because their dreams are behind them in the past.

Kerrigan, Howland and Tysen take even greater liberties with the secondary characters for the sake of dramatic purposes. Kerrigan, et. al. strengthen and coalesce the ideas symbolizing George Wilson (Paul Whitty), George’s wife Myrtle (Sara Chase), and Meyer Wolfsheim (Eric Anderson), by giving each of them solo numbers which define their personalities, desires and attitudes. These add to the themes, though they refocus the thrust of Nick’s story of how Gatsby is a romantic hero. The mystery surrounding Gatsby’s identity which is slowly revealed in the novel, is lost in this musical with attention going elsewhere.

As a representative of the criminal class that feeds the dreams of the lower class, breaking the law to do so, thug Wolfsheim joins the company singing “New Money,” which old wealth (Tom), regards as garish and meretricious. Anderson’s Wolfsheim (“who made Gatsby”), also sings and joins the company dancing in the excellent number “Shady.” As Wolfsheim sings, Bruni stages vignettes with each of the character couples being corrupted in their adultery or “sinful” affairs (Jordan and Nick, Gatsby and Daisy, Tom and the Wilsons). According to Wolfsheim, “I’m okay with keeping secrets. I’m okay with being naughty. I approve of indiscretions, if you know how to hide a body.”

Eric Anderson and cast of The Great Gatsby (Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

Read the rest of this entry

‘Uncle Vanya,’ Steve Carell in a Superb Update of Timeless Chekhov

A favorite of Anton Chekhov fans is Uncle Vanya because it combines organic comedy and tragedy emerging from mundane, static situations, intricate, suppressed characters and their off-balanced, mired-down relationships. Playwright Heidi Schreck (What the Constitution Means to Me), has modernized Vanya enhancing the elements that make Chekhov’s immutable work relevant for us today. Lila Neugebauer’s direction stages Schreck’s Chekhov update with nuance and singularity to make for a stunning premiere of this classic at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont in a limited run until June 16th.

With a celebrated cast and beautifully shepherded ensemble by the director, we watch as the events unfold and move nowhere, except within the souls of each of the characters who climb mountains of elation, fury, depression and despair by the conclusion of this two act tragicomedy.

Schreck has threaded Chekhov’s genius characterizations with dialogue updates that are streamlined for clarity, yet allow for the ironies and sarcasm to penetrate. At the top of the play Steve Carell’s Vanya is hysterical as he expresses his emotional doldrums at the bottom of a whirlpool of chaos which has arrived in the form of his brother-in-law, Professor Alexander (the pompous, self-important Alfred Molina in a spot-on portrayal), and Alexander’s beautiful, self-absorbed, younger-by-decades wife Elena (Anika Noni Rose). Also present is the vibrant, ironic, self-deprecating, overworked Dr. Astrov (William Jackson Harper), a friend who visits often and owns a neighboring estate.

During the course of the first act, we are witness to the interior feelings and emotions of all the characters who in one way or another are bored, depressed, miserable and disgusted with themselves. Vanya is enraged that he has taken care of Alexander’s lifestyle, even after his sister died in deference to his mother, Maria (Jayne Houdyshell). He is particularly enraged that he believed with is mother that Alexander was a “brilliant” art critic who deserved to be feted, petted and over credited with praise when he lived in the city.

Having clunked past his prime as an old man, Alexander has been fired because no one wants to read his work. He and Elena have run out of money and are forced to stay in the family’s country estate with Vanya and Sonia, Alexander’s daughter (the poignant, heartfelt Alison PIll), away from the limelight which shines on Alexander no more. Seeing Alexander in this new belittlement, though he orders around everyone in the family, who must wait on him hand and foot, Vanya is humiliated with his own self-betrayal. He didn’t realize that Alexander was a blowhard who duped and enslaved him to labor on the farm to supporting his high life, while he pursued his “important” writing. Vanya and Sonia labor diligently to make sure the farm is able to support the family, though it has been a difficult task that recently Vanya has grown to regret. He questions why he wasted his years on a man unworthy of his time and effort, a fraud who knows little about art.

Likewise, Astrov questions his own position as a doctor, admitting to Marina (Mia Katigbak), that he feels responsible for not being able to help a young man killed in an accident. To round out the “les miserables,” Alexander is upset that he is an old man who is growing more decrepit by the minute as he endures believing his young, beautiful wife despises him. Despite his upset, Alexander expects to be waited on by his brother-in-law, mother-in-law and in short, everyone on the estate, which he has come to think is his, by virtue of his wanting it. Though the estate has been bequeathed to his daughter Sonia by Vanya’s sister, his first wife, Alexander and Elena find the quiet life in the country unbearable.

As they take up space and upturn the normal routine of the farm, Elena has been the rarefied creature who has disturbed the molecules of complacency in the lives of Vanya, Sonia and Astrov. Her beauty is shattering. Sonia hates her stepmother, and both Vanya and Astrov fall in love and lust with her. As a result, their former activities bore them; they cannot function with satisfaction, and have fallen distract with want, craving the impossible, Elena’s love. Alexander fears losing her, but realizes if he plays the victim and harps on his own weaknesses of old age, as distasteful as he is, Elena is moral enough to attend to him, though she is bored and loathes him in the process.

The situation is fraught with problems, hatreds, regrets, upsets and soul turmoil, which Schreck has stirred following Chekhov’s dynamic. Thus, Carell’s Vanya and Harper’s Astrov are humorous in their self-loathing as is the arrogant Alexander and vapid Elena who Sonia suggests can end her boredom by helping them on the farm. Of course, work is not something Elena does, which answers why she has married Alexander and both have been the parasites who have sucked the lifeblood of Vanya and Sonia, as they labor for their “betters,” who are actually inferior, ignoble and selfish.

To complicate the situation, Sonia is desperately in love with Astrov, who can only see Elena who is attracted to him. However, Elena is afraid to carry out the possibility of their affair. Instead, she destroys any notion that Sonia has of being with Astrov by ferreting out Astrov’s feelings for Sonia which tumble out as feelings for Elena and a forbidden, hypocritical kiss which Vanya sees and adds to his rage at Elena’s self-righteousness and martyred morality. When Elena tells Sonia that Astrov doesn’t love her, Sonia is heartbroken. It is Pill’s shining moment and everyone who has experienced unrequited love empathizes with her devastation.

When Alexander expresses his plans to sell the estate and take the proceeds to live in the city in a greater comfort and elegance, Carell’s Vanya excoriates Alexander and speaks truth to power. He finally clarifies his disgust for the craven and selfish Alexander, despite Maria’s belief that Alexander is a great man, not the fraud Vanya says he is.

It is a gonzo moment and Carell draws our empathy for Vanya who attempts to expiate his rage, not through understanding how he is responsible for being a dishrag to Alexander, but through manslaughter. The scene is brilliantly staged by Neugebauer and is both humorous and tragic. The denouement happens quickly afterward, as each of the characters turns to their own isolated troubles with no clear resolution of peace or reconciliation with each other.

The ensemble are terrific and the actors are able to tease out the authenticity of their characters so that each is distinct, identifiable and memorable. Naturally, Carell’s Vanya is sympathetic as is Pill’s heartsick Sonia, for they nobly uphold the ethic that work is a kind of redemption in itself, if dreams can never come true. We appreciate Harper’s Astrov in his love of growing forests and his understanding of the extent to which the forests that he plants will bring sustenance to the planet, if even to mitigate only somewhat the society’s encroaching destructiveness. Even Katigbak’s Marina and Sonia’s godfather Waffles (the excellent Jonathan Hadary), are admirable in their ironic stoicism and ability to attempt to lighten the load of the others and not complain.

Finally, as the foils Molina’s Alexander and Noni Rose’s Elena are unredeemable. It is fitting that they leave and perhaps will never return again. The chaos, misery, dislocation and confusion they leave in their wake (including the somewhat adoring fog of Houdyshell’s Maria), are swallowed up by the beautiful countryside and the passion to keep the estate functioning which Sonia and Vanya hope to achieve in peace. Vanya, for now, has thwarted Alexander, by terrorizing Alexander into obeying him in a language (threatening his life), he understands. For this we applaud Vanya.

When Alexander and Elena leave, the disruption has ended and they take their drama and chaos with them. It is as if they were never there. As Vanya and Sonia handle the estate’s paperwork, which they’ve neglected having to answer Alexander’s every need, the verities of truth, honor, nobility and sacrifice are uplifted while they work in silence, and peace is restored to the estate, though they must suffer in not achieving the desires of their lives.

Neugebauer and Schreck have collaborated to create a fine version of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya that will remain in our hearts because of the simplicity and clarity with which this update has been rendered. Thanks go to the creative team. Mimi Lien’s set design functions expansively to suggest the various rooms of the estate, the garden and hovering forest in the background. A decorative sliding divider which separates the house from the forest and allows us to look out onto the forest and woods beyond (a projection), symbolizes the division between the natural and the artificial worlds which influence and symbolize the characters and what they value.

Vanya and the immediate family take their comforts from the earth and nature as does Astrov. Alexander and Elena have forgotten it, finding no solace in the beautiful surroundings and quiet, rural lifestyle which they find boring because they prefer chaos and the frenetic atmosphere of society. Essentially they are soul damaged and need the distractions they’ve become used to when Alexander was famous and the life of the party before he got tiresome and old and disgusting in the eyes of Elena and those who fired him..

The projection of trees that expands entirely across the stage in the first act is a superb representation of what is immutable and must be preserved as Astrov works to preserve. The forest of trees which is the backdrop of the garden, sometimes sway in the wind. The rustling leaves foreshadow the thunder storm which throws rain into the garden/onstage. The storm symbolizes the storm brewing in Uncle Vanya about Alexander, and emotionally manifests when Alexander suggests they sell the estate to fulfill his personal agenda.

During the intermission every puddle and water droplet is sopped up by the tech crew. Kudos to Lap Chi Chu & Elizabeth Harper for their lighting design and Mikhail Fiksel & Beth Lake for their sound design which bring the symbolism and reality of the storm home.

The modern costumes by Kaye Voyce are character defining. Elena’s extremely tight knit, brightly colored, clingy dresses are eye candy for her admirers as she intends them to be to attract their attention, then pretend she doesn’t want it. Of course she is the leisurely swan while Sonia is the ugly duckling in work clothing, Grandmother Maria dresses like the “hippie radical feminist” that she is, and Marina is in a schmatta as the servant who cooks and cleans. Here, it is easy for Elena to shine; there is no competition.

Vanya looks frumpy and uncaring of himself. This reflects his depression and lack of confidence, while Molina’s Alexander is dressed in the heat like a peacock with a scarf, cane and hat and cream-colored suit when we first see him. Astrov is in his doctor’s uniform, utilitarian, purposeful, then changes to more relaxed clothing. The costumes are one more example of the perfection of Neugebauer’s vision and direction of her team.

Uncle Vanya is an incredible play and this update does Chekhov justice. It is a must-see for Schreck’s script clarity, the actors seamless interactions and the creative teamwork which elevates Chekhov’s view of humanity with hope, sorrow and love in his characterizations, especially of Vanya.

Uncle Vanya runs two hours twenty-five minutes including one intermission, Lincoln Center Theater at the Vivian Beaumont. https://www.lct.org/shows/uncle-vanya/whos-who/

‘Mother Play,’ Stellar Performances by Celia Keenan-Bolger, Jessica Lange, Jim Parsons

One of the keys to understanding Mother Play, A Play in Five Evictions by Paula Vogel is in the narration. Currently running in its premiere at 2NDSTAGE, directed by Tina Landau, Vogel’s play has some elements of her own life, but is not naturalistic. It is stylized, quirky, humorous, imaginative and figurative, like most of her plays. In a nod to Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie, in the notes, she suggests it is a memory play.

Presumably, the play focuses on a representative mother, Phyllis, portrayed with impeccable sensitivity, raw emotion and nuanced undercurrents of bitterness, humor and irony by the exceptional Jessica Lange. However, the play is actually about a mother-daughter relationship that moves toward reconciliation. As such, the narrator/daughter (the always superb Celia Kennan-Bolger), directs us to her understanding of the last forty years of her life in her relationship with her mother, via the unreliable narrator’s viewpoint.

Should we believe everything the narrator says happened? Or does Martha’s perception of her mother cling to highlights of the events most hurtful and damaging to her? We must ultimately decide or remain uncertain until the play’s conclusion. It’s a delicious conundrum that emphasizes Vogel’s themes of the necessity of developing a deeper understanding of relationships, emotional pain, working through hurt and so much more.

Martha’s genius gains our confidence, empathy and identification with her confessional re-enactment flashbacks as she remembers events. She takes us through the highs and lows of five evictions her family experiences together, after their father dumped them for greener pastures. A key figure in the family dynamic is her two-years older brother Carl, Martha’s brilliant, sweet and kind protector, portrayed with clarity, humor and depth by Jim Parsons.

At the top of the play, which is in the present, Martha is in her early 50s. She tells us that by the time she was 11, their family had moved seven times because their father had a “habit of not paying rent.” Thus, they learned to pack and unpack in a day. She comments with irony that there is a season for packing and a season for unpacking, referencing the Biblical verse (Ecclesiastes 3:1-8), and the Byrd’s song, “Turn, Turn, Turn.”

To destabilize and uproot children from their friends and school mates so many times is a calculation Vogel’s Martha never makes. But it speaks volumes about how the brother and sister rely on each other emotionally, because they are social isolates by necessity because the continued movement which their father, whom we only hear about, didn’t even take into consideration.

As Martha opens a box of the only things her deceased brother had left in their apartment, she takes out a bunny rabbit and a letter Carl had written to her. With the letter, Parson’s Carl materializes and Martha joins him as they step into a series of flashbacks which chronicle events that lead to the five times they were evicted by landlords or they evicted themselves from each other’s lives, only to return, eventually.

Cleverly grounding this family’s living arrangements to present her salient themes about “forever pain,” the impossibility of “mothering,” sacrifice, regret and love, Vogel uses two devices. The first is their furniture which they take with them and rearrange each time they pick up and take off for various reasons. Secondly, there are the roaches, which are magical and symbolic, not only of the poverty and want their father stuck them with, but of the emotional terror and fear of living precariously on the edge of society, sanity and Phyllis’ desire for normalcy.

The roaches, at key moments manifest, swarm, go creepy crawly and loom monstrously in their lives. Since Phyllis signs leases to cheaper basement apartments, promising they will take out the garbage, they are forced to live with these vermin, an indignity of representative squalor from which they never seem to be freed, despite upwardly mobile Phyllis’ attempts to rise to apartments on higher floors.

The first flashback occurs when Martha is twelve, Carl is fourteen, and Phyllis is thirty-seven, in their first apartment away from their father after the divorce. Carl and Martha arrange the furniture and when they are finished, they swivel around Phyllis, reclining in an easy chair in Landau’s deft, humorous introduction of the women the play is allegedly about. Far from “taking it easy,” Lange’s Phyllis demonstrates she is “on edge” and seeks to quell her nerves at this first move without her husband. She immediately importunes her children for the following: her cigarette lighter (a gift from “the only one she loved”), a glass for the gin which she carries in a bottle in her large handbag, and ice, ready made in a tray in a box. After pouring herself a drink and puffing on her cigarette, she begins to relax and says, “Maybe mother will be able to get through this.”

Ironically, the “this” has profound, layered meaning not only for the moment, but for what is ahead for Phyllis, including single parenting, a possible nervous breakdown, poverty, responsibility as a mother, her job and more.

Phyllis pulls out their dinner in a McDonald’s bag from her bottomless black purse, which is empty of money because their father wiped out all the accounts. She speaks of their future-Martha cooking, cleaning and getting dinner, and Carl continuing his excellence of a near perfect score on the PSATs in verbal skills. Phyllis predicts Carl will be the first one in the family to get into college via a scholarship. Martha will take typing and get a job like her mother, so that if a man leaves her like her father discarded her mother, she will be able to support herself.

Though Carl quips flamboyantly about affording rent at the Algonquin, Martha sours at having to share a bedroom with her mother who snores. The favored one, Carl gets his own room. With their new beginning as latch key kids, who have to make their own lunches and deal with their own problems, toward the end of the segment, Carl humorously asks Martha if their childhood has ended.

Being a breadwinner and sole parent is a circumstance Phyllis bitterly resents. Culturally, moms still stayed at home, cooked, cleaned, did the laundry, took care of all the needs of the children, attended to them before and after school, and bowed to their husbands, who had the freedom to do what they pleased, expecting dinner at whatever hour they returned to a wife thrilled to see them. It is this “achievement” that Phyllis wishes for Martha, whom she hopes will marry someone unlike Mr. Herman, in other words a bland man who is unappealing to women and just wants a loyal wife like Martha will be because Phyllis has raised her to be the good woman.

Though Phyllis proudly proclaims this new apartment is a step in the right direction, Phyllis cannot “move on” to annihilate memories of her husband’s past physical and financial abuse, his scurrilous behavior, his machismo insisting all is his way. Filled with regret, Phyllis lapses into negative ruminations about their father who doesn’t provide child support or come to visit. Her cryptic remarks, sarcasm and “treatment” of Martha and Carl, who she openly praises and admires, while being “hard” on Martha, so she won’t marry a fraud, is sometimes humorous, but mostly unjust. In the telling Martha has our sympathy against this cruel, anti-nurturing mother.

Ultimately, we learn that each time they move for a reason that triggers them, each time they pack and unpack and arrange the furniture to settle in, they are still stuck in the same place emotionally because Phyllis can’t forget, forgive or release her anger. And though she adjusts as best she can, she relies emotionally on Carl and Martha, who she eventually evicts when she discovers they live a lifestyle that disgusts her and shatters her dreams for them.

Sprinkled throughout the five evictions and events leading up to them is Vogel’s humor and irony which saves the play from falling into droll repetitiveness because emotionally Phyllis’ needle is stuck in the same groove. Her emotionalism worsens as key revelations spill out about who she is as a woman, who once was adored by the same man who left her for “whores.” Throughout the sometimes humorous, sometimes tragic and upsetting events, Carl and Martha continue to serve and wait on Phyllis until they reach their tipping point. Overcoming these painful events with their mother because they have each other, Carl continues to guide and counsel Martha as a loving brother. This becomes all the more poignant when he leaves the family for various reasons, the last one being the most devastating for Martha and Phyllis.

Landau’s direction and vision for this family whose dysfunction is driven by internal soul damage shared and spread around is acutely realized. The following creatives enhance her vision: David Zinn’s scenic design of movable furniture, Shawn Duan’s projection design of interminable roach swarms, Jen Schriever’s ethereal, atmospheric lighting design (when Carl appears and disappears in Martha’s imagination), and Jill BC Du Boff’s sound design (I heard every word).