Category Archives: NYC Download

NYC Events

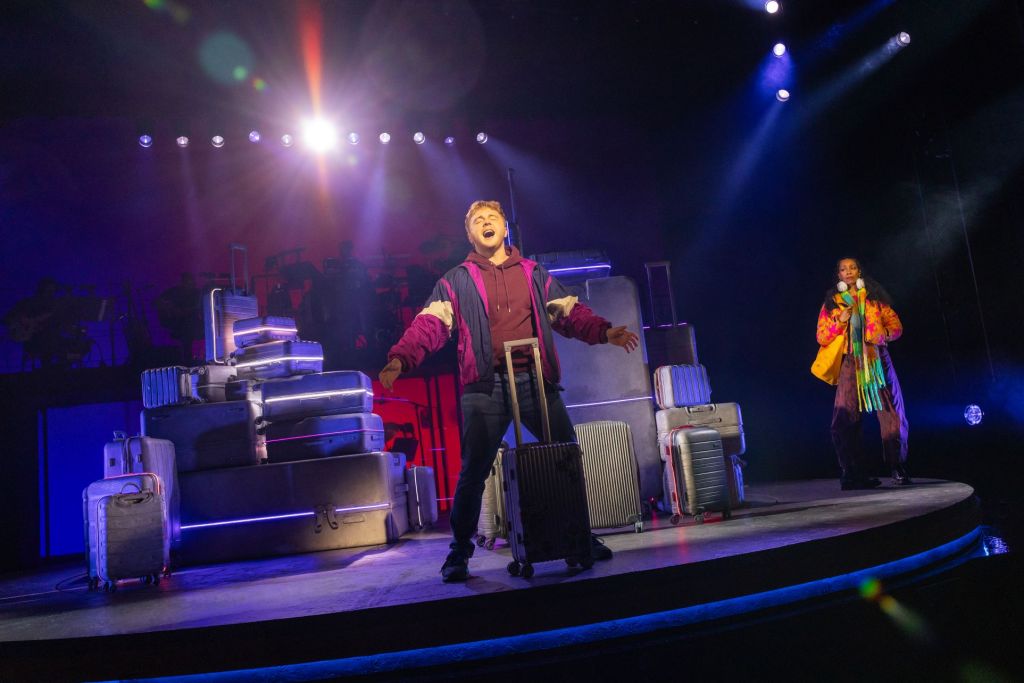

‘The Other Americans,’ John Leguizamo’s Brilliant Play Targeting the American Dream Extends Multiple Times

After a long career in every entertainment venue from films, to TV, to theater, Broadway, Off Broadway, etc., the prodigious work by the exceptional John Leguizamo speaks for itself. Now, Leguizamo tackles the longer theatrical form in writing The Other Americans, extended again until October 24th at the Public Theater.

Superbly directed by Ruben Santiago-Hudson, the theatrical elements of set design, lighting, costumes speak to the 1990s setting and cultural nuances. The following creatives developed a smart, stylish representation of the Castro household (Arnulfo Maldonado-set design, Kara Harmon-costumes, Justin Ellington-sound, Lorna Ventura-choreography).

Perhaps Leguizamo’s play could be tweaked to tighten the dialogue. All the more to have it shine with blinding, unforgettable truths sounding the alarm for immigrants in this nation. If tightened a bit, the complex, profound play would land perfectly as the unmistakable tragedy it inherently is. However, in its current iteration, Leguizamo gets the job done. The powerful play with comedic elements resonates to our inner core as a nation of immigrants and especially for Latinos.

Clearly, Leguizamo’s characterizations and themes add to the canon of classics that excoriate and expose the corrupted myth of the American Dream as a lie fitted to destroy anyone who believes it. That immigrants make the sacrifices they do to embrace it, is the ultimate tragedy.

Nelson Castro (played exquisitely by John Leguizamo), born in Jackson Heights from Columbian ancestry, embraces the American Dream. His wife Patti (the amazing Luna Laren Velez), from her Puerto Rican heritage, not so much. Patti’s values lead to loving her family and friends with devotion. Daughter, Toni (Rebecca Jimenez), who will marry the solid but nerdy Eddie (Bradley James Tejeda), looks to fit in as a white woman. The younger Nick (Trey Santiago-Hudson) was like his dad and took advantage of others, fiercely competitive. However, an incident changed him forever.

As the play unfolds, Leguizamo deals with the central question. To what extent have the warped values of the predominant culture negatively impacted this Latino family? From his first speech on we note that these twisted values have lured Nelson. The ethos-scam to get ahead-guides Nelson like a veritable North Star. He uses “getting over” as the key reason to provide for his family. This excuse rots everything under his power.

For example, Nelson acts the part of the upwardly mobile success story who always has a deal on the table ready to go. The irony is not lost on us when Nelson hypes a deal with a real estate big wig. Meanwhile, the mogul lives off his reputation for ripping off minorities. Sadly, Nelson admires the mogul’s pluck and con abilities. He ignores how this can potentially harms Latinos.

Mirroring the sick culture and society that values money and material prosperity over people, Leguizamo’s tragic hero tries to wheel and deal to get ahead. Making bad decisions, he overextends himself. Meanwhile, he encourages Nick and Toni to follow his lead. His overweening pride as the patriarch drives him to assume the mantle of a power player. Indeed, the opposite is true. During the process that causes him to fail and lie about it, he compromises his integrity and family’s probity and sanctity. That he willfully blinds himself to the consequences of his beliefs and suppresses his intelligence and good will to fit in, is the final heart breaker.

As in the classic tragic hero, Nelson’s pride also dupes him into a psychotic circularity to believe he has no recourse. Of course he believes the wheels have been set in motion against him by the society’s bigotry and discriminatory values. He should recognize and reject the society that uplifts such values because they support doing whatever necessitates getting ahead. The entire rapacious structure promotes financial terrorism and, whenever possible, it must be rejected. However, Nelson can’t reject it because he can’t help himself from being seduced. Instead, he persists in a prison of his own making, digging his family grave, on a collusion course of self-destruction.

Sadly, he internalizes the society’s inhumanity and makes it his own, a self-hating Latino. Because he adopts this construct because he loathes his immigrant self, he tries to create a new identity apart from his inferior ancestry. Thus, he moves to Forest Hills away from Jackson Heights where he lived “like an immigrant” in a place where cockroaches multiplied.

Finally, as we watch Nelson struggle to assert this new identity in a flawed, indecent, racially institutionalized culture (represented by Forest Hills and what a group of kids did to his son in high school), Leguizamo’s play asserts an important truth for immigrants. Internalizing and adopting the culture’s corrupt, sick, anti-human values is not worthy of immigrants’ sacrifices. This theme is at the heart of Leguizamo’s play. In his plot development and characterizations Leguizamo reveals his tragic hero chases after prosperity and upward mobility. The incalculable loss of what results-losing what it means to be human-isn’t worth it. If one does not weep for Leguizamo’s Nelson at the play’s conclusion, you weren’t paying attention.

To exemplify his themes, Leguizamo uses the scenario of the Castros, an American Latino family. They move from the homey, culturally diverse Jackson Heights to the white, Jewish upscale, racist enclave of Forest Hills. At the outset of the play Nelson, a laundromat owner, awaits his son’s return from a psychiatric facility. Patti has cooked up her son’s favorite dishes. Not only does this reveal her care and concern for her son, her comments to Nelson show her nostalgia for the Latin foods and people of their original Jackson Heights neighborhood in Queens.

By degrees Leguizamo reveals the mystery why Nick was in a facility. Additionally, the playwright brilliantly explores the conflicts at the heart of this family whose parents put their stake in their children, chiefly son Nick to get ahead financially in the Castro business. To recuperate, the doctors partially helped Nick with medication and therapies.

However, on his return home months later, he still suffers and has episodes. Patti sees the change in his dislike of his old favorite foods (symbolic). Not only does he reject meat, he rejects Catholicism and turns to Buddhism. Because a girl he met at the facility influences him, he moves away from his Latin roots. Later, we learn he loves and admires her and they plan to live together. However, he doesn’t look at the difficulties of this dream: no money, no family support.

The family conflicts explode when Nick attempts to be truthful with his parents. In his conversation with his mother we learn the horrific details of the beating he received in high school, why it happened, and how it led to episodes in college. Wanting to move beyond this through understanding, Nick learns in therapy that he must talk to his father. Nelson refuses to acknowledge what happened, and becomes a stalemate to Nick’s progress.

Additionally, his doctor supports Nick’s getting out from under the family’s living arrangements. Inspired, Nick yearns to create a life for himself away from their control to be his own person. Ironically, he follows in his father’s footsteps wanting to create a new identify for himself. Yet, he can’t create this identity unless he confronts the truth of what happened to him in high school and talks to his father. Unless he understands the extremely complex issues at the heart of his father’s tragedy, they won’t move forward together. Nelson must understand that he hates his own immigrant being and has embraced sick, twisted corrupt values which he never should have pushed on his family.

Meanwhile, in a fight with Nelson, Nick demonstrates what may really be happening to him. Though he survived the high school beating with a baseball bat, he most probably suffers from what doctors have come to understand as TBI (traumatic brain injury). With TBI the individual suffers debilities both physically and emotionally. When Nelson questions the efficacy of the treatment Nick received from doctors who didn’t really know what was happening to Nick, Nelson is on the right track. But the science had to catch up to Nelson’s observations.

Meanwhile, the problems relating to Nick needing the right help from his parents and his doctors, Nelson’s financial doom and the future of this Latino family under duress are answered in a devastating, powerful conclusion.

There is no spoiler. Leguizamo elegantly and shockingly reveals this family as a microcosm of the ills of our culture and society. Additionally, he sounds the warning for immigrants. If they don’t recognize and refuse the twisted folkways of the “American Dream,” they may lose their self-worth and humanity for a for a lie.

The Other Americans runs 2 hours 15 minutes including an intermission at The Publica Theater until November 23, 2025. https://publictheater.org/theotheramericans

‘Becky Nurse of Salem’ a Dark, Comedic Must-See at Lincoln Center

In Becky Nurse of Salem, Deirdre O’Connell (Tony, Obie, Outer Critics Circle award-winner for Dana H) is luminous. O’Connell portrays Becky Nurse, descendant of Rebecca Nurse who was convicted and hanged as a witch during the Salem witch trials. The actor, incisively shepherded by director Rebecca Taichman (Indecent) does a yeowoman’s job in a role that flies high in humor and crashes into tragedy and remorse at the two-act play’s heart-felt and satisfying conclusion.

Written by Sarah Ruhl (The Clean House, How to Transcend a Happy Marriage) the play artfully rides on a meme printed on protest signs during the global Women’s March of 2017, a march which took place the day after former President Donald Trump’s sparsely attended Inaugural celebration. Some of the signs read: “We are the Great, Great, Great Granddaughters of the Witches You Were Not Able to Burn.” Selecting the concept that women have transported themselves from that time to this and achieved prodigious exploits, then have been regressed by the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision and the Republican penchant for misogyny and repression of women’s rights, Ruhl’s play speaks to many issues with currency, vitality and humor.

Running at Lincoln Center Theater at the Mitzi E. Newhouse, the sardonic comedy investigates how the descendant of Rebecca Nurse has dealt with her haphazard life in Salem, Massachusetts, where she gives tours in the the Museum of Witchcraft, riding the coattails of her famous ancestor’s “cursed” reputation. On another level, Ruhl reveals that women still abandon each other and are abandoned by a culture surreptitiously steeped in patriarchal folkways, that suppress and stifle their growth professionally and individually. That rejection and judgment sets them up to pursue other ways to achieve what they want, some of them illegal and many of them ineffectual, causing them to plunge into a downward spiral, wasting their talents and intelligence.

Ruhl’s humor, under the clever direction of Taichman, develops into full blown belly laughs as Becky attempts to negotiate the ruins of her angst-ridden life, after telling off her new museum boss Shelby (Tina Benko). Her boss censures her for saying inappropriate epithets and getting carried away with what Shelby believes to be misinformation about “Gallow’s Hill.” Becky swears that the real place where Rebecca Nurse and the other women were hanged is on the spot of the second Dunkin’ Doughnuts farther away from the center of Salem. Shelby calls her down for spreading falsehoods, though clearly, as a non resident, she doesn’t have Becky’s information on the background of Salem.

Becky is the type of individual to be spunky, individualistic, strongly autonomous and not easily given to “obeying” someone she determines to be an inferior, despite her credentials. Though Becky apologizes, this isn’t enough for the arrogant Shelby who summarily fires her without hearing her pleas. It fits in with the plans for having the museum turn a profit without the overhead of salaries. Over ego and presumption, the competitive Shelby upends Becky’s financial security. The job has allowed Becky to support herself, pay her granddaughter Gail’s medical bills and generally get to the next day caring for herself and Gail. Shelby’s cruel firing leaves her with no recourse except to find another job in an area that has seen record unemployment. When Becky is cut out of the only job in town she is qualified for, Stan, who got the job, gives her the card of someone who can help her. She is a a witch.

Becky seeks the only safe place left open to her away from her own backward movement and regression. She goes to Stan’s recommended witch (the hysterical Candy Buckley whose twanging Boston accent is milked for well-placed laughs). Additionally, she also throws herself on the mercy of Bob (Bernard White), a high school sweetheart, now married, who owns a bar. She asks Bob for cash to pay the high-priced witch to end the Rebecca Nurse curse, and other expenses as the play unfolds with conflict upon conflict. Becky must reconcile her worsening problems or end up totally succumbing to the curse of her ancestor which appears to be directing her life toward complete failure and destitution.

Buckley’s Witch and O’Connell’s Becky make nefariously funny bosom buddies in changing the trajectory of Becky’s life since she can’t count on the culture to help her. Ruhl’s themes about women having to come up with ingenious ways to support themselves is clear in Becky’s reliance on witchcraft. The clever, randy spells that the Witch concocts for Becky prove to be effective on Bob who is entranced with his old sweetheart. Bob may be an answer to her financial problems, as men usually are for women who cannot sustain themselves due to a myriad of reasons, including unequal pay and unequal opportunities. The scene where Bob emerges in his underwear dancing to Donovan’s “Season of the Witch” as Becky joins him and they have a mild sexual romp is priceless. The scene, the choice of music is superbly directed by Taichman for maximum humorous effect. Both actors carry if off with authenticity and hysterical playfulness.

Unfortunately, when things appear to be going swimmingly for Becky with her new love and revenge on her former boss succeeding when she falls and breaks a limb, the worm turns. The universe which has been bent to the arc of the two women’s magical contrivances upends. During Bob’s love fest with Becky, he collapses and has a heart attack which places him in the hospital. There, Bob has a vision of the Virgin Mary who reminds him of his vows and his marriage and gives him an ultimatum if he wants to live. Thus, he must give up his adulterous relationship with Becky and sell his bar.

Meanwhile, Becky, convinced she can use the waxwork of Rebecca Nurse to conduct her own tours on the background of the real Salem witch trials freely goes off the museum’s canned script. She informs an interested group that The Crucible, Miller’s play is filled with inaccuracies. For example Abigail’s age in reality was 11 years old, but Miller, who fantasized about sleeping with Marilyn Monroe, made her older and lusting after John Proctor to satisfy his own fantasies about the celebrity. Becky insists that rather than it be a play about John Proctor’s “virtue” what really happened was 14 women were hanged, something that Miller didn’t portray accurately, nor did he care about. In one of the funniest lines in the play Becky says, “…our country’s whole understanding of the Salem witch trials is based on the feeling–of I want to fuck Marilyn Monroe, but I can’t fuck her.”

At that juncture, an officer interrupts her tour and arrests her because she has been charged with theft. She was caught on tape stealing the lifelike wax figure from the Museum of Witchcraft in order to fulfill the last part of her spell to achieve wholeness and to earn some money in her newly self-created job. But at the point of the arrest, there is a pivot in time magically. The setting regresses to 1692. A crowd (all who judge her in the present-Bob, Witch, Shelby, Gail, Stan) dressed in pilgrim outfits scream, “Lock her up!” Because she dares to question why she is being arrested, she transgresses the laws, an insult to the officer. Act I ends in the throes of her panic and fear as the crowd in pilgrim garb demands, “Lock her up. Kill the witch. Lock her up.”

As the complications arise and boil over by the end of Act I, we have watched the character of Becky become unraveled as she takes more pain pills and makes untenable decisions. Though she is obsessed with wanting to change her life, she has neither the means, the nature, nor the sobriety to find a path which will lead her to success. Everyone except the Witch has turned against her. They can offer no route out of the morass she’s built for herself in her Salem life. And to make matters worse, while she is in jail, Shelby ends up taking care of Gail and applying for custody of her granddaughter. It is both an emotional and psychic blow as Shelby now has the upper hand over every aspect of her life.

How Taichman and Ruhl bring Becky to her knees leading to the court trial where she raises herself up to admit responsibility and become accountable for her own actions is the crux of Act II. Vitally, Ruhl brings together thematic elements from 1692 with the present to magnify the issues Ruhl introduced in the beginning. Ruhl intimates that the threads of Becky’s self-destruction are rooted in paternalistic folkways which encourage women to accept victimization and passivity rather than to struggle and fight to empower themselves. Indeed, as Ruhl points out the through line from the 1700s puritanism to the present, such behaviors are culturally learned, generational patterns that are difficult to extricate oneself from. Even Shelby spouts the rhetoric that is most current as a “liberal” but is a hypocrite, incapable of employing the substance of what progressiveness is, women helping women. Instead, Shelby competes and follows what is most damaging to the town, its legacy and future. Her taking in Gail on the surface appears kind but is questionable.

Taichman’s and Ruhl’s vision combines the best of humor, drama and profoundly current concepts. To do this she relies on a superb ensemble with O’Connell, White and Buckley as standouts.

Kudos to the creative team who conveys the settings and provides the chills that leak from the past to the present and back again. Particularly effective are the projections of the black birds symbolizing the occult and perhaps evil spirits at salient points in the play. These are effective thanks to Barbara Samuels lighting and Tal Yarden’s projections. The sets are effectively fluid and mimalistic thanks to Riccardo Hernandez. The costumes designed by Emily Rebholz are eerie enough to remind us of the fearful pilgrims.The waxwork of Rebecca Nurse is sufficiently life-like to imagine her presence being enlivened for a twinkling moment, then vanishing as all things magical are wont to do.

Because of Taichman’s direction, the production translates into masterful performances with high energy, LOL humor and current themes without relying on rhetoric or cant. This is not easy. Taichman, Ruhl, the actors and creative team make this comedic play a must-see. For tickets and times go to their website: https://www.lct.org/shows/becky-nurse-salem/

‘Triangle of Sadness,’ NYFF60, Östlund’s Brilliant Satire

The outrageous, mind-bending Ruben Östlund (Force Majeure and The Square) presents an informal treatise on power constructs in his immensely sardonic, over-the-top Triangle of Sadness. Deftly, Östlund presents an interesting sequence, holds our attention, then gyrates away on another tangent. Tension, shock and awkwardness, that comes from uncertainty and being whipped off-balance, characterizes this filmmakers’ modus operandi. Profoundly, our state of unease, uncertainty and laughter keeps us entertained on his playground of Triangle of Sadness.

The film provides an extraordinary and macabre fun house where no rules apply. Indeed, reversals turn on a dime. Also, mythic themes pop up and unravel our complacency. Östlund enjoys having his audience on. Invariably, his situations and characters, profoundly stained, cause us to feast on our own hypocrisy while projecting our foibles onto his characters. As a result we laugh heartily at the wild ride he makes us take. With mischievousness Östlund proves that all human nature has at its core the same rotted substance. Regardless of how elite the class, how gorgeous the outer shell, how “in control” and staid people appear to be, they, and humanity are one crooked mess that drown in their own s**t. (This is a marvelous metaphor that Ostlund slams us with in the middle of the film.)

The title references a physical imperfection-the cosmetic industry term “triangle of sadness.” Alluding to the wrinkles between the eyebrows, these imperfections eventually need Botox for a smoother appearance. Humorously, Östlund strikes us with the phrase during the opening sequence of the film. Relating it to the important theme of physical perfection and the sanctity of beauty, that triangle metaphorically haunts the characters throughout the film. In every sequence wrinkles eventually appear on the surface of the once perfect situation. Afterward, problems, storms, trauma and insidiously terrible events rain down.

As usual Östlund begins his film with energy. Backstage at a casting call, we note a documentary crew. Barking orders and questions, assistants interview gorgeous, camera-beautiful men about their career choices in a profession that pays women models much more. Put through their paces the hunky models alternate their facial expressions. First, assistants tell them to think H & M Ad: boyish grin, fun-loving, happy. Then assistants tell them to change their expression for the upscale brand image like Dolce & Gabbana. The hotties change their facial expressions to a remote and solemn stare. At some point during the models rapidly alternating expressions, the assistant mentions their “triangle of sadness.”

Thus, in this hysterical sequence the filmmaker exposes the elitism built into the culture through subliminal images that promote brands. Rich equals remote and unflappable. And middle class equals accessible, friendly, economical. When we wear the upscale brands, and manifest the serious look, we don wealth. The filmmaker ridicules this canard, the foundation of corporations’ overpricing and profiteering.

Immediately, the filmmaker preps us for a subtle expose of the themes of wealth, privilege, beauty, as he pits them against the middle class struggle to gain the enviable elites’ “heavenly” status and position by any means necessary. Meanwhile, the concepts of worth and value of life, decency, generosity, wholeness, kindness fly out the window. The “Eternal Verities” of ancient times, in other words, the moral and human values brought by insight, meditation and reflection don’t show their expressions when money, power, privilege hold sway. The various players in the cruise portion of the film are pawns of corporate commercialism and conspiring victims of their own demise.

After the humiliating casting call the writer/director highlights his protagonist Carl (Harris Dickinson) who we just watched embarrass himself. Sitting in a luxury restaurant, he looks upscale with his female physical equal, the lovely Yaya (Charlbi Dean). The opening shot of this perfect couple shines with the superiority of great genes and the discipline to maintain and enhance them.

Ironically, Östlund presents that beauty equals wealth and status. And gorgeousness opens the doors to privilege. However, once Carl and Yaya open their mouths, another hysterical truth emerges. If pretty is surface, ungraciousness goes clear to the bone, hinting at soul ugliness.

As the couple nit picks about who should pay the check employing gender stereotypes and power constructs, the clever dialogue hits the mark. Though Yaya earns more than Carl, an ironic reversal, their bickering shows their physical perfection only delivers money to Yaya. As such the filmmaker uses the occasion of Yaya making more than Carl as a gender power dig. Though she offered to pay the day before, she changed her mind because the alpha male should pay.

Thus, the wrinkle appears. Destroying the image of their picture perfect looks and happiness we saw at the top of the scene, they quarrel. With incredibly clever and funny dialogue, Östlund introduces the themes that will abide throughout. Additionally, in the scene and throughout the film, he strips bare cultural male insecurities, fake etiquette, the destructiveness of ancient folkways and much more.

With a striking jump cut, we arrive with the stunning Carl and Yaya on a luxury cruise. Perhaps their looks have served a monetary reward after all. Interestingly, they’ve been invited to enhance the landscape of the cruise to go along with the other elite classy appointments. Also, Yaya an influencer got the cruise as a free perk, a lucky benefit. How this turns out defies one’s imagination beyond definitions of wild and crazy.

As they converse with a senior set of passenger couples, they hang with a Russian fertilizer oligarch, an arms manufacturer an oil baron, etc. Dimitry (Zlatko Burić gives a LOL performance) introduces himself with the phrase, “I sell s$it. After a huge pause, he clarifies, “fertilizer.” Occasionally, we note shots of the crew who makes the ship sparkle and satisfies the passengers every whim. Even Carl’s insecurity takes precedence when he complains a crew member leers at Yaya. Summarily, the captain’s first mate fires him. Indeed, a speedy launch comes a few hours later to remove him. Yes, these rich and beautiful rule the little people, the microcosm of the larger macrocosm of global reality, Östlund, suggests. But remember, the wrinkles.

Passenger requests land from extreme to extreme. In fact Dimitry’s partner suggests the crew take a break in a mawkish attempt at being egalitarian. Of course, they do, for a bit, leaving no one at the helm of the ocean-going yacht. When the Captain (a winningly negligent and drunk Woody Harrelson) refuses to join them for the break, we note another wrinkle. The smooth surface of the ocean can turn on his orders which suffer delays as he puts off his assistants. Finally, one nails him down with a momentous decision. When will they have the meet-up with the passengers at the Captain’s Dinner?

By the time viewers reach the final act of the immersive, volatile and innately entertaining Triangle Of Sadness, which lands them on a desert island with a small group of shipwreck survivors, they will have sworn that its beginning, set in beauty-obsessed corners of the fashion world, happened a few movies ago. This is the heartiest possible compliment I can give Swedish auteur Ruben Östlund’s latest brainy satire, a continually self-renewing yet uncompromisingly coherent opus. It’s reminiscent of a rich and compact trip you might find yourself on in a country you haven’t visited before, with every new experience feeling just as welcome, rewarding and surprising as the last.

To tell more would ruin the Buñuelian twists of this poison-dipped farce on class and economic disparity, which doesn’t skewer contemporary culture so much as dunk it in raw sewage. A NEON release opening in theaters November 29th.

Roma Torre Interviews Tony Award-Winning Producer Pat Addiss

LPTW Invites the Public to the Oral History Interview of Pat Addiss

On 17th of October at 6 p.m. in a joint collaboration of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts and League of Professional Theatre Women (LPTW), Roma Torre, renowned theatre critic will be interviewing Broadway and Off-Broadway Award Winning Producer Pat Addiss. One award winner questions another award winner, a fitting highlight of LPTW’s celebration of its 40th anniversary, supporting women in the arts through networking, award grants, educational programs and much more.

Torre and Addiss, both women of pluck, drive and industry sport resumes that testify to their love of the theatre and prodigious efforts supporting New York Theatre and thus American Theatre. Addiss, a long-time member of LPTW, has produced more than 20 plays on and off Broadway. Many of these have won or were nominated for a Tony, notably: Little Women; Chita Rivera: The Dancer’s Life; Bridge and Tunnel; Spring Awakening; 39 Steps; Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike; and Eclipsed.

Addiss has a keen intellect for understanding what appeals to audiences. When she produces a show, she dedicates herself to making sure the actors (who love her), feel supported and appreciated. I have reviewed a number of her productions after I met Pat out in the Hamptons when I was covering the Hamptons International Film Festival. I have seen her productions (Little Women, Bridge and Tunnel, 39 Steps, Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike), and adored them even before I was introduced to her by her close friend Magda Katz, also on assignment at the HIFF, and became friendly with Pat and Magda.

Pat’s Off Broadway productions are equally stellar. Buyer and Cellar is a classic that starred Michael Urie here and in London. To raise funds for Equity Fights Aides during the pandemic, Michael Urie streamed a live, amazing performance of Buyer and Cellar from his apartment. Urie did a phenomenal job with the help of technicians upstate, all of which was perfectly COVID compliant. It was an inspiration and uplift during the dark times of the COVID quarantine.

Pat’s Off Broadway musical, Desperate Measures, won 2 Drama Desk Awards, an Outer Critics Circle Award, and receives raves everywhere it plays in the USA,” Ludovica Villar-Hauser, LPTW Co-President and Producer of this event, noted. A musical satire of Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure with a “wild west” conceptualization, Desperate Measure is another production classic that shines.

Interviewer Roma Torre needs no introduction to faithful viewers of NY1, who happily watched Torre for 28 years as the channel’s midday anchor and chief theatre critic. What viewers might not know is that Torre is a recipient of three Emmys and more than 30 other broadcasting awards. Torre has reviewed more than 3,000 Broadway and Off-Broadway productions and has been inducted into the National Academy of Arts and Sciences Silver Circle, honoring her for lifetime achievement in newscasting.

This event honoring Pat Addiss, part of the 40th anniversary celebration of LPTW, is open to the public. The event is being held at the Lincoln Center Library of the Performing Arts on 40 Lincoln Center Plaza on Amsterdam Avenue in New York City. It is part of a series sponsored by the LPTW Oral History Interview Project in partnership with the Library. To view past Oral History interviews, visit the Library’s Theatre on Film and Tape Archive, or visit LPTW’s archive.

The Pat Addiss interview by Roma Torre is one of the “exciting in-person and online events, where we will honor significant contributions of theatre women across all disciplines, who represent a broad array of ethnic, cultural, and racial backgrounds. Most of our programs this 40th Anniversary Season for LPTW will celebrate our incredible Membership,” said Villar-Hauser.

Women working in the theatre industry are eligible to join LPTW. For more information on upcoming events and to join LPTW, visit: www.theatrewomen.org.

‘The Daughter-in-Law,’ by D.H. Lawrence is Superb! Theater Review

D.H. Lawrence is rarely known for his plays. However, British critics have noted that he was a master playwright, and if discovered as such earlier in his life, he would have been appreciated for his dramas, however maverick and forward-thinking. One such incredibly rich play is being presented by the always excellent Mint Theater Company, who enjoys bringing to life rare jewels in drama that have often been overlooked. The Daughter-in-Law is one of these gems.

Directed by Martin Platt The Daughter in Law presents an amazing portrait of an independent woman, Minnie (Amy Blackman), a former governess married to a collier (coal miner), Luther Gascoyne (Tom Coiner). The couple live in a mining town near his mother’s (Mrs.Gascoyne-Sandra Shipley) home where his brother Joe (Ciaran Bowling), also a collier, works with him in East Midlands England.

The setting is autobiographical and akin to where D.H. Lawrence’s father worked and where he and his siblings lived with their mother (reminiscent of Minnie), who had cultural aspirations for Lawrence, and who inspired him in his studies. Lawrence’s play evolves into conflicts among the characters. These are rich in thematic evolution that comes to some resolution by the end of the play after the colliers riot against scab workers during a strike. Interestingly, the themes involve gender roles, class, economic inequity and familial love. Also, Freudian tropes between mothers and sons, an issue that Lawrence often investigated, receives a hearing in this realistic and beautifully acted production that Platt has tautly directed, so it remains provocatively, emotionally, tense throughout.

To a fault, the actors have been schooled in the Midlands accent which provides realism and creates the audiences’ attentive stir to understand all that the characters communicate. At times, this takes getting used to. However, the actors portray the characters’ emotional feeling sincerely and authentically, so that one understands, even though one may not be able to translate word for word what the characters say.

Nevertheless, when Joe (the vibrant Ciaran Bowling), enters sporting an arm in a sling and his mom (the dynamic and authentic Sandra Shipley), fusses over him with his dinner and probes what happened with receiving a disability check, we understand their close relationship, and we also understand that mother and son mutually care for each other, living under the same roof, watching out for each other, while other family have gone on to make their own lives.

The hard conditions of the mines remind us of the corporate structure which Lawrence reveals has changed little over one hundred years later. The owners receive all the benefits, and the workers are given low wages and are subcontracted out to keep them hungry and off-balance, so they are unsure of where they stand in the company’s graces. Joe and his brother, like their father before them, were at the mercy of the owners; and their father died as a result of an accident we find out later in the play. This undercurrent of workers vs. owners is the driving undercurrent and reveals that the misery of need and want is what impacts the families who live and depend on coal mining for their survival.

During lively dinner conversation, Joe tells his mother that his attempt to receive a check for his broken arm has been rejected. His manager tells his version of “the acceptable truth” of what happened to Joe, so that it is Joe’s fault that he was injured, because he was “fooling around.” It was not that he was injured on the job because of some dereliction of another worker or the mine. Lawrence strikes at the inequality of the haves and have nots and the managers who make sure to protect their employers. Thus, we feel for Joe and his mother, who are not destitute, but who struggle economically. If any stress comes to either of them, they are a few steps away from the equivalent of the poorhouse. Such is their economic and class level.

Into the background of this economic insecurity and potential working class impoverishment comes Mrs. Purdy (the convincing and excellent Polly McKie), a neighbor who brings disturbing news. Her daughter, who she describes as rather a simple girl, is pregnant. And after avoiding the direct truth until Mrs. Gascoyne drags it out of her, Mrs. Purdy lays the blame at the feet of Luther, who married Minnie seven weeks before. Mrs. Gascoyne pushes Mrs. Purdy cleverly off on Luther and Minnie, especially Minnie since she has brought some money into the marriage and can afford to pay Mrs. Purdy and her daughter off for their silence and for Bertha’s upkeep with the baby. This suggestion is made after Joe and Mrs. Purdy verify that Luther was seeing Bertha Purdy, something that Mrs. Gascoyne didn’t realize because Luther kept it under the radar and wasn’t serious with her.

Assurances are made to Mrs. Purdy that she must see Luther and Minnie at their house, since Minnie has received an inheritance that Mrs. Gascoyne insists should be used to pay off Mrs. Purdy. This malevolent and resentful suggestion is disputed by Joe whose empathy for his brother and Minnie is greater than his mother’s. As Mrs. Gascoyne discusses Luther’s marriage to Minnie in demeaning terms, it is obvious that she resents the “high and mighty” Minnie ending up with her son. She tells Mrs. Purdy that it’s because he is the only one she could get.

At this point not meeting Minnie, we wonder who this snotty woman is and side with Mrs. Gascoyne because we have gotten to know this nurturing, motherly type who obviously cares about her children. Based on Lawrence’s brilliant dialogue characterizing Minnie through the eyes of Mrs. Gascoyne, we believe that this snobby woman who thinks she’s “better” than the colliers and their families is pretentious. Also, we believe that she is so desperate, she doesn’t love Luther, but she just wants not to be an old maid.

Interestingly, Lawrence allows this portrait of Minnie to remain, until we see her relationship with the two brothers unfold. Gradually, her characterization is revealed and her strength, power, indomitable wisdom and love for Luther becomes apparent but with twists and turns, ups and downs by the the end of the play. But first, she must stand up and upend her mother-in-law’s presumptive discriminatory attitude against her, and then wait for the right moment to forgive her so that the two of them become closer.

Platt’s direction in keeping us wondering how Minnie will react when she discovers Luther has a child on the way is subtle and yet eventful, as Lawrence provides surprises and unusual events which keep us enthralled. Mrs. Purdy tells Luther about the child, but Joe manages to drive Minnie out of the house so that she leaves before Mrs. Purdy confronts her with the “truth.”

In an ironic twist it is Luther, who returns much later drunk, guilty and ready to be rejected. He picks a terrible fight with Minnie, then in humiliation covered over with bravado, he reveals that he has gotten Bertha with child. Interestingly, Minnie remains calm and collected, non judgmental and rational, presenting the idea that the child may not be Luther’s, but another man’s. Nevertheless, Luther becomes churlish and obnoxious, which prompts her to call him out for his meanness, especially when he suggests that Bertha was nicer to him than Minnie.

The actors do an exceptional job in raising the stakes and increasing the argument and tension between Minnie and Luther, so that we don’t know whether or not they will break up, Minnie will leave, whether Luther will have to return to his mother or both of them will end up bloodied and bruised as they come to blows. In Lawrence’s characterizations of Minnie and Luther, their relationship becomes explosive and we aren’t sure whether it’s because of class differences, economic differences (she came from a bit more money than he and he may resent it) gender role assumptions (Minnie has worked for herself and made her own money) or something else. Interestingly, we don’t consider that they may love one another, feel hurt and pain that they might lose each other, or are emotionally trying to settle out their own feelings.

The actors are just exceptional in revealing this marvelous nuance and the director has shepherded them so that we are off balance in attempting to figure out how they really feel about each other. One of the high points of the play comes when Minnie confronts her mother-in-law and indicates that she has not allowed either of her sons to become men. Minnie points out that she has babied them so that they remain shells and are forced to rely on her emotionally and psychically which has destroyed them and made them weak. Interestingly, Joe agrees with Minnie. And he indicates this situation emotionally has debilitated him and at times has left him suicidal. Ciaran Bowling, Sandra Shipley and Amy Blackman are wonderful in this confrontation scene.

Amy Blackman as Minnie gives an amazing and powerful performance. She is stalwart and strong as she stands up to Sandra Shipley’s mother-in-law who manages to be infuriating and yet very human and poignant as a woman who is needy and relies on the ties amongst her and her sons. Tom Coiner as Luther is frightening and brutal as well as weak and sheep-like when he finally admits his love and dependence on Minnie.

Lawrence concludes the play surprisingly by revealing what has been at stake all along. It is a complicated and intricate conundrum that he presents and then the revelation clearly indicates that there was no mystery. This is how a couple is settling into themselves and separating from every other family member to cling to each other as they define themselves in the most important relationship of their lives.

This wonderful production should be seen for many reasons, principally because D.H. Lawrence has written a great play with nuanced characters in striking relationships that are unfamiliar to us that the Mint Theater Company has presented in this superb revival. The intricate details of setting, the props, the coal stove that is the hearth, the set design, down to the food and plates that show Minnie’s aspirations to being middle class, manifest a reality that makes us identify with these individuals. Kudos to the tremendous effort on the part of Bill Clarke (sets), Holly Poe Durbin (costumes), Joshua Larrinaga-Yocom (props), Jeff Nellis (lights), Original Music & Sound (Lindsay Jones).

The Daughter-in-Law comes in at two and one-half hours and is at New York City Center, Stage II. For tickets and times go to their website: https://www.nycitycenter.org/pdps/2021-2022/the-daughter-in-law/

‘Prayer for the French Republic,’ Haunting, Current, Universal

Shifting in flashback between (2016-2017) and (1944-1946) set in two different Parisian apartments, Prayer for the French Republic (currently at Manhattan Theatre Club) by Joshua Harmon (Bad Jews), directed by David Cromer (The Band’s Visit), focuses on a Jewish family’s concerns about identity, safety and security in a country that they’ve called home for five generations. The backdrop of their apprehensions then and now is an uncertain world where humanity’s fears and needs turn increasingly predatorial. Capitalizing on such fears, political actors mine the unbalanced, raw emotions of deranged citizens, to create scapegoats which help grow their power and popularity. Whether left or right politically, oftentimes the scapegoats are religiously or ethnically engineered.

Such was the case in France during Hitler’s fascist occupation and the Vichy government’s cooperation with the roundup of French Jews that were murdered or sent off to concentration camps. Such is the case in France in recent years where attacks against Jewish citizens have multiplied, stirred up by opportunistic, right-wing, fascistic politicos ravenous for power.

As an overseer, Patrick Salomon (Richard Topol), connects the ancestral ghosts from the past, his great grand parents, Irma and Adolph Salomon, grandfather Lucien and his father Pierre, still living, as a bridge from the past to the present. In the present are Patrick, his sister Marcelle Salomon Benhamon, husband Charles and their adult children, Daniel and Elodie. The play is Patrick’s meditation on five generations of family. Patrick redefines what being a Jew in France means, as he narrates the saga of their Parisian Jewish identity and magnifies it in light of the age-old conundrum Jews historically confront throughout the ages. To survive do they assimilate, or do they risk the danger of standing apart as they embrace their religious beliefs?

As the play progresses, these questions expand and complicate against the current global crises (climate, socio-political, economic). What do Jews do in response to severe persecution? Do they embrace their identity, suffer and die valiantly resisting? In the name of living do they become invisible, marry out of their religion to avoid the turmoil, danger and abuse that comes with the trajectory of uncertain social unrest that Jews inevitably find themselves in the midst of? Do they emigrate to “certain” safety?

Interestingly, before the last generation of the Salomon family makes any final decisions, they confront their father Pierre and present him with their conundrum. Would he go with them, for example, to a safer place with other Jews in Israel? Who better than their father, a survivor of the atrocities of Auschwitz, can ,advise them about their future? Indeed, he made his decision years ago, married a Christian woman and didn’t keep up Jewish tradition, intentionally. He remained safely in Paris raising Marcelle and Patrick without keeping ancient Jewish traditions. And until Marcelle married an Algerian Jewish emigre, they didn’t keep them either.

Patrick (the superb Richard, Topol whose easy, relaxed persona is confidently relatable and empathetic), introduces the Salomon family to the audience and discusses their business operating a store where they attempt to sell beautiful pianos that are no longer viable in modern society. Patrick brings us into 2016 to view his closest relatives, sister Marcelle (Betsy Aidem), brother-in-law, Charles (Jeff Seymour), their bi-polar daughter Elodie (Francis Benhamou), and son Daniel (Yair Ben-Dor). The cross-section of their lives begins as Marcelle (Betsy Aidem in a fine, layered performance), becomes acquainted with her guest, Molly (the clear-eyed, authentic Molly Ranson), a non-practicing Jewish, distant cousin from NYC.

Their humorous exchange ends when Daniel comes in bleeding and an uproar begins in the household. He has been attacked in a hate crime where the young men who assaulted him yell out epithets because he has obviously distinguished his religious identity with a kippah. The arguments ensue and we discover that neither Marcelle nor Charles make an obvious show of their Judaism and that Daniel is the only Orthodox one in the family. Molly watches the scene unfold and learns as we do about family dynamics.

Daniel recently became Orthodox. He doesn’t even want to go to the police to identify his beating as a hate crime. Though Marcelle insists, Daniel makes excuses that he didn’t see his attackers and the police won’t do anything about it. All land on the fact that it will only exacerbate matters in the society and spread more fear. The discussion is closed when Daniel insists Marcelle light Shabbat candles.

The scene deftly shits to the past, as we note that ancestry (the ghosts of time past), runs concurrently and influences the Salomons in the present. The spirits of their forebears come to life, and we watch the characters in their small Parisian apartment in 1944, having a conversation about their children and other family who escaped France rather than stay, which other family did. As Irma (Nancy Robinette), and Adolphe (Kenneth Tigar), wait safely in their apartment, away from the horrific persecution of Jews throughout the Third Reich occupied countries, of which France is one, they pray that Lucien and Young Pierre are safe in the mountains. This is what Adolphe encourages Irma to believe. As they pray that Lucien and Pierre will come home to their apartment in Paris, hope sustains them.

Patrick connects present and past during these moments. He ruminates about what his great grandparents, grandparents and father went through, touching upon the conversations they may have had and the rationing they went through. Furthermore, he reveals the family’s penchant for argument and debate before decisions are made. Adolphe humorously suggests that at the reunion when family is together, after ten minutes of peace there will be arguing and fighting and crying. We marvel that Irma and Adolphe can sit there and imagine what it will be like after liberation. We discover later that most of the family who didn’t escape to Cuba or elsewhere died. Adolphe’s fantasy is a manifestation of hope to uplift Irma. Their safety in Paris affords them this luxury of hope; meanwhile, Jews died in the millions.

How are they alive? Patrick relates that the superintendent of the building didn’t give Adolphe and Irma up to the Gestapo during a roundup. Thus, both escaped in that rarest of occasions; they were protected by other French people. However, at this point, they don’t know the fate of their son Lucien (Ari Brand) and their grandson Pierre (Peyton Lusk) who may have fallen into the hands of the Nazis and ended up gassed in a concentration camp. But Adolphe and Irma live in faith securely, waiting their return.

In the segue back to the present Molly and Daniel form an attachment. Daniel explains why he has become Orthodox when the family never was. He discusses the attacks at the newspaper Charlie Hebdo and the killing of four Jews at the Kosher Supermarket in Paris as proof that the hate crimes against Jews are increasing. On a hopeful note, he tells Molly that the peace marches against the violent attacks were massive, and Prime Minister Manuel Valls stood with the Jews against Benjamin Netanyahu, who told them to leave France and come to Israel. Valls encouraged belief in the French Republic stating, “If 100,000 Jews left, there would be no more France; the Republic of France would be a failure. Daniel points out that Jews left, but only a tiny fraction; the rest stayed. He affirms that always it is a matter of choice. Jews stay in France because they love their nation and have faith in the French people.

It is this concept of choice that carries through the rest of the play in the decision whether to escape persecution and hate crimes or stay and fight with courage and resistance. But slowly, this family because of the past losses, attenuates their faith in the French Republic.

First, it is Charles who rebels against staying in France after we hear the prayer for the French Republic spoken in a voice over in French and English when Charles and Daniel go to the synagogue. The Jews loyally support the French Republic, though some, like Charles, feel it is a waste of time. As father and son walk home, Charles notices the stares of disdain and anger at Daniel’s assertion of his religion. Charles insists, “I can’t take it any more.”

Once again the family is up in arms presenting arguments. Marcelle refuses to leave, decrying the beauty of their life in France. Fed up Charles wants to go to Israel. He remembers the persecution he experienced in Algeria where everyone got along when he was a child, but later socio-political forces disrupted the social fabric. Indeed, he has no allegiance to France. He doesn’t have the history, as Patrick puts it, that Jews have been in France for over 1000 years and have made a way for themselves there.

The discussion and wrangling back and forth between Aidem’s Marcelle and Jeff Seymour’s Charles is powerful and strident. We are riveted by the danger in Charles’ tone, of hidden subtext that is palpable and his fervor to believe there is safety in Israel, though that isn’t necessarily a rational conclusion because of the terrorism there as well.

The argument carries over when Molly and Elodie go to a Dive Bar. Francis Benhamou’s Elodie rant against Molly Ranson’s Molly is humorous and as powerfully strident as Charles’ argument with Marcelle. Elodie gives forth, illustrating Molly’s hypocrisy when she argues against Israel’s Palestinian settlements. Elodie’s point drives deeper to human nature. There are the power-hungry and the occupiers; how does one resist not becoming power-hungry as a matter of security? Molly’s criticism belies historic U.S. colonization and oppression of everyone but white males. Elodie indicates that finger pointing is useless.

Eventually, both manage to reach common ground on a personal, familial level. Humanity takes precedence in their discussion when Elodie explains that Daniel became Orthodox because of a girl. Revelation of his vulnerability opens the door to Molly’s and Daniel’s relationship. It also opens the door to Marcelle’s fury because she believes that Molly has taken advantage of her son’s vulnerability.

Nothing is resolved even after Charles and Daniel return from a trip to Israel to look at living arrangements and social culture. Charles gives in; he affirms wherever Marcelle is, he will stay with her. Daniel proclaims that he didn’t want to go to Israel, but just accompanied his distraught father to help him. The playwright indicates the confusion and the stress that accompanies the hassle of confronting danger in one’s daily life, as this family feels they are under siege since Daniel paraded his Jewishness. But it is understandable because the family has a history of loss and death at the hands of French fascism. Furthermore, fascists like Marine Le Pen (Deputy of the French National Assembly), and her right-wing conservative political group don’t readily disavow fascism.

As the scene shifts to the past, Lucien and Young Pierre return from the camps bringing the horrific information that family was lost. Lucien is overcome in the telling of it. Ari Brand’s performance is appropriately drained, inwardly devastated but holding it together as best he can. It is Young Pierre who eventually expresses how his father’s hope saved him. Peyton Lusk gives an incredible portrayal of the PTSD of a young person returning from an unspeakable experience. But as Lusk explains how he survived, once again comes the affirmation that hope is how people survived the persecution, attacks and killing, as community and family helped family. For Lucien always told Young Pierre that they would make it.

But it is in the final act when the dam bursts with a traumatic episode for Marcelle, who by degrees has given up on her beloved Paris. It occurs at the symbolic Passover Seder, a remembrance of when God wrought miracles to help the Israelites escape slavery in Egypt. At the celebration, when they arrive at the “opening of the door to let the angel in,” Marcelle becomes hysterical like Charles did weeks before. She, too, has a “can’t take it any more” moment and refuses to open the door, terrorized that a Marine Le Pen engineered terrorist will enter and kill them.

The scene is shocking. Betsy Aidem’s performance is riveting as are the other actors. Harmon establishes centuries old horror of death at the hands of haters. Though the idea seems ridiculous, recently a woman was burned alive in her apartment in Paris.

That Harmon has conjoined Marcelle’s terror with the symbolic traditional night commemorating their escape from persecution and oppression is an apotheosis. In an irony of twisted emotion, Marcelle gives in to the terrorists who want Jews gone from “their” country, the most grievous insult of all. It is an incredible message because Marcelle’s fear destroys her ability to believe in God’s protection, a basic fact of her religion. She believes in God’s protection only if she flees, like the Jews of ancient history. The hatred of others intellectually and representationally in various select acts of violence has overwhelmed Marcelle’s ability to feel secure in her own religion, her own apartment, her own country, her own identity. She must leave.

Of course it is a sardonic fact that her family’s escape will be to one of the most dangerous countries on the planet. Patrick raises the issue about the security question in Israel. Indeed, physical security must have as its precursor intellectual and philosophical security in the Golden Rule of “do unto others,” democratic values, an ideal that France attempts to follow and does with exceptions, better than other countries. Certainly, in Israel’s West Bank, the Golden Rule does not abide for Palestinians who are treated as “the other” and are oppressed and have no rights under Netanyahu’s ultra right wing, increasingly anti-democratic government.

Harmon’s play is filled with thesis/antithesis arguments, and this is a family that generationally loves a worthy argument with well supported logic and details. Patrick takes the position that the Republic of France will stand by its ideals and that there is nowhere safe globally, moment to moment; not Israel, not the United States, not Europe, the Middle East, Asia, etc. Human hearts are not safe.

To counter his sister he correctly asserts that the fascistic government of Marine Le Pen will be voted down and the Republic will persist. Harmon’s point is well taken. There are those across the globe who value equanimity in greater numbers than those whose megalomania and craven hate seeks the death of others for power. However, his commentary falls on deaf hears; Marcelle has made up her mind to go to Israel where their Jewish identity may be expressed freely with little fear of reprisal by crazies. For her France has nullified her existence as a Jew.

Whether she will feel safe in Israel relies on hope and sacrifice. In Israel they have to start all over again. They will have sacrificed their careers, friends, culture, language, everything for the hope of a safety and security that is never guaranteed. If they are on a bus that terrorists decide to blow up in Tel Aviv, there is no way to stop that. But Marcelle is convinced, turning 180 degrees from her position at the play’s beginning. Fear possesses her soul and she makes decisions based on it.

In the final segment of the play the argument takes further flight with elderly father Pierre (Pierre Epstein is eloquent in this last speech to the family). If they leave, it is their choice, but he will not go with them. Having the freedom to choose and not be compelled is vital to his identity. Ironically, by giving into their fear, they have compelled and oppressed themselves. Pierre who has seen the worst of the camps and survived, knows the difference of experiencing the worst. His children and grandchildren have not and they don’t want to. That is why Marcelle compels them to leave, though such an event happening again is a probability off the charts. But no one dares speak that to her, not even her own brother.

The performances are sterling and sensitive, at times funny, and always compelling. The canny direction by Cromer to “get it all down” and thrill the audience with ideas and concepts is just great. I particularly enjoyed the Set Design by Takeshi Kata that designated the differences between present and past efficiently and seamlessly. The Lighting Design by Amith Chandrashaker provided the ephemeral, soft, wistful tone of the past and stark contrast with bright light that magnifies the present. Kudos to the other creatives, Sound Design by Lee Kinney & Daniel Kluger, Original Music by Daniel Kluger.

Prayer for the French Republic is revelatory and insightful in questioning our arrogance to believe we, who are transient beings on this planet, have an identity and home, knowing mortality comes to all of us physically. He also twits our assumptions about safety and security, the difference between life’s enjoyments and living an existence permeated by psychological fear. Above all he designates in a Republic, there is the right to choose one’s destiny, free from personal harm because, if applied, the rule of law secures it. But if it is not exercised, then what? Harmon asks the questions through lives, relationships and situations that embody them in seeing the Salomon family live in the past and present. If one delves deeply enough and contemplates like Topol’s Patrick does, one sees the answers can only be individual and personal. No one can answer for someone else.

This is a wonderful play dramatically rendered. It should be seen, especially if you enjoy thought-provoking plays that move swiftly on emotional power. For tickets and times go to their website https://www.manhattantheatreclub.com/shows/2021-22-season/prayer-for-the-french-republic/

Prayer for the French Republic has transferred to Broadway and will run until February 18th at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre. Look for my review of the Broadway production on Blogcritics.org.

‘Chicken & Biscuits’: Delicious Farcical Fare @ Circle in the Square

In this current time of COVID when our country faces daily crises of social disunity, dangerous political extremism, economic injustice and abdication of sound public health practices by craven Republican governors, Chicken & Biscuits written by Douglas Lyons, directed by Zhailon Levingston appears to lack currency on superficial inspection. Benign family squabbles, sibling rivalry, death and succession, a same-sex relationship, such subject matter at the heart of the play is quaint fare for a comedic entertainment that offends no one.

Except Chicken & Biscuits neither lacks currency nor is a quaint, “sitcom,” family comedy. Its levity and humor smacks of farce and satire with dead-on threads of truthfulness. However, if one is dreaming, much will slip past in the twinkling of an eye in this play about black culture, family and the foundations of faith that undergird the best hope for the black American experience in a racist culture that hovers invisibly and surfaces surreptitiously in Lyons’ one-liners.

The occasion is the funeral for the father of the Mabry family. He was the pastor of a Connecticut Pentecostal-type (there is a bit of dancing in the spirit) black church. Succeeding him in the position is Pastor Reginald (played with humor and oratorical fervor by Norm Lewis). The imposing, ambitious, dominant matriarch Baneatta (the funny Cleo King) whose resume would make any ignorant racist’s head spin, stands by his side in the church family.

Gathering with their parents are daughter and son: the accomplished Simone (Alana Raquel Bowers) and actor Kenny (Devere Rogers). Rounding out the family “going home” celebration are Baneatta’s hyper vivacious sister Beverly (the gloriously out there Ebony Marshall-Oliver) and Beverly’s enlightened, wise-cracking DJ daughter La ‘Trice Franklin (the buoyant Aigner Mizzelle). To spice up the explosive, sometimes irreverent proceedings are Kenny’s Jewish lover, Logan Leibowitz (the LOL Michael Urie) and mystery guest Brianna (sweet NaTasha Yvette Williams).

Before the guests arrive Reginald counsels Baneatta to relax and not become embroiled by family machinations. We note Baneatta’s stresses when she prays to God for patience in a humorous riff about her sister. During this preamble to the funeral service, others step in and out of the vestibule. They share their hysterical misgivings and woes about the family interactions to come.

The staging at the Circle in the Square is finely employed; the flexible set design by Lawrence E. Moten III and clever rearrangement of furniture and props serve as a church basement, sanctuary, nave and more. The modern stained glass windows and wood paneling upstage center, flanked by paintings of a black Jesus and crosses on both sides, serve to create the atmosphere of a thriving church. The underlying symbolism is superb as is the assertion of freedom from the typical forms of bondage Christianity.

Each family member, an ironic stereotype of themselves, identifies the complications that will arise as emotional storm clouds threaten on the horizon of the funeral and aftermath. Kenny attempts to soothe Logan who has been disrespected and largely ignored by Baneatta and Simone who cannot brook Kenny’s being gay, nor his attraction to a Jewish white man. When we see them in action with Logan, we note their austerity of warmth with mincing words and behaviors. As they watch him founder in blackland Christendom with two strikes against him, his whiteness and his gay Jewishness, he crumples instead of standing to and giving it back for fear of offense. These scenes are just hysterical and we see beyond to the strength and character of the individuals and their weaknesses.

As Logan, Urie’s ironic, humorous complaints to Kenny when they are alone, set up the tropes and jokes which follow as we watch how Baneatta and Simone treat him like a rare breed of exotic who must give obeisance. Hysterically, Kenny breezily abandons Logan to their clutches: it’s sink or swim time for Logan. Urie plays this to the hilt authentically, riotously with partners, King and Alana Raquel Bowers as the straight women who “bring it.” Watching this is both funny and upsetting. The women are intentionally clever. Their response is anything but Christian, loving and warm, but who is playing whom? We are reminded of the hypocrisy of evangelical churches to the LGBT community who engage in political Republican actions. Though this is a church in Connecticut and its members are most probably Democrats, the similar odor is clear. We wonder, can the situation evolve for the better? Can they achieve common ground?

The only one who accepts Logan with Christ’s unconditional love and hugs is Pastor Reginald. And Logan longingly remembers that Reginald’s Dad (who we discover to be a waggish, wild pastor) showed the same love. For Logan it is no small comfort, but apparently this open behavior was typical of the deceased pastor’s liberalism and Christian equanimity.

Obvious is the clash between lifestyles and personalities of the sisters: the educated achievement-oriented Baneatta, and the wild, flashily dressed, divorced and “out-there” Beverly and her DJ, hip, savvy, “ready for her social media celebrity” La ‘Trice. Mother and daughter counsel each other to “shut it,” projecting widely but not seeing their own faults and outrageousness to care to change. They do it because they are funny and they laugh at themselves. Do they have anything better to do being who they are? Marshall-Oliver and Mizzelle make for a great mother-daughter team.

Truly, the women dominate this world as the service, the sermon and eulogies get underway. Their behaviors and actions are at various proportions of farcical and funny as are all these typical, atypically drawn individuals.

Nevertheless, underlying the laughter and stealthy ridicule of each character being themselves, we get the importance of family and faith community. Despite the miry clay conflicts that emerge as part of the whirlwind of events that race through the play to the end revelation, these individuals have each other’s backs. And entry into the family, as Logan discovers, is not easily won. However, when it’s won, it’s forever.

The service is down-home (different from evangelical) with the hope of less hypocrisy via a more spiritual relationship with God. Thus, when the Pastor preaches in the spirit and dances a bit in the spirit, the audience even takes up the “Amens” in concordance. Indeed, the hope of a better way flows from Pastor Reginald’s fountain of faith. And by the conclusion of Chicken & Biscuits, a better way has been found in the dynamic of each of the family relationships, catalyzed by a mystery guest that Baneatta feared and kept secret for most of their lives.

Chicken & Biscuits serves on many levels. For those who enjoy a riotous comedy/farce with characters that tickle one’s funny bone continually, this is the perfect play. For those who enjoy being entertained, yet also enjoy the illumination that comes when thematic truths about life and people are cleverly revealed without preachy presentments, then this play surely delivers. For those who value the unity of family that never devolves to hatred, division, anger and bitter insult and rancor, the play is a portrait of a black family which resonates through the medium of satire and good will.

Kudos to Nikiya Mathis for her hair/wig and makeup designs: I loved her cool hair design for La ‘Trice, and Baneatta’s sober, contrasting hair and hat, to Beverly’s unsanctimonious hair and feathery headpiece. Simone’s hair design was just luscious. And additional kudos to Dede Ayite’s great, character revealing costume designs, Adam Honoré’s beautiful lighting design and Twi McCallum’s sound design. Their assistance was superb in making this a wonderful romp with circumspection if you divine it.

You need to see Chicken & Biscuits for the cast’s excellent ensemble work, Levingston’s direction and Lyons’ uproarious writing. In all its satiric humor about family “types,” the production took me away from divisive political rancor and stereotypes that follow. Chicken & Biscuits is a welcome joy. For tickets and times go to their website. https://chickenandbiscuitsbway.com/

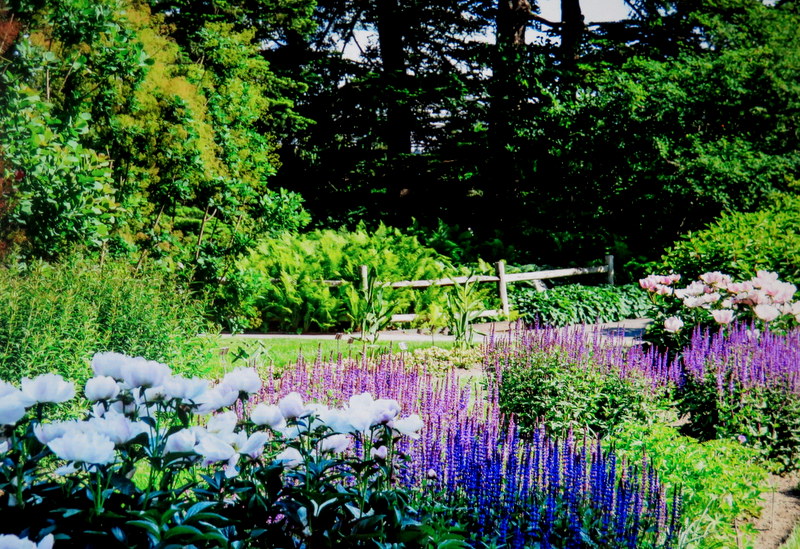

New York Botanical Garden is Reopening The Outdoor Gardens and Collections to the General Public July 28

New York Botanical Garden, Reopening New York Forward Phase Four (NYGB)

Today, The New York Botanical Garden announced its schedule to reopen the outdoor gardens and collections of its 250-acre site to the general public on Tuesday, 28 July. The process has been a gradual one as New York City achieves New York Forward’s Phase Four which is projected to begin 20 July. The Garden’s reopening plan is mindful of protocols that pertain to businesses and cultural institutions. It follows CDC guidelines regarding protecting visitors from COVID-19 transmission. The Garden’s protocols involve safety measures that encompass State and City requirements and OSHA requirements.

New York Botanical Garden, Reopening New York Forward Phase Four (NYGB)

As a part of Appreciation Week July 21-26 the New York Botanical Garden is welcoming Garden Members and Bronx Healthcare Heroes from the eight public and private hospitals in the borough. Also included are Bronx Neighbors with “first access” and complimentary tickets for free admission. This reopening including “Appreciation Week” is contingent upon Governor Cuomo designating New York City as fulfilling the requirements for the Phase Four opening.

New York Botanical Garden, Reopening New York Forward Phase Four (NYGB)

All visitors, including Members, must purchase or reserve timed-entry tickets in advance. All visitors must be wearing masks.

APPRECIATION WEEK REOPENING is from July 21, Tuesday – July 26, Sunday from 10 a.m.-6 p.m. GET TICKETS BY CLICKING HERE

New York Botanical Garden, Perennial Garden, Reopening New York Forward Phase Four (NYGB)

Through its Appreciation Week initiative, the Garden acknowledges its gratitude and recognizes the dedication, strength, and resilience of Bronx frontline health care workers and residents. These are the workers that residents remember daily around 7:00 pm with cheers, shouts and a clamor of pots and pans for their great sacrifice to help patients through the terrible journey of overcoming this virus which is still not understood. Complimentary admission for those groups will continue through September 13.

New York Botanical Garden, Seasonal Walk, Reopening New York Forward Phase Four (NYGB)

New Yorkers will be coming from all the boroughs to seek respite and renewal at NYBG. They have gone through a hellacious time (characterized by Governor Cuomo) these past months sacrificing under quarantine. Together, all New Yorkers were united, disciplined, smart, tough and loving as they confronted an unprecedented crises in their lifetimes and brought the highest COVID infection rate in the world to one of the lowest in the nation.

New York Botanical Garden, Home Gardening Center, Reopening New York Forward Phase Four (NYGB)

The Garden is the place to be in July. It is one of the most gorgeous, historic and extensive botanical gardens in the world. Not only is it an urban oasis, it is a cultural, living artifact which has become a moral imperative, a haven for every season, and a New York City treasure anchored in the Bronx. Currently the Garden landscape features vibrant daylilies, hydrangeas, water lilies, and lotuses among its one million plants. Walking paths and trails crisscross the Garden providing opportunities for discovery through encounters with nature.

New York Botanical Garden, Thain Family Forest, Reopening New York Forward Phase Four (NYGB)

FOR YOUR SAFETY

The Garden has a TIMED ENTRY. FACE COVERINGS ARE REQUIRED. There is SOCIAL DISTANCING.

There is CONTINUAL CLEANING AND DISINFECTING. There are DAILY STAFF HEALTH CHECKS.

New York Botanical Garden, Peggy Rockefeller Rose Garden, Reopening New York Forward Phase Four (NYGB)

Know Before You Go

- Reduced Garden capacity and amenities. For the safety of visitors and staff, NYBG closed indoor spaces and any collections where social distancing is not possible. Water fountains and bottle refill stations are deactivated. Please bring your own water, or purchase water at the Pine Tree Café.

- Enhanced cleaning and disinfecting practices. Garden staff are sanitizing surfaces such as tables, handrails, and door handles regularly.

- Sanitization stations. Hand sanitizer has been placed throughout the Garden. All visitors and staff must practice proper hand washing procedures.

- 250 acres to explore. Enjoy seasonal highlights in the Chilton Azalea Garden, Native Plant Garden, Perennial Garden, Conservatory Courtyards, Rockefeller Rose Garden, and most other outdoor collections and trails. Dress for the weather and wear comfortable walking shoe

New York Botanical Garden, Water Lilies and Lotus, Reopening New York Forward Phase Four (NYGB)

- Grab-and-go food service only. Limited food and refreshments are offered for carry-out at the Pine Tree Café. Outdoor seating is available.

- NYBG Shop is open. The Garden has adjusted shopping and checkout processes to provide the safest possible experience.

- Mobility considerations. Wheelchair loans and the Tram Tour are suspended. If you require a mobility device, we ask that you bring your own.

‘Parity Productions Champions Women and Transgender Artists’

Through the window onto a new reality. Parity Productions launch was hosted by Janos Aranyi and Theresa Llorente in their beautiful home overlooking Gramercy Park. Photo by Carole Di Tosti

Criticism of women advocating for equal pay, equal voice and equal command over their destiny has been easily dismissed by men and their willing women sycophants who have slimed women with the “F” word as “feminist” ideologues. Any momentum to provide women with the opportunity to excel has always been demeaned as “unnecessary” and has been met with resistance.

That is as it should be. Resistance is more productive than hypocritical co-optation which lulls individuals into believing they have made progress when actually they have been running the perimeters of zero.

In the arts, in live theater and in film there has been tremendous resistance to hire women behind the scenes as directors, playwrights, designers, technicians, et. al. And gender inequality is rife in front of the camera as well, with male dominated film subjects, lead characters, stories and well funded blockbusters taking all of the pie and male dominated companies reaping heavy proceeds leaving the crumbs to women lackeys lining up at the back of the bus. (Jennifer Lawrence is in a minority of one with few female colleagues even nearing her status)

A recent Variety article identified gender inequality is not only a plague in the US film and entertainment industry but it is as endemic in Europe as well. If we don’t understand why and how this has happened, we stand the chance of never equalizing gender roles in the arts.

There was a cocktail hour where guests mingled and were welcomed by Ludovica Villar-Hauser and her team of collaborators at Parity Productions.

Paul Feig (Spy, Bridesmaids, Ghostbusters), who was honored at the 6th Annual Athena Film Festival with their “Leading Man Award” because of his outspoken stance and support for women, spoke about the under-representation of women in the arts. He labeled it as the “banality of evil.” In other words this has not been an overtly “wicked” and intentional act on the part of men in power.

Feig implied that gender inequity has been borne out of negligence, out of a lack of attention to necessity…the necessity to recognize and reward women for their incredible talents and contributions. That banality is part of the continuance of gender dominance and the comfort of the “young/old boy’s network,” which speaks a “common language” as it comfortably objectifies women. It is these issues and others that have spurred on an unconscious dismissal of women and the passing over of those who are not ready gender cronies.

As for those who have an active mentor or help-meet to give them the 10 legs up they need to begin to compete? There are vastly too few men willing to act as mentors. Women are the ones who must mentor each other as has been occurring with conferences like Women in the World.

Opening remarks by Founder and Artistic Director of Parity Productions, Ludovica Villar-Hauser. Photo Carole Di Tosti

Indeed, the government is taking notice. There has been a call to investigate gender discrimination against women directors in the film industry which hopefully will be carried over into theater and the entertainment arts, though the recent cry has been that things have been getting better for women in the theater. Really?

Thanks to the resistance in the entertainment industry, whether intentional or not, women are joining advocacy groups and creating their own teams to combat the gender inequality in the entertainment arts like never before.

We Do It Together is an example of a global non-profit which has been created to finance and produce films centered around women and dedicated to the empowerment of women.

Others groups like Parity Productions are NYC based with a global reach. They are organizing and strengthening themselves with unity and coherence of purpose by establishing their own opportunities increasing women and transgender representation in the arts so that gender equality is the rule, not the exception.

(L to R): Ludovica Villar-Hauser, Founder and Artistic Director, Parity Productions, actress Elizabeth Jasicki, getting ready to present from her one woman tour-de-force ‘Village Stories’ at the Parity Productions launch. Photo by Carole Di Tosti