Category Archives: NYC Theater Reviews

Broadway,

‘The Kite Runner’ Resounds With Poignancy and Profound, Personal Intimacy.

Rarely in life do we have the opportunity for second chances, to reverse the most dire, pitiful and hateful moments of our lives and transform them with aching hope toward acts of kindness, decency and courage. This resurrection of hope toward faith in God is integral to Matthew Spangler’s adaptation of The Kite Runner, based on the best-selling novel by Khaled Hosseini, currently running at the Helen Hayes Theater on 44th Street in New York City.

Acutely, The Kite Runner is a story of relationships. These abide between father and son, between servant and master, between friends who are in fact brothers. There is also the relationship the individual has with himself. In the instance of the protagonist Amir (portrayed with aplomb and fearless generosity by Amir Arison), this relationship reveals his struggle as a divided self, unable to overcome his sin of cowardice, fear and guilt that leads to self-betrayal and betrayal of those who love him.

In the play the relationships are further tested against the backdrop of a an economically, culturally and politically roiling Afghanistan, where Pashtuns (Sunni Muslims) have historically oppressed Hazaras (Shi’a Muslims). When the monarchy, which has managed to control the economic, religious and political divides eventually topples in 1975, chaos follows. This chaos spawns the major conflict of the play as Pashtuns and Hazaras attempt to survive in the new political landscape.

However, before that de-stabilization occurs, we witness the peaceful, prosperous life of Amir with his father Baba (Faran Tahir), though Amir feels that sometimes his father hates and despises him as a weakling. Baba is a wealthy businessman, who retains his servant Ali (Evan Zes), and his son Hassan (Eric Sirakian), like members of his family for forty years, despite their being lower class Hazaras. Baba and Amir are non- practicing Westernized Pashtuns. Years later when Amir returns on a mission of redemption and forgiveness, an Afghani driver characterizes him and Baba as “tourists,” superficially Afghani. Since Baba raises Amir without attention to strict religious observances and pretensions about class, the closeness and love between Baba and Ali and their sons is heartening.

In fact the beautiful friendship the boys have in a then peaceful Afghanistan is so well acted by Arison’s Amir and Eric Sirakian’s Hassan, that we nearly forget Amir’s warning comments at the top of the play, “I became what I am today at the age of twelve. It’s wrong what you say about the past about how you can bury it, because the past claws its way out.” Amir, who narrates throughout makes these comments in San Francisco almost twenty-five years later as a warning salvo before he relates the flashback of haunting events with Hassan. These are events with which we identify because of their intense poignancy and emotional grist that transcend culture, language, religious and classist differences. These seminal and particularly resonant scenes of Amir’s life with Hassan, fly like kites to the heart of our shared human experiences, revealing psychic flaws and mortal humanity.

After Amir’s warning comments, director Giles Croft’s vision of an idyllic, happy Afghanistan before the political upheavals is poetically suggested and elucidated as Amir’s wistful memories with the ensemble onstage. Croft employs the kite and sail metaphor in the props and scenic design to link Amir from the kites he watches being flown in San Francisco in 2001, as the threaded memory that brings him back to his time in Kabul, Afghanistan in 1973.

Arison takes on the mannerisms and stance of a younger self as he plays “cowboys and Indians” with his friend Hassan, who importantly remains the same age throughout the play in his enthusiastic, vibrant and noble self. Of course, this is as it must be because this is Amir’s memory of Hassan, who disappears, never to be seen again, after the negatively defining incident that impacts Amir’s life for twenty-five years.

Tabla Artist Salar Nader provides the melodic drumming as Arison’s Amir narrates and steps in and out of the action seamlessly against Barney George’s minimalist scenic design, a fence, enhanced by William Simpson’s projection design and Charles Balfour’s lighting design. These artistic elements effect various places along Amir’s journey into self-torment which takes him from Afghanistan to the US, then back to Afghanistan and back again to the U.S.

Croft establishes the setting in the flashback as an elusive but powerful memory. Spangler uses the dialogue in Farsi as Amir and Hasan play, which conveys the beauty of the time and the poetic rhythms of the language. It is rarely used afterward, except for an exclamatory effect or a “hello” or “goodbye.” We enjoy the bond of these two boys who have gone beyond their classes and religions to find the spiritual element which always remains but which Amir loses after his self-described sin and act of infamy against Hassan, Ali and Baba. But caught up in the joy of their youthful and free relationship, we forget what Amir says that he buried in his past that claws him back. We join them in play, as the literate Amir carves their names in a pomegranate tree as the Sultans of Kabul. And Amir reads to Hassan from a favorite story about which we discover later ironically relates to Hassan’s and Amir’s relationship to Baba.

We get a flavor of this pleasant Afghanistan from these elements along with the two pieces of patterned curtain arranged prettily as two halves of a sail reminiscent of a kite as a backdrop for certain scenes. Amir familiarizes us with his relationship with Hassan as his friend who is one year younger. Yet, he indicates that always there is the distinction that Hassan is a servant, though Baba appears to love him, showering him with the same presents for his birthday that Amir receives. One gift we see is a cowboy hat which, of course, Amir has to put on and wear also.

Like two peas in a pod, the boys are motherless; Amir’s mother died giving birth to him, which Amir credits being one reason for Baba’s anger at him. And Hassan’s mother ran away to join a troop of actors and musicians, which was a fate worse than death in Afghanistan. Thus, both fathers must raise their sons without wives, though Baba has girlfriends and comes home late ignoring Amir who is lonely and insecure. Amir’s sole comfort comes from his friendship with Hassan. On the other hand, Ali is always there for Hassan, who has an inner core of strength, love and confidence.

Spangler’s characterizations run deep and the actors make the most of the nuances in conveying the explanation of why Amir behaves as cruelly as he does. Though Hassan demonstrates love and faithfulness to Amir, whom he considers his best friend, Amir is incapable of returning this honor. Thus, as the myth goes, when Hassan learned to speak, the first word he said was “Amir.” For Amir the tragedy is that he has to understand and accept the love and faithfulness that Hassan has for him. He doesn’t. To our chagrin, though Arison makes Amir likeable, we discover that Amir is incapable of showing love and loyalty to anyone. So when the boys meet up with Assef (Amir Malaklou), a bigoted Pashtun bully, Amir behaves like a coward wussy, while Hassan fearlessly protects them both with his attitude, his innate courage and confidence. Also, he is a crackerjack with his slingshot which helps save the day.

Crofts stages the kite fighting tournament as the high point of Hassan’s and Amir’s relationship with excitement and verve, as the actors pantomime the cutting of the kite strings. Hassan, as the best kite runner, anticipates where the last “enemy” kite will fall. Securing that kite will be the prize that forever emblazons Amir and Hassan as the best team at kite fighting. However, when Hassan runs after the blue kite, Asseff and his gang intercept him. Asseff cannot brook losing the tournament to an unworthy blood polluted Hazaras. To punish and humiliate Hassan, he demeans him sexually in a cultural defilement and sin, which Amir hears happening from a hidden position. Amir is too frightened to help Hassan beat off the gang, because he believes himself to be too much of a wussy to stand up to Assef’s tyranny. Amir runs away, embarrassed and ashamed. What would Baba think?

After this incident on the day that Amir achieves his father’s praise for winning the tournament, he is desolate. Amir yearns for an elusive peace and freedom from guilt and self-torment in not helping Hassan. Amir’s sin of cowardice and lie of omission blossoms into overwhelming self-recrimination that causes him to project his self-hatred onto Hassan. Rather than to face the truth of his own inner weakness, he accuses Hassan of theft, one of the worst acts Baba says a man can commit. When questioned, Hassan admits he has stolen to protect Amir from Baba’s wrath, because both Ali and Hassan understand the reason why Amir has dishonored them.

Baba forgives Hassan the theft and expects Ali and Hassan to go on as before. However, Ali and Hassan leave the household to maintain their honor. Ironically, Amir is even more ashamed of his wickedness because once again, Hassan has protected him out of the strength of sacrificial love in a move that is Christ-like. Amir’s is a monstrous act because Hassan the younger, the “low class” Hazaras is the more honorable, kinder and more loving person. Amir must face that he is a two-fold liar, a coward and an unworthy human being.

Amir’s unconscious guilt and self-recrimination consign him to a life of self-torment, until he allows himself to be redeemed by a call from Baba’s former business partner Rahim Khan (Dariush Kashani) who tells him, “Come see me. There is a way to be good again.” This is the opportunity to make amends to Hassan’s son Sohrab. Wisely, Croft casts Eric Sirakian as Hassan and Sohrab. Sirakian is absolutely terrific in both roles. And in Act II when Sohrab begs not to be taken to an orphanage where he will be harmed, he breaks your heart.

Interwoven in the relationships of Spangler’s adaptation are all the Shakespearean verities and vices elevated: sacrificial love and forgiveness, betrayal of self and those closest to us, unforgiveness, sadism and wanton cruelty leveled on an innocent who sacrifices himself for love and friendship. And these processes are pitted against the fateful opportunity to reverse the course of personal destiny and transform self-loathing to empowerme,nt, love and acceptance. Amir eventually is brought to his second chance in Act II. Interestingly, it is the time of the Taliban ascendancy to the point of despotic tribalism and murder.

Though he doesn’t believe in the religious observances, Assef’s bullying psychotic nature has found its true purpose to torture and kill in Taliban Afghanistan. That Amir must face his old demons of guilt, cowardice and fear to confront his nemesis Assef, fight him and escape with Sohrab, who Assef has kidnapped, is an incredible journey toward Amir’s personal closure and reconciliation with God.

If anything The Kite Runner underscores Amir as an Everyman, who reaches the bottom of his own personal abyss to seek forgiveness which helps him understand the meaning of “brotherly” love, the sacrificial love that his childhood friend Hassan (the marvelous, heartfelt Eric Sirakian) unquestioningly, gracefully bestows upon him.

This imagistic, stylized production fades in and out of the epic in its cultural scope and breadth of events that take place between 1973 and 2001 in Afghanistan from monarchy, to republic, to communist coup, to Russian invasion, and Taliban takeover. Amir’s journey moves to Pakistan and San Francisco then back and forth again. With brief phrases of language at the beginning and sprinkled here and there, that reflect cultural authenticity, the fateful story emerges. Amir narrates and we witness vignettes that explore Amir’s evolution as a worthy human being. Arison does a yeoman’s job with a challenging role that spans decades and keeps him onstage until the intermission, then brings him back until the conclusion. With the music of the tabla drums, the singing bowls and the schwirrbogen, we find the rhythms of the culture always pulsating, to remind us of the vitality of history and ancestry.

This is a fine adaptation and resounding, soulful production whose themes are immutable and current. Praise goes to the ensemble and Giles Croft who shepherds them to move like a synchronized pageant. Kudos goes to the Drew Baumohl (sound design), Jonathan Girling (composer and music supervisor), Kitty Winter (movement director) and Salar Nader (tabla artist and additional arrangements), as well as the other creatives previously mentioned.

The Kite Runner is at the Helen Hayes Theater for a limited engagement that ends 30 October. This is one not to miss for its acting, its stunning vibrance, poignancy and heart. For tickets and times go to their website: https://thekiterunnerbroadway.com/

‘Chains,’ an Exceptional American Premiere by Mint Theater Company

The Mint Theater Company resurrects worthy playwrights that haven’t been produced in decades. Before COVID-19 upended their plans the company scheduled two productions of Elizabeth Baker’s works (Chains, Partnership) for the summer of 2020. After the dust settled the company revised their plans for the summer of 2022 and decided to first present Chains in its American Premiere. Later, the Mint Theater Company will present Partnership. At some point they will offer the three Baker plays The Price of Thomas Scott (produced in 2019) Chains and Partnership in an online Streaming Festival so that global audiences might become familiar with the exceptional, profound playwright who was certainly a maverick ahead of her time.

Elizabeth Baker (1876-1962) wrote Chains in the early 20th century, though the themes and issues Baker has her characters confront are current and identifiable with our time. Running at Theatre Row until 23rd of July, the Mint’s production of Chains must not be missed for its acute attention to details of setting, as well as the superb direction by Jenn Thompson (award nominated for Women Without Men, 2016) who has teased out striking performances from her cast. Their ensemble work is authentic and forceful.

Baker’s play focuses on the problems of London’s working classes (clerks, shop girls, etc.), their aspirations pitted against the trials of insecurity, workplace competition and the doldrums of career immobility. In its centrality Baker highlights not only issues of class, but those of gender, economic inequality, immigration and the difficulties of economic upward mobility. Subtly, Baker alludes to the strains between workers and employers. Though the word “union” is not mentioned, the “S” word, “socialism” is referred to once or twice jokingly by the characters as a negative. Nevertheless, the dull, work atmosphere, oppression and owner hostage taking that some characters refer to would be mitigated by unions to equalize the power dynamic with owners.

Using the backdrop of married couple Lily and Charley Wilson (Laakan McHardy, Jeremy Beck) and their extended family, the conflict initiates when the couple’s border and Charley’s work colleague Fred Tennant (Peterson Townsend) announces his plans to leave the boredom of his clerk position and take off to Australia for a change of scene and career. This simple announcement upends Charley’s perspective about his own life and brings to the surface his dissatisfaction with the drudgery of his career and the constraints of his married life.

Additionally, it encourages and inspires Maggie Massey (Olivia Gilliatt) Lily’s sister, to rethink her own plans for her life with her future husband, as she yearns to have the independence that men have to travel and pick up roots and settle wherever they like. Though fiance Walter Foster (Ned Noyes) is a generous and well-off partner who would give her independence with his money if they married, Maggie is unsure that marriage with Walter is right for her.

This is extremely novel for her generation and gender. Folkways stipulated that women marry well-off men, be provided for, keep house, raise children and be contented to shut up, not make waves and not be ambitious or creative. Maggie views Lily’s and her mother’s lives and questions if she “loves” Walter enough to be bound to him forever, when she may be happier on her own, expressing her talents. Or perhaps she may find and love another.

Thus, Baker cleverly explores the themes of security and safety for both the men and women (then and now) who have chosen either to take risks or remain stuck in a life of mediocrity and misery, whether single or married. As Charley’s neighbor Morton Leslie (Brian Owen) suggests, leaving behind one’s secure boring position and comfortable, familiar life holds tremendous risks for Tennant, for anyone.

Against the romanticism of leaving, various characters throughout the arc of the play’s development pose questions about Tennant’s choice which appears to upset them because it is particular and uniquely not their experience. They ask the following. Will he be able to get a position to support himself easily in Australia, when there are so many thousands looking for employment? What if he fails? What if he proves to be an embarrassment to himself and has to return home to be closed out of his career prospects?

Indeed, Morton Leslie ridicules Tennant’s ambitions and ideas to his face. He insists jokingly, though he is very serious, that Tennant is going to fail. Eventually, this is echoed by others in Charlie’s sphere of influence, including his in-laws (Anthony Cochrane, Amelia White). Lily expresses her upset at Tennant’s leaving because they need his rent. So Tennant’s decision proves economically trying for them, adding instability to their lifestyle. Meanwhile, Lily’s brother Percy (Avery Whitted) at a young age plans to marry Sybil Frost (Claire Saunders) following in the footsteps of what is expected for a young man. This is even after Charley warns him to wait and consider the future because he is too young. In an interesting turning point, Charley tells Percy that he married too young.

On the other side of the argument about why it’s good to take risks, Tennant explains his rationale to Charley. Unlike Charley and the others, Tennant is not married with the burden of having to take care of a wife and children. He is independent, young, makes his own decisions and has no family ties or responsibilities. He has friends, but can make friends anywhere, as he is sociable. So fear of uncertainty has been overcome. He is more afraid of remaining stuck in a miserable position at his job that has little upward mobility.

Thus, if he leaves England, he leaves the class system, the varied oppressions by owners, the stultifying atmosphere of the workplace and the lack of challenges. For him, anything will be possible and only he will stand in the way of that. Leaving, he will learn to redefine himself and seek out a different identity. His excuses and blaming others for his condition will fall away; he will evolve stretching his talents and abilities. The incredible power and courage of Tennant’s decision amazes because he is ending a nullifying pattern before it becomes too entrenched in his soul to escape it. He recognizes and appreciates this knowledge; the others fear it or are blind to it. We empathize with his situation of wanting to seek a better life in another country. It is historic and symbolize the longing of the spirit to evolve from stasis.

Charley has the self-knowledge to understand what is at stake beyond material, pragmatic considerations as does Maggie. They credit Tennant’s decision. The irony is clear. The more the others question and challenge Tennant’s fool-heartiness, the more we realize their fear, their mediocrity, their acceptance of their condition which may be tantamount to a form of slavery. The theme is metaphorical and profound, and Baker nails how difficult behavior change can be when one keeps adding daily to the links in the chain of sameness in one’s life.

When Charley gradually discloses that he agrees with Tennant’s desire for a more fascinating life, the conflict between him and Lily and her family grows. Herein lies the main theme of the metaphor of chains. On the one hand, a secure position chains individuals from falling into the abyss of dissolution and bondages. These include fear of uncertainty: of confronting treacherous risks; of failing and never recovering from poverty and its ills. On the negative side, security deadens one to being adventurous and the chains of miserable dullness hold individuals to a bondage of their own making. Soon they believe they can’t take risks or it is too late to be an adventurer when one is older. Thus, severing the chains of security that bind the inner adventurer to the hackneyed, uninteresting, uncreative, unchallenging existence becomes impossible.

As an example of the terror of atrophying at work Baker introduces the character of Mr. Fenwick (Christopher Gerson) an older employee at the firm where Charley and Tennant clerk. Fenwick visits Charley and affirms Tennant’s decision is a wise one that he, at his age, could never take. And when he announces that there is some question about receiving their bonuses for the year, all the arguments about the benefits of time off (three weeks, a day on the weekend) go out the window.

Indeed, the employees are at the mercy of their employers/owners who can do as they please. There is no guarantee about work conditions and salaries. The propaganda against socialism was rife during Baker’s time as Morton Leslie suggests mocking “socialism.” Baker subtly reveals that such propaganda picked up by louts like Leslie keeps the society in line to produce workers who are “well-oiled,” uncomplaining machines. As for those like Tennant, who would challenge their work conditions? The social culture discourages their ambition or desire to want something better or to break free and move into a more productive, satisfying life. Meanwhile, Maggie’s situation is more complicated with heavier strictures on what opportunities are available to her.

Director Jenn Thompson shepherds her actors to highlight the conflicts, issues and themes in this extraordinary play which resonates for us today in a myriad of ways, politically and socially. Specifically, the actors portray without stereotyping the individuals they inhabit. These characters divide into two camps; those who agree with Tennant (Charley, Maggie) and those who do not.

Townsend’s Tennant seduces Beck’s Charley with his immigration plans, so that Charley can think of nothing else. Jeremy Beck imbues Charley with concern, confusion and distraction with increasing intensity until he reveals his plans to leave for Australia which upend Lily. We know it is coming and we wish him to be successful. And we believe what Lily does not, that he will make a way for her and send for her, after he has made his way in Australia. All she can do is weep; she is devastated.

The tensions that Thompson strives to create with Beck’s superb acting and McHardy’s heartfelt response and sense of doom raise the stakes and bring us to a confluence of feeling. The ending may be controversial, depending upon the audience viewer. Indeed, Thompson has helped to strengthen the brilliance of Baker’s work and reveal her to be a playwright worth revisiting again and again.

The production succeeds from start to finish thanks to the creative team. I particularly enjoyed the actors helping morph the set from the Wilson’s home in Hammersmith to the Massey’s house in Chiswick and then back again. Incorporated into the theatrical experience of the production, it was seamless. Just terrific! Kudos to the following creatives: John McDermott (sets) David Toser (costumes) Paul Miller (lights) M. Florian Staab (sound) and the others that made Thompson’s vision for Baker’s work to come alive.

I cannot praise this presentation enough. COVID-19 was a devastation we have yet to overcome and deal with emotionally and psychically, perhaps. On the other hand this production was worth the wait, well chosen for our time. Go see it. For tickets and availability to Chains that plays with one intermission go to: https://minttheater.org/production/chains/

‘Corsicana,’ Will Arbery Tackles a Kinder, Gentler Texas

Will Arbery’s Corsicana directed by Sam Gold in its world premiere is more an evocation and memorial to these representative characters of the heart’s universal weirdness, who try to find comfort and make their own space in the world. Unfettered with glamor and starlight, Arbery’s portrait of humanity in all its endearing strangeness is one we can easily identify with.

The play’s progression moves slowly by degrees of the stage turn table fitted with two couches. This revolves when the time/space continuum shifts and scenes change. The large couches and a small table and chairs downstage are the only furniture in a white-walled warehouse of a structure that represents the house where the two siblings Ginny (Jamie Brewer) and Christopher (Will Dagger) live and where neighbor and friend Justice (Deirdre O’Connell) visits. With a plexiglass framed roof that the characters slide forward, Lot’s (Harold Surratt) barn emerges as the lights upstage dim and the characters step downstage in the light, signifying Lot’s property when they visit him.

The actors do a phenomenal job revealing the inner and outer emotional filaments, quirkiness and complications their characters experience during their interactions with one another. Arbery’s central focus of Corsicana, finely directed by Gold, is on Christopher and Ginny, aged one year apart. They have recently lost their mother. Feeling adrift in their mourning, they awkwardly reposition their identities and relationship with each other, haphazardly shuffling toward a new respect, love and understanding without their mother’s buffer of love.

Will Dagger’s Christopher is humorously chided by his sister Ginny (Brewer) a smart, sharp-witted thirty-four year old woman with Down Syndrome, as they sit and plan the rest of their lives turning over Christopher’s initial question about Ginny’s unsettled unease. As they discuss the state of themselves in their loss, we understand how much their mother meant to their sense of purpose and being. Living in the house she left them, they are in stasis, not engaging in their previous lives with work and friends. Ginny can’t find interest in taking up her hobbies, choir or her job. Mourning is a tricky business. When does one return to one’s life? Can one return? Should there be new engagement immediately afterward?

They are displaced in a limbo between losing an old life and negotiating a new one, their hearts glazed over in non-feeling.. It rather seems they are plopped down together for our own good pleasure to understand how siblings close in age in adulthood (Christopher is thirty-three) might get along, when one of them is not living in a group home, but is being “taken care of” by family and a close friend. However, when Ginny asks Christopher’s help in finding something for her to become engaged in, he understands that it must be something novel. All of her previous pursuits don’t satisfy. And she affirms that she is proud, so asking for his help is the last thing she wants to do, but desperately must do.

From their discussion and Ginny’s listing of wants and wishes, we discover that Ginny did many things with her mother. And when family friend of their mother. Justice (Deirdre O’Connell) drops over with groceries and a chat from time to time, we note that she is willing to stay with Ginny, baby-sit her, though Ginny bristles at the reference and loudly affirms she is an adult. Of course she is, but there are boundaries that she crosses unwittingly as we see with her attempt at friendship with Lot. Thus, clearly, Ginny relates differently, from a unique frame of reference, perspective and response to others that is uniquely her own.

Indeed, Jamie Brewer’s Ginny seems extremely adept and mature enough to take care of herself which is where her relationship with her brother may end up, in separate houses, lives, spaces. Steps must be taken, so of course, Christopher tries to help. The conflict of “how to help Ginny find something to do” blooms in full force when Christopher visits Lot, an artist that Justice recommends because she knows him and has even collected some of his work that might be exhibited, if the situation pans out. In the interim Lot works on a project he won’t let anyone see that thematically manifests as “a one-way street to God.” Clearly, he is secretive and religious and private, and shares those similarities with Ginny who believes in God and is so secretive she refuses to allow anyone into her room because she values her privacy.

In the hope that Lot might help Ginny express her musical talent and come out of her current doldrums with a sense of purpose and collaboration, Christopher visits the artist and after some humorous repartee which Arbery is a master of, Lot agrees, but she must come to his place. Lot’s demeanor is straightforward and no nonsense, revealing a brilliance and wisdom. Arbery also plants seeds of Lot’s story in his upset to hear that Ginny is “special needs.” He questions if Christopher thinks he is that way, too. His question is out of left field, but intimates the story which he unfolds in the conclusion of the play, a story whose revelation to Justice reveals he is ready to take their relationship into something more than friends.

Christopher’s cajoling and friendship with Justice (we never find the symbolism of her name, though she is the balancing force among the characters) peaks Lot’s kind approval. He refuses money, but would like a gift as payment, throwing in a philosophical comment about materialism and waste which he and Justice eschew. What the gift is remains a mystery, but as God bestows talents, Lot indicates an acceptable gift would be an expression of someone’s talent at the appropriate time. Turns out, he receives his gift at the play’s conclusion when all contribute their gifts in a song which, as it turns out, has been written by the characters responses, feelings and issues throughout the play. Indeed, the play is the theme song of their humanity that they sing at the end followed by audience applause.

Lot’s appreciation and closeness to Justice is revealed when she visits and they banter, again with Arbery’s talent for pointed, humorous dialogue whose sub rosa content shines through. She tells him “shut up,” and not stop her relating a fascinating, symbolic dream about a dead man who haunts her. And he tells her repeatedly she’s “weird.” But they are birds of a feather, though Lot is noncommittal at this point.

When Ginny visits, Lot attempts to find something interesting to sing about and collaborate on. As Lot tries we note his cleverness and creativity with an amusing story that includes dinosaur ghosts. However, though most “children” and individuals would be interested, Ginny isn’t. Eventually, she expresses her interest in pop music and singers who Lot is unfamiliar with. Their discussion comes upon a dead end until Ginny expresses something which is untoward to Lot and something which she doesn’t realize is a trigger for him. What she expresses upsets Lot who affirms he can’t work with her and who dismisses her. She is perplexed.

In the next segments of the Second Act the revelations of why Lot reacts as he does come to the fore. The unsettled issues of Ginny’s “untoward” response to Lot, her unwitting comments to him about Christopher, and Justice’s feelings about Lot are resolved in Arbery’s exotic dialogue that is out there and ethereal but grounded in undecipherable, spiritual human consciousness and experience. Christopher, Justice and Lot have exceptional monologues beautifully delivered by Will Dagger, Deirdre O’Connell and Harold Surratt. That the audience was breathless and silent and the annoying barking seal in front of me was mesmerized through all of them, indicates the depth of authenticity the actors effected to make such profound moments “take our breath away.”

Arbery’s Corsicana is not like his other plays. That is a good thing. It is humanity, unadorned, quixotic, exotic in its peculiarity with these amazing characters warmly, lovingly inhabited by the ensemble whose teamwork is right-on. Gold’s direction infuses the characterizations with haunting absences of time and space reflected in the set design (Laura Jellinek, Cate McCrea) and efficient, suggestive lighting design by Isabella Byrd. Sound (Justin Ellington) was at times in and out perhaps because of the acoustics in the theater or the actors not projecting when their backs were turned to the audience. Not every word was sounded in clarity, whether a fault of the hearer or the structure of the theater, projection or something else. However, the monologues, because of their importance, were bell clarity sensational. The repartee and quips sometimes were thrown away into deep space heard by elves.

Finally, a note about the music which was characteristic of the characters’ souls thanks to Joanna Sternberg and Ilene Reid music director. The song at the end, the gift that Lot receives, is endearing, humorous and fun. Sung in collaboration, the unity and community that the characters achieve is poignant. Of course that they all have faith in God, not a specific political faith. But spiritual understanding threads throughout the song, which is in sum, the play. That their type of deep spiritual faith is refreshing Arbery notes with complexity. That their faith is essential to how the moments that looked like they were going downward, instead reversed and moved to a contented and hopeful resolution, makes sense.

Corsicana is at Playwrights Horizons on 42nd Street with one intermission. For tickets and times go to their website: https://www.playwrightshorizons.org/shows/plays/corsicana/

‘Fat Ham’ at The Public Theater, LOL Genius

Pulitzer Prize winning Fat Ham a hybrid genre “tragedy,” “comedy” take-off on William Shakespeare’s Hamlet ingeniously tweaks the concept of the revenge play while upending with quips and double entendres every stereotypic trope and meme of the majestic language of the Bard. James Ijames’ facile and seamless adaptation of the familiar and unfamiliar in one of Shakespeare’s most performed plays reveals his exceptional wit, and gobsmacking sensitivity that is at once a send up of age-old themes, yet a profound exploration of current issues in black culture. Now in its extended NYC premiere at The Public Theater, Fat Ham is a co-production with the National Black Theatre.

Directing with pace and timing to incorporate joy, wackiness, and profound, spellbinding, cutting hurts of father/son, nephew/uncle animus, Saheem Ali knows the inside of Ijames’ book and incorporates the selected cultural music with an appropriate meld in the backyard celebration of Rev and Tedra’s wedding celebration. Immediately, we fall in love with plump Juicy portrayed by Marcel Spears whose every cell is tuned up to inhabit the perspicacious, loving, forbearing and wise, gay, college-age kid who is made dizzy in having to confront the cultural confusion of what it is to be black and gay in the American South, something both his deceased father Pap and Uncle Rev (played exceptionally by the edgy Billy Eugene Jones) find repulsive.

As Juicy and his friend and cousin Tio (the marvelously irreverent Chris Herbie Holland) set up for the party, we discover the backstory as Ijames primes the fountain of humor with one liners, quips and jokes between Juicy who’s decorating and Tio who’s watching porn on his phone. Tio doesn’t skip a beat lusting after Juicy’s hot MILF mama Tedra (the exquisite and outrageous Nikki Crawford) when she comes into the backyard.

Crawford’s Tendra makes her showy, striking, drop-dead, dancer body entrance to ask Juicy for his opinion about which sexy outfit to wear. Clearly, she gets off looking young and attention grabbing and Juicy, her baby, flatters her with what she needs. Obviously, they are close and adore one another; hence the subtle and not-so-subtle Oedipal references to mother/son relationship which Ali further references with Juicy’s change up into a black T-shirt with pink sequined lettered “Mama’s Boy” on the front.

Around this time as Juicy and Tio set up balloons in the backyard of Tedra’s house (superbly detailed with a smoker grill, screen doors to view inside rooms of the house, Astroturf, expansive, wooden deck, etc. designed by Maruti Evans), something weird happens. A red and white checkered tablecloth flies from one end of the yard to the other. Initially, it appears that someone threw the tablecloth, except it is not a projectile, it streams and flutters, zipping speedily and covering enough ground to spook Tio, who recognizes it as a ghost.

Subsequently, under a brown and white table cloth, Juicy’s father Pap speaks out unghostlike, as he throws off the tablecloth humorously and makes his dynamic entrance in a sequined white suit, sporting striking white hair (thanks to Dominique Fawn Hill’s sensational costume design and Earon Chew Healey’s hair and wig design). As ghostly presences go, his is hilarious. Occasionally, the steam from his betwixt and between state of limbo wisps up from his collar, proving his ghostly being is supernatural and otherworldly. The ghostly effects by Skylar Fox’s illusion design are coolly delivered, and sufficient enough to make us believe that Pap is not from the land of the living.

Having a hard time negotiating Pap’s return and his supernatural condition, Juicy quips about his being deceased and surprising as ghosts go, but Pap isn’t having any jokes. He’s furious. He upbraids his son for being “soft,” referencing his disapproval with Juicy’s gay lifestyle in a typical macho Dad infusion of homophobia. Then, Juicy indicts Pap for not liking him or ever being the loving, mature guide a father should be. Indeed, Ijames’ characterizations credit Juicy for shunning his father’s lifestyle and sticking to one that is more wholesome and life affirming, though culturally, not acceptable.

However, as Pap relates why he has returned, the reveal of Pap’s characterization turns on a dime that he is proud of his machismo. We learn that he is an ancestral criminal whose family provoked a crime spree over generations. His ancestors have passed down this legacy of their criminality all the way back to the days of slavery. And having been abused and abusing, in the course of running his barbecue restaurant, Pap murdered and ended up in prison where he, too, was murdered.

Interestingly, the parallel is drawn. If one doesn’t choose criminality to establish one’s identity and manhood as a black man, what choice does one have? Clearly, Pap’s disgust with Juicy’s choice also goes to what he wants Juicy to do for him. Get revenge on his “sainted” brother who had him killed in prison, then move into his bed and life. The only way for Pap to gain revenge is murder. Pap doesn’t see his way clear to changing up the tradition of criminality with his son which would be a greater form of revenge on the culture of racism by not following the stereotypes the racist culture promulgates. But for the cruel and infamous Pap, the sweetest pay back would never be through redemption or ending the cycle of self-destruction prompted by racism. Pap wants an eye for an eye and to reestablish his respect and manhood through his son.

Unfortunately, for Pap, Juicy isn’t a criminal. His hopes and dreams and his identity journeys in a different direction. Thus, Pap’s need for his revenge may be aborted. Juicy must decide what he wants for himself. And part of the first conflict is whether or not Juicy will go through with Pap’s plans or resist them. After all, Pap may not be who he presents himself to be. He may be a devil tempting Juicy to repeat the same old nullifying actions his ancestors have enacted, living lives of misery and gaining an early death. In a fun recapturing of part of the speech Hamlet (Juicy) delivers to Horatio (Tio), Juicy suggests he will test the ghost to divine the truth.

Though it is never mentioned or suggested, in Fat Ham racism is the elephant in the room. Because of it, Pap’s attitudes about Juicy being gay and not being manly close out other choices for his son in Pap’s estimation. The choice for a black man is to be a macho criminal. And only a macho criminal can get a proper revenge and most importantly respect. That Juicy is bucking the stereotype of black men as criminals doesn’t appeal to Pap. That racism has closed off options for Pap so that he would never consider going to college like Juicy is understated. However, as the play progresses, Juicy has choices and will not be held down by Pap’s definitions of manhood, identity and success. Yet, hating his uncle and missing Pap, even though he was mean and cruel, he has to get justice for Pap’s murder. How he does that is the linchpin of this wonderful production.

The beauty of Fat Ham is like Juicy says, sometimes tragedies don’t have to end like tragedies where everyone dies. Ijames jumps back to Shakespearean prose in crucial aspects of the play, including soliloquies about catching the conscience of Rev with a game of charades during the entertainment portion of the down-home celebration. Also, Juicy breaks the fourth wall and confides in the audience. He effectively gestures, rolls his eyes and with superb pacing and timing flicks his fingers in response to silly comments by one or the other of the characters.

Like the other actors, Juicy’s pauses are weighted for a laugh which he and they always get. The innate timing is a function of brilliant performance technique as well as practice and precise shepherding by the director. The laughs come because the actors are authentic and spot-on. I could have stayed and watched another one half hour. I felt engaged and was having such fun with the machinations and carryings on of the characters.

In breaking the fourth wall with direct-address commentary, Marcel Spears is masterful. At the point where he ruminates about how he will trip up Rev and watch for his reactions, at the beginning of the soliloquy, Spears looked at the audience confidentially and said “The Supreme Court is ghetto.” This was Friday evening after a day’s news of the Supreme Court’s decision against Roe. Spears received two full minutes of applause. He waited, then seamlessly segued into his plan to catch Rev. Wonderful at creating a relationship with the audience, by the conclusion we could have gone up and hugged him.

Charismatic, alive his performance was cleverly unassuming. His interactions with his fellow actors’ characters were completely natural and endearing. Considering that he had the most stage time, the pressure was on him to carry the show. There were a few breaks here and there when the spotlight was on others. For example, Chris Herbie Holland’s stoned rhapsody on why you should live to enjoy your life and stop being negative as an out of his mind riff is wonderful. Marvelous, too, is Larry’s transformation from soldier to what he’s wanted to do perhaps his entire life. His friendship with the free-wheeling Juicy allows him to reveal what he is capable of. Calvin Leon Smith knocks his concluding performance out of the park. It makes sense the production ends with him.

Joining the celebration mid way and present for Juicy’s confrontation with his murderer uncle are friends Rabby (Benja Kay Thomas in a wonderful send-up of the religious, strict, black Mama), her daughter Opal (Adrianna Mitchell’s bored, obedient-disobedient Lesbian), and son Larry (Calvin Leon Smith). Their interactions pair up perfectly with Juicy as they discuss their personal lives and break free from parental strictures and manifest their chosen identity. Their interactions provide grist and humor as they unravel their specific characterizations. What is incredibly upbeat about Fat Ham is the roller coaster ride into humor and fun with just enough Shakespeare to make it interesting and memorable.

The second half of the play with the entertainment portion, i.e. Tendra’s searing hot grinding Kareoke, Juicy’s soulful wailing that Rev characteristically puts down and the charades they play that lead to the reveal, all work beautifully and keep the vibrance climbing to the plays explosive climax. How the actors chow down on their barbecue and integrate the song portions into their partying is realized perfectly thanks to their prodigious talent and Ali keeping it as real as possible. Even the corn looked delicious. Importantly, Juicy confronts Rev ‘s murder of his father. What happens after that certainly is karma stepping up to the plate and hitting back.

The themes about truth and honesty being necessary to fight cultural folkways that destroy are the strongest. The performances are riotous, loving and spot-on. The ensemble work is some of the best I’ve seen this year. I can’t recommend Fat Ham enough as one of the finest productions of the season. It has moved from other venues and may go to Broadway. However , if the venue is a smaller house, that might be the best. This play’s greatness is its intimacy that Juicy achieves with the audience as his confidante. It may be lost in a too large venue.

Kudos to the creative team. Not mentioned are Stacey Derosier purposeful lighting (the surreal blue was excellent for enhancing the Ali’s wild staging and character poses. The sound by Mikaal Sulaiman was uniform in each of the songs sung and the supernatural musical elements were eerie. Lisa Kopitsky’s fight direction was realistic. Marcel Spears fall was dramatic and there were gasps from the audience believing Juicy was hurt. Finally, Darrell Grand Moultrie’s choreography was exuberant and for the concluding number hysterical.

Fat Ham is extended to 17th of July. For tickets and times for this must-see production, go to their website. https://publictheater.org/productions/season/2122/fat-ham/ I just loved it!

‘The Bedwetter’ a Hysterical and Meaningful Sarah Silverman Romp

Sarah Silverman is a legendary comic and she may have been born with a funny bone. But how did she morph into the talented comedian who has a musical production about her early life, playing eight times a week at the Atlantic Theater Company? We discover the inspirations that planted the seeds of comedic success in the very humorous, irreverent pop music show The Bedwetter. Based on Silverman’s memoir The Bedwetter: Stories of Courage, Redemption, and Pee, the theater adaptation highlights the most important year of Sarah Silverman’s life, a year that intimated the possible future success Silverman would offer in her unique comic grist.

With book by Joshua Harmon and Sarah Silverman, lyrics by Adam Schlesinger and Sarah Silverman, music by Adam Schlesinger, choreographed by Byron Easley with creative consultation by David Yazbek, The Bedwetter is a hoot. Also, it is ironically woven with themes about divorce, mental illness, childhood angst and dysfunctional families. The two act musical briskly unfolds via the comical and exuberant perspective of precocious, potty-mouth Sarah played by the uber talented and sharply focused Zoe Glick.

Glick is a wunderkind. Her pacing, nasal singing voice and edgy delivery reveal she is a natural. She portrays Sarah as a loving, exhausting, “in-your-face, quick-witted love bug who goes through a series of disastrous events at the worst time in her life. The momentous problems occur at the formative age of ten-years-old when she has to go through her parent’s divorce, her mother’s increasing depression, her father’s philandering with most of the moms in town, and a move which forces her to attend a different middle school where she has no friends.

Though she manages to face these cataclysms with the help of her alcoholic Nana played by the inimitable Bebe Neuwirth in a wonderful turn, there is one issue which is insurmountable. She is a bedwetter. The secret remains among family and perhaps former friends, however, it cramps her style with making new acquaintances. Not only is she embarrassed because she is “too old” to wet the bed, her terrible debility infantalizes her. Thus, she feels inferior and demeaned by a condition she can’t control. The opening number (which also closes the show in a beautifully made sandwich) “Betterwetter” encapsulates all of her issues. Glick sings it with zing, verve and joy.

Interestingly, wetting the bed at her age, we note, must be related to her parents’ divorce, the move and inner stress. And then we discover that it is genetic. Her father Donald (the humorous Darren Goldstein who rocks many women’s boats) also wet the bed. However, as he enjoys reminding her, he did grow out of it. Sarah wonders when that wonderful occasion will happen in her life to end the emotionally painful stigma.

As we follow Sarah who introduces us to her family, we meet her sister Laura (Emily Zimmerman) who disowns her in school and puts up with her at home, decrying she doesn’t know who she is and how she is a part of the family. Interestingly, in Act II, Laura’s approach changes after Sarah’s life takes nullifying downturn. And when Nana has to be hospitalized, the Laura softens her attitude toward Sarah. Then the sisters unite and become close again. As Laura, Emily Zimmerman works the transformation from annoyances to hypocrisies to fear and concern for Sarah in a fine and authentic acting and singing performance.

Sarah’s mother Beth Ann, normally portrayed by Caissie Levy covered by Lauren Marcus the night I saw the production is only capable of staying in bed and watching television. We learn why this situation abides in the second act when a fight erupts between Beth Ann and Nana and the truth spills out. It is then we understand Beth Ann’s depression and feel empathy for her. However, Nana ends up becoming sick over the remembrance of what happened. Indeed, her hospital stay reveals self-punishment and feelings of guilt for she feels responsible for events that cause Beth Anns’ depression.

Considering the circumstances of her caved-in life, Beth Ann does the best she can. She is aware of Donald’s philandering, one cause for the divorce. However, he is a good father. He provides enough money to take care of the family and eventually pay for Sarah’s treatments to stop her bedwetting. Also, he is there for his two daughters. Likewise, though Beth Ann’s debilitating depression hinders her for “normal” activities, she stands by her children and when Sarah needs her most, she is present for her.

Initially, Sarah, encouraged by Nana (Bebe Neuwirth comes prepared with an authentic accent and bright, cheerful demeanor) who tells her she can do anything, coasts into school. We are impressed as Sarah’s humor and agreeability eventually lures the girls in her classes to be her friends, rendered in an adorable song with Charlotte Elizabeth Curtis (Ally) Charlotte MacLeod (Abby) and Margot Weintraub (Amy).

Mrs. Dembo their teacher (the very funny Ellyn Marie Marsh) tries to inspire them to hone their talent like Mrs. New Hampshire did (the lovely voiced, effervescent and funny Ashley Blanchet) for their school is presenting a talent show. Sarah and her friends begin to practice songs for the show, inspired by the golden tones of Mrs. New Hampshire. When they practice together, they are crackerjack astounding with their harmonies and seriousness in “getting the number right.” They should form a girl band.

After Sarah invites her new friends to her Dad’s house, they are impressed. Darren Goldstein’s philanderer number as Donald brought the house down when I saw the show. The men loved his machismo, which he manages in the ethos of a hapless idiot far from a hot, “know-it-all” arrogant lothario. His balance in achieving a hysterical, irreverent unpolitically correct and refreshing tone is well shepherded by director Anne Kauffman.

The ease that Donald presents with Sarah and her friends opens a door of hospitality so that Sarah is invited to a sleep over. She almost doesn’t go because she will wet the bed and the girls use the occasion to add to her horrific embarrassment. But her mother unthinkingly tells her she’ll be OK. Meanwhile, Donald tries to find cures for Sarah which result in a very funny bit between the hypnotist portrayed by Rick Crom who is brilliant and whose voice is excellent for the role. Unfortunately, the hypnosis doesn’t work and the hypnotist sings a counterpoint duet with Sarah underscoring that he’s a fraud as she sings that the hypnosis doesn’t work.

When Sarah goes to the sleepover, she has an accident. What happens after this event reaches into catastrophe. However, Silverman’s horrors come with great humor and irony. The number that takes place in the psychiatrists office is farcical in a great way, for the doctor (Crom) sings the praises of the latest cure for depression, the diagnosis he gives Sarah. As the doctor Crom leads the large dancing yellow Xanaxes that come alive to sing along with him about their wonderous effects. Crom attests to their ebullience as he flutters and skips high as a kite on Xanax. The number is one of the best in the show, as well as the most sardonic. Just great!

As the good doctor and singing dancing Xanaxes move off stage, Sarah desperate to do anything to stop her debility pops her pills for “depression.” We shudder understanding that Sarah is too young to take such powerful drugs, but it is a fact that Big Pharma likes to get folks hooked as young as possible. Instead of stemming her depression, anxiety and sorrow, Sarah joins her mom in bed where together the sing of their troubles and their hopes.

Ironically, the depression that Xanax is supposed to cure throws her into a full-blown depression so she must take more to attempt some relief. Once again, the cure is worse than the condition. The resolution does arrive to reveal the need for redemption for the family and salvation for Sarah who is still wetting the bed.

The deus ex machina (a seemingly unsolvable problem in a story is suddenly and abruptly resolved by an unexpected and unlikely occurrence) arrives when Miss New Hampshire appears in a dream. She tells Sarah about her secret which brings the child confidence in knowing that this lovely, talented woman had the same problem. Maybe there is hope for her after all. By the conclusion of this wacky and warm musical, Sarah takes the stage in the talent show and cracks open her wild and authentic comedy number (which we’ve been watching). The show ends with the rousing song “The Bedwetter” sung by the cast, and our delectable farce sandwich concludes.

The production is excellent, though it is “dirty” and “uncouth” and unpolitically correct and indecent for younger girls (that’s for the NEWSPEAK thought police on “the left” and “the right,” reference to 1984 by George Orwell). Anne Kauffman has rehearsed the cast to a fine rhythmic pace, rapid fire delivery of quips and jokes and acute pauses for timing which add to the overall hilarity and upbeat performances.

Nevertheless, when the show turns to the dark side, all of the issues break wide open and we can empathize with what this family has gone through to make it to the next day. Of course the struggles and strains provide the foundation for Silverman’s comedy and engender her growing up beyond her years, sustained by cracking jokes to forestall the misery. Indeed, misery and humiliation provide the meat upon which Thalia, the muse of comedy feeds. Silverman and Thalia are besties in this production. And Silverman’s and Harmon’s and Schlesinger’s book and lyrics inspired by the immortal acquaint us, the actors and director with her finer points of merriment.

The cast works seamlessly as an ensemble. Their voices are powerfully resonant and spot-on. Each of the leads remains precisely authentic in their own songs, whose lyrics are humorous, sometimes wildly hysterical, but always pealing out the human condition.

Kudos to the set design which was functional, variable and effectively minimalistic (Laura Jellinek). Costumes by Kaye Voyce showed up the Ad dancers and Miss New Hampshire well. Japhy Weideman’s lighting, Kai Harada’s sound, Lucy Mackinnon’s projections, Kate Wilson’s dialects made the production’s themes cohere. The music team is exceptional. These include: Dean Sharenow (music supervisor & coordinator) Henry Aronson (music director) and David Chase (orchestrations).

This is one to see for its exuberance, fun, laughter and poignant moments, too rendered by the fine performances of the ensemble and sensitive, balanced direction, keeping the humor in the pathos. For tickets and times to The Bedwetter that runs about two hours go to their website: https://atlantictheater.org/production/the-bedwetter/

‘Golden Shield’ at MTC, Review of a Must-See Production

Golden Shield by Anchuli Felicia King, directed by May Adrales currently at Manhattan Theatre Club is a thematically rich and profound work that looks into corporate greed, political activism, digital censorship as a means of control, the ethic of understanding a different language through translation without considering cultural variance, and relationship reconciliation redux. Through the lens of a jury trial against corrupt actors who refuse to consider the consequences of their actions when digital efficiency and progress is at stake, King examines ethical responsibility and the fallout when accountability is measured in litigation awards.

The principal theme begins when audience members hear the instructions to keep masks on and turn off cell phones in another language. Mandarin. They think they know what is being discussed because it is the protocol of all theatrical experience in New York City to be reminded before the play begins to be the dutiful audience. However, in reality, unless they have a working knowledge of Mandarin, they don’t know what is being said. The speaker might be cursing out the audience; thus, the setting and context determine the level of trust the audience has for the speaker.

This is the linchpin of Golden Shield, illustrated by Fang Du, the clever and affable Translator who takes our hand during the more opaque sections of the two act drama and guides us with his knowledge of Mandarin and unaccented English. We can only assume that he understands both languages to provide a correct translation of what is happening when the conversation is only in Mandarin. Thus, we trust him. But should we? This is a slippery slope. Indeed, trust between and among human beings, even if they are friends and family, as King proves, is flawed.

It is a fluid theme. By the end of the play, The Translator learns an important lesson. There is no correct translation for what happens during the play between older sister Julie Chen (the excellent Cindy Cheung) and younger sister Eva (the superb Ruibo Qian) who Julie abandoned to live with their tyrannical mother in China when she was a child. Nor is there a correct translation for what happens to Li Dao (Michael C. Liu in a heartfelt powerful portrayal) when Eva gives a one sentence translation that mistakenly encourages Li Dao to take a course of action that impacts him and the case that Julie is trying for her law firm.

Indeed, The Translator and the Chens realize that translation is a matter of interpretation of cultural values, the proper selection of metaphors and figurative language, subtle inflections and nuances in a contextual medium that must be included to convey what an individual is saying. Finally, there is no translation for why Chen acts as she does at the play’s end, nor is there a translation for the villain ONYS Systems in how they relate to the Chinese government.

Language between native speakers is not easily conveyed if there are geographical and cultural differences within a nation. Words hold loaded meanings and what one thinks one communicates may hold offense or have an entirely different understanding for the listener. How much more is the confusion of communication if a language that conveys meaning in a circular fashion through characters and pictorial thoughts is translated to a listener and speaker of English which is essentially linear and word based, and whose time is chronological? Mandarin, Cantonese, Korean, Japanese are effectively without chronology, and retain a circularity and pictorial, visual thought process seamlessly navigated and understood by those who speak, read and write it.

Interestingly, Fang Du’s Translator warns us about the chronological expansiveness of English compared to the circularity of Mandarin and suggests there is no word for word translation. However, by the end of the play as he lives through and guides us through the events, even he is caught up short. The revelation for him is profound because he has been in the “God” seat. But he becomes enlightened like the Chens and the audience that what results is because of incomplete translation and incorrect “interpretation” and felt understanding. Mistaken understanding roils through every interaction in King’s play; it is fascinating.

This is perhaps the most profound of the themes in King’s work which takes place between 2006-2016 and shifts scenes from Washington, D.C. to Beijing, to Yingcheng, to Dallas, to Palo Alto to Melbourne. Though flashback is used and The Translator keeps us mapped out in the setting and scenes, Act 1 is top heavy. The playwright wants to say so much that she dilutes the force by trying to jam pack it all i>. Truly, the play could be streamlined and the dialogue shaved at the least to arrive at the question what are the most salient, striking themes. How can they be made to bring the audience toward vibrance.

When I saw Golden Shield, members of the audience appeared to be most affected by the relationship which implodes between the Chens. Nevertheless, King’s passion for the topics and themes is noteworthy. How do you streamline even a few words when you are in love with what your characters are saying to you. I get it, but it bears looking at for future productions to make Act I a dynamo and powerhouse leading through Act II in its explosion/implosion and powerful trial scene testimony then the conclusion.

The frame of King’s work fans out into part courtroom drama, part lawyer discussion, part insider talk at the fictional American tech company ONYS Systems. They get the contract to create a process to help them spy on any activity that opposition and adversaries use to smash the firewall of digital censorship that pertains throughout China. ONYS Systems’ pompous Elon Musk-type executive Marshall McLaren (the sardonic and superb Max Gordon Moore) creates an effective firewall by decentralizing it into multiple checkpoints, making it much easier for Chinese monitors to gauge spying and identify hackers who defy China’s digital control.

Thus, ONYS Systems in an extraordinary pro-communist political move is used as a tool of the Communist Chinese government to expose potential American spies in a counter-American action to protect itself. It also is used as the chief deterrent to stop hacking their firewall by identifying the hackers and punishing them severely.

During the course of the play, we understand the culpability of ONYS Systems through Moore’s McLaren. His nonchalance and self-satisfied genius, that he and he alone came up with this plan of decentralization for his company which increased their profitability exponentially as China pays them a huge price is loathsome. Interestingly, Moore makes the character ironic with the help of Adrales fine direction. Thus, the full understanding becomes “lost in translation.” And the full impact of how China has created a puppet in McLaren/ONYS Systems as a compromat or whatever the Mandarin word is for those without ethics or integrity who turn against their own nation, humanity and the “little people” for extraordinary wealth is muted. But hey, what the hell; it’s just business. (Some of this plays out from real life; check out Cisco and Yahoo litigation.)

Meanwhile, McLaren and ONYS Systems have ignored the impact of this “Golden Shield.” Their bottom line is paramount. Enter Chinese-American attorney Julie Chen who leads a class-action lawsuit by eight dissidents against ONYS Systems, chief among them the severely injured Professor Li Dao. Chen has found an obscure law used against pirates a few centuries ago that gives federal courts the jurisdiction to hear litigation filed by non-U.S. citizens for torts committed in violation of international law. She convinces her partner in the firm (Daniel Jenkins who doubles in his ONYS Systems’ role ) that they must take the case of the dissidents. She is passionate, convinced that McClaren and ONYS Systems are culpable for injuring the dissidents via their digital assistance to the oppressive and brutal Communists. Indeed, during various flashbacks we learn of Professor Dao’s five year imprisonment and torture because he showed students how to circumvent the Communist governments’ new “Great Wall of China,” The Golden Shield.

Enter the side plot and conflict between the siblings which also is lost in translation, misunderstanding and flawed communication because of emotional trauma, cultural differences and denial. Julie hires her sister Eva to visit China with her and speak to Professor Liu who can only testify and reveal so much of the brutality visited upon him under the Communists because he has been traumatized. The most vital scenes of the play occur with Li Dao and his wife Hang Mei (the fine Kristen Hung). Liu represents Li Dao with such empathy throughout that his portrayal ironically, though we don’t understand his speech, conveys superb understanding of his feelings and his expressions. Thus, the theme of translation being an incomplete and flawed means of communication hits the hardest with their performances because the words don’t matter. The emotions, tone, timbre wrought with great feeling immediately convey truth.

In Act II the courtroom scene where Professor Dao testifies is sensationally done with all the actors firing on all syllables. However, Chen as a result of her own trauma with her mother and leaving her sister in China has a confluence of emotions which end up forcing her to take a path which is devastating. For her part Eva, who we find out has been a sex worker and has compromised her sister’s relationship with her law firm partner, ends up bereft and lost. By the conclusion all the characters reveal that the events have traumatized them in one way or another. It doesn’t become a matter of winning or losing the lawsuit, it becomes whether or not one respects oneself for one’s choices.

Only Eva in her relationship with her Aussie lover (Gillian Saker who also does double duty as lawyer for ONYS Systems) seems to be seeking some sort of resolution with herself, especially after she throws over her sister Julie. But all of the characters are flawed, not very appealing, ethically challenged with the exception of the Professor Dao who has paid a terrible price for challenging China’s autocracy and repression. And indeed, by the play’s conclusion the future appears even more bleak as McLaren provides himself an off-ramp from changing his ways reflecting on the Dark Web, Block Chain and other tech “innovations” which provide myriad ways toward profitability by any means necessary.

I particularly enjoyed dots’ scenic design which coupled with Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew’s lighting design was used to smashing effect during the scenes relating to the Professor’s prison term and punishment. The set of Li Dao’s and Huang Mei’s living raised on a platform and framed by the lattacework partitions/screens on either side intimated the cultural setting, though the living room appeared Western. Its functionality was pointed and well thought out. Kudos to the rest of the creative team for applying King’s themes and Adrales’ vision. These include Sara Ryung Clement (costume design) Charles Coes and Nathan A. Roberts (original music & sound design) Tom Watson (hair & wig design).

The show closes on Sunday 12 June. I have highly recommended to to friends. It is a must-see and will be performed again. Look for it regionally. For tickets go to their website: https://www.manhattantheatreclub.com/shows/2021-22-season/golden-shield/

‘Mr. Saturday Night,’ Billy Crystal, David Paymer, Dazzle With Comedic Genius and Heart

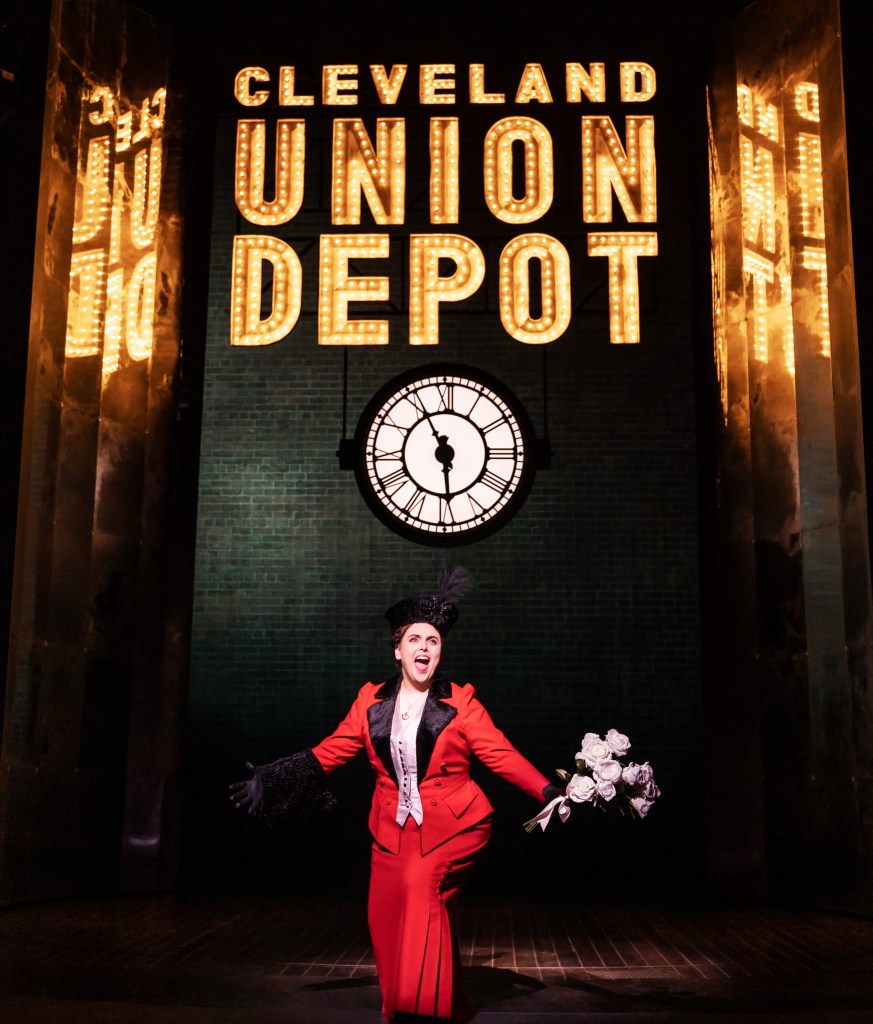

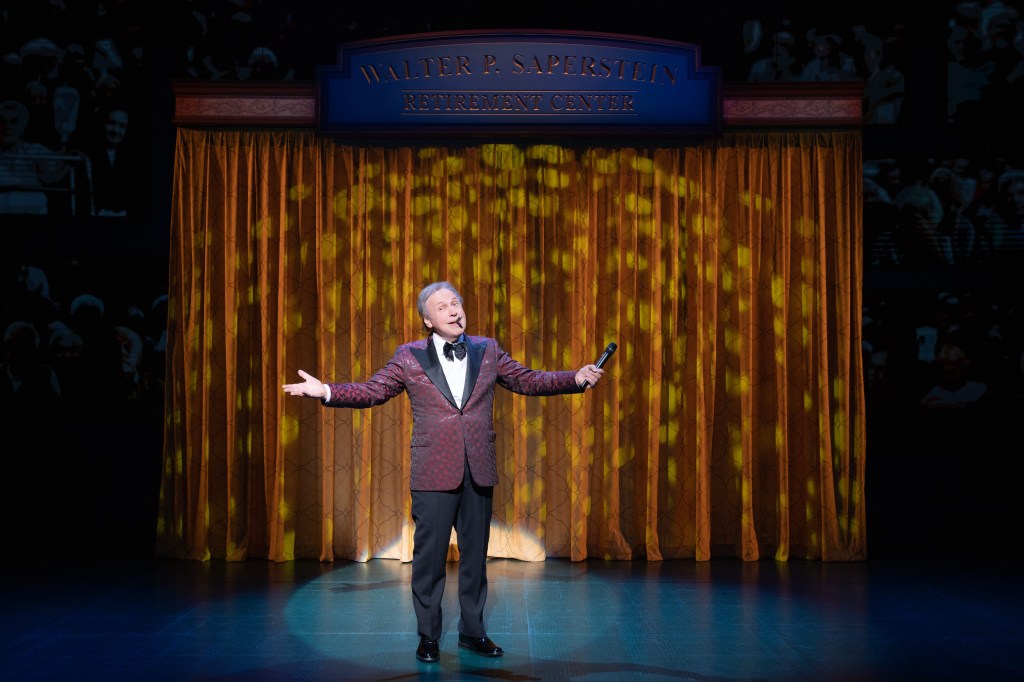

Billy Crystal’s reshaped Mr. Saturday Night at the Nederlander Theatre, directed with acute sensitivity by John Rando is based on Crystal’s 1991 Oscar nominated titular film. This production “hurts!” (in today’s parlance “kills:). Crystal embodies “Mr. Saturday Night” from head to toe. In the two act musical Buddy Young, Jr. (Crystal) luckily faces the opportunity of a second chance in his waning comedian years. With this do over, he gets to reexamine how he sabotaged his career with the hope of regenerating it. Most importantly, he faces the opportunity to revitalize his estranged relationship with his brother Stan (David Paymer reprises his Oscar nominated film role) and his non existent relationship with daughter Susan (the golden voiced and superb Shoshana Bean).

We all love second chances because we need so many of them. Buddy is no exception as the writers fashion his character to bump up against chance after chance. Indeed, in flashbacks from present to past to present, we note that as Buddy’s ego explodes with his successes, he eventually blows every chance that comes his way. When it is announced that he has died on TV (a symbolic reaffirmation of hope for a resurrection) Buddy plunges into the opportunity with the help of agent Annie Wells (Chasten Harmon covered by Tatiana Weschsler the night I saw the musical). The dramatic problem arises. Perhaps Buddy has gained the wisdom to retrieve the lost golden ring of success and once more establish himself. But what if he hasn’t?

This caveat is the crux of the conflict and arc of development. Can Buddy get out of his own way long enough to be the best human being he can be, absolving himself of past regrets with humility and aplomb? You’ll just have to see this reconfigured Mr. Saturday Night to find out

Crystal, himself is receiving a new thrust of fame in this upward moving transition in his career as a Broadway star going for his second Tony Award. He won a special Tony for 700 Sundays) doing what he enjoys, performing in front of a live audience every night. The production, despite a few twitches, is an absolute joy to see, and Crystal is the ebullient muse of hilarity, pattering jokes with lightening speed and seamless grace.

Reprising his role with Paymer, Crystal is the former Borscht Belt comedian, who once had a successful TV show until he didn’t. Paymer is his long suffering brother/manager/agent who was generous with his own salary during their heyday, but barely has enough to treat his girlfriend to a pricey dinner. Randy Graff does a fine job as wife Elaine, encouraging Bean’s Susan to “give her father a break.” “Putting up with her father is something Susan finally shutters with maturity and firmness, prompting Buddy to reassess, reevaluate and recalibrate or lose her love. The scene between Bean and Crystal against the warm background of the projections of the NYC brownstones and the doorway to Susan’s apartment and new relationship with her Dad is beautifully done.

The production combines an endearing and poignant update with LOL vibrance. It soars with Crystal’s outstanding performance where he sings and dances, as one would expect seventy-something Buddy Young, Jr. to crow out a tune and jubilantly hop and skip some mildly energetic dance steps, sans flips, strenuous tap or break dancing. Indeed, Paymer and Crystal deliver their enjoyment “I Still Got It,” and companionship together and also dig deep when their characters hit the abyss: Paymer in the exceptional “Broken,” and Crystal in the profound “Any Man But Me.” Surprising, endearing, adorable, belly-laughing, fun, thoughtful and appealing, the principals are a team and appear to have fun making the audience laugh in a time when we desperately need to apolitically chortle and “fall out” in a life-affirming way.

With Book by Billy Crystal, Lowell Ganz and Babaloo Mandel, Music by Jason Robert Brown and Lyrics by Amanda Green, the production has been nominated for five 2022 Tonys, including Best Musical, Book, Score (Brown and Green), Leading Actor in a Musical (Crystal), and Featured Actress in a Musical (Bean). What is marvelously stranger than fiction is that the film, if one reads the “critics” was not “the bomb,” it did not “kill” and it did not, in Buddy’s words “hurt them.” It flopped. Crystal and his creative team are to be credited for courage and gumption to try again, this time as a Broadway musical, one of the most difficult of creations and during an ongoing pandemic that no one likes to acknowledge.

However, this is Mr. Saturday Night’s persevering second chance. With the added lift of the music and dance, and overall nostalgic silliness of 50s TV bits, where actors dress in hot dog costumes, cigarette boxes, etc., (Jordan Gelber, Brian Gonzales, Mylinda Hull) Mr. Saturday Night offers a retrospective on a history younger audiences don’t know. Also, it is an encomium to comedians who were huge greats in their time, some of whose stars still shine in films on Turner Classic Movies and black and white TV reruns.

The musical also highlights the importance of the Borscht Belt circuit in the Catskills, where comedians and entertainers could credibly try out their material and look for opportunities like Buddy did when he “covered” for Milton Berle at Farber’s. As the musical flashes back to Buddy, Stan and Elaine as twenty-somethings, we discover it is at Farber’s that he lands the gig that launches his successful career and Stan’s as agent and manager. The flashback also reveals how he met Elaine (Graff manages to be a convincing younger version of Elaine) whom he unwittingly “stole” from Stan in a a sour note between the brothers. Thus, the characterization and arc of development eventually reveal head on undercurrents of the strife between Crystal’s Buddy and Paymer’s Stan as a loop of pain which the actors convincingly inhabit and play battling each other.

All these events with his brother, long suffering wife and broken-hearted but defiant daughter reveal the depth of the characters. They also illuminate reasons for Buddy’s self-torment, ambition and feelings of inferiority all of which are the fountain of his comedy which is part insult comedy, part ironic defense, and the type of ridicule which makes angels laugh. But when it’s directed at the individual in question, it hurts for real as dismissive one upmanship. Buddy has a tough time differentiating Shakespeare’s, “All the world’s a stage,” and is continually making his entrance and never pausing long enough to realize he needs to exit.

In an important scene with agent neophyte Annie (the fine Wechsler), Crystal’s Buddy gets to praise his comedy mentors. We note on the walls of the Friar’s Club and in projections a wide expanse of brilliant funny men and a few women of high humor. Buddy’s rant implies Annie should know the greats and this inspires her to do her research, then work like the devil to help Buddy get something which turns out to finally land as a part in a film. The role is funny and incredibly poignant and it requires Buddy audition, which he does. But after all the angst rehearsing and auditioning and blowing a chance at closeness with his daughter, his “big opportunity” is destroyed when the role is given to Walter Matthau. Bummer. Crystal handles this earth shattering moment with an ethos that’s believable Buddy. What he’s lost isn’t recoverable, for the loss isn’t just this part, its his mountainous history of regrets.

Unlike the film which referenced the comedian’s waning years from a younger man’s perspective (Crystal was in his forties, ironically “old” at that time), this Mr. Saturday Night shines in the age appropriate sequences. Interestingly, it is their younger portrayals by Paymer and Crystal as the twenty-somethings, that seem a stretch with wigs (Charles G. Lapointe) and make-up that don’t quite cohere.

However, when the flashback to Farber’s arrives, we’ve been prepped with jokes by the opening number “We’re Live” (Jordan Gelber, Brian Gonzales, Mylinda Hull). Then Buddy does his act at a retirement home (“A Little Joy”), which is a laugh riot. And by then, we’ve become acquainted with the premise, the announcement of Buddy’s death on TV, and his “new lease on his career” as agent Susan-Tatiana Wechsler sings “There’s a Chance, ” and excited Buddy and Stan sing and move to “I still Got It.” So, what’s a bad hair day for the two men returning to their younger days measured against the overall success of the well paced Act I that moves even more briskly through Act II and the conclusion after which Crystal takes a few audience questions? Well…(said with an upward lilt of a Jewish accent).

The themes of aging and regrets not answered, second, third and fourth chances, familial reconciliation, and redemption even for the incorrigible, spin in and out with a bow and a wink, superbly subtle. The sets of Buddy and Elaine’s home, Faber’s, the paneled Friar’s Club and the old time TV Studio designed by Scott Pask are spot-on, as is the costume design by Paul Tazewell & Sky Switser enhanced by Kenneth Posner’s lighting design and Kai Harada’s superb sound design. The Video & Projection Design is smashing, reminiscent of divided screens from the period, creating various effects pegged to the emotion of the scene.

The choreography by Ellenore Scott is just enough for this type of show and the actors are at ease and comfortable with their steps and movement. As silly as Elaine’s wishful thinking about leaving for “Tahiti” is, Graff pulls it off looking debonair and adorable. Thanks to Jason Robert Brown’s Arrangements and Orchestrations, David O’s Music Direction and Kristy Norter’s Music Coordination, the tone and tenor of the music fits with the book by Crystal, Ganz and Mandel, with Green’s lyrics. The time, effort and love shows, as all is held together by John Rando’s direction. Wow!

Get your tickets to this must-see show. You are not going to see this production with this cast again. For tickets and times go to their website: https://mrsaturdaynightonbroadway.com/

‘Belfast Girls,’ a Powerful, Shining Work at the Irish Repertory Theatre