Blog Archives

Laurie Metcalf is Amazing in ‘Little Bear Ridge Road’

On 12 acres of property in Idaho on the top of the ridge, the sky is so intense it makes Ethan (Micah Stock) panicky because he feels that his life is insignificant against the vastness of the galaxy glittering before him. Sarah (Laurie Metcalf), Ethan’s aunt who owns the property and appreciates the nighttime view tells him she “thought once about buying a telescope, but you know. Then I’d own a telescope.” The audience laughter responding to Metcalf’s pointed, identifying statement that reveals her edgy, funny character peppers Samuel D. Hunter’s powerful, sardonic Little Bear Ridge Road currently at the Booth Theatre.

Metcalf is terrific as Sarah who delivers comments like darts hitting the bullseye and evoking laughter because her words are heavy with authenticity. Her statements convey meaning and pointedly eschew the gentility of polite conversation. Micah, Sarah’s nephew, is withdrawn, remote and masked, not only because the play begins during the COVID-19 pandemic, but because he wears his soul damage on the exterior with a covering of silence that withholds speech. Interestingly, these two estranged family members, one a nurse who doesn’t even nurture her own wounds, and the other, a self-damaged young man of thirty, who can’t really get out of his own way, eventually get along,

With this Broadway debut Hunter (The Whale, A Bright New Boise) weaves a poignant, humorous, fascinating dynamic. Metcalf and Stock inhabit these individuals with humanity and a fullness of life that is breathtaking.

Directed crisply with excellent pace and verve by Joe Mantello, Hunter’s comedic drama that premiered at Steppenwolf Theater Company, confronts human isolation and failed familial relationships. Hunter presents individuals who confuse self-supporting independence with misguided self-reliance. With spare, concise dialogue the playwright explores how Metcalf’s Sarah and Stock’s Ethan rekindle their sensitivity and open up while nursing their fractured, self-victimized souls, to help each other without acknowledging it as help.

Finally, Hunter’s dialogue has flourishes of well-placed poetic grace and rhythm. Within its meta-themes about human beings struggles with themselves, it’s also about knowing when to let go to encourage another’s growth.

Aunt Sarah and nephew Ethan have an ersatz reunion, when Ethan’s father, Sarah’s brother, dies and leaves the nearby house and estate to Ethan to dispose of. Estranged from his father and from her for a number of years, Ethan, who is gay, lived in Seattle with a partner, who emotionally abused him and self-medicated with a cocaine habit. Eventually, they split. Graduating from university with an M.F.A. in writing, Ethan has drifted, stunned by his devastating childhood where he was raised by an addict father, since Ethan’s mother abandoned the family when he was little. How does Ethan learn not to duplicate his problematic relationship with his father, with love relationships with other older men?

For her part Sarah remained in Idaho near where she was born and worked as a nurse during and after her husband left her. Fortunately or unfortunately, they had no children. This means that she and Ethan are the only Fernsbys left on the planet, dooming their family line to extinction, which according to Ethan seems pathetic. Selling her home in Moscow, Sarah tells Ethan she moved to a more remote area because “It suits me better. Not being around—people.”

With her prickly, self-reliance and proud stance refusing help, Sarah has taken care of her house and property, worked, organized documents and paperwork for Leon (Ethan’s dad, her brother). She generously gave Leon money to help him with his bills. When Ethan affirms that was a bad idea because his addict father used it for his meth habit, Sarah states she doesn’t know what he used it for. After all, Leon told her that he never did meth in front of Ethan. The truth lies elsewhere.

As the pandemic passes and circumstances improve, the relationship between aunt and nephew also improves. They communicate more intimately. They watch a TV series and comment about the characters. The dialogue is funny and Sarah and Ethan become family. Assumptions and mistaken views are dismissed and overturned. Realistic expectations fill in the gaps. A surprise occurs when Ethan meets and forms an attachment with James (the excellent John Drea).

Hunter uses James as a catalyst, who provokes a turning point to continue the forward momentum of the play. James comes from a more privileged, loving background and is studying at a nearby university to be a star-gazer for real, an astrophysicist. With eloquence James explains the magnificence of Orion’s Belt to Ethan, as it relates to our sun. Sarah welcomes him and encourages his relationship with Ethan, until once more circumstances gyrate in another direction, all perfectly unfolding with the emotion of the characters.

Mantello arranges the interlocking dynamic among Sarah, Ethan and then James, center stage on a “couch in a void.” From there the characters converse, sit, enter and leave stage right (to an invisible kitchen), stage left (to bedrooms). The recliner couch on a turntable platform in different positions establishes the passage of time between 2020 and 2022. Scott Pask’s set and the lighting by Heather Gilbert are symbolic and interpretive. Our focus becomes the characters and the actors’ exceptional portrayals as they struggle to find a home with each other and themselves, until the threads of grace in their alignment come to a necessary end.

After all, the Fernsbys have to have a legacy, if not in offspring, then in words. And the respite and connections they find together talking and watching TV on a “couch in void” becomes the place where Ethan’s legacy in writing is born, and the Fernbys legacy prevails.

Little Bear Ridge Road runs 1 hour 35 minutes with no intermission at the Booth Theater through February 15th littlebearridgeroad.com.

‘Grey House,’ a Subtle Send-up of Horror Films, That Delivers With Humor and Surprise, Starring the Fabulous Laurie Metcalf

Top shelf performances and eerie effects in lighting, sound, and on-point set design carry Levi Holloway’s horror-thriller Grey House through to its unreasoned, macabre and opaque ending, leaving the audience disturbed and unsettled in an unusual, visceral entertainment. The production, currently running at the Lyceum Theatre until September 3rd, is insightfully directed by Joe Mantello for maximum preternatural weirdness and warped grotesqueness that is also a send-up of the genre.

With sardonic humor and glimpses of the supernatural which evanesce in the twinkling of an eye, the playwright Levi Holloway shrouds the action along a path of darkness, confusion and sometime shock, until the widening road dead ends in a climax and (spoiler-alert) Max’s partner Henry vanishes, replaced by a new guest as Raleigh (Laurie Metcalf), bags packed, leaves.

Spoiler alert! Stop reading if you want to be surprised by the play. Read the rest if you are looking for clues to guide you down the dark road of Grey House.

Where and how Henry de-materializes doesn’t matter. We have witnessed his sadistic torture by a child tormentor and watched astounded at his masochistic enjoyment of pain. When he contributes his substance to create a palliative “alcoholic” drink that anesthetizes, most probably for a future unrepentant male, our fog of understanding clears a bit. Henry receives well-deserved punishment for his unspeakable past acts, that, until he entered Grey House, have gone unanswered. Is the function of this house and these female inhabitants to deliver justice? If so, married couple Max (Tatiana Maslany) and Henry (Paul Sparks) who seek help at Grey House after a car accident are “innocents” walking into a trap.

The creaking, groaning, hellish, two-story, ramshackle abode in the mountains, referred to as “Grey House,” initially appears to Max and Henry as a welcome, cozy shelter from the blizzard and their injuries. However, we know better and not just because of the advertising campaign for the show.

Previously, we have been introduced to the strange, uncanny children of the mountain cabin and their mother/caretaker Raleigh (the sensational Laurie Metcalf). Two of the “sisters” initially raise the spirits in a representative song of the region, singing a cappella. They produce an effect which is haunting and spooky. At turning points throughout the production, a total of four songs are sung: two authored by Mountain Man and the others by Bobby Gentry and Sylvan Esso. Each song is more compelling and meaningful in relation to the action, thanks to Or Matias (music supervisor and a cappella arranger).

Henry’s ironic comment that he’s seen this movie before and they “won’t make it,” lands with humor, horror and truth. We know something he doesn’t. He and Max must stay away from the two unnatural malevolents, a Wednesday Addams meme, Marlow, and her frightful companion in wickedness, the vicious, hell-bound Squirrel. In the initial moments of dialogue and action, they are daunting.

Throughout the action, both could double cast as witches in their sarcasm, sinister intentions and sub rosa text delivered in a straight-forward manner, as they allow the “words to convey the meanings.” The import of their statements are clues to what is really going on, however, the substance is easily missed because the audience is Holloway’s prey and is misdirected as she steers them down the road, and blinds them with her dark shadows of uncertainty.

Nothing is directly expressed. Of course, Henry and Max have the bulk of their interactions with these vixens, who rule the roost and who, Raleigh, their ersatz mom, calls “willful creatures,” an understatement.

As the Wednesday Adams meme who is a self-satisfied, self-admitted, proud “bitch” in the MAGA vein of “owning the libs,” Sophia Anne Caruso is terrific at suggesting the horror underneath the action. She enjoys making her guests, especially Max, feel creeped out.

Squirrel, whose damaging persona is represented by her name and her having chewed the phone chord so no calls come in or go out, is the youngest. Portrayed with insinuation and sadism in a nuanced performance of softness and brutality, Colby Kipnes is superb. She is the youthful doppleganger of The Ancient (Cyndi Coyne) and is the instrument of revenge holding “everyman” predator Hank to account in a twisted time reversal. For unspeakable acts he committed decades before, the young Squirrel and the others collaborate in effecting physical retribution which the anesthetized Henry willingly accepts as his due.

“Grey House” exists beyond time and place, the repository of the wounded in life who exist when we meet them as otherworldly beings or some other undetermined construct of humanity, which the playwright ironically leaves in the realm of uncertainty. When we meet this particular brood, Raleigh suggests others will come and go, as she in fact leaves at the conclusion with a packed suitcase, letting Max who may be a younger version of herself replace her as the caretaker.

The bottles of “moonshine” the ersatz family of women, including A1656 (the fine Alyssa Emily Marvin), and hearing-impaired Bernie (Millicent Simmonds passionately completes the witches’ coven) extract from male predators is kept refrigerated for the next visitor destined to arrive at Grey House. Like Henry he will be punished to sustain its prosperity and existence as a “living thing.”

Laurie Metcalf’s Raleigh is continually surprising in a spot-on, gorgeous performance as the hapless “mom,” who she portrays with power, insight and presence. Of all of the actors, Metcalf is the most surreal yet authentic and empathetic, as we feel for what she goes through at Grey House, though we don’t succinctly understand what we see happening before our eyes. When she is on stage, she is imminently watchable. Her lead, as subtle as it is, guides Caruso’s Marlow and Kipnes’ Squirrel to their understated ferocity which spills out in their insightment to get Henry to masochistically “fall on his own sword,” as they act out their vengeance.

Sparks’ Henry is so likable and loving in his relationship with Maslany’s Max who is the perfect wife, that we are shocked that both are not who they appear to be, Henry less so than Max. Maslany shows a sense of humor with the girls, then turns, flexing her emotional range when she expresses the appropriate terror knowing their luck has changed and she confronts evil. Sparks’ demeanor during the ordeals he is put through is nuanced. His confession is forthright and shocking in its understated delivery.

The silent characters, The Boy (Eamon Patrick O’Connell), and The Ancient (Cyndi Coyne), are vital in their gestures and presence. They add to the dynamic of “the family,” and Coyne’s Ancient is the wounded mirror image of Colby Kipnes’ Squirrel as a youth.

The production is amazing in its confabulation of mystery and opaque unreality delivered by the creative team. These include Scott Pask’s wonderful set design, Rudy Mance’s subtle costume design, Natasha Katz’s stark, atmospheric lighting design, Tom Gibbons’ house humanizing sound design, Katie Gell & Robert Pickens’ wig and hair design, Christina Grant’s makeup design. All of the actors are invested, as is Mantello in relating the otherworldly and arcane side by side with the profane, teasing out humanity in its wild derivations.

In life we see “through a glass darkly.” We receive glimpses beyond what we assume to be “reality” but know there is more that is present. What our senses apprehend, continually deceives us, though we like to believe “we know” and we are in control.

Holloway reminds us of the contradictions, the ironies, the shades of life that have no clear explanation. Indeed, the hints she drops about how the “family” of “willful creatures” operates in this spooky place are never solidified. All is intimation. The “moonshine” as Raleigh refers to it, “sold during the summer,” Marlow names “The Nectar of Dead Men,” which seems a more accurate handle by the conclusion. The duality of symbols existing on a spiritual, preternatural level are contrasted with the profane, material realm, for example when Max makes eggs (they are real-made offstage), for the “hungry, always hungry” sisters-daughters-creatures.

Thus, all is not what it seems. Holloway drives this theme home using the horror-thriller genre conveyance as a grand joke to prod us toward fear and laughter. She sends up that genre and twits us about our nightmares displayed in horror films, mirroring those found in our unconscious in dreams.

The development of the story and its characters, who are timeless archetypes reflected in literature (the good, the evil, the furies who gain vengeance), drive this work beyond genre. Thus, in an attempt to nail down Grey House and dismiss it, one may lose the deeper levels of Holloway’s symbols and complex, convoluted themes. One fascinating example is the red tapestry woven of the sinews of the historical predators, who have come to visit the cabin and whose “Nectar of Dead Men” is distilled for future use. The labels on the jars in the refrigerator tell the tale. The men’s remains we learn are in the walls, the grounds or in the basement which Squirrel frequents.

In Grey House Holloway’s vision expressed by Mantello and his creative team and enacted by the wonderful ensemble is a tonal hybrid of humor, a teasing send up of horror-thrillers, yet terrifying in its deeper representation of the patriarchy which doesn’t come off looking well in its tapestry of innards and crimes committed with impunity finally answered with rough justice, by “willful creatures.” The play is highly conceptual and may bear seeing twice because you will definitely miss connecting elements. Or just enjoy the ride and the fabulous acting and theatricality which will not disappoint.

For tickets and times go to their website https://greyhousebroadway.com/

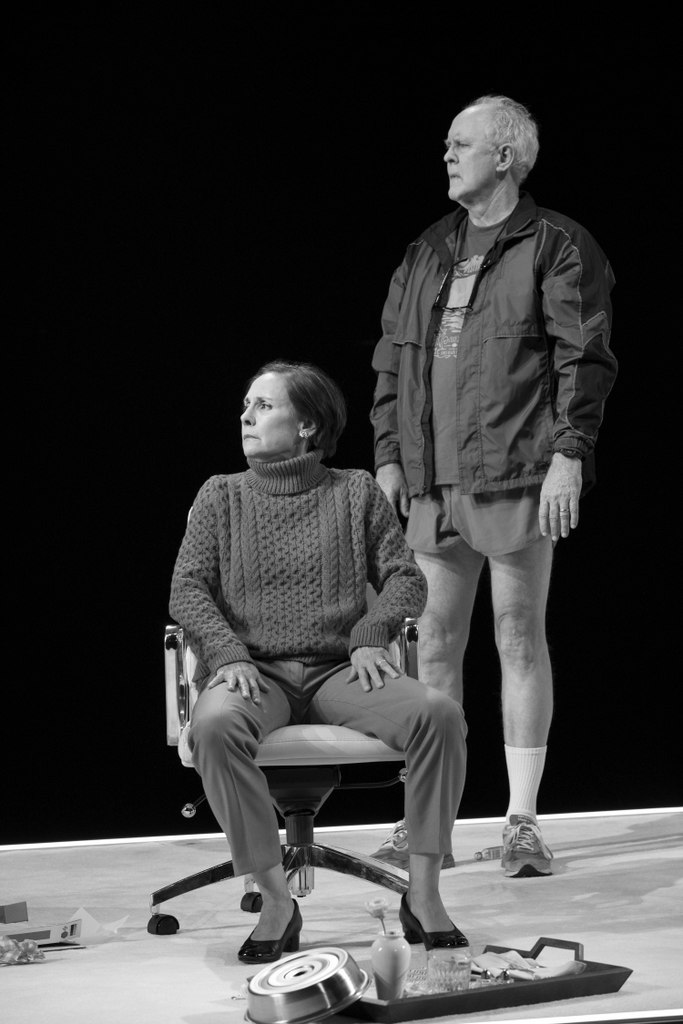

‘Hillary and Clinton’ Starring Laurie Metcalf and John Lithgow

(L to R): Zak Orth, Laurie Metcalf, John Lithgow in ‘Hillary and Clinton,’ directed by Joe Mantello, written by Luas Hnath (Julieta Cervantes)

Hillary and Clinton by Lucas Hnath, directed by the acute, clever Joe Mantello, currently at the Golden Theatre, begins with hypotheticals. Women live their lives in hypotheticals. What Ifs! And this is how the playwright has his character Hillary, who neither looks like nor effects the ethos of Hillary Clinton (played by Laurie Metcalf in a stunning, invested portrayal) opens her discussion in a relaxed “down-to-earth,” “behind the veil” confession to the audience. She posits a “What if?” supposition that there are “infinite possibilities” in our universe.

Hnath wrote the play when Barack Obama was in the full swing of his presidency. Considering what occurred during the 2016 election, Hnath’s play is doubly prescient and its underlying themes resonate more loudly than ever. In 2019 despite #Metoo, perhaps because of it, as much as we’d like to, we cannot pretend that women and men have equality in our culture, especially in light of a Trump presidency which is a throwback to women’s oppression in various forms that echos throughout American History.

For many women, “What if” doesn’t really get a chance to soar to a triumphant conclusion because there are an infinite number of “not possibles” preventing it. The sheer will that is required for women to overstep the “not possibles” is shattering. This is even so in an alternate universe of cultural equanimity, where it is a given that women succeed in obtaining leadership positions because men always lay down their egos and encourage them to do so.

Hnath subtly spins themes about paternalism and gender folkways in his subtle yet not so subtle fictional/nonfictional work. He does this aptly by hypothesizing about one of the most brilliant, competent and ambitious of women in the “free” world living today. Like no other in the political arena, Hillary Clinton embodies the possibilities of power and the smash downs to achieve it. Why is this, Hnath asks sub rosa? He answers this by factualizing his perception of Hillary Clinton’s relationship with Bill Clinton in the service of reminding us about women leadership and competence, about male ego and dominance, about the underlying primal realities of paternalism and male oppression and womens’ attempts to overcome.

At the play’s opening, an always on point Laurie Metcalf as Hillary, posits the probability that on another planet earth somewhere in our universe of “infinite possibilities” there is a Hillary running for the Democratic Party nomination during the 2008 primaries. Hillary, in competition with a man named Barack is losing. With Mark Penn (Zak Orth portrays the shambled-looking, frustrated and stressed campaign manager) Hillary attempts to determine the truth about why she is losing and how she will be able to recoup further losses if she can get more funds to refill her dwindling coffers.

After Mark offers explanations of her loss from his perspective, he indicates that perhaps it is not as bad as she suspects. The Obama campaign actually is daunted by her and has offered an opening for her to be his running mate when he is nominated if she drops out of the next two races and slowly fades away. Hillary interprets this to mean the Obama campaign is circling in for the “kill,” and expresses outrage that she might take such a deal. Despite Mark’s protestations she interprets it to mean she is going down for the count. Mark warns her not to call Bill for help and she promises not to.

Laurie Metcalf, Zak Orth in ‘Hillary and Clinton,’ directed by Joe Mantello, written by Lucas Hnath (Julieta Cervantes)

Twelve hours later, Bill (the wonderful Lithgow) who previously had been kicked off the campaign, shows up in New Hampshire to the starkly minimalistic hotel room (which indicates a lack of funds). When he swears they stayed there before, we consider perhaps this is a backhanded reference to his own campaign in the primaries which he successfully won. In small measure he is forcing her to “eat crow” that she needs him. Then he chides her and expresses his ire at having been thrown off the campaign by Mark.

Their clashes are revelatory. In these discussions they cover a myriad of intriguing subjects: her fear of losing, their lives together, his boredom, her personality, her lack of fire and warmth, that he exhausts her, references to his infidelity and strategies for the upcoming primaries to initiate wins. Some of the subjects are unfamiliar. Others we anticipate because we’ve heard talking heads discuss the Hillary “personality” problem.

Lithgow’s and Metcalf’s focused listening and responding to each other are particularly excellent during Hnath’s dynamic interchanges, well shepherded by Mantello. Importantly, in exploring the fictional/nonfictional complications of a marriage between two brilliant, competitive and ambitious individuals, Hnath reveals the conundrum. They need to be together, but also must be apart in their own identity and autonomy. In their wish to be themselves, they are also the couple in a shared unity and friendship which will end in uncertainty for Hillary and loss for Bill if they separate. The public trust has glued them together as one. Their bond is intangible and ineffable and Hnath particularly suggests this with great sensitivity.

Hnath grounds their arguments, thrusts and parries with homely marriage tropes which we identify and empathize with. They are intensely human, real, warm, vibrant, competitive, loving (their costumes suggest the “all masks off” feel). Underlying all of it are dollops of frustration, wrath, annoyance and fear thrown in for good measure.

Threaded throughout we understand that these two have a profound relationship based on many similarities and attractions based on differences. They have a mutual care and concern that is their greatest grace and their underlying curse. Indeed, Hillary, in anger wishes she could break away from the stench of Bill that follows her. But when he suggests to succeed she must get a divorce, she avers. It is a fascinating moment; for as she states, she knows that many would support this and believe this is the right action for her to take. However, she cannot; she states she will be with him forever. For that he is beyond grateful.

Into this mix is thrust the knowledge of a phone call between Hillary and Obama, during which Hillary accepted Obama’s offer to be his running mate. Upon this everything turns.

Laurie Metcalf, John Lithgow in ‘Hillary and Clinton,’ directed by Joe Mantello, written by Lucas Hnath (Julieta Cervantes)

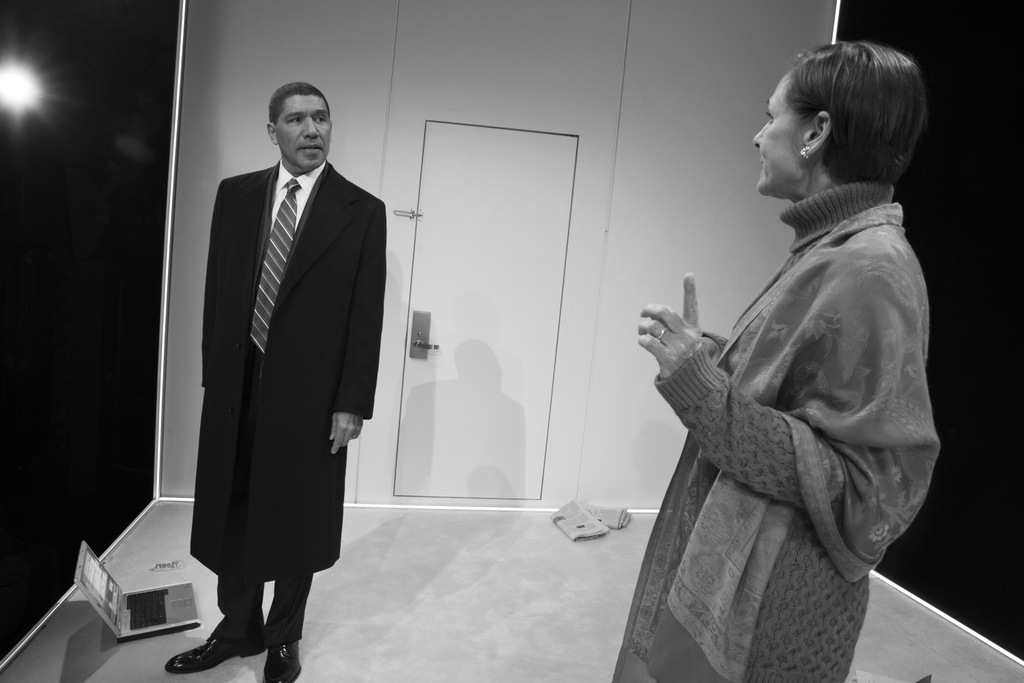

When Bill steps into the campaign and gives her what she initially requested, he also oversteps his bounds causing rifts between Mark and Hillary. This causes a surprising series of events, one of which includes Barack coming to their hotel room to talk. Barack is portrayed by Peter Francis James in an interesting turn and resemblance to Obama in demeanor and stance. Barack confronts Hillary about the offer to be his running mate and the change in the fortunes of a race, after Bill becomes involved. He also reveals a tidbit of information that landed in his lap, information which will haunt the Clintons in the future.

There is no spoiler alert. You will have to see how Hnath arranges the chips to fall in this climax and how all of what we’ve seen before of their ties that bind, play out.

The play which expands on the premise of “infinite possibilities,” ends on it. From Hillary’s initial flipping of the coin that turns up a 50/50 heads/tails pattern of probabilities, we follow a series of events that decry any possibility of the coin toss dealing Hillary a winning hand. Hnath has brought us closer to explaining why she is not a winner this time, nor a winner in 2016, nor ever unless the earth tilts differently on its axis to produce another earth where Hillary somewhere “over the rainbow” on another earth is president.

Hnath allows us to fill in the unanswerable uncertainties and questions which he leaves open and encourages us to hope for in his poetic “on another earth Hillary is president.” For me this is heartbreaking especially now with the Mueller Investigation revealing a massive Russian warfare campaign to interfere with the election to put Trump in as the president, the results of which we are being deprived of in its full form. Indeed, Hillary lost the 2016 election on planet earth. She did this, perhaps for the reasons suggested intriguingly in the play.

However, Hnath’s powerful work and framing it with the backdrop of probabilities reveals more in what it doesn’t discuss because it was written before we understood what forces were ranging against the United States. Probabilities set up in coin tosses are random. What happened in Hillary Clinton’s 2016 loss (which is never alluded to in the play) is far from a probability. As more of the facts come out (despite the struggle to obfuscate and obstruct the report by the administration) her loss appears to be an inevitability…an inevitability which various illegal forces would go to extreme lengths to bring about.

peter Francis James, Laurie Metcalf, ‘Hillary and Clinton,’ directed by Joe Mantello, written by Lucas Hnath (Julieta Cervantes)

That this production is being presented now at the height of the issues with the release of the Mueller Report Investigation and the DOJ? Well! This is fascinating and curious. And it leads me to this theme: there is more to what appears to be so, what pundits say is so and what “the facts” are depending upon who “owns” them. In Hillary and Clinton, Hnath presents the “What If” and allows us to consider what the character Hillary says about running again at some point. She would like to; she must understand how to get there to win.

This forces us to ponder what happened in 2016 and then the character Hillary brings us back to the coin toss which makes her president on another earth. We go with Metcalf’s Hillary for one second, then are dropped into the pit of reality. She isn’t president. And why not? Because of Bill? Because of her personality? Because of the Clinton Foundation? Because of paternalism? Because she is a woman? Sure!

But!

To my mind, Hillary Clinton’s loss was less about her personality and her relationship and Bill’s “stench” and more about what forces didn’t want her in and why not. All the ultra-conservative social media groups, Russian Intelligence institutions, Russian hackers, Republican Think Tank strategists, elite globalists and like-minded billionaire Americans were poised to prevent her win with systems “ON.” It was a monumental effort that is mind blowing. And very costly.

That’s why Hnath’s character Hillary tossing a coin at the beginning and conclusion of the play is brilliant in theme and profound message. It is frightening, heartbreaking and an eye-opener, however you frame the “What if.” There will never be a “What if” for Hillary. There is no alternate universe, earth or whatever. We must deal with what is and get to work about it.

Laurie Metcalf is gobsmacking; she’s nominated for a Tony, Drama Desk and Drama League for “Best Actress in a Play.” Lithgow is superb. Able assists, Zak Orth and Peter Francis James make this a play you must see. Hillary and Clinton will make you think; it will open your eyes. And as it did for me, it may break your heart.

Hillary and Clinton runs at the Golden Theatre (252 West 45th St.) until 21 July. It has no intermission. You can purchase tickets by going to the website and CLICKING HERE.