Category Archives: Broadway

‘Mrs. Doubtfire,’ a Family Musical Comedy That Is Present and Sorely Needed

It is to the credit of the producers and creative team that they have taken another approach to the iconic 1993 film Mrs. Doubtfire (starring beloved Robin Williams) by enhancing its vibrant situational humor with emotional musical resonance in an adaptation currently on Broadway at the Stephen Sondheim Theatre. Thankfully, Doubtfire (music and lyrics by Wayne Kirkpatrick and Karey Kirkpatrick; book by Karey Kirkpatrick and John O’Farrell) reminds us of the vitality of timeless verities, unity despite division, love despite differences, compromise toward the best solutions possible. Mrs. Doubtfire reveals that with love and faith all things can work together. And a sense of humor helps.

How the actors, director, technical team configured the book and music to emphasize these themes is the focus of this reviewer. If you are looking to be entertained by Doubtfire opprobrium, stop reading now. I thought the production of Mrs. Doubtfire, shepherded by the always fine director Jerry Zaks, hits its mark. Audiences are loving it, if critics are twisting its worth unjustly and inanely to make it their footstool to appear “clever” and in vogue.

Based on the titular Twentieth Century Studios Motion Picture, the Broadway adaptation deepens the comedy and characterizations of Daniel, Miranda and the children with its musical numbers (“I Want to be There,” “What the Hell,” “Let Go”). In these we understand the emotional price and the grind that a family endures in the grip of a painful divorce when it is too arduous to work through the seemingly limitless difficulties.

Lydia, the eldest daughter, leads the ensemble, Miranda and Daniel to expose the conflict between her parents and indicate how it is derailing all of their lives. This happens during a photograph sitting Miranda has arranged in the hope of cataloguing the kids’ ages. Daniel upends Miranda’s wish for a family photo when his shenanigans, which are funny and endearing, work the opposite effect on Miranda and ultimately destroy the photographer’s camera, disappearing any chance for a photo. Lydia (the excellent, on-point Analise Scarpaci) and the others note the handwriting on the wall and imminent divorce in the opening song “What’s Wrong With This Picture.”

The irony is that Miranda wants a reassuring picture of a happy family, and Daniel, despite himself, is not able to give that photo, representative of the family she wants. Both parents are disunited, not in sync, skewed. One is reminded of the Facebook photos people post of themselves, i.e. the “wildly loving couple” who behind closed doors, is completely miserable. Fronting on Facebook and inciting jealousy in their “friends” is the only modicum of happiness they can suck out of the relationship which is doomed.

Likewise, the symbolism of the scene and the song are clear; the differences between this couple run deep into life approaches and right brain, left brain schematics. Miranda is organized and ambitious, intending to be her own entrepreneur. Daniel, a voice actor is highly imaginative, creative, his own person and all heart. The kids are the bridge, but instead of being the way to cross over and make the most of each parent’s attributes to benefit the family dynamic, the “adults” exploit the kids who become the linchpin to make each other miserable, incapable of navigating productive “family” roles and interactions. Each sees the other as “obstructive” and wants the other to be more like their own perspective of a “Dad” and a “Mom.” Their inflexibility is ultimately self-destructive and as in many families makes divorce inevitable.

Lydia gets it; her parents and siblings are in denial; the ensemble concurs in the refrain. Daniel is belittled and made to appear unfit by Miranda who casts herself in the role of mother superior, a termagant. She ironically justifies herself, placing the blame on Daniel’s behavior, annoyed that “he” has made her into the woman she “swore she’d never be.” Clearly, both are revving each other’s engines and are at fault, but circumstance, Daniel’s fears and Miranda’s overwrought nature lay the brunt of the fault at Daniel’s door, and he accepts this, a clue to his heart and future flexibility to change.

When he breaks her rules by taking the kids out of school to have a birthday party for son Christopher (the appropriately gangly, awkward Jake Ryan Flynn) and a stripper shows up by mistake, Miranda is provoked beyond forgiveness. It will take a miracle for Miranda to ever compromise with Daniel again. Thus, the set up for the miracle of Mrs. Doubtfire is born after the divorce is finalized by the end of the song “What’s Wrong With This Picture.” However, the irony of Daniel’s wacky “picture” continues when unsuspecting Miranda hires him for the Nanny position and his appearance and gender is skewed but not his heart. The photograph metaphor which threads throughout (Daniel is even removed from Miranda’s photo wall) is finally corrected by the musical’s end (“As Long As There is Love”).

Miranda (the lyrically voiced Jenn Gambatese who gives a nuanced performance showing Miranda’s growth in forgiving Daniel) remains unmoved when Daniel pleads his case in family court to receive joint custody in “I Want to Be There.” As Daniel, Rob McClure’s petition to the judge is beautifully heartfelt and stirring. Indeed, throughout, McClure’s skills (singing, voices, break dancing, dancing, rapping, looping, hand puppeteering) and exhaustive energy and enthusiasm in a role that requires he be present in season and out are incredible. He makes Mrs. Doubtfire his own, and as a result she is authentic and real.

This authenticity McClure conveys to the hilt so that you forget he IS Doubtfire and are surprised when he isn’t. This switcheroo becomes all the more hysterical when he uses the voice of Daniel, dressed up as the plump but extremely agile elderly Scotswoman and then reverts to Doubtfire’s voice when he is in the role of himself as Daniel. This occurs a number of times i.e. auditioning for Miranda on the phone, with son Christopher when he blows his cover and as he prepares for a surprise visit by court liaison officer Wanda Sellner (the extraordinarily voiced Charity Angel Dawson) who is checking his apartment to make sure it is fit for visitation with his kids.

When we see the transformations and costume (Catherine Zuber) wig (David Brian Brown) make-up and prosthetic changes (Tommy Kurzman) which occur in the twinkling of stage time’s eye, we are amazed at the “seamless” effort it takes. Kudos to the team for making it so. The switches are humorous and crucially revealing: each time McClure’s Daniel redeems himself being Mrs. Doubtfire, we know it is for the love of his children and to gain his self-respect. Though the deception is morally questionable, it is forgivable because his portrayal is award winningly brilliant and endearingly wise. Ultimately, it is the step which fosters understanding, allows Miranda breathing room to be her own person, and brings the family closer together.

Humorously wonderful scenes occur throughout. One is when Daniel calls on his brother Frank (the hysterical Brad Oscar) and his partner Andre (the magnetic J. Harrison Ghee) for help to make him into the iconic Nanny that Miranda cannot refuse. After costumers and hair and wig designers Frank and partner Andre run through a roster of amazing women (female ensemble members show up as Cher, Jackie O., Donna Summers, Diana Spencer, etc.) that emerge from their talented fingertips in “Make Me a Woman,” Daniel avers that his role is a Scottish born widow past 60. Changing course, they produce versions of their perception of iconic women of a certain age who are the antithesis of the glamorous fashion icons that paraded across the stage minutes before.

Out come tall, diesel men dressed in the same outfit (a forerunner of Doubtfire’s) pronounced to be Janet Reno, Eleanor Roosevelt, Margaret Thatcher, Julia Child and a masked Oscar Wilde in a farcical getup. The irony is hysterical: it twits Andre’s and Frank’s viewpoint and disdain of the unfashionable but formidably strong women as not being the “feminine” ideal. The idea of what constitutes a “woman” and genderism is turned on its head by Andre and Frank, which reveals lightening wit that certainly will offend some critics because it is daringly in your face.

Tragically, what is “politically incorrect” in one part of the country is searingly popular in another; so the criticism of the production being outdated in terms of genderism is slim-sighted, considering that culturally/geographically not even sections of New York City maintain the current “correct” views (i.e. Staten Island, Beach Channel, Breezy Point) related to gender. Many in these areas, including upstate New York (one of the supposedly most liberal states) take offense at “political correctness.” What to do?

In another LOL scene when Frank and Andre visit Daniel to deliver an additional wig for his new Nanny role, Wanda Sellner (the coldly autocratic court appointed officer) visits Daniel’s apartment, interrupting Frank and Andre’s mission. What ensues is a fast-paced quartet of dramatic irony as Frank, Andre and Daniel try to front an increasingly suspicious Wanda Sellner about whose sister the elderly woman is and why Daniel as Doubtfire (who has lost his prosthetic device out the window) won’t look directly at Wanda Sellner, which he finally does with banana creme pie on his face that makes him unrecognizable.

That the audience has been let in on the truth about Doubtfire’s gender, his “losing face-out the window” and Frank’s shouting nervously to cover his lies, makes the scene all the more riotous. Dawson is superb in her fierceness which escalates the humorous tension that the men and the audience feel as they fear Sellner’s hound-like nose will sniff out Daniel’s deception.

Brad Oscar’s priceless screaming delivery is tuned to rhythmic sonority with assists by straight woman Charity Angel Dawson and J. Harrison Ghee to bring on the belly laughs. Their crack-fire delivery accompanies Rob McClure’s costume and voice switches portraying two individuals at once in split second lag time. The tension only subsides with the audience’s audible sigh of relief, when Andre (Ghee) posing as the FBI on a phone call to Sellner rescues Daniel from Sellner’s adversarial, witchy clutches which gain steam and develop in Act II.

Zaks’ direction to shepherd the quartet’s superb pacing achieves a rhythm that is glorious and pitched for gales of laughter. By this point the audience is rooting for Rob McClure’s Daniel, taken over by his incredible sincerity and loving father/mother, man/woman Mrs. Doubtfire. Indeed, men do well as women, a gender trope that one must not miss if one is “getting it all in,” “going with the flow” and not luxuriating and indulging one’s sensibilities in offense at the genderisms the writers play off of. Importantly, another theme underscored by Mrs. Doubtfire is that that rigidity (from the political right or the left) whether it be in forcing others to adhere to one’s expectations or deeming “the way one should be” provides no easy answers or road to compromise. It indeed takes time and openness and flexibility and kindness for compromises to be reached.

Daniel masters Miranda in an area of vulnerability by making himself invaluable as the Nanny and housekeeper assuming motherly roles, while Miranda stokes her entrepreneurial skill. Additionally, he attempts to satisfy his court requirements to maintain a job, securing one as a janitor for a TV station. It is in this scene that we are introduced to an outdated children’s program which steers us into hilarity provided by the exceptional Peter Bartlett as Mr. Jolly. As Jolly, Bartlett bumbles and fumfers telling time with puppets Ratty and Mousey. His producer boss Janet Lundy (the stone-faced, funny Jodi Kimura) groans about being fired unless the Mr. Jolly Show is updated to snap and pop. Bartlett’s pauses, musing and timing as the near doddering Mr. Jolly is smack down LOL organic. This scene is cracker-jack great!

In attempting to bring order out of chaos at the Hillard home, as Doubtfire, Daniel sets the kids doing their homework (turning off their phones, etc.) and receives cooking lessons from Chefs Amy, Ann and Louis who appear from his tablet magically to show Doubtfire how to cook a “nutritious, delicious meal,” in record time, including how to spatchcock a chicken. In “Easy Peasy” Rob McClure and the ensemble in well coordinated, rapidly timed moves gyrate around the stage. He grandly catches a chicken and sticks of butter that fall from the ceiling as the ensemble sings and dances. During this wild cook-off, look for the hysterical pharmaceutical commercial break by a Rectisol Doctor (David Hibbard) complete with list of side effects including death.

The meal which smokes Daniel out (a take-off on the film when Williams sets Doubtfire’s breasts on fire) gives him an appreciation for Miranda’s home cooked meals. Failing once more, he orders take out which he then arranges in a finely set table for Miranda, the kids and her work partner Stuart who intends to be her beau. The hilarity ends in revelation; he lost his place at the table, and Mrs. Doubtfire won’t replace him there. He has the growing realization that he will never be back at that table as their Dad, and in fact Doubtfire is an encumbrance to what he really wants, back in Miranda’s good graces. The impetus becomes if he is to see his children at all as their Dad and not the character he has created, he must get a job that can pay an affordable living wage.

The opportunity arises when beat box artist Loopy Lenny, a guest on the Mr. Jolly Show, leaves his “loop machine” which Daniel cannot resist playing with as he mops the area. In “About Time,” Daniel loses himself in remastering a cooler version of telling time with Ratty and Mousey that crackles with his exceptional voice skills. Upon hearing his genius at work Janet Lundy is impressed to offer him the possibility of a job on the show. With hope of this new job, Daniel digs in as Mrs. Doubtfire having reversed all he had contributed to making a disaster as their Dad. In “Rockin’ Now” Mrs. Doubtfire leads the ensemble in Daniel’s self-affirmation, lifted out from Miranda, his kids and Frank and Andre’s perception of him as a loser. He sees himself as a brilliant fixer and vital, purposeful individual.

A number of points are made during this hysterical number where McClure’s mobility with 30 pounds of rubber dancing and twirling Doubtfire’s plaid skirt is beyond funny and delightful. One is that Daniel could only change and express his loving heart with a wall of rubber separating him from those who saw him negatively and didn’t know how to encourage his goodness (a shortcoming of theirs). Secondly, as a character he is able to do that which he resisted as Daniel, who continually provoked Miranda. Conning her and the kids is a weird kind of payback proving he is as superior as she presented herself to be. However, when Lydia and Christopher discover who is under the rubber, the question remains, how long will Daniel be able to front Miranda and Sellner who hold the power of his rights as a father?

In Act II the risks of discovery become greater as Lydia and Christopher watch their father pull off Mrs. Doubtfire as a plus size model, showing Miranda’s sportswear line as he and the Ensemble models sing and dance in “The Shape of Things To Come” for an audience of buyers and store representatives. Dressed in a colorful skimpy outfit revealing a sports line for “all shapes and ages,” once again Daniel’s phenomenal talents save the day and get deep pocket customers for Miranda kicking off her entrepreneurship. In the song’s lyrics, the shift from actors with BMI 20 figures proud to look in the mirror to Mrs. Doutfire’s 30 BMI figure that can do extraordinary moves is a telling slap in the face to the guilt inducing diet and weight loss industry: a great irony.

Mrs. Doubtfire has made a world of difference for Miranda who is beginning a relationship with Stuart (“Big Fat No”) and resolving the end of her relationship with Daniel (“Let Go”) who is miserable (“Clean Up The Mess”). In a conundrum obstructed by having to be Mrs. Doubtfire as he grows invisible with his children, he faces a reckoning with Sellner who puts together the viral Doubtfire sports model video and other information she receives from Miranda about Daniel. The reckoning begins in Sellner’s office when Daniel is supposed to appear with “his sister” Mrs. Doubtfire and turns into a surreal scene with Sellner as a magical, witchy type spirit proclaiming his doom in “Playing With Fire.”

Charity Angel Dawson pulls out all the stops wailing retribution for him in a shimmery red/orange dress against a fiery backdrop as a chorus line of Doubtfires send off Lydia, Chris and Natalie (Avery Sell) away from him presumably forever. Then the ensemble Doubtfires close in on him, singing the refrain, “The Truth Will Make You Free,” while sweeping their brooms in a haunting dance as Sellner sings her glory. And eventually the power of Sellner’s presence and voice along with the Doubtfires circling, engulf him dressing him in the hated Doubtfire costume and persona. The backdrop and set returns him to Miranda’s house where the final arrangements are set in motion for his big reveal that ends the charade once and for all (“He Lied to Me,” “Just Pretend”).

However, the truth with his reveal results in his redemption and Miranda’s acknowledgement that his true heart had to masquerade as Doubtfire for a time to show her and him what he was capable of. Additionally, with his new job on a TV Show starring Mrs. Doubtfire, the family is reminded of Daniel’s goodness. With the help of Sellner who shows her true colors and acknowledgement of Daniel’s love for his children, Miranda is convinced that Daniel must see and take care of Natalie, Christopher and Lydia with a joint custody arrangement (“As Long As There is Love”).

I have nothing but praise for Mrs. Doubtfire which is a whirlwind of emotion, comedy, farce, genius pacing, singing, dancing and crisp dialogue acutely directed and performed by the prodigiously talented Rob McClure who is breathtaking, as the other actors shine equivalently in their roles to assist him. The music, a combination of pop, hip hop, ballad and more functions to raise the emotional stakes at each turning point and grows from Daniel’s and Miranda’s struggle with each other. Mrs. Doubtfire’s book is well adapted by Kirkpatrick and O’Farrell and runs deep in this production because of the songs (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick) their symbolism, the hybrid comical farce and continual pushing of the envelope to embrace Daniel’s guilt and imagination (“Playing With Fire”) (“Easy Peasy”).

Kudos to Ethan Popp for musical supervision, arrangements and orchestrations. Special kudos to Lorin Latarro for her choreography. Both bring a myriad of new elements to Mrs. Doubtfire and make it shine greater than the film.

The technical aspects (movable sets) are well devised for speed, and are well thought out and wrought for the quick scene changes and farcical, magical moments mentioned. Kudos to David Korins (scenic design) and Philip S. Rosenberg (lighting design) and Brian Ronan (sound design) as well as aforementioned Catherine Zuber, David Brian Brown and Tommy Kurzman. I loved the lighting and outlines of the cityscape, the Hillard household and touches needed for the success of various scenes (“Easy Peasy”).

The production is a superb adaptation combining the known and the new. It should be seen a few times because inevitably, there is so much to glean you will miss the symbolism and the profound characterizations which appear stereotypical initially, but are resonant and vital as are the themes mentioned. For tickets and times go to their website: CLICK HERE.

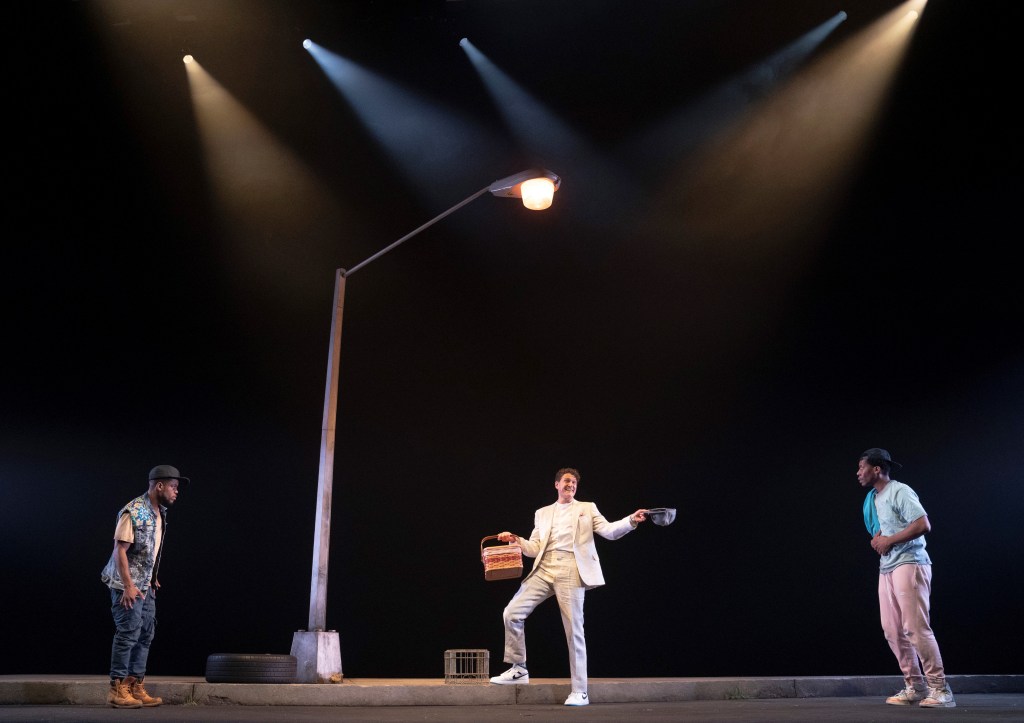

‘Clyde’s’ by Lynn Nottage, a Devil of a Comedy at 2NDSTAGE

Lynn Nottage’s play Clyde’s presented by 2nd Stage, currently at the Helen Hayes Theater, is an intriguing switch off from her dramas for which she’s won two Pulitzer Prizes (Sweat-2017, Ruined-2009). Nottage is the first African American woman to do so. Clyde’s combines ironic and other-worldly elements with comedic twists galore and an expose of problematic cultural issues that empathy and social unity help to resolve. Her hybrid work lights a path for playwrights who want to stretch their own talents. Additionally, the uniquely defined characters and situations, which show she is unafraid to push the envelope, indicate that she will continue to evolve as an exceptional playwright. Clyde’s exemplifies the best of Nottage in “spades.”

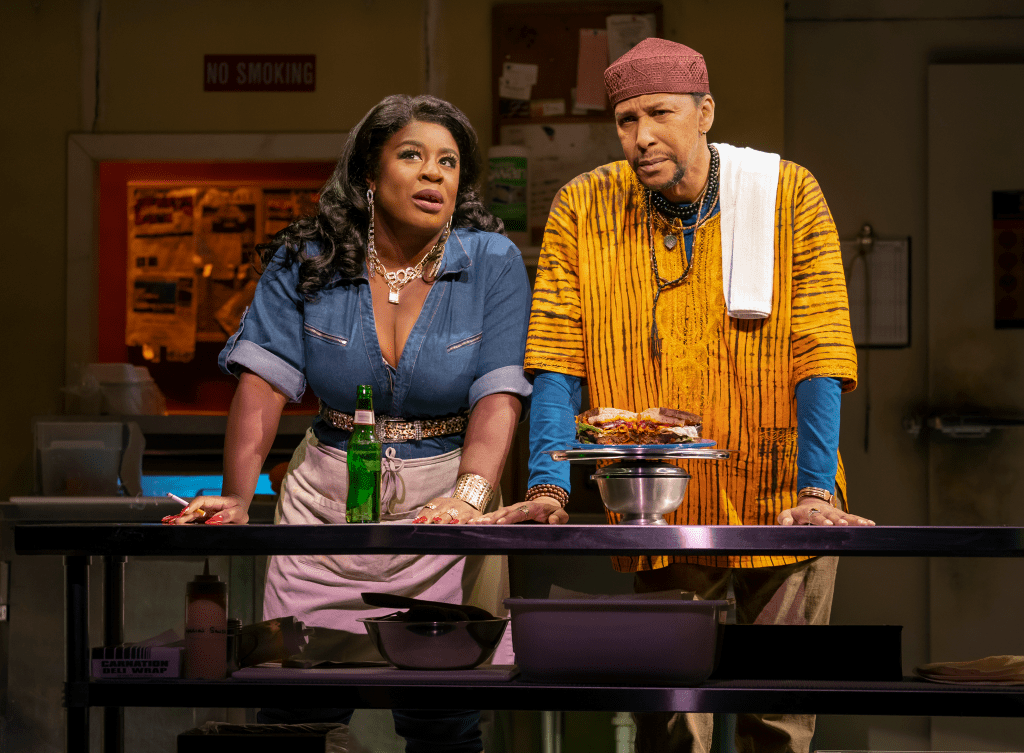

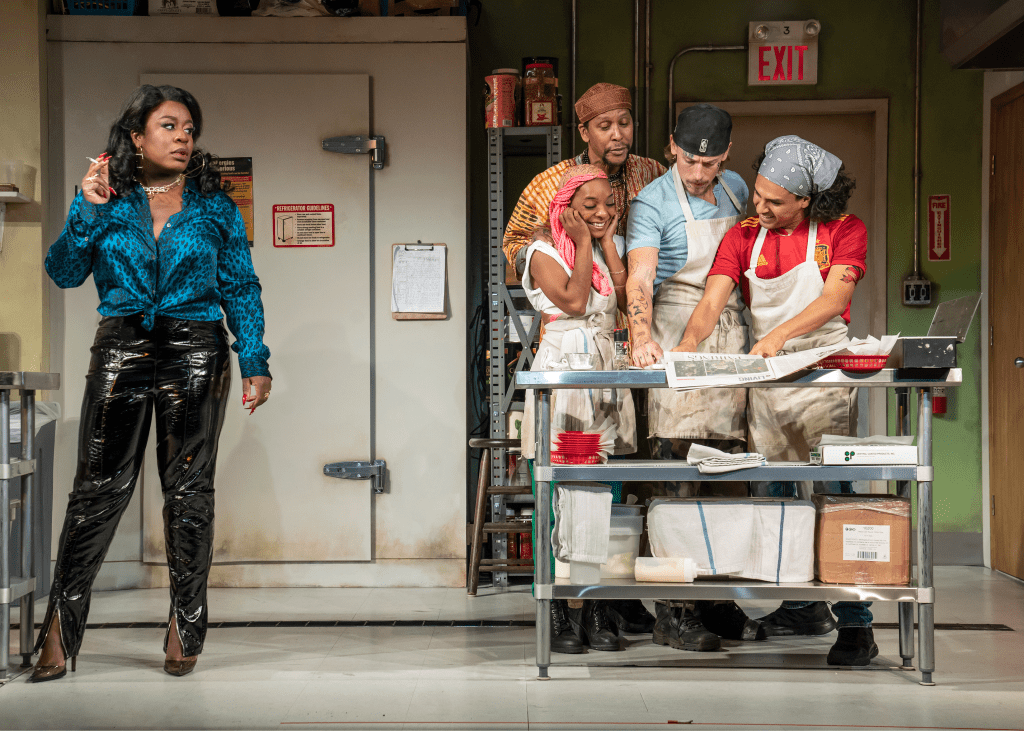

Acutely directed with precision and grace by Nottage’s long-time collaborator Kate Whoriskey, Clyde’s highlights a group of down and out former convicts newly released from prison who can, to their great misfortune, only find work as cooks at the greasy spoon, truck-stop diner in Berks County Pennsylvania known as Clyde’s. The joint is named for its owner (the electric and terrifying Uzo Aduba), who operates it with a hands on approach and who is an insidiously bullying and unapologetic former convict herself.

Nottage has humorously configured Clyde as the mythic female “biach” employer who is hyperbolic and cruel in all her ways. She is the type that sends grown men screaming to the bathroom to do a line of coke, so they don’t brain her with a meat mallet. She is the malevolent force that sends women weeping into the arms of their former brutal lovers seeking financial support, so they don’t have to suffer her wrath ever again. Indeed, the sadistic dominatrix is the last person on earth you would ever want to work for. And as such, she’s an outsized and marvelous character, as delectable as Montrellous’ scrumptious sandwiches.

Uzo Aduba as Clyde brings the laughter and fear, having a blast violating every politically correct action and attitude toward the new ex-con addition to her cooking staff. Ironically, he is, a white supremacist in hiding (portrayed beautifully by Edmund Donovan), who is laying low to keep the job, and trying to make the peace with his three black/hispanic co-workers, who at another time in his life, he would have scorned and abused.

Clyde breathes fire over the veteran staff like a dragon-lady. They include the chef guru sandwich maker/leader Montrellous (the wonderful Ron Cephas Jones); Rafael (the hot-blooded, sensitive, full of life Reza Salazar); and the empathetic, dynamic Letitia. Portrayed with nuance by Kara Young, Letitia eventually stands up to Clyde with impunity. By the end of the play, we come to know the deep, resilient and loving core of each of these former convicts down to the reason why they went to prison. And we understand that in each of their former lives, there, but for the grace of God go any of us.

Nottage’s craft and Whoriskey’s incisive shepherding of her actors to encourage their spot-on authenticity allow us to stand in these ex-cons’ shoes and wish that every good thing might happen to them. Of course Nottage has us especially wishing they escape the claws of the sinister Clyde. Indeed, though Clyde appears to be looking for any excuse to fire them and return them to the Arctic reaches of emotional devastation from whence they came, perhaps her tough discipline and brutality does reveal a knowledge of how to help ex-cons succeed. At the least her iron discipline betrays a good heart somewhere behind the wall of titanium armor she’s had to create to confront a callous society. She makes it very clear that she is as hard as concrete to survive in the culture that would see her dead and forgotten, rather than help her climb out of the abyss ex-cons face upon release back into the environs that indirectly provoked their prison sentences.

The explosive situation yields a myriad of possibilities as Nottage and Whoriskey unspool the relationships among the cooks who eventually form their own solid community led by their sensei Montrellous. Cephas Jones is masterful. His Montrellous quietly motivates the staff to make the “perfect” sandwich which embodies the goodness of life and manifests the sublime taste of everything beautiful that artistic foody genius expresses. Montrellous is likened to a Christ figure of love, peace and encouragement against Clyde’s Satanic, sardonic, sadistic boss woman, reputed to have made a “deal with the devil” to keep alive Clyde’s her reason d’etre.

It is rollicking fun to watch Jones’ Montrellous and Aduba’s Clyde as they confront each other in a dynamic relationship that begins at the top of the play. Montrellous tantalizes Clyde to taste his heavenly sandwich as he shares a story of his past. She humorously resists him in never sampling the goodness he’s created, nor agreeing with how he’s conducted himself. Immediately, we understand who both are; Clyde is unrelenting in her icy, dark approach toward humanity. Montrellous is open-hearted, light-filled and clever. He teaches the staff that the fastest way toward amity is through the hospitality and deliciousness of something home-made with love. Of course Clyde resists him. Their relationship is symbiotic until it isn’t.

Nottage moves the play briskly forward as Clyde, the ever-psychically draining task-master compels her cooks to sling out food that lures truckers hungry from their long hauls. Montrellous peacefully sidesteps her attitude and encourages his mates to their high calling of making the enlightened sandwich to bring them the pride and strength of this new calling. As the food is plated, Clyde pops up at the window where she collects their sandwiches, dishing abuse, making searing quips and sizzling taunts. And when she enters the kitchen, they must watch out, for her snarky epithets may turn physical to keep her charges in line.

This comedy with a profound message insinuates itself with flavorful intricacy. Soon we’re hooked. How, when and where our favorite ex-cons become the chefs that Montrellous inspires them to be, despite working in a hell hole and at cross-purposes with a seemingly malevolent tiger-lady, who pushes them to the emotional brink to fail, is a revelatory sight to behold. You will just have to see the play for the organic process of how the hopes of the ex-cons and Montrellous’ faith in humanity spins out by the conclusion.

The themes are all there in Nottage’s merry-go-round of antic figures. The culture has ground down these sterling individuals and deprived them of encouragement and self-love so that they’ve landed in prison through a single act. This is an indictment Nottage presses. Additionally, she suggests individuals like Clyde can become like devils pressured to abuse their staff in order to tow the bottom line.

Even a small dive like Clyde’s reflects a microcosm of the corporate macrocosm of abuse. What happens in Clyde’s, as humorous as it is, speaks volumes. It is representative of the monumental struggle that exists between the “right to work” tyrannical employer, for whom constitutional rights do not exist, and those who need to survive and will take any job that they can get. Indeed, Nottage’s sub rosa theme is there must be a better, more decent way. And of course, through the attitude and mien of Montrellous we see it enacted, encouraged and through it, a way of escape for the ex-cons.

Clyde’s works on so many levels. One may appreciate the raw humor, the symbolism, the characterizations which are priceless and memorable and the vital and current themes. This is a play of representative men and women, who have had to work terrible jobs to put food on the table. Finally, the play speaks to those professional or amateur chefs who love to eat and prepare “the food of life,” so that others may come and receive health, wholeness and love. Look for the especially salient themes. You will not be disappointed and may even fall in love with this unforgettable production.

Final kudos go to the creative team whose set design, props (real sandwiches…yum), lighting effects, sound and costumes help to hit this out of the theater ballpark. These include Takeshi Kata (scenic design); Jennifer Moeller (costume design…I loved Clyde’s jazzy, sexy outfits for a truck-stop hostess); Christopher Akerlind (lighting design…there were dimmed lights for Montrellous’ sacred, life-changing sandwich); Justin Ellington (sound design…his eerie music was appropriate for the sacred sandwich); Cookie Jordan (hair and wig design). Finally, Justin Hicks’ original music was spot on for the tone and tenor of Clyde’s.

This is the perfect production for this time of year or any time of year. For tickets and times visit the website: CLICK HERE.

‘Diana the Musical,’ Starring Jeanna de Waal, a Foray Into the Tabloids

Billions of words and their attendant photos have attempted to characterize The Princess of Wales, Diana Spencer, including the statements she contributed in her well publicized television interviews. Regardless, the many iterations of her life (Diana the Musical, Spencer, The Crown, documentaries, etc.) are fictionalized. We will never know the true details of her story nor move beyond the tip of the iceberg, though much has been made of The Crown’s accuracy.

As a result any commentary, criticism and discussion about the fictions that are presented with or without music related to her life are disingenuous. It is a sly continuation of what raised her to glory and contributed to her death. Recognizing that I am one of the hundreds of journalistic hypocrites, I prefer not to pile on adding to the glossy, hyperbolic, acerbic criticism that has been written about Diana the Musical, directed by Christopher Ashley, currently at the Longacre Theatre.

In this review, I look “through a lens darkly” at the musical with the intention of praising what may be the salient artistry of the production and avoiding the “critics’ mess.” At the least, Diana the Musical will add to the overall evolution of musical theater, for good or ill. As such it should be viewed with more than blindly gleeful excoriations.

The musical, backed by the Schubert Organization and a boatload of other renowned producers, including La Jolla Playhouse, is the work of the creative team of Joe DiPietro (book & lyrics), and David Bryan (music & lyrics). The team won Tonys for Memphis (2010), and other awards, including DiPietro’s Drama Desk for Best Book of Nice Work If You Can Get It. Bryan, a founding member of Bon Jovi (keyboardist), is a Grammy winner. And both have teamed up on their next musical Chasing the Song, also workshopped at La Jolla Playhouse.

The key to understanding their perspective about Diana The Musical is at the top of the production. Right before it begins with its bang-up opening number, “Underestimated”, six PAPARAZZI dressed in tan, flared overcoats with matching hats, looking like “spies” appear amidst flashes of light. Rapidly, like Thespis, the first actor to go solo from the chorus in ancient Greek theater, one PAPARAZZI steps out and says, “Was there ever a greater tabloid tale?” Then all race off.

From the bright light backdrop emerges Diana, the golden-throated Jeanna de Waal, who pulls off the waggish theatricality and endearing Diana persona with great flare and emotional nuance. As she sings “Underestimated,” we are reminded that she, the Diana avatar, upended everyone’s expectations and made waves, changing the nature of the monarchy as perceived by the British tabloids and vulture media, astutely turning their word swords into their own “proper entrails.”

Thus, with this PAPARAZZI’S “greatest tabloid tale” establishing the “smart-alecky,” flippant tone, approach and poignant conclusion, we understand the creators’ vision and the development of Diana The Musical as a “tabloid story” in what follows to be a flashback of the press’ “facts” of her life with the royals. Importantly, we are thrust into examining ourselves as the consumers, predators, voyeurs that kept and still keep that story “alive,” the facts confused, and lines, between fictionalized gradations of truth, blurred. As the production infers, the tabloids of the time, principally those of the Murdock empire, became the staging ground for the launching of the princess. They keenly, exploited this image for its money-making potential with suppositions and crass lust for gossipy sensationalism that the public and above all “journalists” “ate up” and still consume in musical plays.

To confuse the medium that the creators expose in all its lurid tawdriness with the conveyance of the subject matter (the production), which twits and exposes the tabloid’s boorish insensitivities is an arrogant presumption. It’s as bad as Facebook’s misinterpretation of sardonic irony. Facebook’s algorithms don’t “get” irony; their robotics are literalists incapable of understanding nuance, irony, sarcasm, ridicule.

Likewise, to view Diana The Musical as a literalist caught up in the arc of the story, clicking off the remembered events one may have consumed from the tabloids, papers, TV series or documentaries, one misses the humor, irony and the sometimes intentionally sophomoric rhymes and cleverly repetitive music. The repetition implies Diana copy was all of the same piece. Additionally, one will miss the unfolding of the final revelations and themes: that tabloids spread misinformation because they can with a believing populace; tabloids act as an equalizer of the great to bring them low to sate the sub rosa jealousy of the “little people;” tabloids mine humiliation, create torment and demean by erecting idols then smashing the “adored” with their humanity. Murdock’s tabloids propelled the Diana “story” and gossipy dirt like no other.

Revolting? Indeed, and that’s one of the points of the musical. Enjoy it and burn yourself with understanding. Don’t enjoy it, see its “messy crassness,” you miss the production’s raison d’etre and specifically miss this point: the tabloids encouraged the spin of the public’s belief in “the people’s princess,” then damned her for being what they created. They adored her above the Queen and royal family but were jealous of her and slapped her continually each time they covered her. Ironically, they yearned for her death, indirectly causing it so they might mourn a tragedy of their creation in perpetuity. To view the monstrous tabloid process in Diana The Musical as anything but ironic is daft, dumb and blind.

The tabloid portrait of Diana is what the musical delivers, the glorious creation to please the masses and journalists. She was beautiful copy in all her forms, as was the monarchy, they pitted her against as her foe. But the production reveals that tabloids refused to take responsibility for their cause in her death. DiPietro and Bryan, in keeping with the phenomenon they criticize and expose (the public’s obsession with her, the press’ sensationalism which exacerbates it), never connect the paparazzi directly to her death. None of the actors dressed as paparazzi appear on stage at the conclusion, for she doesn’t die. Diana steps from flashing lights into the upstage darkness as the ensemble sings about her “lighting the world.” It is the image, her persona, that “lights the world,” as she lives forever immortalized in fictionalizations: movies, plays, TV series, etc.

In Diana The Musical it is the tabloid’s creatures we see as the well-publicized events of her life are made into hyperbole for public consumption. In the musical we witness her dating Prince Charles (Roe Hartrampf is wonderful as Charles in his development as the unmarried beleaguered, sometimes loving, then increasingly unhappy, angry, Diana nemesis), encouraged by Camilla (” Whatever Love Means Anyway”). Erin Davie is the perfect avatar for what we believe Camilla would be and do to keep Charles allured. She is a proper villain. There are enough jokes concerning her looks and strange sustainability with Charles as she bests Diana in his affections.

The tabloid’s cultural obsession with Diana’s looks, mien and beauty outshining the unfortunate looking Camilla is twitted throughout. The question floats over the relationship as the tabloids played up Diana’s beauty and Camilla’s ferocious mediocrity: how could Charles choose to be with Camilla and not Diana? Clearly, those are the manifestly superficial, shallow, cultural mores of tabloid journalism which value appearance over soul. They are not Prince Charles’ values.

DiPietro and Bryan take us through the Diana chronology, from the marriage (the quick change up of wedding dresses is excellent), the two children, Prince Charles being unable to give up Camilla as Diana must give up the dashing James Hewitt (Gareth Keegan). The crises mount until Diana voids her royal position by becoming a fashion icon who scandalously controls the media (the hysterical “The Dress”), as DiPietro and Bryan make their scathing critical ironies with facetious lyrics and buoyant music. It’s not all rock/pop upbeat cadence. Only the humorous, waggish songs retain the beat. Indeed, some of the harmonies are luscious (“If”).

Throughout, Charles’ relationship with Camilla holds, while Diana establishes a solid relationship with her maturing self, which grows apart from him, for he is a lost cause. Interestingly, the Queen editorializes about the overwhelming oppression of the monarchy in her own life (“An Officer’s Wife”), which Kaye sings affectingly in the song that identifies how the monarchy’s institutions changed Elizabeth’s relationship with Phillip. In her quasi empathy with Charles and Diana and Charles and Camilla, Judy Kaye’s rendition recalls a similar pathos expressed in The Crown. Only for duty did Elizabeth give up being the demure wife.

The tabloid wind-up dolls act exactly as we expect them to. And there’s even an over-the-top interjection by Barbara Cartland (Judy Kaye dressed in fluffy pink from top to toe). Cartland introduces us to James Hewitt as the instrument of vengeance in Diana’s life,”Here Comes James Hewitt.” Kaye as Cartland plies her influence on Diana and comments on Charles and Camilla’s affair, and Diana’s affair with Hewitt (“Him & Her, & Him & Her”).

Having Kaye do double duty as Queen Elizabeth and Barbara Cartland, both the head of empires in their own right, is brilliant and humorous. Kaye plays it off, enjoying the ironic joke. In the beginning of Act II Kaye gives the Queen’s tiara to the music conductor to hold as she switches roles. Cartland’s advice to Diana (a former romance fan), is that her novels are fantasy, romance is dead and in real life, men lie and cheat. The irony that an avatar of romance fiction warns the reigning fairy tale princess of the time that her prince is a cad is priceless.

Finally, the interjection of Andrew Morton (Nathan Lucrezio), who Diana “spills her guts” to (“The Words Came Pouring Out”), is an important addition in the evolution of Diana’s maturing persona, as she moves from under the oppression of the monarchy and gains her own revenge. From replicas of the royal’s iconic clothing (William Ivey Long), to the tell-tale hair (Paul Huntley), to the pat twists and turns in the Diana story, all unwind with irony and humor. Interestingly, the ravenous audience and the press are the butt of DiPietro’a and Bryan’s joke in addition to the royals. Indeed, no one escapes their ridicule, not even Cartland and Andrew Morton (Zach Adkins).

In keeping with the antic, amused and ironic perspective, many of the songs knock it out of the park. Kelly Devine’s choreography for the “Snap, Click” sinister twirling of the paparazzi around Diana with spinning movement, as they unspool their “tabloid tale” is excellent. It conveys the momentum of how storytelling gains a life of its own. The paparazzi and press become impassioned in their hunt for the prize statement, photo, revelation which they encourage then weave into Diana iconography.

“She Moves in the Most Modern Ways,” resounds with humor and cheek. It is sung by Kaye’s Queen, Davie’s Camilla, Holly Ann Butler as Sarah Spencer (Diana’s sister confidante), Hartrampf’s Charles, Andre Jordan as Colin and Anthony Murphy as Paul Burrell (who is also hysterical singing “The Dress” with De Waal, Kaye and the ensemble). The song codifies the press’s indictment of the monarchy as stuffily dead. Diana shaking things up is both a benefit and liability.

Of course, the theatricality Diana creates is marvelous copy. Throughout the production, Jeanna De Waal does not drop a stitch of the persona in the arc of the press’ vision of her. Her irony, sweetness, fury and flippant attitude beautifully captures the creatives’ vision. The song “This Is How Your People Dance” when Diana listens to Bach with Charles and the others, while imagining a rock concert with her favorites, where all but Camilla “shake it up” is riotous. From that point on it was clear to me what DiPietro and Bryan were about.

Finally, the creators emphasize the bare bone facts referenced by the media that, understanding what she was up against in her marriage, suffering without proper allies to rescue her, Diana Spencer carved out her own approach to her position in the royal corporation which had “winked at” Charles’ relationship with Camilla Parker Bowles. Growing into her own burgeoning identity, she empowered herself, using the media for great causes (the scene in the AIDS ward is poignantly done), that had not been taken up by anyone until she became involved.

Allegedly, for the royals, this was an embarrassingly mischievous and rebellious turn. To the media this was laudatory, though perhaps, self-serving. For Diana personally, we will never understand the mixture of altruism, concern and self-interest. Throughout, the press, not unlike with Marilyn Monroe, helped create her charismatic persona which to this day is hot copy. And it is that which Diana The Musical makes very clear with ironic twists that at bottom are an indictment of us all.

This is one to see if you remember that the tastelessness is all on the press and the public who clamored for the avatar Diana and the royals they received. Despite that underlying terrible truth, Diana The Musical expresses that message with humor, silliness, waggish irony and brilliance. Kudos to the creatives: David Zinn (scenic design), Natasha Katz (lighting design), Gareth Owen (sound design), the musical team and Ian Eisendrath (music arrangement and supervision). For tickets and times visit the website by CLICKING HERE.

LaChanze Stars in ‘Trouble in Mind’ Alice Childress’ Brilliant Play at American Airlines Theatre

Alice Childress finally receives a proper Broadway premiere in the Roundabout Theatre Company’s very humorous and profound production of Trouble in Mind, directed by Charles Randolph-Wright. Childress’ work, which stars an exceptional lead cast (LaChanze, Chuck Cooper, Michael Zegen, Brandon Michael Hall, Jessica Frances Dukes, Danielle Campbell), is a complex, sardonic and LOL play. It explores the cultural backdrops, impossible Civil Rights issues in the nation and their impact on the world of New York City theater in the 1950s.

The theatrical lens that Childress uses employs her own life experiences as an actress who never received roles which would allow her to express the full range of her talents onstage because of her skin color. Indeed, very few of the black theater actors were treated with the respect they deserved, tethered to the stereotypical roles that continued to foment institutional racism in the South and the North because such roles “comforted” the audiences and solidified the power structure.

It is to her credit and our great appreciation that Childress was a maverick who wrote Trouble in Mind (1955), that was well received off Broadway, but whose backers wanted major cuts and extrapolations before they brought it to Broadway to stem their fear of offending the largely white audience and hurting receipts. Rather than agree with having her artistic truthfulness destroyed to line the pockets of the producers, though it would further her career, Childress took a stand and pulled the play. Her actions present a beacon of courage for artists everywhere. Nevertheless, in refusing to compromise the themes, characters and indictments of the play against racism, she became a martyr for great theater art, and the work was excluded for 66 years from a Broadway presentation until this year.

Though others took up the cause and presented her play in various venues (it is being done in London), historically this incident indicates the dark clouds that hover over Broadway and theater to this day in issues of censorship, whether right or left, and the sub rosa, sometimes unspoken but understood restrictions placed upon artists and writers, whose works have great moment for our time, but who will never be given a hearing because of the gatekeepers and inherent power structure which shoots them down for whatever reason.

Trouble in Mind cleverly exposes this type of racist, sexist banishment and oppression with ridicule and ironic humor to powerful effect. The playwright reveals the hierarchy and dualism (controlled vs. controllers), of the theater world using a play within a play structure. The power structure is nullifying; there is no collaboration to make a better production. There is only the insistence in maintaining what is, killing artistry with repetition and dead, wooden characters, relationships and themes to pamper audiences.

Thus, in the name of entertainment, truth is sacrificed and the vital purpose of theater, to touch peoples’ lives and bring people together in a sense of community, is never fully realized. Indeed, Childress shows that such mediocre and superficial plays result in the wiping out of the true nature, identity, relationships and reactions of Black people historically in the US, depriving society of the spectacular contributions of a people and culture they refuse to acknowledge.

As the play opens Childress hints at this when experienced actress Wiletta Mayer (the incisive LaChance) shows the ropes to inexperienced John Nevins (the collected, often innocently funny Brandon Michael Hall), in how to deal with their director Al Manners (an ironic name if ever there was one). Michael Zegen portrays the increasingly stressed and unlikeable director, a difficult role, with nuance and fervency. Wiletta, with the help of veteran actors Sheldon Forrester (the inimitable and drop dead hysterical Chuck Cooper), and Millie Davis (the fine Jessica Frances Dukes), show John how to subtly “Yasss” the director, and second guess what he wants without being abrasive and obstructionist. For example, one inside joke is milked throughout the play: Wiletta tells John not to say he’s “inexperienced.” “Just tell him you were in Porgy and Bess as a child!” Since Childress prepped the audience for this joke, when it is reiterated to Manners, its double meaning is hysterical.

Schooling John in how to negotiate being black in white theater is superbly rendered by LaChanze, Cooper, Dukes and Hall to reveal the key themes of the play. Humor has helped blacks be incredibly resilient survivors as they continually dupe their “handlers” about what they really feel. On the other hand it has been soul killing to not be real and authentic. We understand this torment when Wiletta finally confronts the director with her truth because she is tired of the charade of “getting over” while subjugating herself and her identity. An elucidating irony reveals this is double indemnity. Such oppression is suicidal to whites as they push the racist line of the patriarchy to the point where such higher ups limit their artistic endeavors, achievements and bottom line for themselves.

How much more might theater be enriched if truthful revelations were embraced regarding all cultures and races? It would be life affirming and life changing. But the walking dead don’t know the difference. Instead, they refuse to be offended.

After Wiletta, Sheldon and Millie “educate” John in the black etiquette theater manual of how to be a success in the company of whites, he proves such a superior pupil in navigating the racist white attitudes, that he uses their knowledge against them, confused about his core self. As the audience is made knowledgeable about blacks’ dual identities, it realizes that it is being ridiculed with Childress’ brilliant set ups of humor. This is an indictment of the culture which “can’t handle” the reality that they are bigots and their racism must be coddled. The epitome of this sardonic thread is the truth that blacks are actually the polite, smart adults in “putting up with” whites’ necessary inhumanity of racism when, via projection, they are treated as children who don’t know much of anything. Who is duping whom in self-betrayal?

The playwright’s ironies are sage. Indeed, the audience, like the white controllers, is being “had,” if they think blacks enjoy oppression, insult and having their civil rights and humanity negated. A pure pleasure is how Childress presents all of these aforementioned themes and relates them to our culture today.

I find it interesting that the original producers were so worried that they actually had the “sensitivity” to realize that the play indicts the audience’s bigotry and racism. Or maybe they were upset at something else? Their own bigotry? The joke is wide-ranging, but the producers weren’t laughing, though the joke was on them, when Childress refused to change her work.

Act I is rife with the humor that the veteran actors, Sheldon, Millie and Wiletta set up to be mined throughout until in Act II, Wiletta has “had it.” The requisite subtle irony to soft peddle racism no longer appeals because she wants to be a great actress and the lies of bigotry are getting in the way. When Zegen’s Al Manners attempts to tell her how to be “natural” and not “think,” and that by thinking, she doesn’t “get” the character, LaChanze’s Wiletta boils with rage as he demeans her talent. And that anger spills over when she questions Manners about her character’s reactions in a scene when she is trying to protect her son from a lynch mob. The mother’s response and the son’s response is inauthentic, fake, and indeed, kowtows to white supremacists. The implication of her questions is clear.

When LaChanze’s Wiletta aptly confronts Zegen’s Manners about this, the explosion is inevitable. Manners walks away throwing the production in jeopardy and the other actors who need the money for the entire run are thrown into a tailspin. Trouble in Mind concludes in uncertainty. Though Wiletta took a stand confronting the director in the hope of evolving the play into an authentic rendering, only she is satisfied. For her it is worth it even if she destroys her career, which we understand by the end is meaningless if she, herself, can’t be who she really is. Childress ends with hope: Wiletta recites Psalm 133 to Henry (the excellent Simon Jones), as a spiritual petition and prayer for things to be better in the future.

Thus, we understand what happens if a black actor even dares to question the power structure represented by Manners; it’s potentially over. The play within a play ends but Wilette/Childress goes on. It is a prescient twist upon an ironic twist, considering that it took 66 years for the indictment of Broadway’s white power structure to finally be presented by the Roundabout with Trouble in Mind. What’s even more ironic is that the message still pertains.

To conclude. Last night, I sat next to an experienced actor and his wife, a Rutgers professor and casting director. Both affirmed that “getting a play produced” is the most difficult and heart-wrenching process in theater today. Childress indicates some of the reasons in her amazing work which targets racism, chauvinism, and sexism. Importantly, her timeless play’s themes relate to every “ism” that one might lay bare about human nature and oppression in the arts, especially by those who exploit creatives to gain the highest profits, while starving the artistic team, playwrights, actors. This has been especially egregious for those of color.

Sadly, this bigotry and discrimination is allegedly done for the sake of “entertainment.” The result is mediocrity and a fear of novel, original work. Instead, there is a steady repetition of old standby revivals or shows created from blockbuster films; there are few quality dramas or even musical productions. What has been sacrificed, is as Trouble in Mind reveals. Theater, the paramount live medium to touch lives. stir our humanity, bring community, and create a better society has been diminished. And there is no Tinker Bell to come along and revive it, thus far.

Trouble in Mind is a step in the right direction, however. Bravo to Roundabout to stage it.

Kudos to the additional actors who made this production sing with truth and humor. Alex Mickiewicz as Eddie Fenton and Don Stephenson as Bill O’Wray. Final shout outs go to Arnulfo Maldonado (set design), Emilio Sosa (costume design), Kathy A. Perkins (lighting design), Dan Moses Schreier (sound design) and the other creatives. You don’t want to miss the fine cast, Childress’ priceless, sharp wit and this long awaited Broadway premiere. For tickets and times go to their website CLICK HERE.

‘Caroline or Change’ the Roundabout Theatre Company Revival, Starring Sharon D Clarke

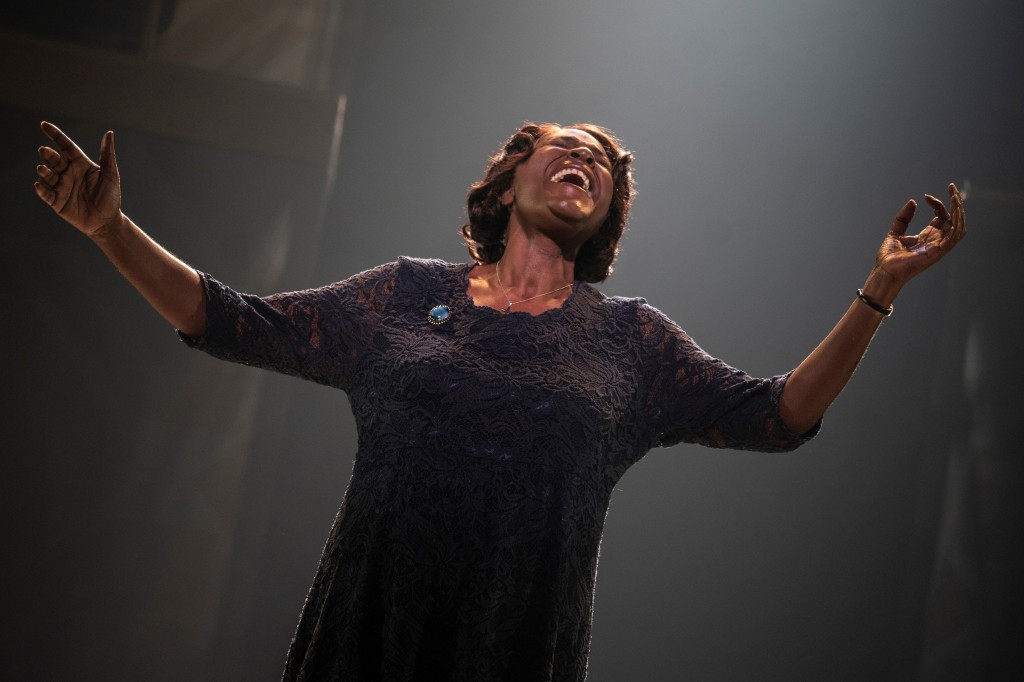

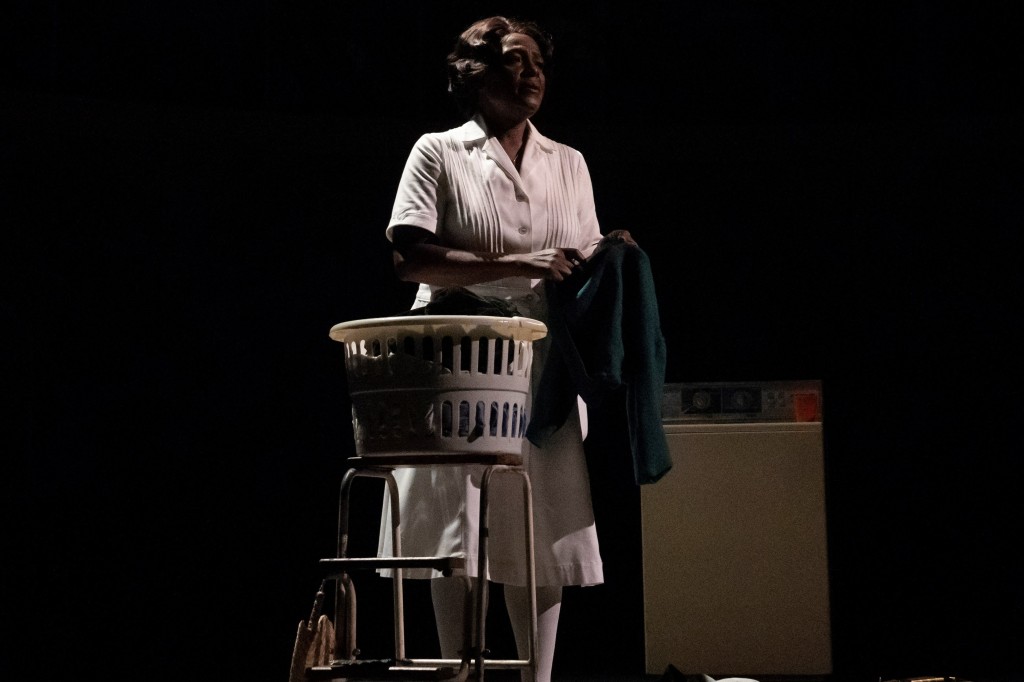

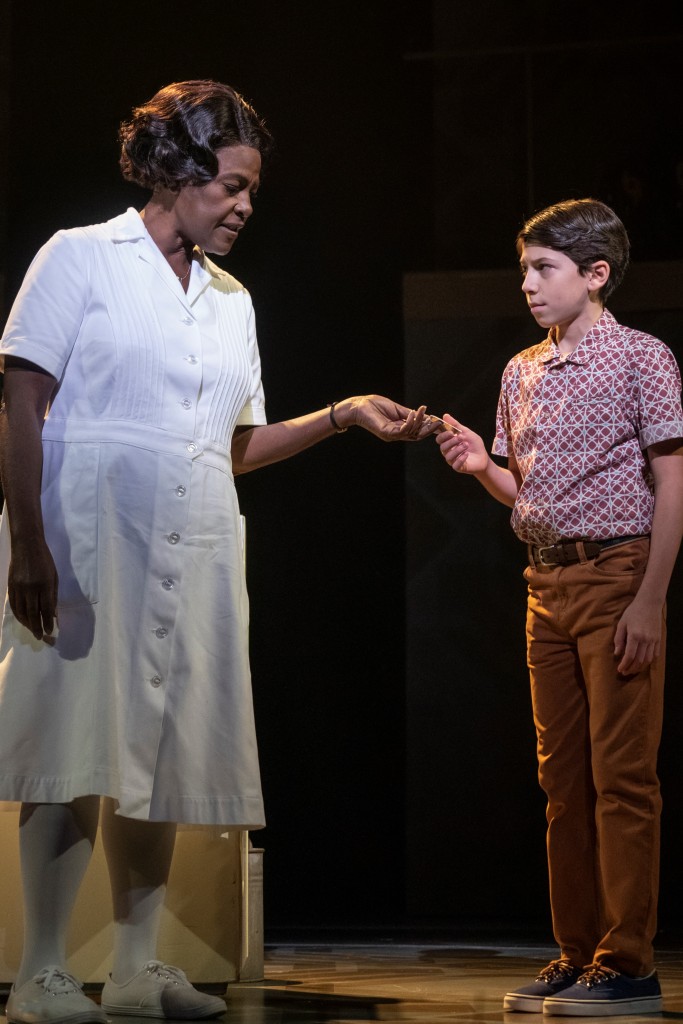

“Sixteen feet below sea level, torn tween the Devil and the muddy brown sea,” Caroline (the terrific Sharon D Clarke) characterizes her existence to herself in the musical revival Caroline, or Change at Studio 54. At the outset Caroline is in the basement doing the laundry for the Gellmans accompanied by the rhythms of The Washing Machine (Arica Jackson) and The Radio singers #1, #2, #3 (Nasia Thomas, NYA, Harper Miles). They are anthropomorphic representations of Caroline, along with The Dryer (Kevin S. McAllister) who makes the atmosphere as “hot as hell.”

Tony Kushner’s book and lyrics and Jeanine Tesori’s music bring to life a portrait of a black maid’s inner hell. She has no prospects of betterment to uplift herself out of the symbolic, oppressive swamps of white supremacist Lake Charles, Louisiana, 1963. Embittered, miserable, impoverished, on a minimum wage to support herself and three kids, she has lost hope waiting for goodness to come. She resents everyone, most of all “Caroline” who has created the situation she finds herself in, abandoned by her husband, single, a drudge at thirty-nine-years old.

While other blacks in the South become involved with the Civil Rights Movement and march against the brutality of Jim Crow, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, or seek an education, the exhausted Caroline can barely suffer herself through the next day’s labors cleaning and watching over the Gellman’s son, eight-year-old Noah (Jaden Myles Waldman the evening I saw it) who mourns his recently deceased mother. Her employers, Stuart Gellman (John Cariani) and Rose, his second wife (Caissie Levy) who attempts to be nice to Caroline, only make the situation worse.

Victims themselves of institutional racism, caught up in the discriminatory animus of the South, they can’t afford to raise Caroline’s wages. Nor do they relate to her on a personal level to uplift her, not that she would accept their attempts.

Indeed, throughout the play Caroline’s soul is metaphorically buried alive and/or drowning underwater as she struggles to pay for rent and food for herself and her children, one of whom is in Viet Nam. It is clear no one is coming to dig her out or rescue her, least of all herself. Unless a catalyst stirs her to resurrection, she will continue until the anger breaks out in violence against others; or she turns to self-destruction (acutely represented in a scene with Rose at the show’s turning point).

Interestingly, this horror of racism and its witting/unwitting adherents to a system that destroys is only made watchable through Tesori’s music, and Kushner’s poetic lyrics. Caroline’s anger and self-hatred projected out onto everyone, including friend Dotty Moffett (Tamike Lawrence) could have been a one-note agony of oppression and bondage. Key themes would have been undermined and occluded without the symbolism and majesty of the music and the fabulous voices that weave out Caroline’s story, of her inability to hope in an era when hope was the watchword of the Black South.

Tesori’s vibrant mix of 1950s-60s R & B/pop/soul/jazz/klezmer with a Diana Ross and The Supreme’s number at the finale and Kushner’s lyrics throughout measure like a soaring opera. They elevate the character of Caroline into an epic hero with her attendants, The Moon (the lovely voiced N’Kenge) and her children, especially Emmie (Samantha Williams) who has the spunk and courage to envision more for herself. Without our learning about Caroline’s emotional devastation embodied by the sonorous, operatic voices, Caroline or Change would have lost its vitality, currency and great moment, all of which are timeless and relatable to America 2021.

The superb cast is up for the challenge, singing beautifully, powerfully. Initially, it took me a while to understand the lyrics; the performers’ articulation wasn’t as acute as needed. However, like getting used to Shakespearean language, the heightened bond between the cast and the audience conveyed the centrality of Caroline’s conflicts. These become “a matter of ethics,” pride and dignity for her as a black woman who must carve out her identity in a bludgeoning, challenging racist society. What Kushner fashions as an issue of nickels and dimes evolves into the crux of black economic experience in the U.S, then and now.

Caroline’s dilemma is whether or not to take the change left in Noah’s pants pockets that he forgets to remove before Caroline does the laundry. Rose tells her to take it as a lesson for Noah to learn to “mind his money.” Caroline desperately needs the small bit of change, but also needs her soul to be intact. The minuscule handout becomes a symbolic gesture of Noah’s grandiose charity (in his view he believes Caroline and family appreciate his “largesse”). From Caroline’s perspective it symbolizes belittling crumbs of corruption taken from a “child,” making her an indigent, a beggar who cannot “rise above.” When she submits to temptation out of want for her children, she drains her dignity and faith in herself to “make it on her own,”

Of course, there would be no problem if the emotionally challenged Gellmans just provided a living wage instead of using money as a perverse lure for Caroline to damn herself. Caroline’s conflict symbolically parallels the perniciousness of economic inequality in America. It recalls demeaning public assistance handouts. Instead, if corporations paid the proportionate taxation rates, and with employers provided a decent, living wage, poverty, misery and an unequal justice system could be eradicated. However, the the US with its notorious history of enslavement (both white, black and colored) needs to demean souls to feed its own psychic sickness and keep the washing machine laboring by the underclasses to cleanse itself from its deranged filth.

This is just one of the themes Kushner reveals in a production luxurious with ironies and messages. Another controversy to look for is the dynamic between the Gellman’s situation and Caroline’s. The Gellmans are Jews who, too, experience discrimination and abuse as outsiders from the white supremacists that dominate the surrounding culture not only in the South but indeed, everywhere. Yet, there is little real empathy or understanding between Caroline and the Gellmans.

This humorously comes to the fore during the Chanukah celebration. Rose’s father, Mr. Stopnick (Chip Zien masterfully steals the moment) a Jew from New York City rails against Southern racism and hypocrisy. He uplifts the blacks’ position to foment violent revolution, which he suggests should have happened with the US Communist Party in the 1930s. Of course he is shushed up.

Meanwhile, his attitude about money which he delivers in a Marxist speech to Noah as he gives him Chanukah gelt is ironic. The twenty dollars ends up in Caroline’s “change cup.” Noah and she argue and afterward, Caroline realizes the fullness of the compromised, hateful individual she’s allowed herself to become. Sharon D. Clarke’s aria ‘Lot’s Wife’ is a showstopper. In the song Caroline’s conflict spills out in an epiphany. She concludes with a prayer to God, “Set me free; don’t let my sorrow make evil of me.”

Michael Longhurst’s direction of the ensemble is excellently dotted with interesting choices. The revolving platform is used symbolically. For example, during the Chanukah Party, Caroline, Dotty and daughter Emmie go in circles to please the Gellmans. Kudos enlightened staging by Fly Davis (set and costume design). Yet Caroline, et. al control; their servitude defines their strength. Without them, the Gellmans would be “on their own,” incapable, unable, weak. We are reminded of the South’s “need” of slavery rather than building a strong foundation from their own or paid labor which would have stultified their laziness and greed and encouraged a more prosperous economy and no need for a Civil War to end slavery, that peculiar “Christian” institution.

Kudos to the creative team: Jack Knowles (lighting) Paul Arditti (sound) Amanda Miller (hair and wigs) Sarah Cimino (make-up) Joseph Joubert (music direction) Nigel Lilley (music supervision) Ann Lee (choreography) who express Kushner’s themes roundly and provide a glistening backdrop (the swampland surrounding the house is wonderful) for the cast to play upon.

Caroline or Change opened in 2003 at The Public Theatre to mixed reviews, though it garnered awards. Sharon D Clarke starred as Caroline and won an Olivier for it in the London production in 2017. In the Roundabout production she reaffirms her grandeur, infusing her portrayal with substance, hitting her emotional peaks and turns with a resonant, anointed voice. This is one to see for the cast’s performances. If you missed it in 2003, don’t miss it in 2021. It is a reminder of what was and what is and a hope of what might be if we leave off divisive hatreds and rebirth ourselves to a better way. For tickets and times go to their website https://www.roundabouttheatre.org/get-tickets/2021-2022-season/caroline-or-change/

‘The Lehman Trilogy’ is a Triumph, Review

When you see Stefano Massini’s The Lehman Trilogy at the Nederlander Theatre, and you must because it is a majestic triumph which will win many awards and perhaps a Pulitzer, view it with an expansive perspective. Acutely directed by Sam Mendes, with a superb adaptation by Ben Power, the production’s themes highlight the best and worst of human attributes and American values. We see prescience and blindness, preternatural dreams and uncanny business acumen, along with unethical, unfettered capitalism and greed. If we are honest, we identify with this humanly drawn family, that hungers to be something in a new world that offers opportunity where the old world does not.

Humorously, poetically chronicling the Lehmans from their humble German immigrant beginnings, the brilliant Simon Russell Beale, (Henry Lehman), Adam Godley (Meyer Lehman), and Adrian Lester (Emanuel Lehman), channel the brothers, their wives, sons, grandsons, great grandsons, business partners and others with an incredible flare for irony and imagined similitude. Prodigiously, they unfold the Lehman brothers’ odyssey from “rags to riches” with a dynamism as fervent and ebullient as the brothers’ driving ambition which rose them to their Olympian glory in America.

The production is an amazing hybrid of dramatic intensity. It is an epic tone poem and heartbreaking American fairy-tale. It is a tragicomedy, a veritable operatic opus under Mendes’ guidance, Es Devlin’s fantastic, profound scenic design and Luke Halls’ directed, vital video design. Intriguingly, it remains engaging and edge-of-your-seat suspenseful through two intermissions and three hours. By the conclusion, you are exhausted with the joy, sorrow and profoundness of what you have witnessed. Just incredible! Three actors delivered the story of four generational lifetimes with resonance, care and extraordinary vibrancy. They are so anointed.

At certain moments the audience was silent, hushed, enthralled; no seals barked or coughed out of fear of disturbance. Perhaps this occurred because The Lehman Trilogy threads the history of antebellum America and the story of the most culturally complex, diverse and extreme (i.e. poverty and wealth), city on the globe, New York. Indeed, the audience watches transfixed by the magic of what “made in America” means, threading the poisoned soil of slavery to what “made in America” means today in an incredibly complicated and even more slavery poisoned institutionalization of economic corruption etherealized.

One of the subtle arcs of Massini’s and Powers’ Trilogy follows the growth of this corruption in one family as they expand their business. The brothers’ ambitious fervor morphs in each generation (the actors of the succeeding generation play the sons and grandchildren), until by the end, when Lehman Brothers is sold and divided up and sold again, when there are no more Lehmans involved in running an empire that still carries its name, we understand that outside forces and individuals have caused the interior dissolution via excess, greed and spiritual debauchery.

Especially powerful is the last segment of the Trilogy, “The Immortal.” After the second segment, “Fathers and Sons” concludes with the first and second suicide of the 1929 crash, the third segment continues with more suicides on that cataclysmic day as the debacle of selling goes on. And the segment ends in September 2008 a minute before the fateful phone call that no one is bailing out Lehman Brothers which becomes the sacrificial lamb that fails, while other firms are “too big to fail.” How American!

It is a keen irony that Lehman Brothers survives the 1929 crash. Indeed, they make it through the Civil War, WW I, the stock market crash and the great depression and WW II. Lehman Brothers is successful after the internet bubble burst and it moves steadily into the mortgage market mess in the 21st century until…it collapses. During the last Lehman generation, we watch how Bobby’s takeover and presidency shifts the perspective with regard to personal life and business; all is reform, even his religious observance. No longer do the Lehmans sit Shiva for the passing of a Lehman according to Talmudic Law; only three minutes of silence are allowed to recognize the passing of Bobby’s Dad, Phillip, before the business of Wall Street resumes in their offices.

Thus, by degrees, Lehman Brothers meets the future; the sun never sets on the huge investment bank with global centers everywhere which Bobby and his partners govern. The name becomes “immortalized,” even as Bobby symbolically dances into the future decades after his death. Adam Godley’s nimble movements are phenomenal in this dancing scene with the actors symbolically twisting Lehman Brothers into the success of the Water Street Trading Division and beyond. It’s hysterical and profound, a dance of ironic immortality which can’t last. No one thought Lehman Brothers could go bankrupt, but it is fated to. According to the brilliant themes and symbols (golden calf, golden goddess, tight rope walker), and ironies of Massini and Power, Lehman Brothers reaches its own apotheosis in the last moments of the production. Then the phone call comes and it’s over.

It is clear that after the last Lehman dies, others who take over (Peterson, Glucksman, Fuld), apply their own meretricious agenda on Lehman Brothers, defying good will and sound sense. Indeed, the entity that falls to its destruction is nothing like what Henry, Mayer and Emanuel and their progeny imagined or would have supported. Is this disingenuous? Massini, Powers, Mendes and the actors make an incredibly convincing case. Without the guiding influence of Judaic values and the mission that only the original family understood, Lehman Brothers is “Lehman” in name only. All of the meaning, value and venerable history have been sucked out of it.

Thus, is revealed the import of the conclusion. The once sound mission of Lehmans, under-girded by the values of the Talmud and Judaism is no more on the material plane. It exists in an infernal infamy, a cautionary tale of the ages. So it is fitting that in the last scene in the afterlife, one minute before that fateful phone call on September 15, 2008, Henry, Meyer and Emmanuel say Kaddish, a prayer for Lehman Brother’s demise. The dead bury the dead. Pure genius.

Massini’s/Power’s metaphors, Mendes and the actors understand and realize beautifully. They toss them off as so many luscious grains to feed off intellectually, if you like. Es Devlin’s revolving through history, glass house structure (just begging to have stones thrown at it), which the actors write on graffitizing the importance of Lehmans’ historical name-changing success is amazing. The turning platform and “see through” glass adds a profound conceptional component to the themes of money, power, finance and the energy of entrepreneurship. Luke Halls’ impactful video projections (the terrifying dream sequences, the burning Alabama cotton fields, the digital signals of the derivatives markets, etc.), enhance the actors’ storytelling with power. So do Jon Clark’s lighting design and Nick Powell’s sound design. Not to be overlooked Katrina Lindsay’s (costume design) and other creatives must be proud to have helped to effect this production’s greatness. They are Dominic Bilkey (co-sound design), Candida Caldicot (music director), Poly Bennett (movement).

There is more, but let peace be still and award The Lehman Trilogy sumptuously, all voting members of various organizations. It is just spectacular. For tickets and times go to their website: https://thelehmantrilogy.com/

‘Chicken & Biscuits’: Delicious Farcical Fare @ Circle in the Square

In this current time of COVID when our country faces daily crises of social disunity, dangerous political extremism, economic injustice and abdication of sound public health practices by craven Republican governors, Chicken & Biscuits written by Douglas Lyons, directed by Zhailon Levingston appears to lack currency on superficial inspection. Benign family squabbles, sibling rivalry, death and succession, a same-sex relationship, such subject matter at the heart of the play is quaint fare for a comedic entertainment that offends no one.

Except Chicken & Biscuits neither lacks currency nor is a quaint, “sitcom,” family comedy. Its levity and humor smacks of farce and satire with dead-on threads of truthfulness. However, if one is dreaming, much will slip past in the twinkling of an eye in this play about black culture, family and the foundations of faith that undergird the best hope for the black American experience in a racist culture that hovers invisibly and surfaces surreptitiously in Lyons’ one-liners.

The occasion is the funeral for the father of the Mabry family. He was the pastor of a Connecticut Pentecostal-type (there is a bit of dancing in the spirit) black church. Succeeding him in the position is Pastor Reginald (played with humor and oratorical fervor by Norm Lewis). The imposing, ambitious, dominant matriarch Baneatta (the funny Cleo King) whose resume would make any ignorant racist’s head spin, stands by his side in the church family.

Gathering with their parents are daughter and son: the accomplished Simone (Alana Raquel Bowers) and actor Kenny (Devere Rogers). Rounding out the family “going home” celebration are Baneatta’s hyper vivacious sister Beverly (the gloriously out there Ebony Marshall-Oliver) and Beverly’s enlightened, wise-cracking DJ daughter La ‘Trice Franklin (the buoyant Aigner Mizzelle). To spice up the explosive, sometimes irreverent proceedings are Kenny’s Jewish lover, Logan Leibowitz (the LOL Michael Urie) and mystery guest Brianna (sweet NaTasha Yvette Williams).

Before the guests arrive Reginald counsels Baneatta to relax and not become embroiled by family machinations. We note Baneatta’s stresses when she prays to God for patience in a humorous riff about her sister. During this preamble to the funeral service, others step in and out of the vestibule. They share their hysterical misgivings and woes about the family interactions to come.

The staging at the Circle in the Square is finely employed; the flexible set design by Lawrence E. Moten III and clever rearrangement of furniture and props serve as a church basement, sanctuary, nave and more. The modern stained glass windows and wood paneling upstage center, flanked by paintings of a black Jesus and crosses on both sides, serve to create the atmosphere of a thriving church. The underlying symbolism is superb as is the assertion of freedom from the typical forms of bondage Christianity.

Each family member, an ironic stereotype of themselves, identifies the complications that will arise as emotional storm clouds threaten on the horizon of the funeral and aftermath. Kenny attempts to soothe Logan who has been disrespected and largely ignored by Baneatta and Simone who cannot brook Kenny’s being gay, nor his attraction to a Jewish white man. When we see them in action with Logan, we note their austerity of warmth with mincing words and behaviors. As they watch him founder in blackland Christendom with two strikes against him, his whiteness and his gay Jewishness, he crumples instead of standing to and giving it back for fear of offense. These scenes are just hysterical and we see beyond to the strength and character of the individuals and their weaknesses.

As Logan, Urie’s ironic, humorous complaints to Kenny when they are alone, set up the tropes and jokes which follow as we watch how Baneatta and Simone treat him like a rare breed of exotic who must give obeisance. Hysterically, Kenny breezily abandons Logan to their clutches: it’s sink or swim time for Logan. Urie plays this to the hilt authentically, riotously with partners, King and Alana Raquel Bowers as the straight women who “bring it.” Watching this is both funny and upsetting. The women are intentionally clever. Their response is anything but Christian, loving and warm, but who is playing whom? We are reminded of the hypocrisy of evangelical churches to the LGBT community who engage in political Republican actions. Though this is a church in Connecticut and its members are most probably Democrats, the similar odor is clear. We wonder, can the situation evolve for the better? Can they achieve common ground?

The only one who accepts Logan with Christ’s unconditional love and hugs is Pastor Reginald. And Logan longingly remembers that Reginald’s Dad (who we discover to be a waggish, wild pastor) showed the same love. For Logan it is no small comfort, but apparently this open behavior was typical of the deceased pastor’s liberalism and Christian equanimity.

Obvious is the clash between lifestyles and personalities of the sisters: the educated achievement-oriented Baneatta, and the wild, flashily dressed, divorced and “out-there” Beverly and her DJ, hip, savvy, “ready for her social media celebrity” La ‘Trice. Mother and daughter counsel each other to “shut it,” projecting widely but not seeing their own faults and outrageousness to care to change. They do it because they are funny and they laugh at themselves. Do they have anything better to do being who they are? Marshall-Oliver and Mizzelle make for a great mother-daughter team.

Truly, the women dominate this world as the service, the sermon and eulogies get underway. Their behaviors and actions are at various proportions of farcical and funny as are all these typical, atypically drawn individuals.

Nevertheless, underlying the laughter and stealthy ridicule of each character being themselves, we get the importance of family and faith community. Despite the miry clay conflicts that emerge as part of the whirlwind of events that race through the play to the end revelation, these individuals have each other’s backs. And entry into the family, as Logan discovers, is not easily won. However, when it’s won, it’s forever.

The service is down-home (different from evangelical) with the hope of less hypocrisy via a more spiritual relationship with God. Thus, when the Pastor preaches in the spirit and dances a bit in the spirit, the audience even takes up the “Amens” in concordance. Indeed, the hope of a better way flows from Pastor Reginald’s fountain of faith. And by the conclusion of Chicken & Biscuits, a better way has been found in the dynamic of each of the family relationships, catalyzed by a mystery guest that Baneatta feared and kept secret for most of their lives.

Chicken & Biscuits serves on many levels. For those who enjoy a riotous comedy/farce with characters that tickle one’s funny bone continually, this is the perfect play. For those who enjoy being entertained, yet also enjoy the illumination that comes when thematic truths about life and people are cleverly revealed without preachy presentments, then this play surely delivers. For those who value the unity of family that never devolves to hatred, division, anger and bitter insult and rancor, the play is a portrait of a black family which resonates through the medium of satire and good will.

Kudos to Nikiya Mathis for her hair/wig and makeup designs: I loved her cool hair design for La ‘Trice, and Baneatta’s sober, contrasting hair and hat, to Beverly’s unsanctimonious hair and feathery headpiece. Simone’s hair design was just luscious. And additional kudos to Dede Ayite’s great, character revealing costume designs, Adam Honoré’s beautiful lighting design and Twi McCallum’s sound design. Their assistance was superb in making this a wonderful romp with circumspection if you divine it.

You need to see Chicken & Biscuits for the cast’s excellent ensemble work, Levingston’s direction and Lyons’ uproarious writing. In all its satiric humor about family “types,” the production took me away from divisive political rancor and stereotypes that follow. Chicken & Biscuits is a welcome joy. For tickets and times go to their website. https://chickenandbiscuitsbway.com/

‘SIX the Musical’ is Glorious Fun!

It took over 500 years for the six wives of Henry VIII to finally remix history and set the record straight, which they do nightly on Broadway in SIX the Musical at the Brooks Atkinson. What a phenomenal fun time to join these ex-wives in their exclusive club as they dish up the failed monarch, who is driven to upend the Catholic Church, lie, steal and kill in the name of gaining a male heir. We’ve had enough mansplaining about Henry’s actions. It’s time for the ladies!