Category Archives: Broadway

‘The Shark is Broken’ Three Men Missing a Shark, Broadway Review

Much of the real terror related to the film Jaws (1975), was experienced behind the scenes. The film was over budget $2 million and its flawed premise needed correction because the star of the picture, Bruce (the monster great white shark), was unworkable. To add insult to injury, director Steven Spielberg and the main cast were unproven at the box office and had issues to overcome. Finally, there was no finished script. For all intents and purposes, the film looked to go belly up, just like the three versions of mechanical Bruce, who foundered, sputtered and sank forcing the director and writer John Milieus into extensive rewrites.

However, Hollywood is the land of miracles. Jaws (adapted from Peter Benchley’s titular novel), broke all box office records for the time, despite the frankenfish never really “getting off the ground” the way Spielberg intended.

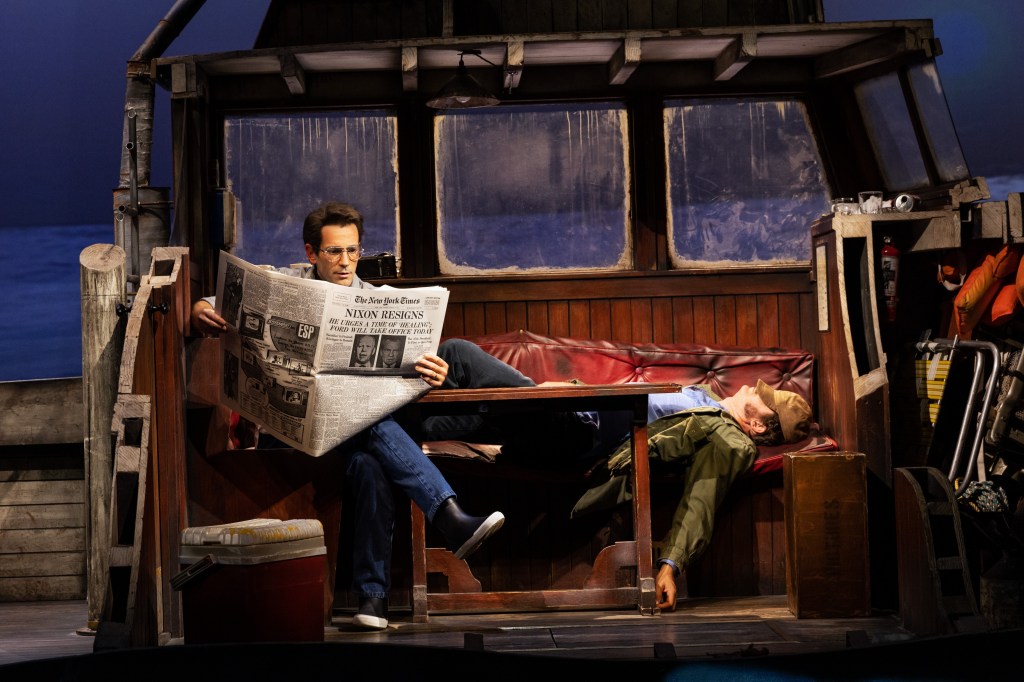

The Broadway show The Shark is Broken, currently sailing at the Golden Theatre until the 19th of November is the story of the three consummate actors behind the flop that might have been Jaws if Spielberg and his team didn’t rethink their broken monster, proving less screen time is more powerful when the shark finally shows up. The amusing play co-written by Ian Shaw (Robert Shaw’s son) and Joseph Nixon, and directed by Guy Masterson comes in at a slim 90 minutes. It features Alex Brightman (Beetlejuice the Musical) as Richard Dreyfuss, Colin Donnell (Almost Famous at The Old Globe) as Roy Scheider, and Ian Shaw (War Horse), who plays his father Robert Shaw.

The play focuses on these three actors who attempt to deal with the circumstances and each other as they try to make it through the tedious days waiting for Bruce, the real star, to “get his act together.” However, Bruce never does. Indeed, if one revisits the film, one must give praise to the superb performances of Dreyfuss, Scheider and Shaw who make the audience believe the shark is horrifically real and not a broken-down, mechanical “has been.”

Crucial to the film’s success are the dynamics among the actors which The Shark is Broken highlights with sardonic humor and a legendary sheen. Once the film skyrocketed to blockbuster status, the high-stress problems surrounding the film’s creation could be acknowledged with gallows humor. Such is the stuff that Ian Shaw and Joseph Nixon configure as they reveal intimate portraits of the actors’ personalities, foibles, desperations and bonding, while waiting for their “close-ups” with Bruce. Though the play appears “talky,” the tensions and undercurrents form the substance of what drives the actors. Like a shark that glides with fin above water, what lies inside each of the actors threatens to explode when least expected.

Even seemingly mild-mannered, emotionally tailored Scheider flips out. When his luxurious sun bathing is curtailed and his presence demanded on set, Donnell takes a bat and smashes it on the deck in fury. Donnell has no dialogue but his actions and body speak louder than words and we see how underneath that calm demeanor, Scheider is capable of potential violence which he keeps on a leash and, like a dog, gets it to heel when he wishes.

Based on Robert Shaw’s drinking diary, family archives, interviews and other Jaws‘ sources, Shaw and Nixon pen an encomium to the actors’ efforts and relationships forged during their claustrophobic time spent on the Orca, which floated on the open ocean east of Martha’s Vineyard between East Chop and Oak Bluffs. As the actor-characters arrive, we note the resemblances to their counterparts, further emphasized by their outfits, (costumes by Duncan Henderson), speech (dialect coach-Kate Wilson), and mannerisms.

Donnell is the fit, tanned, attractive, temperate Scheider, well cast to portray police chief Brody, head of the shark expedition. Brightman is the pudgy, scruffy, angst-filled Dreyfuss, who sounds and looks like the actor, and is filled with brio and insecurity as Ian’s Shaw batters his ego. As a dead-ringer, Ian portrays his father Robert Shaw, who merges the steely-eyed, gravely voiced, hard-drinking Quint with himself so the boundary between actor and character is seamless. Ian’s Shaw is comfortable in his cap and jacket ready to conquer his prey which includes the poorly written Indianapolis speech, and Richard Dreyfuss.

Thanks to the creative team, Duncan Henderson’s set and costume design, Campbell Young Associates wig design and construction, Jon Clark’s lighting design, Adam Cork’s sound design and original music, and Nina Dunn for Pixellux’s video design, the scenes when the three are on the Orca waiting for the great white to arrive include the manifested cross section of the boat interior, undulating ocean with seagulls flying overhead, wave washing sound effects, sunsets, and a lightening storm during which Ian’s Shaw stands rocking near the boat railing as he challenges the storm. The designated force of Robert Shaw comes through particularly, as he stands arms outstretched, back to the audience, accepting whatever the chaotic, dangerous elements unleash on him.

What do these men do to redeem the time as they wait for one of the three versions of Bruce to be commissioned to work? They do what sailors have done time immemorial: play innumerable card games, read the newspaper, play pub games and verbally and physically attack each other parlaying wit, wisdom, insults and choking. The latter occurs when Brightman’s Dreyfuss calls Shaw’s bluff about giving up drinking. With a quick maneuver, Dreyfuss takes Shaw’s bottle and tosses it over the side, a severe cruelty for a drinking man. Ian’s Shaw leaps into ferocity. It is only Scheider’s peacemaking and his threat that Shaw will be sued for delaying the film further, that remove Shaw’s ham hands from Dreyfuss’ quivering throat.

The feud between Dreyfuss and Shaw is exacerbated by inaction and the actors’ boredom between scene takes. This gives rise to the competitive hate/love emotions between the two men, which escalate during the play and are a fount of scathing, sardonic humor. When confronted about it, Shaw insists he is helping to improve Dreyfuss’ performance, and indeed, the tension between the actors behind the scenes travels well to their portrayals on film. The thrust and parrying of epithets and wit, which Scheider attempts to mitigate to no avail, forms the backbone of the dialogue which comes at the expense of Dreyfuss’ savaged ego.

Shaw, a noted writer and giant on the stage, sharpens his wordplay on Dreyfuss’ attempts at rebuttal. It is only after a quiet moment between Scheider and Shaw when Scheider tells Shaw how much Dreyfuss admires him, that Shaw lets up, but only a bit.

Son Ian is not shy about his father’s alcoholism and he plays the role as if he was familiar with how crusty and gritty his father could get when he was “three sheets to the wind.” Though he lost him at a young age and most probably doesn’t remember him all that well, the point is made that alcoholism and loss is generational. Robert Shaw shares that he lost his father to suicide when he was a youngster and always rued that he could never assure his dad that things would be all right. By that point his father had killed himself. Robert Shaw also died young and left his nine children wanting him. Thus, homage is paid by Ian to his grandfather and father who both battled alcoholism and died before their sons could really know them.

At its most revelatory, The Shark is Broken is about fathers and sons and how their father’s abandonment and/or rejection traumatized the actors who struggle to get out from under the sense of loss, rejection and insecurity. Dreyfuss shares that his father left the family and wanted him to be a doctor or lawyer. Scheider reveals his father disdained his acting career, until he eventually accepted it and became proud of his son. It is the few shared moments like these where the men bond and find common ground that are strongest and wonderfully acted. The play might have used more of these moments and fewer attempts at ironic jokes about how Jaws won’t be memorable in film history.

Shaw’s reductio ad absurdum of the future of films as a measure of sequels: sequels will beget sequels of sequels that have sequels rings true, of course. But the statement for humorous purposes is far from prescient.

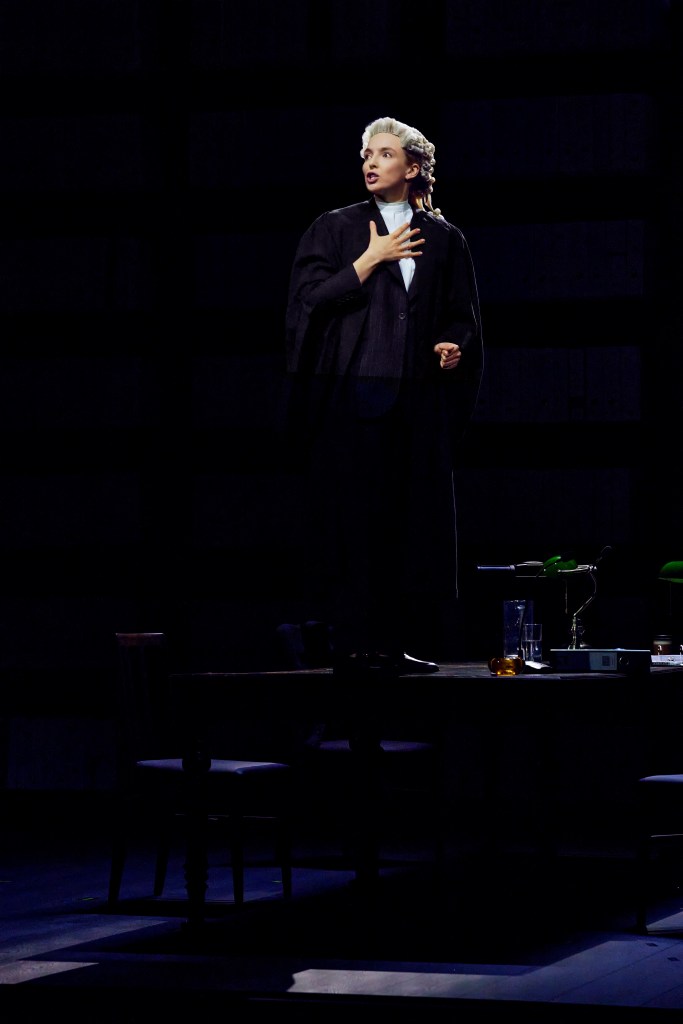

The Shark is Broken premiered in Brighton, England, went to a 2019 Edinburgh Festival Fringe run then opened on the West End before it arrived on Broadway. The play is humorous and entertaining with some missed opportunities for quiet, soulful moments. Certainly, those who have seen Jaws and its sequels will have fun and enjoy the near replica of the Orca and its inhabitants for a captured moment in film history made alive. The acting is crackerjack and Ian’s interpretation of the Indianapolis speech, which Shaw wrote himself, is at the heart of the film. As Ian delivers it, it is at the heart of the play and symbolically profound.

The Shark is Broken runs without an intermission at the Golden Theatre (252 West 45th Street). For tickets and times, go to their website https://thesharkisbroken.com/

‘Here Lies Love,’ The Stunning Bio-Pop-Musical Sounds Alarms About the Price of Democracy

The Millennium Club is the phenomenal, multi-level, theatrical setting of the bio-pop musical Here Lies Love. The resulting panorama is a monolith of disco and pop music, many-hued neon lights, black and white historical film clips, multiple dazzling screen projections, and spot-on performers’ heightened song and dance moves “here, there, everywhere” in living color. With 12 musicians (guitar, percussion, bass, etc.) some of the musical backing is prerecorded like karaoke, a cultural staple in Filipino lives. All this is the backdrop to David Byrne and Fatboy Slim’s spectacular immersive, sensorial, orgiac experience currently at the Broadway Theatre.

At the unfolding of the alluring dance party, the political and social history of 20th century democracy in the Philippines coalesce under a gleaming, disco ball. On the dance floor the pink, jump suited ushers shepherd and move the audience around a platform in the shape of a cross (a coincidental reference to the predominately Catholic country) that in a different configuration later becomes the bier upon which the coffin of the assassinated Ninoy Aquino moves leading the audience in the funeral procession.

On the second level, the jazzy, sun glass-wearing, cool, black-leather outfitted DJ (Moses Villarama) amps up the crowd, encouraging their investment in the show’s diversions. Throughout, the audience members in the balconies on three sides and on the first level dance floor, cheer, mourn, laugh and applaud. Their interactive roles as the captivated conspirator/citizens allow them to witness and participate in the iconic rise and fall of Ferdinand (Jose LLana) and Imelda (Arielle Jacobs) Marcos, celebrity leaders turned dictators.

With American encouragement and influence steeped in an autocratic colonial past, the Marcoses’ initially inspired governance devolved into a brutal, self-serving regime. Peacefully overthrown by the People’s Revolution (1986), after years of repressive, murderous authoritarianism, the Marcoses’ story masterfully stenciled by Byrne, Slim, Clint Ramos’ research and Alex Timber’s enlightened direction, is an important work for us in our time of QAnon, Donald Trump, the Federalist Society’s purchase of Supreme Court Justices, the Dobbs’ Decision and foreign donor’s dark money purchasing politicians, who, to feather their own agendas and dilute and destroy global democracies and the right of the people to self-governance.

The narrative of Here Lies Love is an encomium in song and dance. In its Broadway premiere ten years after its off-Broadway premiere at the Public (2013), the musical features Filipino producers and is brilliantly performed by an all-Filipino cast. With passion they portray the narcissistic Marcoses and their acolytes, who conspired to gradually hoodwink citizens to dance to the Marcoses’ siren songs.

Importantly, the production highlights the heroes. It is their vision for the Filipino people, and their hopes for a democratic country, that inspired them to risk their lives for the Filipinos’ right to “a place in the sun.” These courageous exposed and railed against the Marcoses’ excessive squandering of millions of dollars in a luxurious lifestyle, while a majority of deprived citizens had insufficient access to life-sustaining food, shelter, clean water and the freedom from military terror. This is the story of their love, and the sacrifice of their lives in the revelation of how easily leaders may fall prey to their own crass weaknesses and destroy a nation they disingenuously proclaim to love.

Key among the heroes is the liberal leader of the opposition party, Ninoy Aquino (Conrad Ricamora in an inspired and dynamic portrayal), and those aligned with Aquino like his mother Aurora Aquino (the wonderful Lea Salonga). Aquino’s persistent example, assassination by the Marcoses who were never held accountable, and subsequent martyrdom paved the way for the People’s Revolution.

Though the Marcoses are key players in the musical, Byrne and Slim make sure through quotes and commentary from interviews and news reports that praise does not go to the despots, one of whom is still attempting to exert power today through her son and president of the country. Here Lies Love is an object lesson in vanity, dereliction of duty, self-deception and treachery which Fatboy Slim and Byrne spin with irony in their lyrics in the title song, “Here Lies Love,” and in Imelda’s concluding song, “Why Don’t You Love Me?” written by Byrne and Tom Gandey.

Though the title of this production belies Imelda Marcos’ “love” for her country (she affirms her epitaph should read “here lies love”) Byrne, Fatboy Slim and director Alex Timbers underscore the hypocrisy of her love revealed in the musical’s arc of development. Her hypocrisy and velvet insidiousness are especially demonstrated in the 3,200 Filipinos killed, 30,000 tortured and disappeared and 70,000 imprisoned (the numbers are higher most probably).

These statistics are listed in the surrounding projections in black and white. The musical uplifts the Filipino people’s resilience, courage and love of their countrymen and women. The citizens are a shining example for democracies around the world and for whom the musical’s title really applies. Indeed, the Filipinos’ love is demonstrated in the People’s Revolution at the conclusion, and culminates memorably in the final poignant song.

The production is majestic and profound. Its themes counsel that citizens of democracies must be sentinels against those like the Marcoses, who would exploit democratic elections, usurp power, declare martial law, and order the military to protect the powers of the executive, while disbanding all the other branches of government. By silencing their critics and killing opponents, dictators like the Marcoses rebrand terrorism as law enforcement in order to steal from the treasury and maintain their hold on power. This follows after smearing the opposition, jailing perceived enemies without due process, nullifying democratic laws and wiping out a free and fair press, who cannot call out their crimes.

All of these egregious actions Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos did while the United States turned its head and looked away.

Thus, as the audience dances and follows the guidance of the ushers and DJ, they are initially blinded and mesmerized by the fantastic surreality of beauty, fun and energy. And as Imelda the beauty queen ends her relationship to Nimoy Aquino and takes up with Ferdinand on a publicized 11 day whirlwind romance that ends in a white wedding, we watch as she morphs from the naive country girl to the savvy doyen of American fashion and celebrity. The “steel butterfly” (a nickname given to her by the press), has become a clever political animal, who is a help meet to ruthless Ferdinand right before our eyes.

The 90 minute dance party summarizes the Filipino seduction and decades of growing repression in key events. After their marriage, Imelda is overwhelmed by being in the limelight and has a nervous breakdown, requiring therapy and becoming addicted to drugs. Jacobs portrays the changes in Imelda convincingly. When she sings “Walk Like a Woman,” we realize that the once innocent girl has become a seductively calculating political creature as she tirelessly campaigns with her husband and helps him win the presidency. She becomes knowledgeable about culture and obsessed with the construction of buildings (The Philippine Cultural Center), which draw attention to herself as a celebrity but do nothing for Filipino citizens.

The projections and black and white film clips from archives are salient in revealing the glittering Marcoses rise. Byrne’s lyrics are from interview quotes and reports covering the Marcoses and Aquino. Photographs show Imelda with everyone from Andy Warhol to various leaders like Ford and later Reagan,, who propped up the Marcoses and gave them sanctuary in Hawaii after they fled during the People’s Revolution. Ricamora’s Aquino gives rousing speeches about Imelda’s egregious use of funds for a cultural center (“The Fabulous One/I’m a Rise Up”) which sets the audience/citizens on edge and alerts them to financial corruption in the Marcos’ regime every time Aquino calls them out. Byrne creates lyrics that borrow heavily from his speeches.

The turning point comes after Marcos’ scandal with American actress Dovie Beams, whose impact on Imelda is ironically highlighted in a dance number with multiple “Dovie Beams” in black bikinis and blonde wigs. The original tape recording between Beams and Marcos is played during this point in the production accompanied by music and lights reinforcing the spectacle. Imelda considers that “Men Will Do Anything” (Jasmine Forsberg is Imelda’s powerful inner voice).

Losing trust in Ferdinand, she conveniently latches onto self-deception and sings of her dream that she is the people’s star and slave (“Your Star & Slave”). As she disingenuously commits herself to her country, Ferdinand, licking his wounds in embarrassment, retires to the hospital with Lupus and attempts to win Imelda back. Jacobs and Llana’s duet “Poor Me,” is a beautiful example of a couple lying to each other, complicit in keeping their hold on power.

The beating of students protesting the Marcoses’ corruptions, Estrella’s (the heartfelt Melody Butiu) revelations of Imelda’s lies about her heritage (“Solano Avenue”) and Estrella’s subsequent arrest and punishment for going to the press, puts the Marcoses’ maladministration on everyone’s radar. Aquino speaks for the masses in his criticism of Imelda, which she and Ferdinand not only ignore, but feel victimized by. The easy way dictators shift blame and beat their breasts about being persecuted is highlighted by Byrne’s song and incredibly acted by Llana and Jacobs. One almost believes they are victims and the unjust criticism is weaponized by Aquino, protesting students and opponents.

After bombs go off in Miranda Plaza wiping out almost all the liberal party, Marcos blames it on the liberals (1984 fascist logic-why would they intentionally kill themselves) and declares martial law in Order 1081. Byrne and Fatboy Slim have outdone themselves in the lyrics and forceful, pounding music that codifies the new dictatorship and power grab by the Marcoses. During the performance of “Order 1081,” the statistics enumerate the casualties of the Marcoses’ punishments for for protests. Ninoy Aquino is jailed for 7 years. There are no trials, just guilt and oppression. The staging and performances are shocking and disturbing.

We ask, what? Are the glorious Marcoses murderers? Indeed. And they act privileged and justified in brooking all “nefarious” opposition.

After seven years when the jailed Aquino needs a heart operation, the Marcoses send him and his family to America on the stipulation that he never return. Aquino doesn’t keep his promise to the criminal dictators. Instead, he sacrifices his life, an assassinated martyr, which is another shocking blow in the musical slammed into the audience’s psyche with all the force of lights, sound effects and music that explode when the audience least expects it. And in the aftermath with Salonga’s song as Aquino’s mother, the crowds at his funeral effected by the ushers and the coffin on the platform are staged with impeccable emotional poignance.

Timbers reveals how the Peaceful Revolution happens in the staging and the surrounding projections. We understand that the crowds demand Marcos’ resignation after a rigged election in which he proclaimed himself the winner. The people’s massive protests demand the Marcoses resign. Ronald Reagan gives his friends sanctuary in Hawaii, announced via projections of New York Times’ headlines. It’s an appalling closure to the Reagan administration’s supporting dictators and murderers who deny culpability.

Ironically, in the musical it’s a blip that passes speedily which Byrne intentions because he is sardonically indicting the Americans for supporting dictators as a horror of colonialism’s aftereffects. Also, it is incredibly current and an expose of the Republican MO to protect their own. They conveniently pardoned Nixon’s criminality during Watergate and refuse to censure or disqualify Donald Trump as a presidential candidate indicted for his crimes against the country.

The last song “God Draw’s Straight” (But With Crooked Lines) is a testament that democracy depends upon the power of the citizens worthy to govern themselves. The song is magnificent, encouraging and a reminder that citizens must actively resist the lies, excesses and dereliction of corrupt, dangerous leaders, by continually calling them down in peaceful protests.

From the top of the dance party whose song “American Troglodyte” incriminates the Marcoses’ chief influencer, the crass, monopolistic, corporate consumerism of America, to “God Draw’s Straight” (But With Crooked Lines), this gobsmacking production chronicles how the Marcoses, emblematic of how dictator-murderers, subvert democracies and rise themselves up through lies, misinformation, disinformation, propaganda, self-victimization and the vitiation of constitutional government in exchange for military oppression and terrorism. Of course, the dictators justify their crimes with the “poor me” ploy, the refusal to admit responsibility and martial law directed to empower and protect them.

Every American citizen should see this incredible work of art whose creative team worked overtime to meld all the technologies and elements to effect Timbers,’ Byrne, and Slim’s (with additional music by Tom Gandey & Jose Luis Pardo) vision. The performers are incredible, invested, determined to express this vital story that must be told.

Special recognition goes to Annie-B Parson’s choreography, Clint Ramos versatile and quick change costume design (referencing the times according to news articles and video clips), Justin Townsend’s lighting design, M.L. Dogg & Cody Spencer’s well-balanced sound design (not any easy feat with such a venue), Peter Nigrini’s wonderful projection design, Craig Franklin Miller’s spot-on hair design and Suki Tsujimoto’s make-up design. Additional kudos goes to J. Oconer Navarro (music director), Kimberly Grigsby and Justin Levine (vocal arrangement), Matt Stine and Justin Levine (music production & additional arrangements).

I’ve said enough. For tickets and times go to their website https://www.telecharge.com/Broadway/Here-Lies-Love/Ticket

Photos by Billy Bustamante, Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman (2023)

‘Grey House,’ a Subtle Send-up of Horror Films, That Delivers With Humor and Surprise, Starring the Fabulous Laurie Metcalf

Top shelf performances and eerie effects in lighting, sound, and on-point set design carry Levi Holloway’s horror-thriller Grey House through to its unreasoned, macabre and opaque ending, leaving the audience disturbed and unsettled in an unusual, visceral entertainment. The production, currently running at the Lyceum Theatre until September 3rd, is insightfully directed by Joe Mantello for maximum preternatural weirdness and warped grotesqueness that is also a send-up of the genre.

With sardonic humor and glimpses of the supernatural which evanesce in the twinkling of an eye, the playwright Levi Holloway shrouds the action along a path of darkness, confusion and sometime shock, until the widening road dead ends in a climax and (spoiler-alert) Max’s partner Henry vanishes, replaced by a new guest as Raleigh (Laurie Metcalf), bags packed, leaves.

Spoiler alert! Stop reading if you want to be surprised by the play. Read the rest if you are looking for clues to guide you down the dark road of Grey House.

Where and how Henry de-materializes doesn’t matter. We have witnessed his sadistic torture by a child tormentor and watched astounded at his masochistic enjoyment of pain. When he contributes his substance to create a palliative “alcoholic” drink that anesthetizes, most probably for a future unrepentant male, our fog of understanding clears a bit. Henry receives well-deserved punishment for his unspeakable past acts, that, until he entered Grey House, have gone unanswered. Is the function of this house and these female inhabitants to deliver justice? If so, married couple Max (Tatiana Maslany) and Henry (Paul Sparks) who seek help at Grey House after a car accident are “innocents” walking into a trap.

The creaking, groaning, hellish, two-story, ramshackle abode in the mountains, referred to as “Grey House,” initially appears to Max and Henry as a welcome, cozy shelter from the blizzard and their injuries. However, we know better and not just because of the advertising campaign for the show.

Previously, we have been introduced to the strange, uncanny children of the mountain cabin and their mother/caretaker Raleigh (the sensational Laurie Metcalf). Two of the “sisters” initially raise the spirits in a representative song of the region, singing a cappella. They produce an effect which is haunting and spooky. At turning points throughout the production, a total of four songs are sung: two authored by Mountain Man and the others by Bobby Gentry and Sylvan Esso. Each song is more compelling and meaningful in relation to the action, thanks to Or Matias (music supervisor and a cappella arranger).

Henry’s ironic comment that he’s seen this movie before and they “won’t make it,” lands with humor, horror and truth. We know something he doesn’t. He and Max must stay away from the two unnatural malevolents, a Wednesday Addams meme, Marlow, and her frightful companion in wickedness, the vicious, hell-bound Squirrel. In the initial moments of dialogue and action, they are daunting.

Throughout the action, both could double cast as witches in their sarcasm, sinister intentions and sub rosa text delivered in a straight-forward manner, as they allow the “words to convey the meanings.” The import of their statements are clues to what is really going on, however, the substance is easily missed because the audience is Holloway’s prey and is misdirected as she steers them down the road, and blinds them with her dark shadows of uncertainty.

Nothing is directly expressed. Of course, Henry and Max have the bulk of their interactions with these vixens, who rule the roost and who, Raleigh, their ersatz mom, calls “willful creatures,” an understatement.

As the Wednesday Adams meme who is a self-satisfied, self-admitted, proud “bitch” in the MAGA vein of “owning the libs,” Sophia Anne Caruso is terrific at suggesting the horror underneath the action. She enjoys making her guests, especially Max, feel creeped out.

Squirrel, whose damaging persona is represented by her name and her having chewed the phone chord so no calls come in or go out, is the youngest. Portrayed with insinuation and sadism in a nuanced performance of softness and brutality, Colby Kipnes is superb. She is the youthful doppleganger of The Ancient (Cyndi Coyne) and is the instrument of revenge holding “everyman” predator Hank to account in a twisted time reversal. For unspeakable acts he committed decades before, the young Squirrel and the others collaborate in effecting physical retribution which the anesthetized Henry willingly accepts as his due.

“Grey House” exists beyond time and place, the repository of the wounded in life who exist when we meet them as otherworldly beings or some other undetermined construct of humanity, which the playwright ironically leaves in the realm of uncertainty. When we meet this particular brood, Raleigh suggests others will come and go, as she in fact leaves at the conclusion with a packed suitcase, letting Max who may be a younger version of herself replace her as the caretaker.

The bottles of “moonshine” the ersatz family of women, including A1656 (the fine Alyssa Emily Marvin), and hearing-impaired Bernie (Millicent Simmonds passionately completes the witches’ coven) extract from male predators is kept refrigerated for the next visitor destined to arrive at Grey House. Like Henry he will be punished to sustain its prosperity and existence as a “living thing.”

Laurie Metcalf’s Raleigh is continually surprising in a spot-on, gorgeous performance as the hapless “mom,” who she portrays with power, insight and presence. Of all of the actors, Metcalf is the most surreal yet authentic and empathetic, as we feel for what she goes through at Grey House, though we don’t succinctly understand what we see happening before our eyes. When she is on stage, she is imminently watchable. Her lead, as subtle as it is, guides Caruso’s Marlow and Kipnes’ Squirrel to their understated ferocity which spills out in their insightment to get Henry to masochistically “fall on his own sword,” as they act out their vengeance.

Sparks’ Henry is so likable and loving in his relationship with Maslany’s Max who is the perfect wife, that we are shocked that both are not who they appear to be, Henry less so than Max. Maslany shows a sense of humor with the girls, then turns, flexing her emotional range when she expresses the appropriate terror knowing their luck has changed and she confronts evil. Sparks’ demeanor during the ordeals he is put through is nuanced. His confession is forthright and shocking in its understated delivery.

The silent characters, The Boy (Eamon Patrick O’Connell), and The Ancient (Cyndi Coyne), are vital in their gestures and presence. They add to the dynamic of “the family,” and Coyne’s Ancient is the wounded mirror image of Colby Kipnes’ Squirrel as a youth.

The production is amazing in its confabulation of mystery and opaque unreality delivered by the creative team. These include Scott Pask’s wonderful set design, Rudy Mance’s subtle costume design, Natasha Katz’s stark, atmospheric lighting design, Tom Gibbons’ house humanizing sound design, Katie Gell & Robert Pickens’ wig and hair design, Christina Grant’s makeup design. All of the actors are invested, as is Mantello in relating the otherworldly and arcane side by side with the profane, teasing out humanity in its wild derivations.

In life we see “through a glass darkly.” We receive glimpses beyond what we assume to be “reality” but know there is more that is present. What our senses apprehend, continually deceives us, though we like to believe “we know” and we are in control.

Holloway reminds us of the contradictions, the ironies, the shades of life that have no clear explanation. Indeed, the hints she drops about how the “family” of “willful creatures” operates in this spooky place are never solidified. All is intimation. The “moonshine” as Raleigh refers to it, “sold during the summer,” Marlow names “The Nectar of Dead Men,” which seems a more accurate handle by the conclusion. The duality of symbols existing on a spiritual, preternatural level are contrasted with the profane, material realm, for example when Max makes eggs (they are real-made offstage), for the “hungry, always hungry” sisters-daughters-creatures.

Thus, all is not what it seems. Holloway drives this theme home using the horror-thriller genre conveyance as a grand joke to prod us toward fear and laughter. She sends up that genre and twits us about our nightmares displayed in horror films, mirroring those found in our unconscious in dreams.

The development of the story and its characters, who are timeless archetypes reflected in literature (the good, the evil, the furies who gain vengeance), drive this work beyond genre. Thus, in an attempt to nail down Grey House and dismiss it, one may lose the deeper levels of Holloway’s symbols and complex, convoluted themes. One fascinating example is the red tapestry woven of the sinews of the historical predators, who have come to visit the cabin and whose “Nectar of Dead Men” is distilled for future use. The labels on the jars in the refrigerator tell the tale. The men’s remains we learn are in the walls, the grounds or in the basement which Squirrel frequents.

In Grey House Holloway’s vision expressed by Mantello and his creative team and enacted by the wonderful ensemble is a tonal hybrid of humor, a teasing send up of horror-thrillers, yet terrifying in its deeper representation of the patriarchy which doesn’t come off looking well in its tapestry of innards and crimes committed with impunity finally answered with rough justice, by “willful creatures.” The play is highly conceptual and may bear seeing twice because you will definitely miss connecting elements. Or just enjoy the ride and the fabulous acting and theatricality which will not disappoint.

For tickets and times go to their website https://greyhousebroadway.com/

‘The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window,’ Lorraine Hansberry’s Mastery of Ideas in a Superb Production

Oscar Isaac’s Sidney Brustein in Lorraine Hansberry’s most ambitious play, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window (directed by Anne Kauffman) never catches a break. Hansberry’s everyman layman’s intellectual is in pursuit of expressing his creative genius and achieving exploits he can be proud of. When we meet him at the top of Hansberry’s masterpiece, which is full of sardonic wisdom, sage philosophy and political realism, Sidney is a flop looking for a reprieve. This revival, first produced on Broadway in 1964, was tightened for this Broadway revival (one noticeable end sequence with Gloria was shaved, not to the play’s betterment). Currently running at the James Earl Jones Theatre with one intermission, the production boasts the same stellar cast in its transfer from its sold out run at BAM’s Harvey Theatre in Brooklyn. The production is in a limited run, ending in July.

It is to the producers’ credit that they risked bringing the play to a Broadway audience, who may not be used to the complications, the numerous thematic threads, the actualized brilliance of unique characterizations and their interrelationships, and Hansberry’s overall indictment of the culture and society. Sign is a companion piece to her award-winning Raisin in the Sun. It explores the root causes why the Younger family is where it is socially and economically. Vitally, it examines the political underpinnings of institutional oppression and discrimination via reform movements, symbolized by the efforts of Brustein and friends who promote the reform candidacy of Wally O’Hara.

To focus her indictment of the perniciousness of political and social oppression, Hansberry examines the vanguard of reformists, Greenwich Village artists, activists and journalists who are emotionally/philosophically ready to make social/economic change of the type that the Younger family in Raisin in the Sun yearns for. However, these Greenwich Village mavericks are the least equipped tactically to sidestep co-optation and the political cynicism of the power-brokers. They realize too late that the money men will fight them to the death to maintain a status quo which inevitably destroys the vulnerable and keeps families like the Youngers and drug addict Willie Johnson struggling to survive.

The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window is timeless in its themes and its characterizations. When we measure it in light of current social trends, it is fitting that the play transcends the history of the 1960s in its prescience and reveals political tropes we experience today. Additionally, it suggests how far society has declined to the point where cultural and political co-optation (a principal theme) have been institutionalized via media that skews the truth unwittingly. The result is that large swaths of our nation remain oblivious to their exploitation and dehumanization, ignorant that they are the pawns of political parties, who promise reform then deliver regression. In short they, like Sidney Brustein and his friends, are seduced to hope in a better world that reform politicians say they will deliver. But when they win, through a plurality of votes from a diverse population, they renege on their promises and continue to do what their “owners” want, which is to “screw” the little people and deprive them of power and a “place at the table.”

Hansberry’s setting of Greenwich Village is specifically selected as one of the hottest, most forward-thinking, “happening” areas in the nation. Brustein’s apartment is the focal point where we meet representative types of those found in sociopolitical/cultural reform movements. His community of friends are activists who believe their friend and candidate Wally O’Hara (Andy Grotelueschen), is positioned to overturn the Village’s entrenched “political machine.” Sidney, reeling from his bankrupted club, which characterized his cultural/intellectual ethos (idealistically named Walden Pond after Henry David Thoreau’s book), purchases a flagging newspaper (The Village Crier) to once again indulge his passion for creative expression. He does this unbeknownst to his wife Iris (Rachel Brosnahan), a budding second-wave feminist who waitresses to support them financially. She chafes at her five-year marriage to Sidney, shaking off his definitions and the identities he places on her, one of which is his “Mountain Girl.”

Activist and theoretical Communist (separated from the genocidal Stalinist despotism) Alton (Julian De Niro), drops in with O’Hara to encourage Sidney to join the crusade to elect O’Hara with the Crier’s endorsement. Sidney declaims their persuasive rhetoric and assures them that he will never get involved in political activism again. However, as events progress, his attitude changes. We note his friends, including artist illustrator Max (Raphael Nash Thompson), stir him to support O’Hara with his excellent articles. Sidney, mocked by Iris about his failures, is swept up in the campaign. When he hangs a large sign in his window that endorses O’Hara, his adherence to push a win for the “champion of the people” increases in fervency.

The sign symbolizes his hope and his seduction into the world of misguided activism, but its meaning changes over the course of the play. Hansberry doesn’t reveal the exact moment that Sidney decides to take up the “losing cause” after he disavowed it. However, his fickle nature and passion to be enmeshed in something “significant” with his friends helps to sway him.

In the first acts of the play, Hansberry introduces us to the players and reveals the depth of her characterizations as each of the characters widens their arc of development by the conclusion. We note the development of Mavis (Miriam Silverman), Iris’ uptown, bourgeois, housewife sister, who is married to a prosperous husband and is raising two sons. We also meet David Ragin (Glenn Fitzgerald), the Brustein’s gay, nihilistic, absurdist playwright friend, who lives in the apartment above theirs and is on the verge of success. Both Mavis and David, like Sidney’s other friends, twit him about Walden Pond’s failure. Mavis and Iris are antithetical in values and Mavis views her sister and brother-in-law as Bohemian specimens to be observed and secretly derided as entertainment. We discover Mavis’ bigotry when she opposes the union of their sister Gloria (Gus Birney), a high class call girl, to Alton, the young light-skinned Black friend.

The genius of this work is in Hansberry’s dialogue and the intricacies of the characterizations. It is as if Hansberry spins them like tops and enjoys the trajectory she creates for them, which ultimately is surprising and sensitively drawn. Organically driven by their own desires, we follow Sidney and Iris’ family machinations, pegged against the backdrop of a political campaign that could redefine each of their lives so that they could better fulfill their dreams and purpose. However, the campaign never rises to the sanctity of what a true democratic, civic, body politic should be. Indeed, the political system has been usurped in a surreptitious coup that the canny voter “pawns” are clueless about.

Tragically, instead of political power being used to combat the destructive forces Hansberry outlines, some of which are discrimination, drugs, law-enforcement corruption, economic inequity and other issues that impact the Brustein’s and their friends’ lives, O’Hara and his handlers have other plans. But first, they cleverly convince the voters a win is unlikely and they pump them up to believe in the possibility of an O’Hara success that would be earth-shattering and revolutionary. This, we discover later, is a canard. The “revolutionary coup” can never occur because the political hacks control everything, including Sidney’s paper which they exploit to foment support for O’Hara. How Hansberry gradually reveals this process and ties it in with the relationships-between Iris and Sidney, Alton and Gloria, Iris and Mavis and the other friends-is a fabric woven moment by moment through incredible dialogue that pops with quips, peasant philosophy, seasoned wisdom, and brilliant moments that evanesce all too quickly.

By the conclusion, the solidity of the characters’ hopes we’ve seen in the beginning have been dashed to fold in on themselves. Both Iris and Sidney learn to reevaluate their relationship with each other and their misapplication of self-actualization, which allowed a tragedy to happen. Likewise, Alton’s inflexibility about his own approach to his place in an exclusionary, oppressive culture ends up contributing to a tragedy that might have been prevented. In one way or another, these characters particularly, along with David’s self-absorbed nihilism, contribute to Gloria’s death.

Symbolically, Hansberry points out that love and concern for other human beings is paramount. Too often, relatives, friends and cultural influences contribute to daily tragedies because human nature’s weaknesses in “missing the signs” contort such love and service to others. Ironically, politics, whose idealized mission should be to reform and make the culture more humane, decent and caring, is often hijacked by the powerful for their own agendas to produce money and more power and control. The resulting misery and every day tragedies accumulate until there is recognition, and the fight begins to overcome the malevolent, retrograde forces that O’Hara and his cronies represent.

This, Sidney vows to do with his paper and Iris’ help in a powerful speech to O’Hara proclaiming a key theme. To be alive and not spiritually, soulfully dead, one must be against the O’Haras of the world and the forces of corruption. To support them is to support death and dead things. To recognize how the power-brokers peddle death, one must discern their lies and avoid being lured into their desperate cycle of destruction, which they control to keep the populace oppressed, hopeless and suicidal.

The actors’ ensemble work is superior. Both Isaac and Brosnahan set each other off with authenticity. Miriam Silverman as Mavis hits all the ironies of the self-deprecating housewife, who has suppressed her own tragedies to carry on. And Julian De Niro’s speech about why he cannot love or marry Gloria is a powerhouse of cold, calculating, but wounded rationality. Hansberry has crafted complex, nuanced human beings and the actors have filled their shoes to effect their emotional core in a moving, insightful production that startles and awakens.

The play must be seen for its actors, direction, and the coherent artistic team, which perfectly effects the director’s vision for this production. These artists include dots (scenic design), Brenda Abbandandolo (costume design), John Torres (lighting design), Bray Poor (sound design), and Leah Loukas (hair & wig design).

This must-see production runs under three hours. For tickets and times go to their website https://thesignonbroadway.com/

‘New York, New York’ is a Wow, Manhattanhenge is Here.

Inspired by the titular MGM motion picture written by Earl M. Rauch, the musical New York, New York at the St. James Theatre is an ambitious, updated adaptation from uneven source material. Its spectacular production values guided by the prodigious five-time Tony winner, Susan Stroman, who does double duty with direction and choreography, is set over the course of one year with the four seasons structuring the arc of development in the lives of the characters who want to “be a part of it in old New York,” from the Summer of 1946 through the Summer of 1947. Written by David Thompson, co-written by Sharon Washington with additional lyrics by Lin-Manuel Miranda and music and lyrics by John Kander and Fred Ebb, New York, New York’s music differs from that featured in the titular 1977 Martin Scorsese film.

The noted exceptions are a few songs like “Happy Endings” and two schazam hits sung by Liza Minnelli in the film. Minnelli was initially associated with “New York, New York,” until Liza told Uncle Frank it was his to sing. Afterward, it became a part of every concert, TV show or gig Sinatra starred in. “But The World Goes ‘Round” is singularly Minnelli’s, though others have picked it up and run with it applying their own versions.

With such song classics, the production doesn’t capitalize on their tonal motifs threading intermittently from Act I to Act II more than just once. Instead, saving the best for last, they explode toward the conclusion. At the end Jimmy Doyle’s band (the real orchestra) rises up from the pit, playing “New York, New York” with bravado and glory. By far, the two songs are the richest, most seismic and memorable of the score. Despite who is singing them, they are a pleasure because of their symbolic associations.

The first is New York City’s anthem played as an encouragement around every dooms day disaster the city experienced in recent memory from the Terrorist Attack of 9/11 to the COVID-19 botch job by the twice-impeached former president, when nightly the city came out to applaud healthcare workers and some played Sinatra recordings of the signature song from their balconies. The other lush beauty about the irrevocability of life’s changing turns, highs and lows, is a classic best remembered for Minnelli’s fabulously impassioned rendition.

These songs, in their own right, are like the North Star. “But the World Goes ‘Round” appears to guide the writers to effect a richer, stirring musical about making it in a tough, unforgiving town which necessitates growing a thick skin because regardless, the world will spin, whether one plays the broken-hearted victim as Jimmy Doyle does initially in Act I, or become the heroes of their own myths as do all the characters who serendipitously meet in a Booking agent’s office, then join Doyle to play in a “tired club” in Act II in a reviving number “San Juan Supper Club.” However, reaching success takes a while.

Specifically, the book meanders as it strikes out into different story-lines of immigrants and ethnics, who come to Manhattan to establish their unique voices and become the stars of tomorrow. Problematically, the music, which should lead in a brassy, bold pop style of the latter forties reimagined, follows without the same consequence and heft of the two signature songs we long to hear that show up in full force by the end. The story lines take wayward side directions, straying away from “the heart of it,” making Act I (17 songs) much longer than necessary to spin the characters’ struggles in New York. The central focus becomes redirected. Eventually, it comes back and the lens crystallizes on salient themes, before flitting away to feature another plot-line.

The centrality, which is supposed to be how Jimmy Doyle’s Major Chord Club and musical group comes together, is delayed by scenes of the violinist from Poland and Mrs. Veltri waiting for her solider son to come home. What is represented is the loss and death from the war, a loss which explains why Doyle drinks, is angry and argumentative with those who could help him. He grieves his talented brother dying, while he, the inferior with “flat feet,” serving unheroically behind a desk, feels guilt as the ghostly shadow of his glorious sibling occludes him.

The impact of grieving New Yorkers out from under a cataclysm of the holocaust, which took violinist Alex Mann’s family and the heroic sons of America’s war dead is important, but diluted in the mix of all that is going on. Doyle, Mann (Oliver Prose) and Mrs. Veltri (Emily Skinner) are meant to carry that theme of loss and grieving as one more aspect of the “city that never sleeps,” but the power fades too fast for the audience to fully appreciate it, as the action springs to another scene and character. This is the nature of the city which acknowledges then moves on with forward momentum.

Not all the story-lines need specific scenes for explication. Some either should have been edited to a stark jabbing point with the songs either pumped up and primed, or eliminated. They seem extraneous, done for the sake of inclusiveness, rather than out of a visceral, organic need driving the characters in their forward momentum. Editing might have slimmed down the excess that sometimes dissolves the production’s vitality. Though the writers moved away from the film’s story, to be inclusive and representative in an update, they do feature the relationship between multi-talented musician Doyle (Colton Ryan really picks it up in Act II) and powerhouse singer Francine Evans (Anna Uzele has the creditable voice).

However, the idea of a New York City, where inclusiveness and freedom, born out of anonymity and size, that also has a down side, is not manifested with unique particularity beyond the concepts of struggle and making it. Only Jimmy Doyle’s character is nuanced and shaded with interest to reveal a convincing transformation that is believable, effected beautifully by Colton Ryan.

Despite these problems with the book, Stroman leaps over them creating terrific moments in representing the lifestyle of New York City street scenes. She materializes a pageantry of perfection in staging the dance numbers with delightful framing assists from Borwitt’s scenic design and Billington’s lighting design. These gloriously drive the production, along with the fabulous projection design by Christopher Ash and Beowulf Boritt, which majestically integrates historical photographic blow-ups with the sets (scaffolding erected to look like apartment buildings). New York City in their vision is a treasure to behold back in the day, as they remind us of how we got from then to now. Of course, the heartbreaking projections of the old Pennsylvania Station torn down in contrast with Grand Central Station which we are eternally grateful for Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s crusade to save it, are vital historical references in an ever changing Manhattan.

Stroman choreographs the ensemble with excitement, energy and vibrance. She shepherds the musical’s technical team to strike it hot. They create the atmosphere and stylized beauty of post war New York neighborhoods, synchronizing the scenic design, lighting design and projection design. Along with Donna Zakowska’s stunningly hued costumes pegged to the period, Michael Clifton’s period makeup design, Sabana Majeed’s hair and wig design and Kai Harada’s sound design (I heard every word) these talents manifest Stroman’s concepts of a bustling, charged city hyped up to establish the nation’s new-found prominence after winning WW II in Europe and the Pacific. The city of dreams is once more collecting its dreamers who will sink or swim according to luck and perseverance.

There are many moments in New York, New York I loved. The song “Wine and Peaches,” performed with the ensemble’s tap dance on a foundational iron beam, beautifully set “high in the sky” with the city projected from down below during the ironworkers lunchtime is gobsmacking. It’s a remembrance of the iconic black and white photo of the Empire State Building being erected and ironworkers sitting on the structural beams over 80 + stories up. The song is emblematic of New York City construction workers who are brave, balanced and accustomed to such heights, that they might dance “for the hell of it.” It is also a testament of the tremendous development in the city whose air rights allow buildings to rise taller and taller. Symbolically, visually and musically performed with grace and fun, the number is one of the most memorable and brilliant.

Another moment that is thematically important is the song “Major Chord,” as Jimmy Doyle and friend Tommy Caggiano (Clyde Alves, a fine song and dance man) discuss that “music, money and love” combined in a harmonious chord become what drives a purposeful life for them. In the lead up praise of the city, Tommy’s humorous truism rings clear for New Yorkers when he says, “It’s the greatest social experiment. Everybody lives here and everybody’s natural enemy lives here. And we manage not to kill each other. For the most part.”

To top his comments as New Yorkers are wont to do, Jimmy says, for him, New York City is a “major chord,” and Uzele’s Francine joins in to ask how to find her major chord (music, money, love). Tommy and Jimmy help her find an apartment near Jimmy to start her journey to become a star. Eventually, as fate throws Francine and Jimmy together (more through events he causes) they marry, have ups and downs and reconcile at the “Major Chord,” Jimmy’s successful club which concludes the musical with a resounding and stupendously staged “New York, New York,” sung by Uzele’s Francine.

In Act I, “New York in the Rain” is beautifully sung and staged with colorfully hued umbrellas skipping across the stage, under their own power, and others held by the ensemble who twirl them in uniformity with graceful energy. As Jimmy, Ryan’s “Can You Hear Me?” and “Marry Me,” are appropriately winsome and romantic as Act I concludes with Francine and Jimmy’s relationship sealed in love and marriage.

Act II picks up the forward momentum. Jimmy pushes for his “major chord” in his relationship with Francine, “Along Comes Love” and in the dynamic “San Juan Supper Club” (Ryan, Angel Sigala, John Clay III) which is a rousing, dance number where the musicians we’ve met in Act I come together to form Jimmy’s band which will headline his club Major Chord. In the superb “Quiet Thing,” Ryan’s Doyle shares the preciousness of arriving at his dream, not with great fanfare, but with the inner knowledge of its success, which is the confidence that the dream is the reality. The lyrics and music are Kander and Ebb at their finest, and Ryan delivers a superb, heartfelt slam dunk that any artist can identify with.

As Francine understands that the villain with a smile, Gordon Kendrick (Ben Davis), wants to unrealistically take her, a black woman, out on the road so he can sexually seduce her, Francine affirms what her husband Doyle has told her all along. Kendrick is a hypocritical wolf in a “promoter’s clothing.” She concludes her last song on the radio after Kendrick tells her “she’s finished.” “But the World Goes ‘Round” is Uzele’s home run and Francine’s realization that she must move away from him and join Jimmy at the Major Chord Club.

An incredible and breathtaking encomium to New York City is in one of the final musical numbers “Light” presented by Jesse (John Clay III) and the ensemble. Kudos go to the technical team and Stroman to effect Manhattanhenge through the projections, sets and lighting. It is absolutely magnificent and of course, symbolic that light, love and musical goodness can be in a city that is its own memorial to industry, dreams and aspirations.

Manhattanhenge occurs when the sunset perfectly lines up with the east-west streets on the main street grid in Manhattan. It’s Stonehenge in NYC! Happening twice over a two-day period, on one day you can see the sun in full and on the other day you get a partial view of the sun. Then to encapsulate the “light” in the city that is its own monument, Francine concludes accompanied by Jimmy Doyle’s band with “New York, New York.” And indeed, the show ends in a major chord at Doyle’s Major Chord Club in a beautiful flourish with Uzele singing her heart out as the audience stands with applause dunning the critics who panned the production.

New York, New York is exuberant, complex and bears seeing twice. There is so much happening you’re going to miss something and think the fault is in the production, as I did initially. Stroman is her representative genius. If one goes without expectation, your enjoyment will be immense. Look for the fine performances. Colton Ryan is sensitive and heartfelt especially in Act II and his gradual transformation is exceptional in “Quiet Thing,” and afterward. There’s nothing like knowing one is a success and at home in that confidence. The principals, especially Uzele, Janet Dacal, Ben Davis, Angel Sigala and the others mentioned above have golden voices. All are their own major chords, thanks to the music supervision and arrangements by Sam Davis.

For tickets and times go to the production’s website https://newyorknewyorkbroadway.com/

‘Good Night, Oscar’ Sean Hayes in a Marvelous Must-See

It is not that Sean Hayes looks like Oscar Levant (he is taller), or speaks like Levant (not really), or accurately displays Levant’s neurotic ticks and eye blinks (he ticks away), or imitates his posture (he slumps, cutting off 2 inches of his own height). What Hayes does nail is Levant’s pacing, deadpan delivery, comedic sentience and his self-effacing, desperate, sorrowful heart. And it is these latter Levantesque authenticities that Hayes so integrates into his being that when he shines them forth, we believe and follow Hayes wherever he takes us during the brilliant, imminently clever Good Night, Oscar, currently running at the Belasco Theatre with no intermission.

With a well-honed, drop-dead gorgeous book by Doug Wright (I Am My Own Wife), and superb production values (Rachel Hauck-scenic design), (Emilio Sosa-costume design), (Carolina Ortiz Herrera & Ben Stanton-lighting design), (Andre Pluess-sound design), and J. Jared Janas for hair & wig design, director Lisa Peterson’s vision brings us back to 1958 in NBC Studios’ inner sanctum, where the backstage drama is more incredible than what happens on live camera. Of course, by the time Hayes’ Levant appears live on The Tonight Show, we, Parr (Ben Rappaport), June Levant (Emily Bergl), Alvin Finney (Marchánt Davis) and head of NBC Bob Sarnoff (Peter Grosz), have lived two lifetimes fearing the worst. After all, this is live television with no splicing tape or editing. Whatever happens is. And that makes the tension and thrill of this production that duplicates the fear of “live,” (just like on Broadway, but with no extended rehearsals), just smashing.

Doug Wright acutely, craftily ups the ante of danger in the 80% probability that Levant will make a mess of things. Perhaps, he won’t make it to the studios, just like the time he left an audience of three thousand waiting in fancy dress to hear him play the piano, concert style, which was popular in those days. Then, he let them wait and never showed up.

Levant is noted for his version of the stellar George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.” Parr and the TV audience expect Levant to play it, but of late, he is hesitant and may refuse and walk off the set. So Levant might be on time but blow-up his appearance, as he has done before, saying the extraordinary and surprising, if asked to comment on religion, politics or sex. Furthermore, he is plagued by the spirit of Gershwin and has reveries of the past where, at times, he makes no sense. So much can go wrong, like Murphy’s Law states: “If something can go wrong, it will.” With Levant this has become a truism with scheduled bookings and appearances.

As Grosz’s apoplectic Sarnoff and Rappaport’s reasoned Parr go head to head about the high-risks they are taking because they cannot fail during “sweeps week,” we discover that recently, Levant is completely unreliable and “out there.” Sarnoff refers to him as a “freak.” On the other hand Parr has specifically chosen Levant because he needs his new Burbank show to be a success. Levant always delivers because Parr knows his close friend and can set him up for the best one-liners and witticisms in the business.

With Levant, Jack hopes to compete his way into prime time with a low budget and the talk show format he has perfected. It is a difficult task because he is on every evening, is rather high-brow, and the network underestimates him. However, Rappaport’s Parr believes Levant is a “true original,” who “treats chit chat with all the daring, all the danger of a high-wire act.” Parr knows that he will score with Levant because his unexpected brilliance lands his one liners all the time. Jack will start the engine, and Levant will speed off with the cues for a perfect show, nose diving into space and leveling off every time. He only needs to show up and get in make-up. Wright has created the set up for anticipation so that when Levant arrives, if he does, we are ready for his prime time antics, which happen behind the cameras.

That Parr doesn’t convince Sarnoff to calm down remains a problem. Sarnoff tells Parr he has booked “chica chica boom boom” Spanish musician and band leader Xavier Cugat as Levant’s replacement. He will save the day if Levant stiffs The Tonight Show, like he stiffed The Eddie Fisher Show the week before. In other words, as Levant keeps the studio waiting, the greater the likelihood that Levant’s career is down the toilet, along with the bad will that Parr has contributed making his goal to be in prime time a pipe-dream.

The issues appear to be settled when June Levant, Oscar’s wife, sweeps through the doors in her period piece, flowery outfit looking chic and composed. Parr is relieved until June tells him that she committed Oscar, and he’s in an asylum because she finally had enough. Parr becomes as apoplectic as Sarnoff and the rest of the play spins out of control, is brought back into control, then goes up into the high-wire act Parr wished for, after Levant shows up and fills everyone with expectation and sometime dread that he will blunder irreparably and destroy all they’ve planned.

To add to the tension, right before Levant goes on the air, he downs a bottle of Demerol and seems comatose. The saving grace is that Levant is a drug addict and his body is accustomed to so many drugs of his choosing, he has to take a bottle of it to stop his hand from shaking. (I reminded you of that, if you question how taking that many pills and functioning is possible. Think functioning alcoholic.)

Who is this drug addict? Who is Jack Parr? In what century are we? One of the salient take-a ways of Good Night, Oscar is its reverential nod to the Golden Age of Television, when culture, wit, superior comedy shows and superb programs (I Love Lucy, Playhouse 90, Your Show of Shows, What’s My Line, etc.), and actual bona fide news graced the air waves. Jack Parr was one of the first hosts of The Tonight Show franchise, which has lasted to this day and has been duplicated many times over in other shows on other channels.

Then, Parr made individuals famous during his five-year stint. One of his frequent guests was comedic concert pianist and Hollywood celebrity Oscar Levant. Thanks to Doug Wright’s incredible, stylized portrayal of Levant, and Sean Hayes’ remarkable ability to don the ethos of the exceptional pianist and tortured artist, we understand his emotional underpinnings. And we empathize with the psychological whirlwinds captivating Hayes’ Levant. Figuratively haunted by George Gershwin’s shadow, Levant glorifies in and also regrets riding Gershwin’s coattails to celebrity. Wright fancifully manifests this haunting by materializing Gershwin, who cajoles, persuades and torments Hayes’ Levant with remembrances of his greatness and serene notes of “Rhapsody in Blue.” Davis’ Alvin tells Parr assistant Max (Alex Wyse) that these babblings are auditory and visual hallucinations.Max should just “go with it.”

After June Levant and Parr tell Hayes’ Levant he must play, that the concert grand is waiting, Levant goes head to head with Gershwin’s ghost. Portrayed by John Zdrojeski, we note Gershwin’s arrogance and dapper, mordant, ghostly looks. However materially insubstantial he is, to Levant, the only one who sees him, he is beautiful and elegant. We understand that compared to Gershwin, Levant is a midget in looks and talent (in his own flawed estimation). Levant has undermined himself becoming Gershwin’s fawning adherent. Thus, eventually Levant obeys his hallucinations, as the Gershwin ghost compels him. Will Hayes’ Levant be able to play anything with arthritic hands and twenty-five concentrated doses of Demerol in pill form churning around in his stomach?

There is no spoiler alert. How Levant, his body hungering for drugs, manages to manipulate Parr assistant Max and his own nurse assistant Alvin to get what he wants is frightening, funny and ironic. Wright employs Max and Alvin as devices to reveal Levant’s backstory and acquaint the audience with his former grandiloquence, while we take in his deteriorating condition. Levant, Judy Garland and other celebrities shared the same fate with the pills and drugs that the studio doctors offered. Ironically, the tragedy of Oscar Levant and his glory and folly, which Hayes portrays with perfection, has great currency for our time.

Though Levant’s story is a throwback to that crueler, exploitive time of the studios, where the industry ground up artists in its maw and left them at the side of the road to deal with their own damage, we see the effects of big pharma today, expanding their client base beyond celebrities to the US public. Additionally, we note that corporations have become even more insidious than the Hollywood studio system as exploiters of writers and other artists. Good Night, Oscar is vital in showing how the then parallels the now.

Wright, Peterson and importantly, Hayes, elucidate how artists were encouraged to destroy themselves gradually for the sake of their “careers.” That Parr and June Levant are similar in their persuasions, pushing Oscar to “entertain,” is answered by the fact that Oscar adores being in front of an audience, even if it’s only for the four hours he has been “sprung” from the asylum. However, his self-harm becomes irrevocable as celebrity self-destruction through addictions to drugs and alcohol, unless redeemed is irrevocable in our time as well.

Wright’s play is an encomium to Levant’s genius, his humanity and his artistry, beautifully shepherded by Peterson and the creatives who convey her vision. And Sean Hayes’ performance is one for the ages.

There are gaps in this review for the sake of surprising the reader. Most assuredly, Good Night, Oscar is a must-see. You should go a few times to appreciate the wit, humor and spot-on performances, all of which are superb. Sean Hayes is especially poignant and authentic. For tickets and times go to their website https://goodnightoscar.com/

‘Summer, 1976’ Laura Linney and Jessica Hecht are Terrific

Summer, 1976 at the Manhattan Theatre Club’s Samuel J. Friedman Theatre is predominately two solo performances with a few dynamic interchanges, the principal one occurring at the conclusion. The static, expository “play,” directed by Daniel Sullivan, occurs in the minds and reflections of Diane (Laura Linney) and Alice (Jessica Hecht). Through their discourse, we learn how they established a close friendship over a summer which gradually fades into memories when Diane moves away a few years later. If not for the brilliant, authentic performances by Linney and Hecht, and the enlightened direction by Sullivan, one might think that “the dramatic event” that supposedly initiates the conflict never occurs. Nor does the conflict occur manifestly. However, the performances and direction overcome the lack of theatricality, and make Summer, 1976 interesting enough thematically to put this on one’s radar to see.

One of the key themes that playwright David Auburn (Proof) explores in Summer, 1976, is how the right connections, though brief in the span of a lifetime, may vitally change one’s development and help individuals evolve in a direction they might never have taken without such influence. Diane and Alice become friends who, for no particular reason, share their memories revealing this thematic point in this stylized storytelling that alternates back and forth from Diane and Alice as each reflects and remembers. Through their perspectives as reliable/unreliable narrators, they discuss themselves and each other, sometimes offering conflicting details, leaving us to decide for ourselves who is the more accurate storyteller, if it even matters. During the course of their reveries, we note there are more similarities than differences between them, if we carefully tease out the deeper levels in their personalities.

Superficially, Diane has an immaculate house and is a foodie, with some quirky lapses in her perfection. Interestingly, she is unconventional in one regard. She carelessly becomes pregnant having a fling with a man who wasn’t “all that,” and who she dismisses from her life so she can raise her daughter alone. She doesn’t give much thought that Gretchen might need a father, but is confident within herself not to be desperate for a man at her side. which would cause more stress and complication. Besides, Diane has enough inherited money to raise her without worries and continue with a quasi-serious art career which Alice encourages.

Alice points out that Diane’s work reminds her of Paul Klee’s. Diane confesses that she used to be influenced by Klee, but has moved on. Diane never finishes her art pieces, a revelation which Diane eventually confides to us and discusses with Alice. For her part Alice doesn’t think Diane’s art is very good, precisely because they are unfinished. We learn this through Alice’s commentary after Diane makes various disclosures.

Alice contrasts with Diane. Her housekeeping is messy. None of the furniture matches and she isn’t a foodie or an excellent chef as Diane is. Also, Alice is a laid back housewife who helps husband Doug, He doesn’t make much money as a college professor and their lifestyle reveals it. In those days women could still live (not comfortably) on one salary. Doug and Alice manage, though Diane notes that they don’t have style, class or much dynamism. Ironically, staying at home doesn’t encourage Alice to be a superior housewife or foodie. What she does all day is take care of her daughter and Doug, read and clean up the house as best as possible, when it moves her .

These superficial differences would stand in the way of their becoming best friends, if their daughters were not thrown together at the beginning of the summer. Because their daughters adore one another and beg Diane and Alice for play dates, the mothers reluctantly get together to please Gretchen and Holly. It is during these hot days of summer, Diane and Alice move beyond the surface to reveal deeper elements about themselves and their circumstances to forge a beneficial relationship.

Auburn uses narration and the women’s solo reveries to reveal their lives. However, it is the nuanced performances and portrayals by Linney and Hecht that elevate this play and make us interested in these two women, who live unadventurous outer lives. The actors land on the humor of their confessions and judgmental criticism (only given to the audience) about each other. It is only when the women take day trips, the first to an antique store where Diane buys Alice a Bauhaus desk, that their relationship takes off. Afterward, we note that there is a soulful simpatico that they seem to have with each other that transcends their differences.

That soulfulness is brought to the fore during two crucial events that Linney’s Diane and Hecht’s Alice reflect upon. During one summer day Diane has a wicked migraine. Alice lovingly nurtures her and gives her time generously, as Diane attempts to overcome the waves of pain. In supervising the situation while Diane writhes in pain, Alice even allows Gretchen to watch the TV channels Diane doesn’t permit normally. However, this situation warrants it because, as Diane suggests, she can’t deal with her daughter and a migraine at the same time. In Diane’s perspective, Alice’s comfort and care saves her life and the migraine goes away the next day. However, a thread has been woven between the two women that never dissolves, despite their not keeping up the relationship in later years.

Diane helps Alice when she has an argument with Doug that blows up into a full on discussion about divorce. Alice takes Holly and seeks solace from Diane, who readily gives it and comforts her. Diane always thought Doug boring and she encourages Alice to consider other possibilities. Even when Alice resolves to herself emotionally that she and Doug can work out their marriage, Diane offers her place to stay to regroup. This is an offer that later could have become a living arrangement, however, Alice is faithful to Doug and never takes her up on it.

Another theme that comes up when Alice stays the night with Diane is happiness. Diane asks Alice if she is happy, but Alice is more concerned with “keeping up appearances” and trying to make the marriage work after Doug tells Alice he “can’t do this any more.” The idea that people can’t make people happy and rarely does anyone find sustained happiness is something Alice considers as a result of her conversation with Diane that evening. Certainly, it influences Alice in her relationship with Doug, and they eventually divorce in 1978, after Diane moves away.

During the summer and their weekly dinners in the fall, they gradually see each other less and less during 1977 because Alice is engrossed with saving her marriage. However, Diane’s wisdom helps Alice.

At one point Diane lightly suggests they should just travel together and have adventures. Alice’s traditionalism and conventionalism won’t permit it. It is as if Diane intuits Alice and Doug’s marriage will end, but Alice is not ready to admit it. For Holly’s sake she must go through the arduous process of salvage that is fruitless anyway. The possibilities of their close friendship remaining and becoming something more becomes swallowed up in Alice’s conservatism and her fear about leaving Doug. Her inner conflict prevents her from considering other possibilities and freeing herself. Ironically, by the time Alice and Doug divorce and she is free, Diane has left.

Almost a decade later, both women are in New York City. When Alice sees the banner featuring Diane’s works on exhibit, she goes inside the gallery and they meet and discuss how their circumstances have changed. Alice is a middle school English teacher. Diane has become a professional artist who finally finishes her work. When they say their farewells and Alice expresses that she misses Diane and gives her a hug, Diane’s response is “matter-of-fact,” and distant. She reveals to the audience that Gretchen has moved back in with her, has a drug dependency and perhaps made a suicide attempt. She reveals none of this to Alice which is unclear why. When considering if she misses Alice, she reminisces that they were close only for that summer and that is why they drifted apart completely when Diana left and Alice divorced in 1978. Diana even suggests that perhaps it is the memories that she misses.

The final meeting and hand off are fascinating because we note that Diane dismisses Alice, yet gives herself away when she says that Alice is the only one she sends her “art cards” to annually for a decade then stops. Alice loves them and assumes she sends them to everyone, but never replies back. That Diane only sent them to her is momentous. The relationship was important to her for her artistic development. Furthermore, considering Diane and Alice have no partnerships, though Alice admits there were men, but nothing spectacular, we are left wondering that perhaps in a time when the culture wasn’t as oppressive for female-female relationships, they might have had a deep and abiding love. By the play’s end, we understand that their candle of friendship may have nearly blown out, nevertheless they have contributed to each other’s lives and careers beyond measure. Perhaps, it may be rekindled again if one of them takes the step forward.

Summer, 1976 occurs in the undercurrents, the aside comments to the audience, and the subtext. There are the nuanced perspectives and the unspoken spoken. Nothing is manifest. Sullivan’s superb direction and the stellar Linney and Hecht fascinate, in this character study of two women who subtly influence each other to evolve and grow. One day when they are ready, they may possibly reaffirm their connection in the future after their New York meeting. The rest is uncertain as is true to life.

The scenic design (John Lee Beatty) is a minimalist latticed backdrop through which Japhy Weideman’s lighting design flips on the turn of events in their storytelling with beautiful hues. Linda Cho’s costume design is aptly pegged to the characters and Auburn’s characterization. Kudos to Jill BC Du Boff’s sound design, Hana S. Kim’s projection design and Greg Pliska’s original music which elucidates Sullivan’s stylized vision.

Summer, 1976 runs with no intermission, but Linney and Hecht with prodigious authenticity keep the audience rapt and the time becomes transcendent. For tickets and times go to their website https://www.manhattantheatreclub.com/shows/2022-23-season/summer-1976/

‘Prima Facie,’ Jodie Comer’s Tour de Force is a Must-See