Category Archives: cd

‘The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window,’ Lorraine Hansberry’s Mastery of Ideas in a Superb Production

Oscar Isaac’s Sidney Brustein in Lorraine Hansberry’s most ambitious play, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window (directed by Anne Kauffman) never catches a break. Hansberry’s everyman layman’s intellectual is in pursuit of expressing his creative genius and achieving exploits he can be proud of. When we meet him at the top of Hansberry’s masterpiece, which is full of sardonic wisdom, sage philosophy and political realism, Sidney is a flop looking for a reprieve. This revival, first produced on Broadway in 1964, was tightened for this Broadway revival (one noticeable end sequence with Gloria was shaved, not to the play’s betterment). Currently running at the James Earl Jones Theatre with one intermission, the production boasts the same stellar cast in its transfer from its sold out run at BAM’s Harvey Theatre in Brooklyn. The production is in a limited run, ending in July.

It is to the producers’ credit that they risked bringing the play to a Broadway audience, who may not be used to the complications, the numerous thematic threads, the actualized brilliance of unique characterizations and their interrelationships, and Hansberry’s overall indictment of the culture and society. Sign is a companion piece to her award-winning Raisin in the Sun. It explores the root causes why the Younger family is where it is socially and economically. Vitally, it examines the political underpinnings of institutional oppression and discrimination via reform movements, symbolized by the efforts of Brustein and friends who promote the reform candidacy of Wally O’Hara.

To focus her indictment of the perniciousness of political and social oppression, Hansberry examines the vanguard of reformists, Greenwich Village artists, activists and journalists who are emotionally/philosophically ready to make social/economic change of the type that the Younger family in Raisin in the Sun yearns for. However, these Greenwich Village mavericks are the least equipped tactically to sidestep co-optation and the political cynicism of the power-brokers. They realize too late that the money men will fight them to the death to maintain a status quo which inevitably destroys the vulnerable and keeps families like the Youngers and drug addict Willie Johnson struggling to survive.

The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window is timeless in its themes and its characterizations. When we measure it in light of current social trends, it is fitting that the play transcends the history of the 1960s in its prescience and reveals political tropes we experience today. Additionally, it suggests how far society has declined to the point where cultural and political co-optation (a principal theme) have been institutionalized via media that skews the truth unwittingly. The result is that large swaths of our nation remain oblivious to their exploitation and dehumanization, ignorant that they are the pawns of political parties, who promise reform then deliver regression. In short they, like Sidney Brustein and his friends, are seduced to hope in a better world that reform politicians say they will deliver. But when they win, through a plurality of votes from a diverse population, they renege on their promises and continue to do what their “owners” want, which is to “screw” the little people and deprive them of power and a “place at the table.”

Hansberry’s setting of Greenwich Village is specifically selected as one of the hottest, most forward-thinking, “happening” areas in the nation. Brustein’s apartment is the focal point where we meet representative types of those found in sociopolitical/cultural reform movements. His community of friends are activists who believe their friend and candidate Wally O’Hara (Andy Grotelueschen), is positioned to overturn the Village’s entrenched “political machine.” Sidney, reeling from his bankrupted club, which characterized his cultural/intellectual ethos (idealistically named Walden Pond after Henry David Thoreau’s book), purchases a flagging newspaper (The Village Crier) to once again indulge his passion for creative expression. He does this unbeknownst to his wife Iris (Rachel Brosnahan), a budding second-wave feminist who waitresses to support them financially. She chafes at her five-year marriage to Sidney, shaking off his definitions and the identities he places on her, one of which is his “Mountain Girl.”

Activist and theoretical Communist (separated from the genocidal Stalinist despotism) Alton (Julian De Niro), drops in with O’Hara to encourage Sidney to join the crusade to elect O’Hara with the Crier’s endorsement. Sidney declaims their persuasive rhetoric and assures them that he will never get involved in political activism again. However, as events progress, his attitude changes. We note his friends, including artist illustrator Max (Raphael Nash Thompson), stir him to support O’Hara with his excellent articles. Sidney, mocked by Iris about his failures, is swept up in the campaign. When he hangs a large sign in his window that endorses O’Hara, his adherence to push a win for the “champion of the people” increases in fervency.

The sign symbolizes his hope and his seduction into the world of misguided activism, but its meaning changes over the course of the play. Hansberry doesn’t reveal the exact moment that Sidney decides to take up the “losing cause” after he disavowed it. However, his fickle nature and passion to be enmeshed in something “significant” with his friends helps to sway him.

In the first acts of the play, Hansberry introduces us to the players and reveals the depth of her characterizations as each of the characters widens their arc of development by the conclusion. We note the development of Mavis (Miriam Silverman), Iris’ uptown, bourgeois, housewife sister, who is married to a prosperous husband and is raising two sons. We also meet David Ragin (Glenn Fitzgerald), the Brustein’s gay, nihilistic, absurdist playwright friend, who lives in the apartment above theirs and is on the verge of success. Both Mavis and David, like Sidney’s other friends, twit him about Walden Pond’s failure. Mavis and Iris are antithetical in values and Mavis views her sister and brother-in-law as Bohemian specimens to be observed and secretly derided as entertainment. We discover Mavis’ bigotry when she opposes the union of their sister Gloria (Gus Birney), a high class call girl, to Alton, the young light-skinned Black friend.

The genius of this work is in Hansberry’s dialogue and the intricacies of the characterizations. It is as if Hansberry spins them like tops and enjoys the trajectory she creates for them, which ultimately is surprising and sensitively drawn. Organically driven by their own desires, we follow Sidney and Iris’ family machinations, pegged against the backdrop of a political campaign that could redefine each of their lives so that they could better fulfill their dreams and purpose. However, the campaign never rises to the sanctity of what a true democratic, civic, body politic should be. Indeed, the political system has been usurped in a surreptitious coup that the canny voter “pawns” are clueless about.

Tragically, instead of political power being used to combat the destructive forces Hansberry outlines, some of which are discrimination, drugs, law-enforcement corruption, economic inequity and other issues that impact the Brustein’s and their friends’ lives, O’Hara and his handlers have other plans. But first, they cleverly convince the voters a win is unlikely and they pump them up to believe in the possibility of an O’Hara success that would be earth-shattering and revolutionary. This, we discover later, is a canard. The “revolutionary coup” can never occur because the political hacks control everything, including Sidney’s paper which they exploit to foment support for O’Hara. How Hansberry gradually reveals this process and ties it in with the relationships-between Iris and Sidney, Alton and Gloria, Iris and Mavis and the other friends-is a fabric woven moment by moment through incredible dialogue that pops with quips, peasant philosophy, seasoned wisdom, and brilliant moments that evanesce all too quickly.

By the conclusion, the solidity of the characters’ hopes we’ve seen in the beginning have been dashed to fold in on themselves. Both Iris and Sidney learn to reevaluate their relationship with each other and their misapplication of self-actualization, which allowed a tragedy to happen. Likewise, Alton’s inflexibility about his own approach to his place in an exclusionary, oppressive culture ends up contributing to a tragedy that might have been prevented. In one way or another, these characters particularly, along with David’s self-absorbed nihilism, contribute to Gloria’s death.

Symbolically, Hansberry points out that love and concern for other human beings is paramount. Too often, relatives, friends and cultural influences contribute to daily tragedies because human nature’s weaknesses in “missing the signs” contort such love and service to others. Ironically, politics, whose idealized mission should be to reform and make the culture more humane, decent and caring, is often hijacked by the powerful for their own agendas to produce money and more power and control. The resulting misery and every day tragedies accumulate until there is recognition, and the fight begins to overcome the malevolent, retrograde forces that O’Hara and his cronies represent.

This, Sidney vows to do with his paper and Iris’ help in a powerful speech to O’Hara proclaiming a key theme. To be alive and not spiritually, soulfully dead, one must be against the O’Haras of the world and the forces of corruption. To support them is to support death and dead things. To recognize how the power-brokers peddle death, one must discern their lies and avoid being lured into their desperate cycle of destruction, which they control to keep the populace oppressed, hopeless and suicidal.

The actors’ ensemble work is superior. Both Isaac and Brosnahan set each other off with authenticity. Miriam Silverman as Mavis hits all the ironies of the self-deprecating housewife, who has suppressed her own tragedies to carry on. And Julian De Niro’s speech about why he cannot love or marry Gloria is a powerhouse of cold, calculating, but wounded rationality. Hansberry has crafted complex, nuanced human beings and the actors have filled their shoes to effect their emotional core in a moving, insightful production that startles and awakens.

The play must be seen for its actors, direction, and the coherent artistic team, which perfectly effects the director’s vision for this production. These artists include dots (scenic design), Brenda Abbandandolo (costume design), John Torres (lighting design), Bray Poor (sound design), and Leah Loukas (hair & wig design).

This must-see production runs under three hours. For tickets and times go to their website https://thesignonbroadway.com/

‘Prima Facie,’ Jodie Comer’s Tour de Force is a Must-See

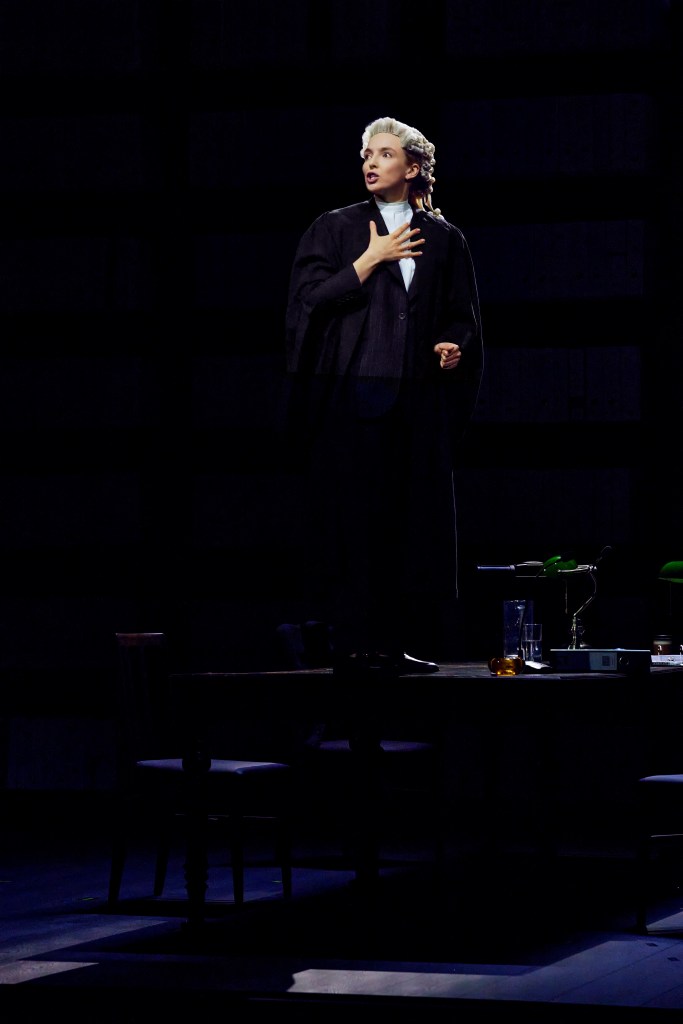

One receives a stunning, thematic walk-away from Suzie Miller’s Prima Facie, directed by Justin Martin, currently at the Golden Theatre for a limited engagement. Prima Facie (the Latin legal term means on the face of it), stars the inimitable Jodie Comer in a well-heeled, solo performance. She won the U.K.’s Olivier Award for her portrayal of the assertive, successful, high-powered barrister, Tessa Ensler, who adores the rules of the law with an almost religious fervor. How Comer, the director and Miller effect Tessa’s roller-coaster ride toward hell, engaging the audience so you can hear a pin drop, reveals their prodigious talents. In Prima Facie, they’ve created a thematically complex production of theatricality and moment.

Though there are gaps in the play, Cormer’s performance bestrides them and raises numbing, thematic, rhetorical questions. Initially, the answers escape us, as we become involved in Tessa’s journey toward personal revelation. The strength of the play is in the slow arc of character development, which Cormer senses in her bones and conveys with power and flexibility, as she draws us in to Tessa’s plight. Her vocal and emotional breadth are superb and wide-ranging. Comer’s near-flawless expose, starkly pinpoints Tessa’s confession and admission of repeated self-betrayal and unwise decision-making. How Tessa is prompted to self-destruction by the patriarchal culture’s influence, confounds us. However, the audience cycles through the nullifying events she experiences and gradually becomes enlightened to her devastation.

From the top of the play, through to Miller’s characterization and Cormer’s sometimes breezy, dualistic, self-satisfied and impassioned recounting of her success as a defense barrister, we note she plays to win against the tricks of the police and the tactics of the prosecution. Her metaphoric descriptions are humorous. She is a winner at the law, always up for social justice, jumping into challenging cases against the prosecution. We learn many of the cases are for sexual assault, which she defends her clients against to “get the criminals off,” as her mother suggests. Blindly, with her own rational justifications, Tessa has greedily internalized the patriarchy’s folkways and legal mores. She believes herself immune as a barrister in a justice system, which she thrillingly and ferociously advocates. It is a game to her. She humorously pegs herself as a thoroughbred in a race, during which she expertly uses her strategies to anger, lure and upend the prosecution’s witnesses, who can’t “see her coming.”

Believing herself to be in control, she succeeds in becoming a star defense barrister, who wins her cases for her male clients. That she is a dupe, and a puppet female that the legal system has cultivated to perpetuate its entrenched hierarchy and male-informed justice, she only awakens to when she herself falls prey to assault. Too late, she becomes like the female victims she shreds, victimizes and makes look guilty on the witness stand to benefit her male clients. As Cormer and Miller subtly reveal, Tessa has been riven asunder by her desires to best the upper class barristers she competes against. To do this, she must take on their most obnoxious of attributes and suppress her true identity as the attractive, vulnerable, learned, emotional woman, who desires love and a relationship with a guy.

Thus, like most women in the patriarchal culture, she must negotiate two selves and protect both from each other. Importantly, she must not allow the predominance of one over the other in a blood sacrifice to “rise to the top,” or be the handmaiden of a partner, supporting him financially, if he is a slacker. Worse, she must not couple up with another barrister as ferocious as herself in a competitive, combative relationship. Nor must she throw down her career to wrap herself in the “lesser roles” of housewife, mother, wife, while her partner enjoys the power and amenities (sexual peccadilloes) his career may offer. However, as Cormer and Miller portray Tessa, the “feminine” side is not tended to, so it erupts when a guy lures her away from her career identity.

Interestingly, to convey the mystery of this inner conflict, which Tessa ignores, Miller sanitizes Tessa’s descriptions and removes gender references, when discussing her cases as “the barrister.” She doesn’t use names. Instead, she employs legal terms. Objectification and impersonalization are paramount. Cormier’s Tessa internalizes the abusive male folkways and embraces them because she is in a position of power. She doesn’t realize that she is a dehumanized robot, exploited by the patriarchy precisely because she is a woman defending men (a supreme irony). Just like the guys she competes with, she is all about the legal game and winning the race. We understand that the police predominately are males, and she bests them and her male barrister colleagues. One she excels against is Julian, who ruefully comments on her repeated success.

Occasionally, a clue is given. Her upper class friend, who started law school with her, drops out and becomes an actress. Tessa is the one in three, who makes it because of her persistence, brilliance and aggressiveness against all comers. Indeed, the very attributes that are rewarded in the legal profession are more masculine than feminine. That she has chosen to defend males against females in a crass exploitation of her skills is pointed out by a female colleague, who questions her.

Though her colleague intends to bring Tessa to enlightenment, Tessa describes how she conveniently ignores the question which hits us over the head with its answer. Apparently, Tessa doesn’t mind that her position is being undermined by defending men in cases against women. Nose to the grindstone, she aggressively succeeds, and all should get out of her way. The undaunted barrister personality proves she is the best and “fits right in.” However, there is the suppressed side of her personality, where she can’t compete with “all comers,” and she will never fit in. She can’t compete with males in their gender antics. She can’t behave like men sexually because the standards are different for men and women. Such traditions and double standards die hard.

There’s the rub. Women are still oppressed by the ancient folkways that manifest in sub rosa male and female attitudes. These egregiously include the notions that men are not “whores,” they’re just good ole boys, having fun. After all, boys will be boys. On the other hand, women are referred to as “sluttish” according to double standards. Thus, a woman’s response to sexual assault can be easily confounded by the legal questioning in a system that “doesn’t get how females respond and freeze,” when they are sexually assaulted. The legal interrogation system that allows for only one word answers is oriented toward the masculine. If there is fuzzy thinking and confusion on the stand, it means intentional obfuscation and guilt. The legal system’s foundation is historically entrenched in preeminent male beliefs, behaviors and attitudes, integral to its structure of obtaining justice for the accused. This is especially so when the charge is a gender crime against women.

The event that turns Tessa’s world upside down and opens her understanding is her non-consensual rape by a colleague with whom she previously was intimate. The legal parameters of justice indicate that non-consensual sex is the red line beyond which no partner can go, because it involves force and pushing oneself on the autonomy of another. Tessa ends up in a situation with barrister Julian making one bad decision after another that she knows will make her appear guilty. In effect, she is making herself the victim, but can’t stop herself. In applying the law to her own behavior, she realizes her mistakes, however, she decides to press charges against Julian. Despite knowing she should wait for a female officer, who will understand from a female perspective, she relates what happened to a male officer in charge. She knows what to do, but does the opposite, time again during this experience with Julian to seek justice.

We follow Tessa’s story from one sequence of events after another, during Tessa’s two year waiting period to eventually get into the courtroom and testify on her own behalf. As she faces Julian and the defense barrister colleague realizing what’s coming, she is shocked. The entire courtroom of officials is filled with men. She is the only woman. And it is there that the tactics she strategically, confidently, aggressively used against females to defend her male clients, now are employed against her. She becomes her own victim. By her own barrister standards, she realizes she is guilty. However, she is not on trial, Julian is.

In her final self-betrayal, the internalized patriarchy of justice must release Julian as an innocent. There is one guilty person, the woman, who somehow is lying and magically fabricating that a non-consensual rape occurred. Because of her fuzzy and at times confused, frozen responses, she raises doubt that a rape occurred. Thus, victimizing herself, she turns the barrister Tessa against her female identity, and is guilty. The prosecution loses the case to Julian, who she victimized with her accusation.

In an interesting turn, Tessa is able to express her feelings. She addresses the court absent the jury and finds her voice. Cormer rises to the occasion during the courtroom scenes she effects. She is especially powerful in her indictment of a patriarchal legal system established for the betterment of males, particularly those who have money and are in the upper class.

In her concluding salvo to the audience, tears streaming down her face, Comer’s Tessa adjures wistfully that “something must change.” Though we agree, after her revelations, the self-absorbed, anti-climactic assertion rings hollow. Indeed! She must change. She must stop internalizing “the perfection” of male folkways, which historically have destroyed women. She must resign from her position of defending men in sexual assault cases. She must negotiate the balance in her personality. She must not allow “the barrister” to predominate and harm the feminine Tessa, mistakenly applying male double standards to her personal life. She must not forget her gender places upon her an unforgiving female ideal of perfection and purity, she must adhere to. Ironically, there is no move to understand that she must transform herself to bring about the change that she seeks. This irony needed to be emphasized in the staging, which at times is lacking in pointing up the dualism in her character.

However, Cormer’s plaintive cry reveals her regret, which is a self-betrayal and utter confusion at finding herself where she is in her life. She has backed herself into a corner. If she leaves the profession after losing the case, the patriarchy will have won. If she stays and continues to defend men, as she has done before to “put the terrible events behind her,” the patriarchy will have won. If she moves to the prosecution side, she will no longer be “the star” at the top of the ladder. She is left broken and crying at her self-entrapment in the stunning irony as the stage lights dim. The effect is numbing. What did we just see? Her generalized cry for change lacks impact and force. However, her tearful regrets are the first step in a long process of self-correction, which may lead to social reform.

Miller’s thematic “call to arms” is clear. Every woman in the audience must change internally. They must uproot every internalized desire of the patriarchy which defines them and denies them. They must define themselves. They must not believe the lie they can compete with men as Tessa attempted to compete and allowed herself to be duped and exploited. Sadly, in the attempt to compete women internalize folkways that necessitate their own co-optation that leads to self-harm.

Miller’s point about the judicial system concerning rape and sexual abuse is thought-provoking. Only with protests might the legal system be reformed to accommodate the female perspective about rape to use a different form of questioning that drives to the truth. But the underlying folkways that have been seething for millennia and are global in scope must be dealt with. If not, men will continue to conquer, divide and co-opt to undermine women. They are incredibly practiced at it. This is especially so with regard to institutional misogyny that is subverted/invisible because it is inherent in the structures men have created to maintain privilege and power.

Kudos to Miriam Buether (set & costume designer), Natasha Chivers (lighting designer), Ben & Max Ringham (sound designers), Rebecca Lucy Taylor (composer), Willie Williams (video). Prima Facie is not to be underestimated and labeled as a “feminist” treatise that is against men, so those who wish to ignore what Miller’s themes are conveying can easily dismiss them. The production is complex in a time when #metoo often has been misunderstood, politically abused and misapplied. The insert with the program is a reminder of the catastrophic consequences of rape as a crime of gender annihilation. One statistic stands out. Approximately 70 women commit suicide every day in the US, following an act of sexual violence.

The point is not that sexual violence is sexual. It is that gender/sex is used to annihilate psychically, and render the “other” silent. Prima Facie investigates this on a more profound level than one expects. For that reason, it is a must see. And Jodie Comer is just terrific. For tickets and times to this play with no intermission, go to their website https://primafacieplay.com/

‘Crumbs From the Table of Joy’ Keen Company’s Revival of Lynn Nottage is a Must-See

From the excellent selection of music that fills the auditorium before Crumbs From the Table of Joy begins, to Ernestine Crump’s (Shanel Bailey) summation of the future after the roiling events with her family subsides, the Keen Company’s fine revival of Nottage’s play endears us. The playwright’s simplicity focuses on the hardships and relationship dynamics of a single father and two teenage daughters, migrating from the Jim Crow South to a Brooklyn recovering from the vagaries of WW II. Directed by Colette Robert, the heartfelt, lyrical production runs with one intermission at Theatre Row until April 1. It is a must-see for its superb performances and incisive, sensitive and coherent direction.

Ernestine is our guide through the year-long experiences negotiating her mom’s death and the family trials without their beloved mother to seamlessly make their lives easier. Their mom is intensely missed by all, especially Godfrey Crump (Jason Bowen) who yearns for companionship and tries to suppress his grief by joining up with Father Divine’s Peace Mission fellowship. Ernestine’s poetic recollections of the grieving time and the year of transformation, reveal a witty, talented raconteur. Wise beyond her years, she makes the audience her confidante to reveal the frightening, unfamiliar city and “romantic Parisian apartment” which sister Ermina (Malika Samuel) calls ugly. Occasionally, she calls up in her imagination scenes as she’d like her life to be, which the actors show with humorous results. Then the unfortunate reality encroaches, and what she wishes dissolves to what is.

The family are fishes out of water in an alien environment that never seems welcoming. The Brooklyn schools put Ermina in a lower grade. The students ridicule their country braids and home made dresses sewn with love. Generally they are treated with disdain and indifference. Surrounded by Jewish neighbors who remain aloof in their whiteness, they dp become friendly with upstairs neighbors who ask them to be their Shabbos goys.

They envy the elderly Levys, who seem joyful and full of laughter as they listen to radio and watch their TV programs. On the other hand Godfrey denies Ernestine and Ermina any entertainments on Sundays. Godfrey is an adherent of Father Divine’s principles which require sobriety and living abstemiously with few pleasures except Father Divine’s holy word. Thus, Ernestine’s misery is acute. but she overcomes her upset through humor and irony. Nottage bonds us to her heroine because of her alertly sage descriptions and authenticity, which never devolves into self pity. To support her dad and sister whom she loves, she keeps her own counsel and studies hard to finish high school. A senior she becomes engrossed with making her graduation dress by hand, working her seamstress skills. Hers will be the celebration of the first family member to receive a diploma.

While Ernestine applies herself in school, Ermina, who is 15-years old, fights her way into the social set and eventually becomes interested in boys. To establish that she won’t take sass from anyone, Ermina has her first successful fight and brings home the spoils of war in her pockets: a handful of greasy relaxed hair and a piece of grey cashmere sweater.

For his part their dad weeps, works nights at his job at the bakery, and loyally follows Father Divine. He counts on the minister to help him heal from the agonizing loss of his wife. Ernestine tells us that Father Divine has so enamored Godfrey that to be closer to him, he moved them to New York where he mistakenly thinks Father Divine lives because of a return address on the newsletter he receives as a subscriber. Their dad believes Divine’s “wisdom” is from God and he adheres to Divine’s principles to live cleanly, without alcohol or dancing or drugs, and be as devoted as a monk with celibacy as a badge of honor. Ernestine quips that this behavior is embraced by Godfrey, who never went to church or tipped his hat to a lady before they moved to Brooklyn. As for the other behaviors she doesn’t mention, we assume he did them all before their mother died.

Their home life revolves around Father Divine as their father attempts to become more spiritual and understand as much as possible under Divine’s tutelage which he seeks as he writes letters to him asking God’s advice to traverse this rough time in a bigoted environment of white people. That it was worse in the South doesn’t quite register and Nottage doesn’t make it a point. What she does indicate is that Godfrey doesn’t note the differences. For her part Ernestine appreciates that she is able to sit between two white girls touching shoulders in a movie theater, where this is not possible in a Jim Crow South which we infer from her excitement and enthusiasm. Also, she and Ermina like their nice neighbors upstairs who give them quarters for turning on the lights and the TV which they sometimes get to watch. However, to Godfrey, “white people” are a universal stereotype to be avoided and mumbled about.

Ironically, Ernestine points out his hypocrisy about selective criticism. He accepts Father Divine’s choice of a white wife to be another perfection of Godliness. Ernestine, who distrusts Father Divine, points out the difference between the God-like, elite Divine’s privilege to have a white wife, yet criticize white people to his Black followers. Meanwhile, her dad is just a poor Black man who sucks up a few crumbs from under the table of his life, which appears a drudgery especially with no woman at his side.

Enter Lily Ann Green (Sharina Martin) their mom’s deceased sister, who blows in unannounced, with values contrary to Father Divine/Godfrey and behaviors which upset Godfrey and put him on edge. Ernestine is thrilled she is there, even though Lily crashes with them, is completely self-absorbed and pushes her communistic beliefs wherever she goes,which is why she can’t hold a job. Interestingly, Nottage floats the two disparate philosophies which were to bring salvation to the Black society in America in the 1950s as sold and marketed by both: religion and the communist party.

Both preachers and communist leaders embraced the African American cause and, at their most egregious, exploited it for their own use. When Ernestine uses communist ideas in an essay that she hears Lily spout (this was during Senator Joe McCarthy’s Red Scare) her teacher is in an uproar. Likewise, Lily Ann ends up compromising Godfrey’s situation at work. Ernestine is forced to apologize as is Godfrey, who argues with Lily about not pushing communism vociferously to his daughters and others. He believes she is only making trouble. Though Lily Ann is interested in Godfrey and makes a play for him, he rejects her because he doesn’t agree with her politics and she dislikes Father Divine.

When the circumstances between them explode, Godfrey takes off a few from the family in frustration. During this respite, he meets Gerte Schulte (Natalia Payne) who emigrated from Germany after the war. Like Godfrey she is desperate for companionship and looking for someone to take care of her. Godfrey opens his heart and shares his circumstances. When he discusses Father Divine, she is receptive and together they seem to meld because of Gerte’s flexibility and charm. She is the antithesis of Lily Ann’s loose lifestyle, political determinism and stubbornness in having the upper hand with men.

Where Lily Ann is a catalyst and mentor for Ernestine and Ermina, Gerte becomes the catalyst to change their lives and split them apart. Nottage leaps her play’s action quickly forward when Godfrey brings Gerte home to introduce her to his daughters and Lily Ann. With her seductive, sweet charms, Gerte ingratiates herself into Godfrey’s life, moving herself from girlfriend to wife in a matter of a few days. The siblings are shocked as is Lily Ann. Godfrey expects all of them to live together and accept Gerte as his new wife. The results are not only humorous, they are necessary for Ernestine’s and Godfrey’s growth, as well as Lily Ann’s movement away from the dream of settling down with her sister’s husband.

As Ernestine Crump, Shanel Bailey is a phenomenon. Her narration is on-point, sensitive, nuanced and heartbreaking, especially at the end when she discusses what happens to each of the family members. Mindful of the narrative’s lovely poetic phrases, Bailey travels forward in character portraying Ernestine’s feelings in active dialogue with her dad, Lily Ann and Gerte, then seamlessly transfers to narrating her ironic perspective of them with grace. Bailey is winning and the production which hinges on her broad acting talents is strengthened with her brilliance of authenticity.

Though all of the ensemble shines, held together through Robert’s fine direction, another standout is Natalia Payne’s Gerte. Her accent is near perfect as a a German swanning through English. Payne makes Gerte likeable in her color blindness and utter humanity, as she forges a path for herself after the war. Though Nottage doesn’t fill in much of her backstory, we see she is a charming operator with resilience and an ability to read and understand situations, a survivalist. She and Godfrey end up with each other as a mutual benefit and by the end of the play, they move toward the intimacy and companionship they seek and need.

Malika Samuel’s Ermina is a breath of joyful fresh air. Her role is an addendum. It is a shame that she doesn’t have more dialogue for her funny, bright personality is winsome and the relationship Samuel and Bailey effect together rings with authenticity.

Nottage’s mouthpiece for her ideas, Lily Ann, is the most difficult of the characters to like because underneath her rhetoric, she is the most evasive. Though we attempt to infer the subtext of her character, Nottage doesn’t give us much to go on past what she stands for and says she believes in. However, her actions speak louder than her words and when Ernestine attempts to find the Harlem location of the communist party, the address that Lily Ann gives her doesn’t ring true. As Lily Ann, Sharina Martin is tough, manipulative, seductive and open-hearted with the sisters. She also layers Lily Ann’s personality so that we are wary that she is fronting and not delivering the truth to the family as she should be.

Jason Bowen’s Godfrey is spot-on believable and inhabits the role of the father desperate for answers in a world whose corrupt values make no sense except to be an incalculable frustration. His faith in Father Divine is believable to the point where we want Divine to be real. If he is duping Godfrey, who is vulnerable and heartbroken, it is a bitter and enraging Black on Black exploitation, skirting criminality. Because we empathize with Bowen’s Godfrey, we want the best for him. As Ernestine does we question his weak desperation falling for Gerte and marrying her so quickly. However, both are so needy. In the last scene Ernestine notes that Godfrey’s celibacy ends when Gerte and he make up after fighting. Bowen and Natalia Payne convey a roller coaster of emotions in their last scene together.

Kudos to the Keen Company’s creative team who bring together Colette Robert’s vision of the other 1950s America and how to prosper in spite of it. Creatives include Brendan Gonzales Boston’s spare, functional period scenic design, Johanna Pan’s costume design, Anshuman Bhatia’s lighting design, Broken Chord’s sound design and Nikiya Mathis’ wig design.

Crumbs from the Table of Joy continues until April 1 at Theatre Row. For tickets go to their website: https://www.keencompany.org/crumbsfromthetableofjoy

League of Professional Theatre Women Press Release

League of Professional Theatre Women

December 8, 2022

For immediate Release

Contact: Meg Gilbert

Press@TheatreWomen.org

Tel: (646) 386-6579

THE LEAGUE OF PROFESSIONAL THEATRE WOMEN LAUNCHES

COMPREHENSIVE PAY EQUITY RESEARCH STUDY

AS A PART OF THIER 40TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION

As part of its mission to advocate for parity in employment, compensation and recognition for women theatre practitioners through industry-wide initiatives and public policy, the League of Professional Theatre Women (LPTW) announces the launch of an industry-wide, comprehensive pay equity research study. Focusing on New York City and New York State theatre professionals in a variety of disciplines, the study will include qualitative and qualitative data collected through anonymous surveys and interviews in order to assess economic equity and hiring practices during the 2018 – 2022 seasons.

The Study is developed in partnership with the research firm Network for Culture & Arts Policy (NCAP) to examine pay equity, opportunities, negotiation practices, and the financial needs of theatre professionals across New York. It will be distributed to theatre professionals through unions, membership organizations, theatre staff, and guilds. All theatre professionals are encouraged to participate. All responses will be collected anonymously.

The study will remain open through December 23, 2022. All theatre professionals working or living in New York State can access the survey here: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/LPTWEquity

Results will be analyzed and shared via industry convenings, town hall gatherings, and a full report of findings in fall 2023. The data will help to determine the LPTW’s priorities for targeted programming to support pay equity among industry professionals and to facilitate dialogue among industry leaders.

“We are proud and excited that LPTW is conducting this important research project as part of our 40th Anniversary celebration,” said LPTW co-presidents Katrin Hilbe and Ludovica Villar-Hauser. “Despite recent legislation concerning hiring practices – equal pay for equal work, transparency in salary ranges for job postings – there is still an enormous amount of secrecy surrounding money. This study is an important step towards true gender equity with regard to salaries and pay.”

The LPTW Pay Equity Research Study is supported in part by a grant from NYSCA Regional Economic Development Councils.

The League of Professional Theatre Women, (LPTW), now celebrating its 40th Anniversary, is a membership organization championing women in theatre and advocating for increased equity and access for all theatre women. Our programs and initiatives create community, cultivate leadership, and increase opportunities and recognition for women working in theatre. The organization provides support, networking and collaboration mechanisms for members, and offers professional development and educational opportunities for all theatre women and the general public. The LPTW celebrates the historic contributions and contemporary achievements of women in theatre, both nationally and around the globe, and advocates for parity in employment, compensation and recognition for women theatre practitioners through industry-wide initiatives and public policy proposals.

The Network for Culture and Arts policy (NCAP) is a full-service research and consulting firm committed to advancing organizations and individuals that support cultural and social initiatives, programs and enterprises from idea formation to realized implementation. Through mixed methods research, paired with expert strategic planning and implementation services, NCAP examines cultural and social activities, trends, policies, and practices that aid in shaping our lived experiences. We work with a range of cross-sector partners to substantively investigate how cultural activity and socially responsible investments offer economic and developmental benefits to enrich our communities in concrete ways that advance equity, access and prosperity.

The Regional Economic Development Councils (REDCs) support the state’s innovative approach to economic development, which empowers regional stakeholders to establish pathways to prosperity, mapped out in regional strategic plans. Through the REDCs, community, business, academic leaders, and members of the public in each region of the state put to work their unique knowledge and understanding of local priorities and assets to help direct state investment in support of job creation and economic growth.

‘KURT VONNEGUT: UNSTUCK IN TIME,’ a Brilliant, Heartfelt Documentary by the Director of ‘Curb Your Enthusiasm’

Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007) is perhaps one of the most insightful novelists and humorists of the twentieth-twenty-first century. Robert B. Weide, whose funny bone and fascination with great comedians (he won awards for his work on his documentaries about Lennie Bruce and W.C. Fields) found him helping Larry David launch Curb Your Enthusiasm which he then directed the first five years of the show, winning awards.

That Weide adored Vonnegut as a teenager and was influenced in his career by Vonnegut’s sardonic humor and philosophical, dire wisdom that translated into crazy characters and sci-fi-like plots, seems a no brainer; for at heart, Vonnegut, like all comedians creates humor and irony from soul hell and torment. Where Weide stands out from the rest of the Vonnegut acolytes is that early on in his struggling career, he contacted Vonnegut expressing interest in making a documentary about his hero. When Vonnegut accepted, Weide began the long journey (almost 40 years) to get the film made.

However, like much of what we experience in life, it is the journey that is paramount, and for both Vonnegut and Weide, the journey of working together, connecting and becoming friends seemed to be the most vital enjoyment of their collaboration. That eventually, Weide was able to sift through the mounds of Vonnegut pictures, family films, Weide interviews with family, and Vonnegut on trains and in cars and taking stock of the video clips of his speaking tours to cobble together a noteworthy and maverick film about Vonnegut’s life, will be treasured by fans and newbees alike.

Most importantly, the film introduces an entirely new generation of ironists and satirists to Vonnegut’s soulful miseries turned into sardonic social commentary. Vonnegut always found the human comedy of politics, cultural idiocies and their attendant propaganda pushers cannon fodder for his word bazookas. Weide, who wrote and produced the film and co-directed it with Don Argott, with his editing team, selected the most salient Vonnegut quotes from his works and interspersed them with clips of his videoed tours to pepper a chronicle of Vonnegut’s life in a back and forth circular narration. When useful, Weide has Sam Waterson read some of the quotes from the novels, etc. The rendering is enthralling and what emerges is the everyman that even the most jaded of nihilists will find themselves agreeing with, despite themselves.

What makes the film extraordinary is that in becoming so familiar with his subject, Weide’s conveyance to present him is as a documentary in a documentary. In structure, it becomes downright Vonnegutesque. Vonnegut continually interrupted the flow of action in some of his novels by interjecting the writer’s voice, indeed, perhaps his alter ego in an absurd fashion as we see in drawings in Breakfast of Champions.

Likewise, Weide interrupts his Vonnegut chronicle to interject his thoughts about Vonnegut and his own life in making the documentary. Weide parallels the time period of his life with his ongoing interviews and communications with Vonnegut, critics and his children. He acts almost as an apologist would in averring and showing why it took him so long to make the film. What I find so memorable is that we see both men aging into success and/or the next stages of their lives. It is ironic that now, after his death, Vonnegut is turning over a new chapter in having his legacy brought forth once more; interestingly, though not a lot of fans followed him here, though he never left off writing. With his revitalized legacy in Weide’s film, he will be rediscovered, discovered, read and reread, and appreciated or damned for his great levity and sage quips and droll, nightmare plot scenarios…and his essays and short stories.

As a writer I found the documentary in a documentary structure intriguing and rather tongue-in cheek. It twits the documentary genre because Weide makes it very clear that he is completely enamored of this great social satirist and writer and thrilled that he was his friend. That intimacy and revelation was Weide’s choice and at one point, he also makes it clear that with all that he has put into this film, there is much more that was left out, i.e. the personal moments that happened between the two friends.

Rather than to point out all of the aspects of the Vonnegut chronicle, which Weide seems to leave no stone unturned in Vonnegut’s life, he shows the arc of Vonnegut’s career influences and development. Weide jumps around which makes the documentary intriguing, as he makes connections with his own insights and life, then jumps back and forth, past to present to past to current time. Superb. None of this is in chronological order per se; it is in thematic order. For example we discover late into the film that Vonnegut’s mom committed suicide. WHAT! We get to draw the conclusions as Vonnegut discusses how they found her.

We discover how and where Vonnegut grew up, his joining the service and fighting in WWII to experience the seminal aftermath of the bombing of Dresden, Germany which haunted him for all of his life even after he attempted to expurgate it in his first novel of great success, Slaughterhouse Five. The novel, was a war story about a man who’d become “unstuck in time,” with an ability to leap through life, out of time rather like the mystical experience Vonnegut explains he had in Germany when he envisioned the disaster of Dresden before it happened.

Weide leads us to discover how he developed his humor and social insights about technology; his brother with whom he was close was a world class scientist, forward thinking and forward moving. At times Vonnegut lived hand to mouth after he worked in the GE empire in Schenectady and left it because writing copy was nullifying. But his first wife encouraged him to write fiction; he supported himself writing short stories in the hey day of short story writers, for magazines like Colliers, until TV came and the market dried up. A key turning point in his life and career was the death of his sister and his brother-in-law. He accepted responsibility for taking in their four sons and raising them in a house of chaos. The interviews with Vonnegut’s children are priceless.

Vonnegut’s struggles were the nerve-wracking journey that ended in bankruptcy and forced the family to move and Vonnegut to teach to make some money until he struck gold with Slaughterhouse Five, became a celebrity, hobnobbed with famous writers and divorced his wife, though he stayed close to his three children. In the republication of the novels he wrote before Slaughterhouse Five, he earned enough money to be comfortable, if not happy; indeed, he became more ironic and annoyed and wrote about it with less success and popularity which he never returned to after the 1970s. It was around this time that Weide found him and the interviews with Vonnegut, his children and noted writers and friends and Vonnegut’s novel writing and speaking engagements continued, though his popularity waned. Interestingly, they collaborated on a film based on Vonnegut’s Mother Night, which was hugely unsuccessful.

Though some critics of the film find it distracting that Weide interjects himself in the film with their relationship, I found the clips profound. Weide is revealing the decades long influence Vonnegut had upon his life and career. Perhaps, it is one of the reasons that Weide even made the film at all; to get down as much as he could that fans would appreciate, for they understand Vonnegut’s profound influence. Yet, in what Weide left out, only he will be reminded of the most vital and personal portions he alone experienced, that he keeps as a treasure to himself. For those who don’t like Vonnegut, it’s a ho hum. For fans, their relationship humanizes Vonnegut who had clay feet after his divorce and falling off the Best Seller lists into a kind of writer celebrity oblivion.

However, as one does acknowledge with close friends, all of it, even what might be the little insignificances are important. And enough of the personal intimacies come through between Weide and Vonnegut and his family (smoking a Pall Mall cigarette with his daughter en memoriam) that I found myself broken-hearted that I got to experience Vonnegut in a new way, and that he left this planet and I was too caught up in my own life to stop a moment and reflect about his books and why they so moved me at the time. Though I was a great Vonnegut fan in college, I stopped reading him, put off by his son’s “revelations” about himself and his father.

For me and for others, Weide’s film opens up a new door to appreciate Vonnegut the social critic and voice of thunder railing against the worst of human ills. And we get to appreciate the how and why he was who he was, an American man who carved a place for himself in the minds of individuals to influence their thinking philosophically. For that alone this film is vitally current. Vonnegut fits with our time even more so than the time that found him resonant.

KURT VONNEGUT: UNSTUCK IN TIME is available in theaters and on VOD

VIEW TRAILER HERE.

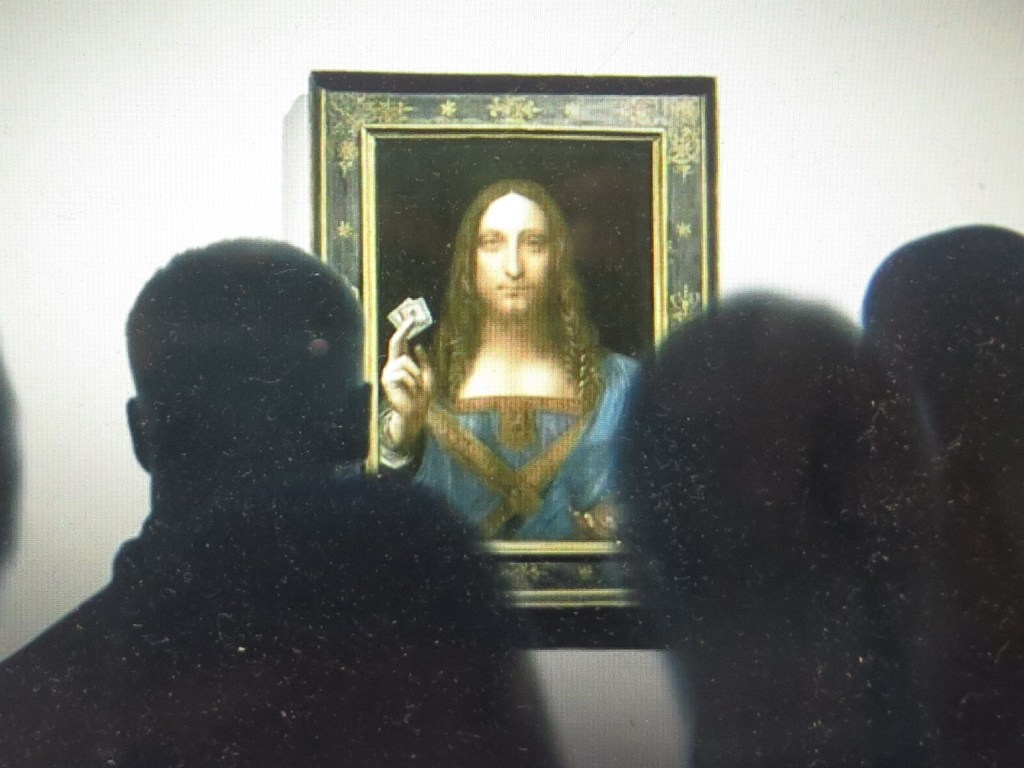

‘The Lost Leonardo’ World Premiere at Tribeca Film Festival 2021

The Lost Leonardo directed by Andreas Koefoed and written by Duska Zagorac, Mark Monroe, Andreas Dalsgaard, Christian Kirk Muff and Andreas Koefoed. The film is a fascinating documentary that delves into the nail biting discovery of the painting Salvator Mundi (a portrait of Jesus) that was ill-used, in ragged condition and an obscurity for decades or centuries depending upon what you believe. It was sold for a mere $1,175 in 2005 by New Orleans auctioneers who didn’t really pay much attention to provenance or the possibility of its potential greatness. However, purchasers who hunt for sleepers (undiscovered renowned works) thought it might have value. They wanted it to be restored with the intention of reselling it. How lovely if it slipped under the radar of the New Orleans merchants who were not schooled in high Renaissance art. Finders keepers and all that!

Thus begins the journey of a painting that remains a mystery to this day and has been examined, pawed over and quibbled about by some of the most prestigious art galleries, museums and their curators in the world. Like a well-heeled detective, Andreas Koefoed cobbles together the video clips of individuals who pondered over, investigated and worked on the Salvator Mundi. He also interviews art critics, museum curators, experts, scholars, art historians, investigative journalists, the Founder of the FBI Art Crime Team and shady art dealer businessmen who profit off of billionaires who purchase such costly works privately or at auction. These wealthy could care less if the provenance is in question as long as the perception remains that it is authentic. They do this in order to bury their money in the painting purchase which hides a record of their wealth from the pernicious eyes of tax collectors.

The adventure Koefoed embarks on is thrilling, and he unspools the clues like a master mystery writer. The chase of whether this work is truly the “lost Leonardo” keeps one enthralled. However, there is no conclusive finality and uncertainty reigns with every word his subjects use to speak about the painting.

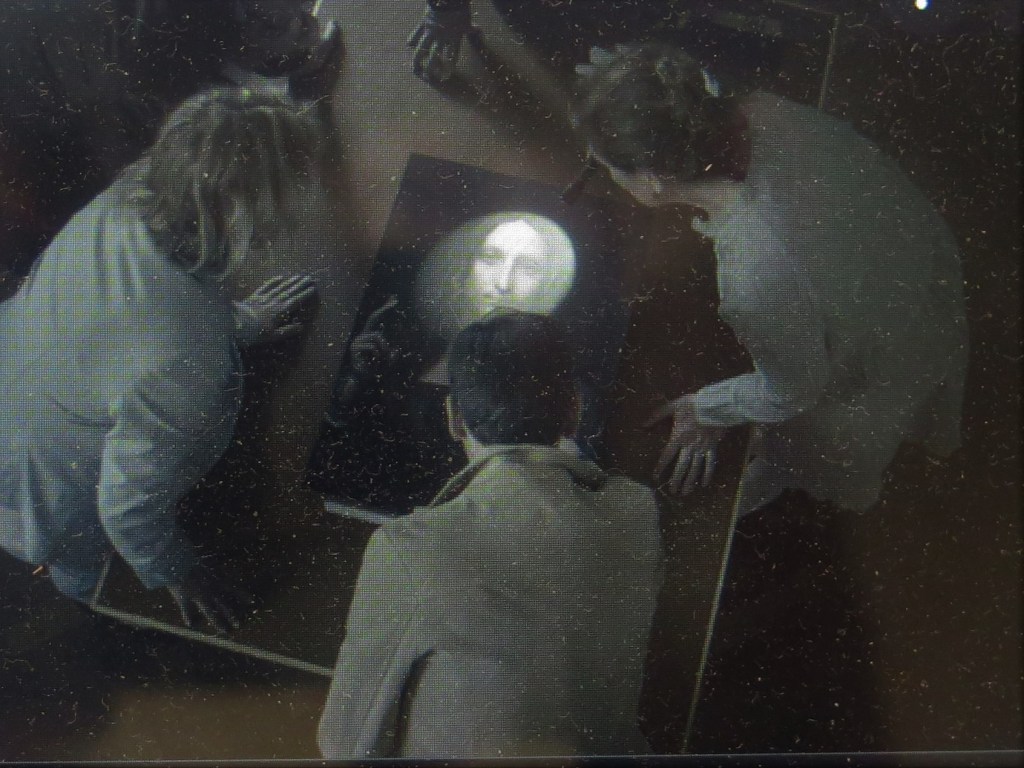

Perhaps conceived with hope initial buyers Alexander Parrish, sleeper hunter, and his friend Robert Simon (an old masters paintings expert) fantasized about what the Mundi was and who painted it. They acted on their conceptualizations, and to satisfy the curiosity of their wallets, they brought the Mundi to top art restorer Dianne Modestini who had partnered with a spot-on expert recently deceased, from whom she had learned. With his assistance, over the years, she had gained expertise and knowledge restoring fine paintings.

As Modestini worked on the Salvator Mundi, she nearly fainted examining the mouth of the figure in the painting. The Salvator Mundi‘s similarities around the right side of the upper lip resembled that of the Mona Lisa. The more she worked, the more she concluded that only one individual could paint in this way: Leonardo da Vinci. As time progressed, the Salvator Mundi in verbal shorthand is referred to by ironist art critics as the male Mona Lisa.

Only eight known paintings are globally attributed to the Renaissance master who was “forward thinking” by about 500 years; among his papers are drawings of space ships and underwater submersibles. He was a scientist, painter, mathematician, inventor and all-around genius. However, that this is a “da Vinci” turning up at auction, like a ghost from the backwaters around New Orleans, remains as implausible and incredulous to some global art experts as unicorns are to empiricists. And these scholars are prepared to deny the work’s authenticity as are those experts who are prepared to defend it to the death as a Leonardo. Belief and faith in the power of money trumps any concern about whether it is a fake that a highly skilled genius painter tossed off and was happy to get some money for.

The problem with any work of fine art, is to establish the provenance and period when it was painted based upon the artist’s technique, any underpainting, the chemicals used to mix the paint as well as the chemical composition of the pigments. Art restorer Dianne Modestini affirms on pain of death that the Salvator Mundi, which sold in 2017 for a record-setting $450 million, is the “lost Leonardo” based upon her understanding of the demonstrated technique and brush strokes.

On the other hand, art critic Jerry Salz who is knowledgeable about the corruption embracing high art sales, auction houses and art galleries who benefit from them is the receptacle of a vast skepticism about the Mundi. Saltz’s demonstrated wisdom is not to be underestimated. Indeed, the art industry has been taken over like other arts industries, for example theater, by the philistines. When money is concerned, auction houses and dealers allow the presence of fakes to take a backseat to money, power and the perception of authenticity, backed by lucid, clairvoyant analyses and explanations.

If you can get away with billionaires offering you hefty sums for works they believe to be authentic, but may not be, who is hurt? If the billionaires are squirreling away their treasures for the purpose of tax evasion in Freeports (tax free airport storage, above the law of all countries) no one will see these fakes anyway and the benefiting institution and billionaire are content. By the time they may have to sell them at a loss, most probably they’ve made twice as much in their corrupt enterprises in the interim. These rich guys are good for art; they are easier than the overhead of collecting subscriber donations and the hard work of charitable fund raising galas to run galleries and museums sometimes at a loss.

An additional factor to consider as to why the allure of wealthy anonymous buyers is so great for the art industry is that running public museums and private art galleries, one must pay exorbitant insurance costs and for security to prevent the little people from thieving works off the walls and reselling it to rich clients who can only display them privately. Better that the art dealers, auction houses and galleries contract with these billionaires who risk purchasing fakes which will most likely be kept in locked rooms in their mansions, Freeports, villas or one of their 15 million-dollar condos neatly situated in favored cities around the world.

The only ones concerned about fakes are the renowned public museums with a rich history of standing by their experts’ knowledge, respected institutions like the Louvre or The Metropolitan Museum of Art or the British Museum. They do not take kindly to displaying fakes or works that are questionable alongside their incredible proven treasures. And perhaps millionaires who don’t have the money to burn on fakes might be concerned. Other than that, billionaires have entered the art world and they are a sure thing for art dealers and auction houses.

In this amazingly instructive film about the upper classes and the corruption of geopolitical wealth, the filmmaker and writers launch off into three thematic threads emphasizing the concept at work which is the “game.” Sectioning off three segments to keep our understanding regular, he amasses a tremendous amount of research in video interviews, archived photos of works and voice overs. These are structured as the “Art Game,” the “Money Game” and the “World Game.”

It is in this discussion of how art is a game, we begin to understand the shadowy dark money world that fuels fakes and authentic pieces alike. Clearly, the filmmaker reveals that one doesn’t engage in this game naively or without experience and circumspection or you will be taken and regret it. How well can you play the game? How well can you game the auction houses and art dealers? How thoroughly can you game yourself?

If you (like the Russian oligarch who purchased the Salvator Mundi from a French Freeport owner are stuffing away your potential fake in Freeport storage units, then art is a safe, untraceable transaction far from Interpol or Vladimir Putin. As an investment it is unrecorded in any bank unless it’s the safely corrupt Cyprus Bank which deals with foreign transactions from corrupt leaders, and practices money laundering.

Such art has no significance to oligarchs, least of all the meaning of “the savior of the world” Salvator Mundi, which may be a joke to the oligarch or afterward MBS who purchased it anonymously as revealed by the FBI art crime bureau. If you truly care about seeing the Mona Lisa or a work of Rembrandt, then the corruption of viewing a fake is monstrous. The reason why the public purchases memberships in museums and donates millions is because they believe what they view is the “real deal.” The fiasco with the sales of the Salvator Mundi and its dubious authentication based on faith has exposed the art industry’s realm of “alternative realities” and the grand con possibilities. Is it or isn’t it a fake? Only the “little people” are self-righteously outraged if what they look at are fakes hanging in the walls of prestigious museums.

Auction houses and galleries and museums have bridged the reality gap into the alternate Donald Trump/Vlad Putin universe (my intimations, not the filmmakers though it is an important theme for our time). These dealers, auction houses and their buyers justify the authenticity or value of the works they sell because they can, especially if the industry trafficks in bullshit. The honest critic or expert is unwanted then, no matter their weight in gold. These themes Andreas Koefoed raises in this profound documentary which is a sweet siren’s warning. And it gives the average museum goer the fodder to ruminate and feel rage at how art has become an untrustworthy commodity, not a historical, cultural legacy.

But billionaires don’t mind the cache that goes with owning various works, for example, MBS who was anonymous until the great reveal by the FBI. Why would the murderer of WaPo reporter Jamal Kashoggi be interested in a painting that means “the savoir of the world?” The thought of his repentance at his villainous acts of killing family and the “traitorous” reporter is laughable.

On the other hand the notoriety of buying it because he could, was alluring. Owning the painting was a way to gain acceptance and prestige. This was so much so that he enticed the curators of the Louvre that he would loan the Salvator Mundi to them as representative of the “Lost Leonardo,” the male Mona Lisa with its provenance and authenticity in doubt. They were interested, until they heard his conditions. They must hang his purchase with the clouds of fakedom wafting off it—next to the Mona Lisa. The publicity alone would be tremendous. In 2011, the UK’s National Gallery displayed the male Mona Lisa with all its warts of uncertainty so that crowds could show up and imagine it was real. For the Louvre to hang the “Male Mona Lisa” next to the “Mona Lisa” would be a validation of it, sort of like riding the Mona Lisa‘s coattails into veracity, truth and art reality.

The Louvre refused. They were not willing to display a potential fake next to their acquisition whose provenance they were certain of. And MBS, annoyed that his offer was spurned, didn’t take them up on allowing them to display the Mundi in a separate room, explaining its restoration and questionable provenance. Of course the film does not go into the irony of a MBS with all his murders on his head, owning the portrait of Christ as the “savior of the world.” It doesn’t have to. The irony is stunning as is MBS’s arrogant longing.

With the exception of museums who display art so that the public can enjoy it, this whole industry is a philistine’s game (the money lenders and buyers who trade). They could care less if David Bowie (no offense meant to this fabulous artist whom I adore) smeared some of his dung on a canvas and signed it and sold it to the highest bidder. Such was the case with Pablo Picasso who became so disgusted with the “trade” aspect of art in the hands of philistines, he used to draw on napkins at restaurants and depending upon whether he liked the wait staff or not, signed the napkin and gave it to them. In some instances, he drew it, signed it and then destroyed it as they hungrily watched. For the artist commercialization of their work is loathsome and welcome, but only if they reap the rewards in their lifetimes, which usually does not happen. However, what can be done if the vultures pick their bones clean after they’re dead and gone? No wonder Banksy rigged the shredding of his “Girl With the Baloon” after the gavel hit in an auction that garnered a record price for his work.

The Lost Leonardo presents a vital perspective of the “art industrial complex” as it were. Who decides what is great art, even if it is potentially fake and not all the experts can agree on its authenticity? The fact that it’s MBS who purchased it for (after a circuitous route of sales from $1175, to $87 million, then $127 + million) $450 million does nothing to establish its credibility. And after the National Gallery exhibited it to great celebration as a da Vinci in 2011, they mired themselves in the smut of gaming when the FBI revealed that MBS purchased it for a price which means it’s now unsaleable and unpresentable if he persists in riding on the coattails of other Leonardo paintings which he could afford, but which should not be sold to him. This is especially so after it has been proven that he ordered Kashoggi to be brutally murdered, an M.O. of his despite his vapid denials.

However, like many billionaires who remain anonymous he worked through an agent. Would the auction house have sold this work to him if they knew he was purchasing it? They know how to play the game. And as a result, they have smeared themselves and the art world with BS which is what the Dutch filmmaker subtly infers in The Lost Leonardo.

This is a film to see, if not for a good look at the painting which is mostly a restoration and therefore, is more Dianne Modestini’s effort than da Vinci’s. It finished screening at Tribeca Film Festival. Look for this beautifully edited and scripted documentary streaming on various channels or perhaps at your favorite Indie theater after its release on 13 of August. Don’t miss this Sony Pictures Classic if you love art and are interested in learning more about the specious and scurrilous art traffickers which unfortunately find dueling interests with renowned museums who cannot afford works of art, after the traffickers bid the works to obscene heights.

‘All These Sons,’ in a World Premiere at Tribeca FF

The World Premiere of All These Sons directed by Oscar-nominated Bing Liu (Minding the Gap) currently screens in Documentary Competition at Tribeca Film Festival. Also, the film is the feature debut of award-winning editor Joshua Altman. Accordingly, to catch this extraordinarily heartfelt work celebrating Tribeca’s twentieth year, make sure to screen it by 20 of June the festival’s end date.

One cannot help but become involved with the young men, their mentors and guides that Bing Liu shadows and interviews in this intimate portrait about two Chicago programs designed to help black communities. Uniquely dedicated to social and personal responsibility, the programs target the South and West sides of Chicago. And they particularly address gun violence. Bing Liu’s portrait is a timely and in depth perspective showing how individuals in these black communities work to re-educate, empower and heal young at-risk black men.

For decades Chicago’s gun and gang violence on the South and West sides garnered national headlines. Sadly, the terrible fact remains that the city government attacks the problem in a limited fashion. First they beef up the aggressive policing measures. Second, the police practice tough enforcement rules. Does police brutality occur? Of course as police use necessary force, sometimes ignoring excessive force which tips over into brutality. Unfortunately, abuses benefit no one. And they create divisions in an already wounded community.

By targeting those who have little opportunity to escape violent neighborhoods, the troubles circle and repeat. Violence never mitigates violence. Instead, it creates hopelessness. Indeed, oftentimes, such short-sighted plans exacerbate violence, a condition that brought Chicagoans to the current state of affairs.

Embedding themselves, Bing Liu and his team shadow two community members who introduce them to the troubled neighborhoods and the programs that help mitigate violence. Billy Moore of Iman and Marshall Hatch, Jr of Maafa, lead effective programs with tremendous effort, love and care. Throughout, filmmakers enlighten us to Moore’s and Hatch, Jr.’s backstory and the backgrounds of those under their care. Indeed, Moore and Hatch, Jr.’s lives qualify them for this work. Having once been on the other end of violence, they know the score and hold nothing back to win over those in their programs.

As the filmmakers view group sessions, personal counseling and interview Moore and Hatch Jr., we understand how Iman and Maafa create a safe space. Ironically, the at-risk youth constantly look over their shoulders for gang vengeance to knock on their doors. Drive-bys in violent neighborhoods kill the innocent and the guilty. Throughout the documentary, we understand that these young men have either killed, been in jail or have lost loved ones as the casualties of turf wars and revenge.

The documentarians approach their research revealing a flare for ethnography. Powerfully, the subjects show how they attempt to change the conditions that produce gun deaths. Thus, the programs select those young men most at risk of being a victim or perpetrator. Before their acceptance, participants must dig deep. Finally, examining their fears and justifications, the young men confront the traumas in their own lives that perpetuate violence.

When Bing Liu and Joshua Altman in cinema verite style follow Charles, Zay and Shamont as they confront their former identities to carve out new personas, we hook into the poignancy and humanity of the process. Realizing the benefit of their own honesty with themselves, participants thrive. Interestingly, they begin to make life-affirming choices. Of course, the daily fight requires they stick with the program and adhere to their mentor’s guidance. If they accomplish this difficult task, they will construct a better future for generations to come. Indeed, their hopefulness and sensitivity redefines and stops them from acting like violent stereotypes. Kudos to the filmmakers for their unfiltered, raw perspective of the participants’ stories. Bing LIu’s honest rendering reveals Charles’, Zay’s and Shamont’s vulnerability, authenticity and will to transform themselves.

All These Sons (a reference to Arthur Miller’s All My Sons) grabs one’s heart and emotions. Indeed, this occurs because Bing Liu and Joshua Altman allow us to hear and see these young men working hard against the cycle they could easily fall back into. Theirs remains a testimony for our time that change can happen. The filmmakers and all subjects in the film relay their powerful message with the faith that fewer may be lost than if the Iman and Maafa didn’t exist.

Finally, this documentary provides a viewpoint rarely seen. It focuses on its participants who speak their truth clearly, succinctly. As a result their bravery and courage to do the hard work of transformation shines.

All These Sons screens in the Documentary Competition category at Tribeca Film Festival 2021. Check for tickets and times by clicking HERE.

‘Shapeless’ Tribeca Film Festival Review

Shapeless, in the Midnighter category at Tribeca Film Festival like its title, remains fairly opaque if one doesn’t recognize the signs of Ivy’s (Kelly Murtagh) illness early on. Cleverly directed by Samantha Aldana and written by Kelly Murtagh and Bryce Parsons-Twesten, the film premiered at Tribeca in the “Midnight” category. Thus, this review will provide no spoiler alerts. Rather than to ruin the eerie emotional dislocations and frightening weirdness the director brilliantly conveys with sound (music selection) and visuals, let Shapeless wash over you when you see this intriguing film.

Indeed, the impressionistic Shapeless centers around this singer/entertainer who must confront her inner demons but doesn’t. By degrees we understand how Ivy’s unconscious undercurrents surface, then retreat, then repeat in ever-widening circular patterns. Tellingly, during Ivy’s isolated moments at home, we gradually understand the entrenched and frightening conflict. However, we never see beyond to the reasons or logic of what she created that fuels her addiction. Because the film avoids the psychological, a huge chasm of uncertainty opens to engulf us in Ivy’s misery. For what she wars against, no cure presents itself. And Ivy doesn’t seek one. She just charges on and moves deeper and deeper into denial.

Fittingly, the Tribeca Film Festival Midnighter takes place in the eerie, atmospheric and elusive city of New Orleans. Known for its jazz backwaters, ghostly tales, haunting sounds, sights and smells and voodoo, the city is the perfect setting. Overarchingly, the film suggests, infers, intimates. No substantive clarity surfaces. We just get to watch Ivy grow more and more debilitated with little explanation. However, Ivy’s choice to sing in clubs contributes to her addiction. Yet, ultimately, her sickness threatens to destroy her singing career. In some ways, dependence on drugs would be easier for her to overcome. What she battles runs so deep that it refashions her into a strange creature. Thus, the fantastic becomes a part of her nature and in turn devours the health and wholeness she would seek.

Finally, Ivy, addicted to self-destructive behaviors on one level becomes further addicted to her fantastic response to those behaviors. Two people, the creature and the woman who seeks salvation, her outer and inner life rock her soul.

The director’s decisions about sound, editing and set design to imbue characterization remain spot-on. And the overall effect unbalances the viewer. Subsequently, as the film enthralls, one becomes more displaced about understanding Ivy. Conclusively, when the viewer realizes the addiction threatens Ivy’s life, yet she can’t overcome it, the shock settles into numbness. This parallels Ivy’s experience. Her situation can’t be that bad. We think as she thinks. Gradually, the viewer swept up in Ivy’s denial, accepts it as circumstance: “it is what it is.” Nevertheless, the director clues in the audience that her condition must not be ignored. And eventually we understand why, though we don’t ever find out the “why” of it.

Based on a true story of Kelly Murtagh’s personal struggle (she also co-wrote the screenplay) Shapeless becomes a cautionary tale of lies, denial, addiction, self-destruction with no resolution. Murtagh’s performance elucidates the hopelessness of those addicted and swept up with illnesses like hers. Her performance in effecting Ivy’s gradual decline in her singing voice which starts out as merely adequate, shines with understanding. Indeed, Murtagh portrays Ivy’s denial and acceptance of what she does to herself with brilliance.

The film should be seen for many reasons. Two key reasons remain Murtagh’s subtle, nuanced portrayal and Aldana’s stylized rendering of Ivy’s condition and its impact on her life. Shapless screens at Tribeca Film Festival. For tickets and times check this link: HERE.

‘Brazilian Modern: The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx,’ The New York Botanical Garden

‘Brazilian Modern” The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx,’ NYBG Installation (June 8-September 29) (Carole Di Tosti)

The New York Botanical Garden is perhaps the most exotic and forward-thinking, theatrical living museum of plants and one of the most magnificent green spaces in all of New York City rivaled only by Central Park. In presenting their largest botanical exhibition ever from June 8 -September 29, 2019, the New York Botanical Garden has achieved a seamless meld with a globally renowned, award-winning Brazilian modernist artist, Roberto Burle Marx (1909-1994).

‘Brazilian Modern” The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx,’ NYBG Installation (June 8-September 29) (Carole Di Tosti)

For this wonderful exhibit, members get to go free on Friday, Member’s Day. See links below to the symposium on Friday.

The influential Brazilian modernist, landscape architect, plant explorer and cultural giant, is deserving of a celebration of his prodigious design work which features examples of the lush gardens he created throughout Brazil and the world. His unique and innovative modernist perspective gave birth to thousands of landscapes and private gardens, including the famous curving mosaic walkways at Copacabana Beach in Rio.The exhibition exemplifies every aspect of his artistry with a curated gallery of his eye-poppying paintings, drawings and textiles.

‘Brazilian Modern” The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx,’ Untitled, 1970 by Roberto Burle Marx, Acrylic on canvas, NYBG Installation, LuEsther Mertz Art Gallery (June 8-September 29) (Carole Di Tosti)

The amazing Burle Marx was a maverick in highlighting the importance of environmental preservation and particularly exotic plant species some found only in Amazonia a good part of which is in Brazil. In the NYBG horticultural tribute to Marx, the exhibition team pulled in experts like Raymond Jungles (FASLA) his protégé who personally knew Marx and worked with him, and those like Edward J. Sullivan, Ph.D., the Helen Gould Shepard Professor of Art History and Deputy Director, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, who has studied Marx extensively and who continues to write about him.

Edward J. Sullivan, Ph.D., the Helen Gould Shepard Professor of Art History and Deputy Director, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, ‘Brazilian Modern” The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx,’ NYBG Installation (June 8-September 29) (Carole Di Tosti)

‘Brazilian Modern” The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx,’ NYBG Installation (June 8-September 29) Raymond Jungles (white hat) foreground/ bottom of the photo with his design behind him (Carole Di Tosti)

Jungles used his expertise and personal experience working with Marx to design the exotic tropical feel and immense grandeur of the installations revealed in three stages of the exhibition. The first is the Modernist Garden with striking, patterned paths that lead through extensive curvilinear planting beds to an open plaza with a reflecting pool backdropped by a wall. This wall design is inspired by a Burle Marx installation in the Banco Safra headquarters in São Paulo. The entire vibrant black, white and grey walkway and colorful, sweeping plantings are framed by spectacular palm trees that tower to their natural heights, many contributed by Jungles’ own personal collection.

Explorer’s Garden ‘Brazilian Modern” The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx,’ NYBG Installation (June 8-September 29) (Carole Di Tosti)

The Explorer’s Garden in the conservatory showcase (not the Palms of the World Gallery whose dome is being refurbished) features the tropical rain forest plants among Burle Marx’s favorites as a bone fide “plant nerde.” These include those he adored, particular exotics which he constantly used in his installations to inform Brazilians about the natural world’s smackdown of diversity in their home country. With this he was constantly building up Brazilian’s sense of home pride.

Water Garden, ‘Brazilian Modern” The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx,’ NYBG Installation (June 8-September 29) (Carole Di Tosti)

Water Garden, Staghorn Ferns-a Burle Marx favorite, ‘Brazilian Modern” The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx,’ NYBG Installation (June 8-September 29) (Carole Di Tosti)

Bromeliads-a Burle Marx favorite, Water Garden, ‘Brazilian Modern” The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx,’ NYBG Installation (June 8-September 29) (Carole Di Tosti)

The Water Garden evinces Burle Marx’s use of plants from a wide variety of tropical regions in his Brazilian designs and throughout the world. The reflecting pool is the natural habitat of temperate water lilies which are blooming in the variety of pastel colors. And it will include the more exotic water lilies that only basque in warm waters of Florida and the equatorial regions; these are of darker purple hues, etc.

‘Brazilian Modern” The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx,’ NYBG Installation (June 8-September 29) (Carole Di Tosti)