Category Archives: Off Broadway

‘The Dinosaurs’ at Playwrights Horizons

In The Dinosaurs written by Jacob Perkins and directed by Les Waters, time stands still yet moves in leaps that are hard to figure out. It takes place in a room where women who are alcoholics meet, form community and establish friendships helping each other through the years. With strong performances that require solo monologues, the characters share experiences and perspectives and enumerate their days of continuing sobriety. The Dinosaurs currently runs at Playwrights Horizons until March 8, 2026.

As the characters set up the neutral unadorned room (scenic design by dots), where they meet, wait for participants to show up and reaffirm the rules of their sessions, we understand this is a female inclusive community. April Matthis as Jane is first to arrive to begin setting up chairs, followed by nervous Buddy (Keilly McQuail), who after a humorous exchange with nonjudgmental Jane, decides she can’t stay. She does show up during the meditation and the end only making a connection with Jane in a layering that makes the time structure hard to divine.

Next, Elizabeth Marvel as Joan enters with the coffee and helps Jane set up. She is followed by Kathleen Chalfant’s Jolly as the longest, oldest member of the group, who brings positivity and warmth with the donuts and scones. Newer member Joane (Maria Elena Ramirez), arrives with gossip about a female teacher. Finally, Janet (Mallory Portnoy)–the appointed time keeper–arrives late and is the first one to share on the topic “coming back,” after their group meditation.

The playwright avoids heavy emotional content related to grief, sorrow, regrets, abuse or violence. Indeed, he avoids in the moment conflict in the plot and character development, with the exception of Joan, Jane and Joane who disagree about feeling empathy for a “lonely” female teacher who has sex with a teen who is “of age.” Jolly provides the down-to-earth humorous perspective as the argument persists then ends once Janet arrives. Interestingly, one would think these are average women of various ages who live regular lives, but for their momentous pronouncement later, during their time to share, that they are alcoholics.

The production spends a good deal of time having Joan, Jane and Jolly set up the room making small talk. Chalfant’s portrayal as Jolly mesmerizes with substance, authenticity and humor, which she clearly infuses with backstory and meaning. In comparison with the other women, Jolly’s character is the most delineated because of Chalfant’s superb, specific performance, as is Marvel’s Joan who reveals why she is an alcoholic toward the end of the play. Otherwise, the characters divulge little else about themselves. This forces the audience to imagine who these women are and why they chose alcohol as their drug and not opiates, barbiturates, food or other addictive elements to anesthetize themselves and escape from life’s “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune;” if indeed, that is why they are alcoholics.

Janet’s metaphoric experience about being driven by a chauffeur she hates and who tells her to throw out the body of a man instead of carrying it around, seems to express her situation of carrying baggage which she eventually throws away in her awake dream state. However, we don’t understand to what she refers and she doesn’t connect the dots. Likewise, the others say little hard evidence about their situations. This adds to a general tiresome opaqueness.

All important personal details are absent, perhaps playwright censored to indicate his characters’ self-censorship. No explanation is given by the playwright, which leaves a huge gap in the ethos of the play. Nevertheless, a picture forms of these characters and the process of their recovery from a disease. However, its horrific effects in their personal lives as they share with their community is never identified. Indeed, the recovery process seems deadening as the women avoid discussing even the difficulty of fighting the urge to taste a drop of their favorite alcoholic beverage.

The characters also avoid discussing the severity of their alcoholism. If the blood never boils with emotion, then not feeling alive removes any impulse to drink. Perhaps keeping a steady deadened state is their key to recovery. How fortunate that they have found other individuals who allow this type of emotional void to be shared. Their tell-tale meditation at the beginning of their meeting indicates what substitutes for feeling and the connection with their feelings.

Notable examples of a separation perhaps disassociation from feelings happen with a few of the characters. Joane’s discussion of finding her son pleasuring an older man in their house seems devoid of an emotional reaction on her part in relation to her drinking. The assumption is that her discovery caused the rift between herself and her son that she describes and perhaps this led to her alcoholism. She and her son never discussed or dealt with her seeing her son with the older man. Did this lead to the dire circumstances that happened later in their lives? Ramirez’ Joane recalls it with dispassion though she takes a moment to breathe revealing the confession is difficult. Her admission that she is revealing it for the first time is groundbreaking.

That her son at fifteen was under the apparent influence of an older man reflective of the current pedophilia reports in the Epstein files is passed over without judgment by Joan or any of the other women. Is this what it takes to recover from alcoholism, this passive, non-reactive state of mind while others are there to just listen?

Joan’s time lapse discussion of the days of her recovery to sixteen years emerges with vitality. A matter-of-fact statement of her number of years without a drink that has seen her in this room with various community members of alcoholics hearing her make comments becomes her milestone. And apparently, during that sixteen year period she had to say goodbye to Jolly who dies and whom she misses. Thus, Jolly’s influence on her own recovery is reduced to less than a minute of time, though counting the years of struggle to maintain sobriety must have seemed an eternity. Unfortunately, there is a grand absence of information. Perkins revels in being opaque. More is needed.

Thankfully, the actors do a yeowoman’s job of leaping over the play’s lack of detail by providing as much of their interior substance as possible. Nevertheless, the lifeblood of theatricality and living onstage is hindered by the playwright’s lack of clarity. Nor is the play’s incoherence at times clarified by Waters’ direction.

Perhaps Rainer Maria Rilke’s quote from Book of Hours which Perkins uses to head up his script might have been spoken aloud by one of the characters in a prelude to The Dinosaurs. The lines of poetry present a lens though which to view each of the characters’ journeys, lifting them to a spiritual plane and revealing the irrelevance of time.

I live my life in widening circles that reach out across the world. I may not complete this last one but I give myself to it. I circle around God, around the primordial tower. I’ve been circling for thousands of years and I still don’t know: am I a falcon, a storm, or a great song. –Rainer Maria Rilke from Book of Hours

The Dinosaurs runs 1 hour 15 minutes at Playwrights Horizons until March 8, 2026. playwrightshorizons.org.

‘Chinese Republicans’ a Sardonic Look at Chinese Women and the Glass Ceiling

A cross section of how Chinese American women have fared in the corporate world is the engaging subject of Alex Lin’s ironic, humorous and ultimately devastating play Chinese Republicans. Directed by Chay Yew, the well-honed production examines personal sacrifice, identity conflicts, and nuanced discrimination (gender, age, cultural). Currently, Chinese Republicans runs at the Roundabout, Laura Pels Theare, Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre until April 5, 2026.

The playwright spins a complex dynamic about Chinese American corporate working women. Yew expertly unfolds the complications among four women of different generations, including one immigrant, working to get her citizenship. During meetings designed to encourage affinity but which actually stir resentments and competitiveness, each of the characters reveals the struggle they face to break the glass ceiling, competing against their less qualified male counterparts. Though the story is unfortunately all too familiar, Lin spikes the interactions with an original, darkly funny approach that resonates with currency.

The production takes off by introducing us to four female suits who work at various upper level positions at Friedman Wallace, as they gather for their “affinity luncheon,” where they meet once a month at a Chinese restaurant. We note ambition, assertiveness and edginess which might as readily be exhibited by any male power-player succeeding in a tough environment. However, these women must obviously work much harder for their success because of internal biases against them culturally as women, and especially as Chinese women. Lin and Yew dance artfully around this gender debility by focusing on cultural elements and details. This strengthens the irony and themes while instructing the audience on elements about the Chinese culture they may not know.

First and most preeminent with experience and knowledge to instruct the younger suits is Phyllis (Jodi Long). She holds little back and uses her irony as a weapon. Ellen, (Jennifer Ikeda), Phyllis’ mentee, has sacrificed having children for her position and plans on becoming partner. Iris (Jully Lee), an immigrant who speaks four dialects, chides the others, especially Ellen on their bad Mandarin and losing touch with their Chinese identity. Lastly, Katie (Anna Zavelson) is the youngest and newest member of the group. Confident and positive about her recent promotion, Katie enthusiastically intones she is excited about their “making a difference.” Then she proclaims, “Come on Asian queens.”

From this luncheon onward, Lin and Yew prove the difficulty for each of the characters to be “Asian queens” in their workplace or their personal lives. Mostly the scenes take place at the restaurant as neutral ground with the exception of the game show farce when Iris ironically shreds Ellen, Phyllis and Katie’s ambitions with irony as part of a fever dream turned nightmare. The side scene after Katie does a turn around and evolves into an advocate for unionizing Friedman Wallace is funny, as she stands in front of the building pumping up a labor rat while the others watch her from the conference room at Friedman Wallace in shock and horror.

How and why Katie reverts to an anti-Republican unionizer from “gun-ho” Asian queen Republican in all its glory involves the corrupt male culture of Friedman Wallace, to discriminatory street violence against Phyllis, to Iris’ immigration hell, to sexual harassment and much more. However, we learn a few twists and turns about each of the characters that add to our admiration of these highly competent women who have endured and suffered nobly, knowing in their bones that not only are the odds stacked against them to ever be at the top, they have strived and sacrificed to what end? A sea of regrets?

The ensemble is uniformly superior. Each portrays their characters with authenticity and a no holds barred approach. As a result the concluding revelations land with poignancy and a powerful kick. The double irony of the evolving meaning of being a Republican is tragic, considering the current face and brand of the MAGA party. Lin neatly slips this information about being Republican into Katie’s development from corporate martinet to human being with a conscience. It’s a reminder to history buffs and salient information for others that political labels are meaningless.

Chinese Republicans fires on all levels of theatricality and spectacle, adhering to Yew’s minimalist, unadorned vision for Lin’s play which focuses on character and themes. Wilson Chin (set design), Ania Yavich (costume design) and other creatives present an attractive backdrop which lends itself to disappearing so the actors are able to live onstage and emotionally, profoundly impact the audience.

https://www.roundabouttheatre.org/get-tickets/2025-2026-season/chinese-republicans

Elevator Repair Service’s ‘Ulysses’ by James Joyce, a Review

Elevator Repair Service became renowned when they presented Gatz, a verbatim six hour production of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby at the Public, as part of the Under the Radar Festival in 2006. Since their remarkable Gatz outing, they have followed up with other memorable presentations. It would appear they have outdone themselves with their prodigious effort in their New York City premiere of James Joyce’s opaque, complicated novel Ulysses. The near three-hour production directed by John Collins with co-direction and dramaturgy by Scott Shepherd, currently runs at The Public Theater until March 1, 2026.

At the top of the play Scott Shepherd introduces the play with smiling affability and grace. He directly addresses the audience, reminding them that “not much happens in Ulysses, apart from everything you can possibly imagine,” and that it happens in the span of a day beginning precisely at 8 a.m,, Thursday June 16, 1904 in Dublin, Ireland. Before Shepherd dons the character Buck Mulligan who appears at the beginning of the novel, he discusses that in the “spirit of confusion and controversy” (labels by critics), Joyce’s day in the life of three characters will be read with cuts in the text. Elevator Repair Service elected to remove Joyce’s text to redeem the time. The cuts are indicated by the cast “fast forwarding” over the narrative.

Collins and the creative team cleverly effect this “fast forwarding” with gyrating, shaking movement and action. Ben Williams’ design replicates the sound of a tape spinning forward. To anyone who may be following along with their own copy of the novel, the “fast forward” segments are humorous and telling. However, the cuts pare away some of the details and depths of character Joyce thought vital to include in his parallel of Dublin figures with the most important characters of the Odyssey: home returning hero Odysseus, long-suffering wife, Penelope, and warrior son, Telemachus.

After Shepherd’s introduction, Ulysses moves from a sedentary reading with multiple actors into a fully staged and costumed production as it progresses through the day’s events principally following Stephen Dedalus (Chisopher-Rashee Sevenson), who represents Telemachus, Leopold Bloom (Vin Knight), as Odysseus, and Molly Bloom (Maggie Hoffman) as Penelope.

The events illuminate these characters, and the cast superbly theatricalizes the novel’s humor, whimsy and farce. Some scenes more successfully realize Joyce’s playfulness and wit better than others. For example when Bloom decides to go to another pub after seeing the sloppy, gluttonous patrons of the first bar, the cast revels in portraying the slovenly, grotesque Dubliners. slobbering over their food. Additionally, the scene where Bloom faces his deepest anxieties shows Knight’s Bloom giving birth to “eight male yellow and white children.” Director Collins hysterically stages Bloom’s “labor” with Knight in the birthing position, legs apart, as Shepherd “catches” eight baby dolls he then throws to the attending cast members.

As costumes and props are added to the staging, we understand Leopold Bloom’s persecution as an outsider and a Jew. Also, wee note Stephen Dedalus as the writer/poet outsider who eventually joins Bloom, a father figure, who Bloom takes home for a time until Dedalus leaves to wander the night alone. Chistopher-Rashee Stevenson portrays the young Dedalus, a teacher whose unworthy friends lead him to drink and misdirection. Dedalus grieves his recently deceased mother and toward the end of the play has a nightmare visitation by her frightening, judgmental ghost.

For those familiar with the novel, the cast becomes outsized in rendering the various Dubliners that Knight’s Bloom and Stevenson’s Dedalus encounter. The dramatization is ultimately entertaining. We identify with Bloom as an Everyman, an anti-hero, who tries to get through the day in peace, while dismissing the knowledge that his wife Molly cuckolds him. Though he hasn’t been intimate with her since their baby Rudy died, he is unsettled that she conducts an affair with Blazes Boylan in their marriage bed at home. Somehow, Bloom has discovered that Molly who is a singer will be meeting with Boylan at 4 p.m. that afternoon. On his journey through the day he avoids confronting Boylan as they carry on with their activities around Dublin.

The ironic anti-parallel to the Odyssey, on the one hand, is that Molly Bloom is far from a Penelope who physically remained loyal to Odysseus, where Molly has an affair. On the other hand, late at night as Bloom sleeps with his feet awkwardly next to her face, we understand that Molly still loves Bloom and is emotionally and intellectually loyal. In her stream of consciousness monologue, seductively delivered by Maggie Hoffman, Molly arouses herself with memories of her relationship with Bloom when they were first together. It was then that she transferred a seed-cake from her mouth to his, sensually expressing her love.

Collins’s staging of the scene is humorous and profound. It defines why Molly has been present in Bloom’s consciousness throughout his strange journey traversing the streets of Dublin until he eventually finds his way home to her bed later that evening.

For those unfamiliar with Joyce’s novel, they will find the events and people a muddled hodgepodge that clarifies then becomes opaque, like a light switch turning on and off. Characters swap places with each other as seven actors take on numerous parts in a sometimes confusing array. Only Bloom, Dedalus and Molly stand out, true to Joyce’s vision for Ulysses for they embody Joyce’s themes about life. Thus, Bloom and Dedalus move through the day with flashes of brilliance, revelation, connection, irony and dread. Their reactions interest us. And Molly Bloom in her ending monologue puts a capstone on the vitality and beauty of a women’s perspective, as she experiences the sensuality and power of love for Bloom through reminiscence.

The costume design by Enver Chakartash reflects the time period with a fanciful modernist flourish that gives humor and depth to the personalities of the characters. For example Blazes Boylan (Scott Shepard) who has the affair with Molly wears a straw hat, outrageous wig and light suit that aligns with his jaunty gait. The scenic design by DOTS is minimalist and functional as is Marika Kent’s lighting design and Mathew Deinhart’s projection design. Most outstanding is Ben Williams’ acute, specific sound design which brings the scenes to life and follows the text adding fun and delight.

By the conclusion the audience is spent following the challenge of recognizing Joyce’s Dublin and the three unusual intellectuals and artists who he chooses to explore. Elevator Repair Service has elucidated the novel beyond what one might endeavor to understand reading it on one’s own. Importantly, they’ve made Ulysses an experience to marvel at and question.

Ulysses runs 2 hours 45 minutes with one intermission at the Public Theater through March 1, 2026. https://publictheater.org/productions/season/2526/ulysses

Kara Young and Nicholas Braun Fine-Tune Their Performances in ‘Gruesome Playground Injuries’

What do people do when they have emotional pain? Sometimes it shows physically in stomach aches. Sometimes to release internal stress people risk physical injury doing wild stunts, like jumping off a school roof on a bike. In Rajiv Joseph’s humorous and profound Gruesome Playground Injuries, currently in revival at the Lucille Lortel Theater until December 28th, we meet Kayleen and Doug. Two-time Tony Award winner Kara Young and Succession star Nicolas Braun portray childhood friends who connect, lose track of each other and reconnect over a thirty year period.

Joseph charts their growth and development from childhood to thirty-somethings against a backdrop of hospital rooms, ERs, medical facilities and the school nurse’s office, where they initially meet when they go to seek relief from their suffering. After the first session when they are 8-year-olds, to the last time we see them at 38-year-olds at an ice rink, we calculate their love and concern for each other, while they share memories of the most surprising and weird times together. One example is when they stare at their melded vomit swishing around in a wastepaper basket when they were 13-year-olds.

How do they maintain their relationship if they don’t see each other for years after high school? Their friends keep them updated so they can meet up and provide support. From their childhood days they’ve intimately bonded by playing “show and tell,” swapping stories about their external wounds, which Joseph implies are the physical manifestations of their soul pain. After Doug graduates from college, when Doug is injured, someone tips off Kayleen who comes to his side to “heal him,” something he believes she does and something she hopes she does, though she doesn’t feel worthy of its sanctity.

Joseph’s two-hander about these unlikely best friends alludes to their deep psychological and emotional isolation that contributes to their self-destructive impulses. Kayleen’s severe stomach pains and vomiting stems from her upbringing. For example in Kayleen’s relationship with her parents we learn her mother abandoned the family and ran off to be with other lovers while her father raised the kids and didn’t celebrate their birthdays. Yet, when her mother dies, the father tells Kayleen she was “a better woman than Kayleen would ever be.” There is no love lost between them.

Doug, whose mom says he is accident prone, uses his various injuries to draw in Kayleen because he feels close to her. She gives him attention and likes touching the wounds on his face, eyes, etc. Further examination reveals that Doug comes from a loving family, the opposite of Kayleen’s. Yet, he may be psychologically troubled because he risks his life needlessly. For example, after college, he stands on the roof of a building during a storm and is struck by lightening, which puts him in a coma. His behavior appears foolish or suicidal. Throughout their relationship Kayleen calls him stupid. The truth lies elsewhere.

Of course, when Kayleen hears he is in a coma (they are 28-year-olds), after the lightening episode, she comes to his rescue and lays hands on him and tells him not to die. He recovers but he never awakens when she prays over him. She doesn’t find out he’s alive until five years later when he visits her in a medical facility. There, she recuperates after she tried to cut out her stomach pain with a knife. She was high on drugs. At that point they are 33-year-olds. Doug tells her to keep in touch, and not let him drift away, which happened before.

Joseph charts their relationship through their emotional dynamic with each other which is difficult to access because of the haphazard structure of the play, listing ages and injuries before various scenes. In this Joseph mirrors the haphazard events of our lives which are difficult to figure out. Throughout the 8 brief, disordered, flashback scenes identified by projections on the backstage wall listing their ages (8, 23,13, 28, 18, 33, 23, 38) and references to Doug’s and Kayleen’s injuries, Joseph explores his characters’ chronological growth while indicating their emotional growth remains nearly the same, as when we first meet them at 8-years-old. In the script, despite their adult ages, Joseph refers to them as “kids.”

Toward the end of the play via flashback (when they are 18-year-olds), we discover their concern and love for for each other and inability to carry through with a complete and lasting union as boyfriend and girlfriend. When Doug tries to push it, Kayleen isn’t emotionally available. Likewise when Kayleen is ready to move into something more (they are 38-year-olds), Doug refuses her touch. By then he has completely wrecked himself physically and can only work his job at the ice rink sitting on the Zamboni.

Young and Braun are terrific. Their nuanced performances create their characters’ relationship dynamic with spot-on authenticity. Acutely directed by Neil Pepe, we gradually put the pieces together as the mystery unfolds about these two. We understand Kayleen insults Doug as a defense mechanism, yet is attracted to his self-destructive nature with which she identifies. We “get” his protection of her because of her abusive father. One guy in school who Doug fights when the kid calls her a “skank,” beats him up. Doug knows he can’t win the fight, but he defends Kayleen’s name and reputation.

The lack of chronology makes the emotional resonance and causation of the characters’ behavior more difficult to glean. One must ride the portrayals of Young and Braun with rapt attention or you will miss many of Joseph’s themes about pain, suffering and the salve for it in companionship, honesty and love.

In additional clues to their character’s isolation, Young and Braun move the minimal props, the hospital beds, the bedding. They rearrange them for each scene. On either side of the stage in a dimly lit space (lighting by Japhy Weideman), Young and Braun quickly fix their hair and don different costumes (Sarah Laux’s costume design), and apply blood and injury-related makeup (Brian Strumwasser’s makeup design). In these transitions, which also reveal passages of time in ten and fifteen year intervals, we understand that they are alone, within themselves, without help from anyone. This further provides clues to the depths of Joseph’s portrait of Kayleen and Doug, which the actors convey with poignance, humor and heartbreak.

Gruesome Playground Injuries runs 1 hour 30 minutes with no intermission through 28 December at the Lucille Lortel Theater; gruesomeplaygroundinjuries.com.

‘The Baker’s Wife,’ Lovely, Poignant, Profound

It is easy to understand why the musical by Stephen Schwartz (music, lyrics) and Joseph Stein (book) after numerous reworkings and many performances since its premiere in 1976 has continued to gain a cult following. Despite never making it to Broadway, The Baker’s Wife has its growing fan club. This profound, beautiful and heartfelt production at Classic Stage Company directed by Gordon Greenberg will surely add to the fan club numbers after it closes its limited run on 21 December.

Based on the film, “La Femme du Boulanger” by Marcel Pagnol (1938), which adapted Jean Giono’s novella“Jean le Bleu,” The Baker’s Wife is set in a tiny Provençal village during the mid-1930s. The story follows the newly hired baker, Aimable (Scott Bakula), and his much younger wife, Geneviève (Oscar winner, Ariana De Bose). The townspeople who have been without a baker and fresh bread, croissants or pastries for months, hail the new couple with love when they finally arrive in rural Concorde. Ironically, bread and what it symbolically refers to is the only item upon which they readily agree.

If you have not been to France, you may not “get” the community’s orgasmic and funny ravings about Aimable’s fresh, luscious bread in the song “Bread.” A noteworthy fact is that French breads are free from preservatives, dyes, chemicals which the French ban, so you can taste the incredible difference. The importance of this superlative baker and his bread become the conceit upon which the musical tuns.

Schwartz’s gorgeously lyrical music and the parable-like simplicity of Stein’s book reaffirm the values of forgiveness, humility, community and graciousness as they relate to the story of Geneviève. She abandons her loving husband Aimable and runs away to have adventures with handsome, wild, young Dominique (Kevin William Paul), the Marquis’ chauffeur. When the devastated Aimable starts drinking and stops making bread, the townspeople agree they cannot allow Aimable to fall down on his job. The Marquis (Nathan Lee Graham), is more upset about losing Aimable’s bread than the car Domnique stole.

Casting off long held feuds and disagreements, they unite together and send out a search party to return Geneviève without judgment to Aimable, who has resolved to be alone. Meanwhile, Geneviève decides to leave Dominique who is hot-blooded but cold-hearted. In a serendipitous moment three of the villagers come upon Geneviève waiting to catch a bus to Marseilles. They gently encourage her to return to Concorde, affirming the town will not judge her.

She realizes she has nowhere to go and acknowledges her wrong-headed ways, acting like Pompom her cat who also ran off. Geneviève returns to Aimable for security, comfort and stability, and Pompom returns because she is hungry. Aimable feeds both, but scolds the cat for running after a stray tom cat in the moonlight. When he asks Pompom if she will run away again, DeBose quietly, meaningfully tells Bakula’s Aimable, she will not leave again. The understanding and connection returns metaphorically between them.

Director Gordon Greenberg’s dynamically staged and beautifully designed revival succeeds because of the exceptional Scott Bakula and perfect Ariana DeBose, who also dances balletically (choreography by Stephanie Klemons). DeBose’s singing is beyond gorgeous and Bakula’s Aimable resonates with pride and poignancy The superb ensemble evokes the community of the village which swirls its life around the central couple.

Greenberg’s acute, well-paced direction reveals an obvious appreciation and familiarity with The Baker’s Wife. Having directed two previous runs, one in New Jersey (2005), the other at The Menier Chocolate Factory in London (2024), Greenberg fashions this winning, immersive production with the cafe square spilling out into the CSC’s central space with the audience on three sides. The production offers the unique experience of cafe seating for audience members.

Jason Sherwood’s scenic design creates the atmosphere of the small village of Concorde with ivy draping the faux walls, suggesting the village’s quaint buildings. The baker’s boulanger on the ground floor at the back of the theater is in a two-story building with the second floor bedroom hidden by curtains with the ivy covered “Romeo and Juliet” balcony in front. The balcony features prominently as a device of romance, escape or union. From there DeBoise’s Geneviève stands dramatically while Kevin William Paul’s Dominique serenades her, pretending it is the baker’s talents he praises. From there DeBoise exquisitely sings “Meadowlark.”

Greenberg’s vision for the musical, the sterling leads and the excellent ensemble overcome the show’s flaws. The actors breathe life into the dated script and misogynistic jokes by integrating these as cultural aspects of the small French community of Concorde in the time before WW II. The community composed of idiosyncratic members show they can be disagreeable and divisive with each other. However, they come together when they attempt to find Geneviève and return her to Aimable to restore balance to their collective, with bread for their emotional and physical sustenance.

All of the wonderful work by ensemble members keep the musical pinging. Robert Cuccioli plays ironic husband Claude with Judy Kuhn as his wife Denise. They are the cafe owning, long married couple, who serve as the foils for the newly married Aimable and Geneviève. They provide humor with wise cracks about each other as the other townspeople chime in with their jokes and songs about annoying neighbors.

Like the other townspeople, who watch the events with the baker and his wife and learn about themselves, Claude and Denise realize the lust of their youth has morphed into love and great appreciation for each other in their middle age. Kuhn’s Denise opens and closes the production singing about the life and people of the village who gain a new perspective in the memorable signature song, “Chanson.”

The event with the baker and his wife stirs the townspeople to re-evaluate their former outlooks and biased attitudes. The women especially receive a boon from Geneviève’s actions. They toast to her while the men have gone on their search, leaving the women “without their instruction.” And for the first time Hortense (Sally Murphy), stands up to her dictatorial husband Barnaby (Manu Narayan) and leaves to visit a relative. She may never return. Clearly, the townspeople inch their way forward in getting along with each other, to “break bread” congenially as a result of an experience with “the baker and his wife,” that they will never forget.

The Baker’s Wife runs 2 hours 30 minutes with one intermission at Classic Stage Company through Dec. 21st; classicstage.org.

‘Archduke,’ Patrick Page and Kristine Nielsen are Not to be Missed

What is taught in history books about WWI usually references Gavrilo Princip as the spark that ignited the “war to end all wars.” Princip and his nationalist, anarchic Bosnian Serb fellows, devoted to the cause of freeing Serbia from the Austro-Hungarian empire, did finally assassinate the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess of Austria-Hungary. This occurred after they made mistakes which nearly botched their mission.

What might have happened if they didn’t murder the royals? The conclusion of Rajiv Joseph’s Archduke offers a “What if?” It’s a profound question, not to be underestimated.

In Archduke, Rajiv Joseph (Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo), has fun with this historical moment of the Archduke’s assassination. In fact he turns it on its head. With irony he fictionalizes what some scholars think about a conspiracy. They have suggested that Serbian military officer Dragutin “Apis” Dimitrijevic (portrayed exceptionally by Patrick Page), sanctioned and helped organize the conspiracy behind the assassination. The sardonic comedy Archduke, about how youths become the pawns of elites to exact violence and chaos, currently runs at Roundabout’s Laura Pels Theater until December 21st.

Joseph’s farce propels its characters forward with dark, insinuating flourishes. The playwright re-imagines the backstory leading up to the cataclysmic assassination that changed the map of Europe after the bloodiest war in history up to that time. He mixes facts (names, people, dates, places), with fiction (dialogue, incidents, idiosyncratic characterizations, i.e. Sladjana’s time in the chapel with the young men offering them “cherries”). Indeed, he employs revisionist history to align his meta-theme with our current time. Then, as now, sinister, powerful forces radicalize desperate young men to murder for the sake of political agendas.

In order to convey his ideas Joseph compresses the time of the radicalization for dramatic purposes. Also, he laces the characterizations and events with dark humor, action and sometimes bloodcurdling descriptions of violence.

For example in “Apis'” mesmerizing description of a regicide he committed (June, 1903), for which he was proclaimed a Serbian hero, he acutely describes the act (he disemboweled them). He emphasizes the killing with specificity asking questions of those he mentors to drive the point home, so to speak. Then, Captain Dragutin “Apis” Dimitrijevic dramatically explains that he was shot three times and the bullets were never removed. Page delivers the speech with power, nuance and grit. Just terrific.

Interestingly, the fact that Dimitrijevic took three bullets that were never removed fits with historical references. Page’s anointed “Apis” relates his act of heroism to Gavrilo (the winsome, affecting Jake Berne), Nedeljko (the fiesty Jason Sanchez), and Trifko (the fine Adrien Rolet), to instruct them in bravery. The playwright teases the audience by placing factual clues throughout the play, as if he dares you to look them up.

History buffs will be entertained. Those who are indifferent will enjoy the fight sequences and Kristine Nielsen’s slapstick humor and perfect timing. They will listen raptly to Patrick Page’s fervent story and watch his slick manipulations. Director Darko Tresnjak (A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder), shepherds the scenes carefully. The production and all its artistic elements benefit from his coherent vision, his superb pacing and smart staging. Set design is by Alexander Dodge, with Linda Cho’s costume design, Matthew Richards’ lighting design and Jane Shaw’s sound design.

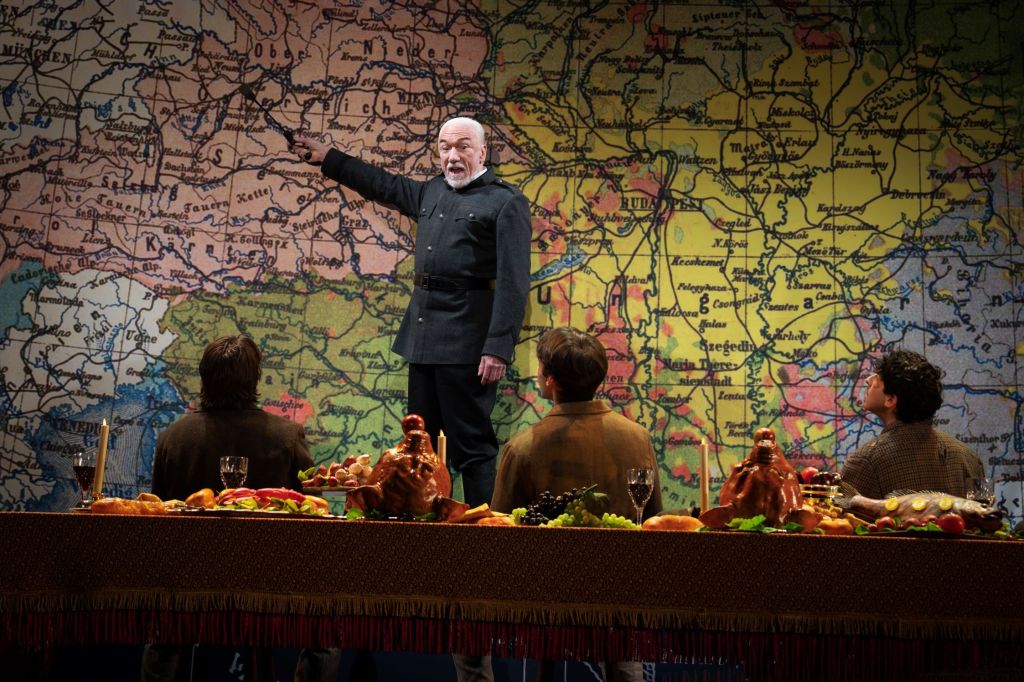

In Joseph’s re-imagining before “Apis” delivers this speech of glory and violence, the Captain has his cook stuff the starving, tubercular, young teens with a sumptuous feast. As they eat, he provides the history lessons using a pointer and an expansive map of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Like brainwashed lap dogs they agree with him when he tells them to. They are inspired by his personal story of glory and riches, and the luxurious surroundings. Notably, they become attuned to his bravery and sacrifice to Serbia, after their bellies are full, having devoured as much as possible.

Why them and how did they get there? Joseph infers the machinations behind the “Apis'” persuasion in Scene 1, which takes place in a warehouse and serves as the linchpin of how young men become the dupes of those like the charming, well-connected Dimitrijevic. From the teens’ conversation we divine that a secret cabal cultivates and entraps desperate, dying young men. Indeed, in real life there was a secret society (The Black Hand), that Captain Dimitrijevic belonged to and that Gavrilo was affiliated with. The playwright ironically hints at these ties when the Captain gives Gavrilo and the others black gloves.

In the warehouse scene the soulful and dynamic interaction between Berne’s Gavrilo and Sanchez’s Nedeljko creates empathy. The fine actors stir our sympathy and interest. We note that the culture and society have forgotten these hapless innocents that are treated like insignificant refuse. As a result they become ready prey to be exploited. The nineteen-year-old orphans have similar backgrounds. Clearly, their poverty, purposelessness, lack of education and hunger bring them to a conspiratorial doctor they learn about because he is free and perhaps can help.

However, he gives them the bad news that they are dying and nothing can be done. As part of the plan, the doctor refers both Gavrilo and Nedeljko to “a guy” in a warehouse for a job or something useful and “meaningful.”

True to the doctor’s word, the abusive Trifko arrives expecting to see more “lungers.” After he shows them a bomb that doesn’t explode when dropped (a possible reference to the misdirected bombing during the initial attempt against the Archduke), Trifko browbeats and lures them to the Captain (“Apis”), with his reference to a “lady cook.”

Why not go? They are starving, and they “have nothing to lose.” The cook, Sladjana, turns out to be the always riotous Kristine Nielsen, who provides a good deal of the humor during the Captain’s history lessons, and the radicalization of the teens, the feast, sweets, and “special boxes” filled with surprises that she brings in and takes out. Nielsen’s antics ground Archduke in farce, and the scenes with her are imminently entertaining as she revels in the ridiculous to audience laughter.

With their needs met and their psychological and emotional manhood stoked to make their names famous, the young men throw off their religious condemnation of suicide and agree to martyr themselves and kill the Archduke to free Serbia. Enjoying the prospects of a train ride and a bed and more food, after a bit of practice, shooting the Archduke and Duchess, with “Apis” and Sladjana pretending to be royalty, they head off to Sarajevo. Since Joseph’s play is revisionist, you will just have to see how and why he spins the ending as he does with the characters imaging their own, “What if?”

The vibrantly sinister, nefarious Dragutin “Apis” Dimitrijevic, who seduces and spins polemic like a magician with convincing prestidigitation, seems relevant in light of the present day’s media propaganda. Whether mainstream, which censors information, fearful of true investigative reporting, or social media, which must be navigated carefully to avoid propaganda bots, both spin their dangerous perspectives. The more needy the individuals emotionally, physically, psychologically, the more amenable they are to propaganda. And the more desperate (consider Luigi Mangione or Shane Tamura or the suspect in the recent shooting of the National Guard in Washington, D.D.), the less they have to lose being a martyr.

Joseph’s point is well taken. In Archduke the teens were abandoned and left to survive as so much flotsam and jetsam in a dying Austro-Hungarian empire. Is his play an underhanded warning? If we don’t take care of our youth, left to their own devices, they will remind us they matter too, and take care of us. Political violence, as Joseph and history reveal, is structured by those most likely to gain. Cui bono? All the more benefit of impunity and immunity if others are persuaded to pull the trigger, cause a riotous coup, release the button, poison, etc., and take the fall for it.

Archduke runs 2 hours with one intermission at Laura Pels Theater through December 21st. roundabouttheatre.org.

‘The Burning Cauldron of Fiery Fire,’ Anne Washburn’s Challenging, Original Play

Known for its maverick, innovative productions, the Vineyard Theatre seems the perfect venue for Anne Washburn’s world premiere, The Burning Cauldron of Firey Fire. Poetic, mysterious and engaging, Washburn places characters together who represent individuals in a Northern California commune. When we meet these individuals, they have carved out their own living space in their own definition of “off the grid.” Comprised of adults and children, their intention is to escape the indecent cultural brutality of a corrupt American society, where solid values have been drained of meaning.

Coming in at 2 hours, 5 minutes with one 15 minute intermission, the actors are spot-on and the puppetry engages. However, the play sometimes confuses with director Steve Cosson’s opaque dramatization of Washburn’s use of metaphor, poetry and song. More clearly presented in the script’s stage directions, the production doesn’t always theatricalize Washburn’s intent. Certainly, the themes would resonate, if the director had made more nuanced, specific choices.

The plot about characters who confront death in their commune in Northern California unfolds with the stylized, minimal set design by Andrew Boyce, heavily dependent on props to convey a barn, a kitchen and more. The intriguing lighting design by Amith Chandrashaker suggests the beauty of the surrounding hills and mountains of the north country where the commune makes its home.

The ensemble of eight adult actors takes on the roles of 10 adults and 8 children. Because the structure is free-flowing with no specific clarification of setting (time), it takes a while to distinguish between the adults and children, who interchange roles as some children play the parts of adults. The scenes which focus on the children (for example at the pigpen) more easily indicate the age difference.

The conflict begins after the members of the commune burn a fellow member’s body on a funeral pyre to honor him. Through their discussion, we divine that Peter, who joined their commune nine months before, has committed suicide, but hasn’t left a note. Rather than to contact the police and involve the “state,” they justify to themselves that Peter wouldn’t have wanted outside involvement. Certainly, they don’t want the police investigating their commune, relationships and living arrangements which Washburn reveals as part of the mysterious circumstances of this unbounded, “bondage-free,” spiritual community.

Nevertheless, Peter’s death has created questions which they must confront as tensions about his death mount. Should they reburn his body which requires the heat of a crematorium to reduce it to ashes? After the memorial fire, they decide to bury him in an unmarked grave, which must be at a depth so that animals cannot dig up his carcass. Additionally, if they keep any of Peter’s belongings, which ones and why? If someone contacts them, for example Peter’s mother, what story do they tell her in a unity of agreement? Finally, how do they deal with the children who are upset at Peter’s disappearance?

We question why they feel compelled to lie about Peter’s disappearance, rather than tell the truth to the authorities or Peter’s mom, even if they can receive her calls on an old rotary phone. Thomas, infuriated after he speaks to Peter’s mom who does call, tells her Peter left with no forwarding address. After he hangs up, Thomas (Bruce McKenzie) self-righteously goes on a rant that he will tear down the phone lines.

When Mari (Marianne Rendon) suggests they need the phone for emergency services, he counters. “Can anyone give me a compelling argument for a situation in which this object is likely to protect us from death because let me remind you that if that is its responsibility we have a recent example of it failing at just that.”

Indeed, the tension between commune members Thomas, Mari, Simon (Jeff Biehl), Gracie (Cricket Brown) and Diana (Donnetta Lavinia Grays) becomes acute with the threat of outside interference destabilizing their peaceful, bucolic arrangements. Washburn, through various discussions, brings a slow burn of anxiety that displaces the unity of the members as they work to hide the truth. What begins at the top of the play as they burn the body in a memorial ceremony that allows Thomas and the group to take philosophical flights of fancy, augments their stress as they avoid looking at hard circumstances.

Fantasy and reality clash also In the well-wrought scene where the actors portray the children moving the piglet they believe is Peter when it reacts to Peter’s belongings, specifically, a poem it chews on. Convinced Peter has been reincarnated and is with them, they take the piglet staunching their upset at Peter’s death by reclaiming and renaming the piglet as the rescued Peter. Rather than to have explained what happened, the commune members allow the children to believe another convenient lie.

This particularly well-wrought, centrally staged scene of the children in the pigsty works to explicate the behavior of the commune members. They don’t confront Peter’s death and don’t allow the children to either. The actors captivate as they become the children who relate to the invisible mom Lula and her piglets with excitement, concern and hope. It is one of the highpoints of the production because in its dramatization, we understand the faults of the commune. Also, we understand by extension a key theme of the play. Rather than confronting the worst parts of their own inhumanity, people close themselves off, escape and make up their own fictional worlds.

Washburn reveals the contradictions of this commune who parse out their ideals and justify their actions “living away from society.” Yet they cannot commit to this approach completely because of the extremism required to disconnect from civilization. As it is, they have a car, they do mail runs and sometimes shop at grocery stores. At best their living arrangement is as they agree to define it and as Washburn implies, half-formed and by degrees runs along a continuum of pretension and posturing.

The issues about Peter’s death come to a climax when Will (Tom Pecinka), Peter’s brother, shows up to investigate what happened to Peter. Washburn ratchets up the suspense, fantastical elements and ironies. Through Will we discover that Peter was an estranged, trust-fund baby who will inherit a lot of money from his grandmother who is now dying. Ironically, we note that Mari who claims she had an affair with Peter and dumped him (the reason why he “left”), is willing to have sex with Will. They close out a scene with a passionate kiss. Certainly, Will has been derailed from suspecting this group of anything sinister.

Also, Will is thrown off their lies when he watches a fairy-tale-like playlet, supposedly created by Peter and the children that is designed to lull the watcher with fanciful entertainment.

In the fairy tale a cruel king (the comical and spot-on Donnetta Lavinia Grays), prevents his princess daughter (Cricket Brown) from marrying her true love (Bartley Booz), also named Peter. The bad king thwarts Peter from winning challenges to gain the princess’ love. Included in the scenarios are puppets by Monkey Boys Productions, special effects (Steve Cuiffo consulting), the burning cauldron of fiery flames with playful fire fishes proving the flames can’t be all that bad, and a beautiful, malevolent, dangerous-looking dragon who threatens.

Once again creatives (Boyce, Chandrashaker and Emily Rebholz’s costumes) and the actors make the scene work. The clever, make-shift, DIY cauldron, puppets and dragon allow us to suspend our judgment and willingly believe because of the comical aspect and inherent messages underneath the fairy-tale plot. Especially in the last scene when Peter (the poignant Tom Pecinka), cries out in pain then makes his final decision, we feel the impact of the terrible, the beautiful, the mighty. Thomas used these words to characterize Peter’s death and their memorial funeral pyre to him at the play’s outset. At the conclusion the play comes full circle.

Washburn leaves the audience feeling the uncertainties of what they witnessed with a group of individuals eager to make their own meaning, regardless of whether it reflects reality or the truth. The questions abound, and confusion never quite settles into clarity. We must divine the meaning of what we’ve witnessed.

The Burning Cauldron of Fiery Fire runs 2 hours 5 minutes with one 15-minute intermission at Vineyard Theatre until December 7 in its first extension. https://vineyardtheatre.org/showsevents/

‘The Other Americans,’ John Leguizamo’s Brilliant Play Targeting the American Dream Extends Multiple Times

After a long career in every entertainment venue from films, to TV, to theater, Broadway, Off Broadway, etc., the prodigious work by the exceptional John Leguizamo speaks for itself. Now, Leguizamo tackles the longer theatrical form in writing The Other Americans, extended again until October 24th at the Public Theater.

Superbly directed by Ruben Santiago-Hudson, the theatrical elements of set design, lighting, costumes speak to the 1990s setting and cultural nuances. The following creatives developed a smart, stylish representation of the Castro household (Arnulfo Maldonado-set design, Kara Harmon-costumes, Justin Ellington-sound, Lorna Ventura-choreography).

Perhaps Leguizamo’s play could be tweaked to tighten the dialogue. All the more to have it shine with blinding, unforgettable truths sounding the alarm for immigrants in this nation. If tightened a bit, the complex, profound play would land perfectly as the unmistakable tragedy it inherently is. However, in its current iteration, Leguizamo gets the job done. The powerful play with comedic elements resonates to our inner core as a nation of immigrants and especially for Latinos.

Clearly, Leguizamo’s characterizations and themes add to the canon of classics that excoriate and expose the corrupted myth of the American Dream as a lie fitted to destroy anyone who believes it. That immigrants make the sacrifices they do to embrace it, is the ultimate tragedy.

Nelson Castro (played exquisitely by John Leguizamo), born in Jackson Heights from Columbian ancestry, embraces the American Dream. His wife Patti (the amazing Luna Laren Velez), from her Puerto Rican heritage, not so much. Patti’s values lead to loving her family and friends with devotion. Daughter, Toni (Rebecca Jimenez), who will marry the solid but nerdy Eddie (Bradley James Tejeda), looks to fit in as a white woman. The younger Nick (Trey Santiago-Hudson) was like his dad and took advantage of others, fiercely competitive. However, an incident changed him forever.

As the play unfolds, Leguizamo deals with the central question. To what extent have the warped values of the predominant culture negatively impacted this Latino family? From his first speech on we note that these twisted values have lured Nelson. The ethos-scam to get ahead-guides Nelson like a veritable North Star. He uses “getting over” as the key reason to provide for his family. This excuse rots everything under his power.

For example, Nelson acts the part of the upwardly mobile success story who always has a deal on the table ready to go. The irony is not lost on us when Nelson hypes a deal with a real estate big wig. Meanwhile, the mogul lives off his reputation for ripping off minorities. Sadly, Nelson admires the mogul’s pluck and con abilities. He ignores how this can potentially harms Latinos.

Mirroring the sick culture and society that values money and material prosperity over people, Leguizamo’s tragic hero tries to wheel and deal to get ahead. Making bad decisions, he overextends himself. Meanwhile, he encourages Nick and Toni to follow his lead. His overweening pride as the patriarch drives him to assume the mantle of a power player. Indeed, the opposite is true. During the process that causes him to fail and lie about it, he compromises his integrity and family’s probity and sanctity. That he willfully blinds himself to the consequences of his beliefs and suppresses his intelligence and good will to fit in, is the final heart breaker.

As in the classic tragic hero, Nelson’s pride also dupes him into a psychotic circularity to believe he has no recourse. Of course he believes the wheels have been set in motion against him by the society’s bigotry and discriminatory values. He should recognize and reject the society that uplifts such values because they support doing whatever necessitates getting ahead. The entire rapacious structure promotes financial terrorism and, whenever possible, it must be rejected. However, Nelson can’t reject it because he can’t help himself from being seduced. Instead, he persists in a prison of his own making, digging his family grave, on a collusion course of self-destruction.

Sadly, he internalizes the society’s inhumanity and makes it his own, a self-hating Latino. Because he adopts this construct because he loathes his immigrant self, he tries to create a new identity apart from his inferior ancestry. Thus, he moves to Forest Hills away from Jackson Heights where he lived “like an immigrant” in a place where cockroaches multiplied.

Finally, as we watch Nelson struggle to assert this new identity in a flawed, indecent, racially institutionalized culture (represented by Forest Hills and what a group of kids did to his son in high school), Leguizamo’s play asserts an important truth for immigrants. Internalizing and adopting the culture’s corrupt, sick, anti-human values is not worthy of immigrants’ sacrifices. This theme is at the heart of Leguizamo’s play. In his plot development and characterizations Leguizamo reveals his tragic hero chases after prosperity and upward mobility. The incalculable loss of what results-losing what it means to be human-isn’t worth it. If one does not weep for Leguizamo’s Nelson at the play’s conclusion, you weren’t paying attention.

To exemplify his themes, Leguizamo uses the scenario of the Castros, an American Latino family. They move from the homey, culturally diverse Jackson Heights to the white, Jewish upscale, racist enclave of Forest Hills. At the outset of the play Nelson, a laundromat owner, awaits his son’s return from a psychiatric facility. Patti has cooked up her son’s favorite dishes. Not only does this reveal her care and concern for her son, her comments to Nelson show her nostalgia for the Latin foods and people of their original Jackson Heights neighborhood in Queens.

By degrees Leguizamo reveals the mystery why Nick was in a facility. Additionally, the playwright brilliantly explores the conflicts at the heart of this family whose parents put their stake in their children, chiefly son Nick to get ahead financially in the Castro business. To recuperate, the doctors partially helped Nick with medication and therapies.

However, on his return home months later, he still suffers and has episodes. Patti sees the change in his dislike of his old favorite foods (symbolic). Not only does he reject meat, he rejects Catholicism and turns to Buddhism. Because a girl he met at the facility influences him, he moves away from his Latin roots. Later, we learn he loves and admires her and they plan to live together. However, he doesn’t look at the difficulties of this dream: no money, no family support.

The family conflicts explode when Nick attempts to be truthful with his parents. In his conversation with his mother we learn the horrific details of the beating he received in high school, why it happened, and how it led to episodes in college. Wanting to move beyond this through understanding, Nick learns in therapy that he must talk to his father. Nelson refuses to acknowledge what happened, and becomes a stalemate to Nick’s progress.

Additionally, his doctor supports Nick’s getting out from under the family’s living arrangements. Inspired, Nick yearns to create a life for himself away from their control to be his own person. Ironically, he follows in his father’s footsteps wanting to create a new identify for himself. Yet, he can’t create this identity unless he confronts the truth of what happened to him in high school and talks to his father. Unless he understands the extremely complex issues at the heart of his father’s tragedy, they won’t move forward together. Nelson must understand that he hates his own immigrant being and has embraced sick, twisted corrupt values which he never should have pushed on his family.

Meanwhile, in a fight with Nelson, Nick demonstrates what may really be happening to him. Though he survived the high school beating with a baseball bat, he most probably suffers from what doctors have come to understand as TBI (traumatic brain injury). With TBI the individual suffers debilities both physically and emotionally. When Nelson questions the efficacy of the treatment Nick received from doctors who didn’t really know what was happening to Nick, Nelson is on the right track. But the science had to catch up to Nelson’s observations.

Meanwhile, the problems relating to Nick needing the right help from his parents and his doctors, Nelson’s financial doom and the future of this Latino family under duress are answered in a devastating, powerful conclusion.

There is no spoiler. Leguizamo elegantly and shockingly reveals this family as a microcosm of the ills of our culture and society. Additionally, he sounds the warning for immigrants. If they don’t recognize and refuse the twisted folkways of the “American Dream,” they may lose their self-worth and humanity for a for a lie.

The Other Americans runs 2 hours 15 minutes including an intermission at The Publica Theater until November 23, 2025. https://publictheater.org/theotheramericans

‘Saturday Church’: The Vibrant, Hot Musical Extends Until October 24th

With music and songs by Grammy-nominated pop star Sia and additional music by Grammy-winning DJ and producer, Honey Dijon, Saturday Church soars in its ambitions to be Broadway bound. The excitement and joy are bountiful. The music and songs, a combination of house, pop, gospel spun into electrifying arrangements by Jason Michael Webb and Luke Solomon, also responsible for music supervision, orchestrations and arrangements, become the glory of this musical. Finally, the emotional poignance and heartfelt questions about acceptance, identity and self-love run to every human being, regardless of their orientation and select gender identity (65-68 descriptors that one might choose from).

Currently running at New York Theatre Workshop Saturday Church extends once more until October 24th. If you like rocking with Sia’s music, like Darrell Grand and Moultrie’s choreography and Qween Jean’s vibrant, glittering costumes, you’ll have a blast. The spectacle is ballroom fabulous. As J. Harrison Ghee’s Black Jesus master of ceremonies says at the conclusion, “It’s a Queen thing.”

However, some of the narrative revisits old ground and is tired. Additionally, the music doesn’t spring organically from the characters’ emotions. Sometimes it feels imposed upon their stories. Perhaps a few songs might have been trimmed. The musical, as enjoyable as it is, runs long.

Because of the acute direction by Whitney White (Jaja’s African Hair Braiding), the actors’ performances are captivating and on target. Easily, one becomes caught up in the pageantry, choreography and humor which help to mitigate the predictable story-line and irregularly integrated songs in the narrative.

Conceived for the stage and based on the Spring Pictures movie written and directed by Damon Cardasis, with book and additional lyrics by Damon Cardasis and James Ijames, Saturday Church focuses on Ulysses’ journey toward self-love. Ulysses (the golden Bryson Battle), lost his father recently. This forces his mother to work overtime. Unfortunately, her work schedule as a nurse doesn’t allow Amara (Kristolyn Lloyd) to see her son regularly.

Though the prickly Aunt Rose (the exceptional Joaquina Kalukango), stands in the gap as a parental figure, the grieving teenager can’t confide in her. Even though he lives in New York City, one of the most nonjudgmental cities on the planet, with its myriad types of people from different races, creeds and gender identities, Ulysses’ feels isolated and unconnected.

His problem arises from Aunt Rose and Pastor Lewis (J. Harrison Ghee). Ghee also does double duty as the master of ceremonies, the fantastic Black Jesus. Though Ulysses loves expressing himself in song with his exceptional vocal instrument, Aunt Rose and Pastor Lewis prevent him from joining the choir until he “calms down.” In effect, they negate his person hood.

Negotiating their criticisms, Ulysses tries to develop his faith at St. Matthew’s Church. However, Pastor Lewis and Aunt Rose steal his peace. As pillars of the church both dislike his flamboyance. They find his effeminacy and what it suggests offensive. At this juncture with no guidance, Ulysses doesn’t understand, nor can he admit that he is gay. Besides, why would he? For the pastor, his aunt and mother, the tenets of their religion prohibit L.G.B.T.Q Christianity, leaving him out in the cold.

During a subway ride home, Ulysses meets Raymond (the excellent Jackson Kanawha Perry). Raymond invites Ulysses to Saturday Church and discusses how the sanctuary runs an L.G.B.T.Q. program. With trepidation Ulysses says, “I’m not like that.” Raymond’s humorous reply brings audience laughter, “Oh, you still figuring things out.” Encouraging Ulysses, Raymond suggests that whatever his persuasion is, Saturday Church is a place where different gender identities find acceptance.

Inspired by the real-life St. Luke in the Fields Church in Manhattan’s West Village, Saturday Church provides a safe environment where Christianity flourishes for all. When Ulysses visits to scout out Raymond, with whom he feels an attachment, the motherly program leader Ebony (B Noel Thomas), and her riotous and talented assistants Dijon (Caleb Quezon) and Heaven (Anania), adopt Ulysses into their family. In a side plot Ebony’s loss of a partner, overwork with running activities for the church with little help, and life stresses bring her to a crisis point which dissolves conveniently by the conclusion.

The book writers attempt to draw parallels between Ulysses’ family and Ebony which remain undeveloped. As a wonderful character unto herself, the subplot might not be necessary.

As Ulysses enjoys his new found persona and develops his relationship with Raymond, his conflicts increase with his mother and aunt. From Raymond he learns the trauma of turning tricks to survive after family rejection. Also, Ulysses personally experiences physical and sexual assault. Finally, he understands that for some, suicide provides a viable choice to end the misery and torment of a queer lifestyle without the safety net of Saturday Church.

But all’s well that ends well. J. Harrison Ghee’s uplifting and humorous Black Jesus redirects Ulysses and effects a miraculous bringing together of the alienated to a more inclusive family of Christ. And as in a cotillion or debutante ball, Ulysses makes his debut. He appears in Qween Jean’s extraordinary white gown for a shining ballroom scene, partnering with Raymond dressed in a white tux. As the two churches come together, and each of the principal’s struts their stuff in beautiful array, Ghee’s Jesus shows love’s answer.

In these treacherous times the message and themes of Saturday Church affirm more than ever the necessity of unity over division, and flexibility in understanding the other person’s viewpoint. With its humor, great good will, musical freedom and prodigious creative talent, Saturday Church presents the message of Christ’s love and truth against a pulsating backdrop of frolic with a point.

Saturday Church runs with one fifteen minute intermission at New York Theatre Workshop until October 24th. https://www.nytw.org/show/saturday-church/?gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=22911892225