Category Archives: Broadway

‘Gary,’ With Nathan Lane, Kristine Nielsen, Julie White, Bringing You Tears in Laughter

Nathan Lane in ‘Gary,’ written by Taylor Mac, directed by George C. Wolf at the Boothe Theatre (Julieta Cervantes)

Gary by Pulitzer Prize finalist for Drama, Taylor Mac and directed by the prodigiously talented George C. Wolfe is WACK! (translation: cosmically brilliant, riotous, sardonic in dark and light) This uproarious “Sequel to Titus Andronicus” (Shakespeare’s first and bloodiest tragedy) is a brutal, intense, intimate play about body parts and indelicate body processes we don’t discuss in polite conversation with The Queen. Rich in themes and characterizations with a clever, twisty plot that surprises, it is also about much more.

To give us a handle in how to approach the mood and tenor of Gary, Carol (the sensational Julie White) comes in front of the once glorious, now shabby curtain and addresses the audience in Shakespeare’s favorite verse, rhyming iambic couplets. As Carol validates the how/why that Titus Androicus deserves a sequel, suddenly she spurts blood from a hole where her throat has been slit during the roiling events of the former play.

The absurdity of her discussion about a sequel that is more craven with gore than the original (while spurting blood) is titanically ironic and bounteously funny! Already, the playwright has set the mood and tenor between the horrific and rambunctious, as Carol’s unsuccessful attempts to stem the red flux poises the audience on a balance beam of tragedy and comedy. If this is the first of the production’s many moments of shock and awesomeness, we’re in for the long and the short of it. Let the rollicking fun begin!

Kristine Nielsen, Nathan Lane in ‘Gary,’ directed by George C. Wolf, written by Taylor Mac (Julieta Cervantes)

Conceivably, after every holocaust of war and massacre, someone has to clean up and set things “straight” again. In her wobbly, blood draining state, Carol brings up the curtain to reveal the debacle of bloodshed at the conclusion of Titus Andronicus. Then she totters off to bleed to death. The mounds and mounds of bodies piled up from the coup are staggering. There is one central mound of bodies to be processed, another pile of processed bodies and another under a sheet. Thanks to Santo Loquasto’s scenic design, everywhere you look there is the attempt to organize rotting flesh in the Roman banquet hall that is a temporary storage place of the dead. These number among them rich and poor, wealthy elites, citizens, officials, soldiers, rulers and others swept up in fierce fighting, civil war, apocalypse. Death does not discriminate.

The feast of death poetically will slide into a feast of celebration, for in a day, the hall will be the site of the new Emperor’s inauguration, another power transition. Into this macabre scene comes Gary (the incredible Nathan Lane who is a riot beyond description) a former clown who juggled live pigeons to little acclaim and no success. Things are looking up for Gary; he has a new job as a servant for the court. But what a job!

Having escaped a near death experience at the executioner’s hand by a lightening stroke of genius, Gary ends up in the hall for he told the executioner he would help tidy up the catastrophe of gore by doing maid service. Little does he realize what cleaning up corpses entails, and when head maid Janice (the magnificent, moment-to-moment Kristine Nielsen) begins to show him, he recoils, reconsiders his choice and redirects his “ingenuity” in a different direction. He will not stay there long; he will rise up and go beyond maid service. He will become a Fool, the wisest of the Emperor’s counsel.

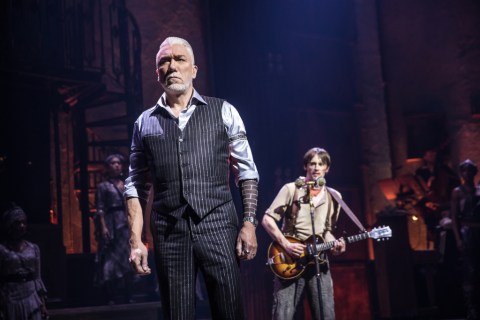

Nathan Lane in ‘Gary,’ directed by George C. Wolf, written by Taylor Mac (Julieta Cervantes)

Meanwhile, Janice must teach loafer Gary the tricks of death’s work in the flesh. Grand experience has inured her to dealing with corpses, for she’s been cleaning up after each of the Roman wars for a long time. And Rome has been battling for decades. As Janice instructs Gary in “cleaning,” her fiendish efficiency at pummeling the gas out of the bodies to extract their farts is Nielsen at her hysterical best. Her antic machinations are real and horrifyingly, and equally LOL humorous, as she drains noxious body fluids showing Gary the difference between siphoning out the blood, and pushing out the poo. Lane’s Gary is priceless in his response to Nielsen’s Janice. The two actors are the perfect counterparts to make us roll in the aisles at their irreverence and seriousness.

From the outset, we understand Mac’s themes of class elitism and domination as the two maids disagree, fight and create their own rank to dominate, even as ridiculous as it is to fight over lead maid and subordinate. From the characters’ quips, jibes, demands, insults and resistances, we learn how beaten down the lower classes are through these prototypical plebeians who are the invisible, the disposable. But then again their disagreement if given latitude may rise to add their corpses to the pile and who then would be left to clean up the mess? The human condition to power over others defies class. There must be something better than this!

Though recovery from his near death experience sent him to a place of hell and damnation with Janice presiding as head monster maid, Gary holds to his enlightened state. He considers; maybe he can save the world and make it better, to stem the tide of wars and bloodshed. His revelation spurs him to attempt to convert Janice to his cause and show her there is something better in life than pumping poo and expelling gas from cadavers.

Julie White in ‘Gary,’ written by Taylor Mac, directed by George C. Wolf (Julieta Cervantes)

But Nielsen’s Janice is an incontrovertible martinet. What’s worse is she’s excellent at her job. She actually takes pride in her efficiency and refuses to revolt against the current social “order” or rise above it. She eschews and belittles Gary’s ambitions. She is insistent about keeping her place at the bottom of the social strata so she can stay alive even if she is a fart expeller. But as Gary questions the “life” she is leading, his presence and argumentative logic wear her down. As she processes the bodies and argues and commands Gary, she erupts with aphorisms and sage comments indicating that perhaps there is a shaking going on in her soul. Perhaps dealing with death has made her wise after all and prone to hope as well.

Carol shocks Gary and Janice joining the scene, having survived bleeding to death in a second near death experience to match Gary’s. She adds to the hilarity by confessing her “sin” that she missed an opportunity to save a life. With distraught fervor, White’s Carol cries out a refrain of her “sin” at pointed moments during the conversation with Janice and Gary. Each time she erupts in a whining cry (no SPOILER ALERT, SEE THE PLAY) she is marvelously, brilliantly funny. And yet, we feel for her and “know” we would not have behaved so cruelly and cowardly as she did. (NOT!) But she, too, can be inspired to change.

White, Lane and Nielsen send up his extraordinary satire on death and the tragedy of the human condition to fear, hate, revenge and murder. And finally, they do what Gary persuades them to, with Janice convinced of the rightness of his enlightened suggestions. The characters create an “artistic coup” and turn the tragedy of humanity (in Titus Andronicus) into an absurd comedy sequel, where the audience laughs at itself and reverses the cycle of hatred, killing and violence.

Nathan Lane, Kristine Nielsen in ‘Gary,’ directed by George C. Wolf, written by Taylor Mac (Julieta Cervantes)

Indeed, Mac and Gary parallel in their intentions, as Gary states in creating his artistic coup, that it’s an “onslaught of ingenuity that’s a transformation of the calamity we got here. A sort of theatrical revenge on the Andronicus revenge.” Thus, this ‘Sequel to Titus Andronicus’ is a comedy bubbling up from a tragedy and the production ends with hope sparked from a clown and mid-wife who had a second chance at life to encourage a maid who was enduring a living death.

Though the pallid, fake, pokey corpses are stripped or dressed as Romans and the setting is in the latter days of the Roman Empire, Mac’s message is clear. This is us! This is now! The more ridiculous-looking and absurd the “cadavers” appear, the more death and war hover in the “unreality” of the piles of staged dummy corpses. In displaying the morbidity of violent effects, the production is precisely pacifist. But it is also a “Fooling.” So…interpret as you will.

Mac, with acute, dark wit creates his new Mac-genre-“Fooling” and reminds us how we “play” with our own mortality and that of others by taking our lives for granted. As invisible as one may feel in light of the culture’s social and political corruptions, there is always hope. There is always something one may do to rise above and use one’s genius to help others. The fact that Gary plans an “artistic revolt” to convert tragedy into comedy suits for our time.

Kristine Nielsen in ‘Gary,’ directed by George C. Wolf, written by Taylor Mac (Julieta Cervantes)

The production rises to the heavens buoyed up by the fabulous talents of acting giants Nielsen, Lane and White shepherded by the superb Wolf. I could write volumes about this work and the humane, sensitive and completely organic performances by Nathan Lane, Kristine Nielsen and Julie White that are “over-the-top” impeccable. I cannot imagine anyone else in their hyper-hilarious, exhaustive, and energetic portrayals.

Wolf and the artistic team display the playwright’s vision and sound the alarm with energetic gusto. Can we luxuriate in continued economic class struggles, power dominations which set up the inequities between the rulers and the ruled? Why must the “inconsequential” and “invisible” under classes continuously put up with what their “betters” have wrought to satisfy their own lusts, while destroying most everyone else and above all themselves in the process? It is a wasted institutional genocide that no one escapes. Are we not better than this? The characters try to prove they are. Bravo to the actors for bringing them to loving life.

This production is profound. Its humor is beyond hysterical, of the type that makes you laugh through your tears, and cry laughing. Its loving stroke will blind you and make you see again. In its irreverence, cataclysmic indifference about the dead, and twitting of the frailties of humanity’s proclivity to murder, exact revenge and make war, it is an indictment of the “upper” classes (the audience is mentioned as part of the court) and vindication of the lower classes who put up with them. In short it is irreverently ingenious. Every arrogant, billionaire narcissist should see this “Fooling.”

Kudos to Santo Loquasto (Scenic Design) Ann Roth (Costume Design) Jules Fisher and Peggy Eisenhauer (Lighting Design) Dan Moses Schreier (Sound Design).

Gary runs without an intermission at the Boothe Theatre (222 West 45th Street) until 4 August. For times and tickets go to the website by CLICKING HERE.

‘Hillary and Clinton’ Starring Laurie Metcalf and John Lithgow

(L to R): Zak Orth, Laurie Metcalf, John Lithgow in ‘Hillary and Clinton,’ directed by Joe Mantello, written by Luas Hnath (Julieta Cervantes)

Hillary and Clinton by Lucas Hnath, directed by the acute, clever Joe Mantello, currently at the Golden Theatre, begins with hypotheticals. Women live their lives in hypotheticals. What Ifs! And this is how the playwright has his character Hillary, who neither looks like nor effects the ethos of Hillary Clinton (played by Laurie Metcalf in a stunning, invested portrayal) opens her discussion in a relaxed “down-to-earth,” “behind the veil” confession to the audience. She posits a “What if?” supposition that there are “infinite possibilities” in our universe.

Hnath wrote the play when Barack Obama was in the full swing of his presidency. Considering what occurred during the 2016 election, Hnath’s play is doubly prescient and its underlying themes resonate more loudly than ever. In 2019 despite #Metoo, perhaps because of it, as much as we’d like to, we cannot pretend that women and men have equality in our culture, especially in light of a Trump presidency which is a throwback to women’s oppression in various forms that echos throughout American History.

For many women, “What if” doesn’t really get a chance to soar to a triumphant conclusion because there are an infinite number of “not possibles” preventing it. The sheer will that is required for women to overstep the “not possibles” is shattering. This is even so in an alternate universe of cultural equanimity, where it is a given that women succeed in obtaining leadership positions because men always lay down their egos and encourage them to do so.

Hnath subtly spins themes about paternalism and gender folkways in his subtle yet not so subtle fictional/nonfictional work. He does this aptly by hypothesizing about one of the most brilliant, competent and ambitious of women in the “free” world living today. Like no other in the political arena, Hillary Clinton embodies the possibilities of power and the smash downs to achieve it. Why is this, Hnath asks sub rosa? He answers this by factualizing his perception of Hillary Clinton’s relationship with Bill Clinton in the service of reminding us about women leadership and competence, about male ego and dominance, about the underlying primal realities of paternalism and male oppression and womens’ attempts to overcome.

At the play’s opening, an always on point Laurie Metcalf as Hillary, posits the probability that on another planet earth somewhere in our universe of “infinite possibilities” there is a Hillary running for the Democratic Party nomination during the 2008 primaries. Hillary, in competition with a man named Barack is losing. With Mark Penn (Zak Orth portrays the shambled-looking, frustrated and stressed campaign manager) Hillary attempts to determine the truth about why she is losing and how she will be able to recoup further losses if she can get more funds to refill her dwindling coffers.

After Mark offers explanations of her loss from his perspective, he indicates that perhaps it is not as bad as she suspects. The Obama campaign actually is daunted by her and has offered an opening for her to be his running mate when he is nominated if she drops out of the next two races and slowly fades away. Hillary interprets this to mean the Obama campaign is circling in for the “kill,” and expresses outrage that she might take such a deal. Despite Mark’s protestations she interprets it to mean she is going down for the count. Mark warns her not to call Bill for help and she promises not to.

Laurie Metcalf, Zak Orth in ‘Hillary and Clinton,’ directed by Joe Mantello, written by Lucas Hnath (Julieta Cervantes)

Twelve hours later, Bill (the wonderful Lithgow) who previously had been kicked off the campaign, shows up in New Hampshire to the starkly minimalistic hotel room (which indicates a lack of funds). When he swears they stayed there before, we consider perhaps this is a backhanded reference to his own campaign in the primaries which he successfully won. In small measure he is forcing her to “eat crow” that she needs him. Then he chides her and expresses his ire at having been thrown off the campaign by Mark.

Their clashes are revelatory. In these discussions they cover a myriad of intriguing subjects: her fear of losing, their lives together, his boredom, her personality, her lack of fire and warmth, that he exhausts her, references to his infidelity and strategies for the upcoming primaries to initiate wins. Some of the subjects are unfamiliar. Others we anticipate because we’ve heard talking heads discuss the Hillary “personality” problem.

Lithgow’s and Metcalf’s focused listening and responding to each other are particularly excellent during Hnath’s dynamic interchanges, well shepherded by Mantello. Importantly, in exploring the fictional/nonfictional complications of a marriage between two brilliant, competitive and ambitious individuals, Hnath reveals the conundrum. They need to be together, but also must be apart in their own identity and autonomy. In their wish to be themselves, they are also the couple in a shared unity and friendship which will end in uncertainty for Hillary and loss for Bill if they separate. The public trust has glued them together as one. Their bond is intangible and ineffable and Hnath particularly suggests this with great sensitivity.

Hnath grounds their arguments, thrusts and parries with homely marriage tropes which we identify and empathize with. They are intensely human, real, warm, vibrant, competitive, loving (their costumes suggest the “all masks off” feel). Underlying all of it are dollops of frustration, wrath, annoyance and fear thrown in for good measure.

Threaded throughout we understand that these two have a profound relationship based on many similarities and attractions based on differences. They have a mutual care and concern that is their greatest grace and their underlying curse. Indeed, Hillary, in anger wishes she could break away from the stench of Bill that follows her. But when he suggests to succeed she must get a divorce, she avers. It is a fascinating moment; for as she states, she knows that many would support this and believe this is the right action for her to take. However, she cannot; she states she will be with him forever. For that he is beyond grateful.

Into this mix is thrust the knowledge of a phone call between Hillary and Obama, during which Hillary accepted Obama’s offer to be his running mate. Upon this everything turns.

Laurie Metcalf, John Lithgow in ‘Hillary and Clinton,’ directed by Joe Mantello, written by Lucas Hnath (Julieta Cervantes)

When Bill steps into the campaign and gives her what she initially requested, he also oversteps his bounds causing rifts between Mark and Hillary. This causes a surprising series of events, one of which includes Barack coming to their hotel room to talk. Barack is portrayed by Peter Francis James in an interesting turn and resemblance to Obama in demeanor and stance. Barack confronts Hillary about the offer to be his running mate and the change in the fortunes of a race, after Bill becomes involved. He also reveals a tidbit of information that landed in his lap, information which will haunt the Clintons in the future.

There is no spoiler alert. You will have to see how Hnath arranges the chips to fall in this climax and how all of what we’ve seen before of their ties that bind, play out.

The play which expands on the premise of “infinite possibilities,” ends on it. From Hillary’s initial flipping of the coin that turns up a 50/50 heads/tails pattern of probabilities, we follow a series of events that decry any possibility of the coin toss dealing Hillary a winning hand. Hnath has brought us closer to explaining why she is not a winner this time, nor a winner in 2016, nor ever unless the earth tilts differently on its axis to produce another earth where Hillary somewhere “over the rainbow” on another earth is president.

Hnath allows us to fill in the unanswerable uncertainties and questions which he leaves open and encourages us to hope for in his poetic “on another earth Hillary is president.” For me this is heartbreaking especially now with the Mueller Investigation revealing a massive Russian warfare campaign to interfere with the election to put Trump in as the president, the results of which we are being deprived of in its full form. Indeed, Hillary lost the 2016 election on planet earth. She did this, perhaps for the reasons suggested intriguingly in the play.

However, Hnath’s powerful work and framing it with the backdrop of probabilities reveals more in what it doesn’t discuss because it was written before we understood what forces were ranging against the United States. Probabilities set up in coin tosses are random. What happened in Hillary Clinton’s 2016 loss (which is never alluded to in the play) is far from a probability. As more of the facts come out (despite the struggle to obfuscate and obstruct the report by the administration) her loss appears to be an inevitability…an inevitability which various illegal forces would go to extreme lengths to bring about.

peter Francis James, Laurie Metcalf, ‘Hillary and Clinton,’ directed by Joe Mantello, written by Lucas Hnath (Julieta Cervantes)

That this production is being presented now at the height of the issues with the release of the Mueller Report Investigation and the DOJ? Well! This is fascinating and curious. And it leads me to this theme: there is more to what appears to be so, what pundits say is so and what “the facts” are depending upon who “owns” them. In Hillary and Clinton, Hnath presents the “What If” and allows us to consider what the character Hillary says about running again at some point. She would like to; she must understand how to get there to win.

This forces us to ponder what happened in 2016 and then the character Hillary brings us back to the coin toss which makes her president on another earth. We go with Metcalf’s Hillary for one second, then are dropped into the pit of reality. She isn’t president. And why not? Because of Bill? Because of her personality? Because of the Clinton Foundation? Because of paternalism? Because she is a woman? Sure!

But!

To my mind, Hillary Clinton’s loss was less about her personality and her relationship and Bill’s “stench” and more about what forces didn’t want her in and why not. All the ultra-conservative social media groups, Russian Intelligence institutions, Russian hackers, Republican Think Tank strategists, elite globalists and like-minded billionaire Americans were poised to prevent her win with systems “ON.” It was a monumental effort that is mind blowing. And very costly.

That’s why Hnath’s character Hillary tossing a coin at the beginning and conclusion of the play is brilliant in theme and profound message. It is frightening, heartbreaking and an eye-opener, however you frame the “What if.” There will never be a “What if” for Hillary. There is no alternate universe, earth or whatever. We must deal with what is and get to work about it.

Laurie Metcalf is gobsmacking; she’s nominated for a Tony, Drama Desk and Drama League for “Best Actress in a Play.” Lithgow is superb. Able assists, Zak Orth and Peter Francis James make this a play you must see. Hillary and Clinton will make you think; it will open your eyes. And as it did for me, it may break your heart.

Hillary and Clinton runs at the Golden Theatre (252 West 45th St.) until 21 July. It has no intermission. You can purchase tickets by going to the website and CLICKING HERE.

‘Tootsie’ is an Indescribably Delicious SMASH HIT

Santino Fontana and Company in ‘Tootsie,’ directed by Scott Ellis, Music and Lyrics by David Yazbek, Book by Robert Horn (Matthew Murphy)

Tootsie, the 1982 film based on the story by Don McGuire and Larry Gelbart and the Columbia Pictures motion picture produced by Punch Productions, starring Dustin Hoffman, is a multi-award winner which is sanctified for its time. The Broadway musical comedy with Music and Lyrics by David Yazbek and Book by Robert Horn has been a long time coming and the wait has been well worth it.

The production starring the likeable and prodigiously talented Santino Fontana is a wondrous addition to this amazing Broadway season. Fontana’s voice is incredible, his dead pan timing bar none, his negotiation of the complexity of this titular role could not be more spectacular. Director Scott Ellis shepherds Fontana and the cast with acuity and grace.

Lilli Cooper and Company in ‘Tootsie,’ directed by Scott Ellis, Music and Lyrics by David Yazbek, Book by Robert Horn (Matthew Murphy)

The Tootsie characterization has been cleverly updated to include superb jokes related to the #Metoo movement. Indeed, what was a maverick fluke in the 1980s film version about gender roles and sexual predation, certainly fits like a glove for our time. Its ridicule of various themes connected with political correctness about gender is cleverly managed. Regardless of left or right we scream with laughter about the self-righteousness of both positions. Tootsie balances on a median between extremes. This is a good thing.

For me, it is a welcome novelty after the mainstream media and social media have become the playland of political, click bait trolls, looking to garner hits and stir controversy. Tootsie is too adroitly written by Robert Horn for that. The only tweets and Instagram hits it will be receiving are for the sustained hilarity and classic comedic situations which bloom like roses in a never-ending summer of delight. I mention roses because the principals will be receiving bouquets for their virtuosity and excellence. Their stellar performances assisted by the equally adroit song and dance talents of the ensemble will run the gauntlet of award season flying high.

Generally, the plot is similar to the film with the major transformation that Michael/Dorothy is an excellent actor who primarily looks for theater work. As in the Michael of the film he is arrogant about his talent, and the conflict’s arc of development sparks when Michael interrupts director Ron Carlisle (Reg Rogers) during the rehearsal of a lousy play. Reg Rogers’ portrayal of the smarmy, oily potential predator who is a Bob Fosse-type without the talent is wonderfully funny.

Reg Rogers and Company in ‘Tootsie,’ directed by Scott Ellis, Book by Robert Horn, Music and Lyrics David Yazbek (Matthew Murphy)

Michael attempts to ingratiate himself with the director Ron Carlisle about his role in the ensemble. Ironically, Dorsey’s narcissism manifests in a twitting of the actors’ dictum: “There are no small parts, only small actors.” Michael suggests there is some confusion about his character’s backstory. When Carlisle tells him he is just in the ensemble and doesn’t require a backstory, Michael is the narcissist in his response.

The director’s outrage is spot-on hysterical and we feel little empathy for Michael who is fired outright. His arrogance and superiority have pushed him over the line as his agent (Michael McGrath) substantiates by firing him in a blow that is a touché! Michael knows he’s a mess, but lacks the power or wisdom to understand what to do about his external crisis, not realizing it’s best solved by changing internally.

Sarah Stiles in ‘Tootsie,’ directed by Scott Ellis, Book by Robert Horn, Music and Lyrics by David Yazbek (Matthew Murphy)

Santino Fontana sings “Whaddya Do” attempting to negotiate his angst at being unemployable. We are unimpressed by his fledgling sign of despair in this song which doesn’t go to the root cause. He must learn much more about himself; he is not there yet. A crucial moment occurs when Sandy visits and informs him about a job she plans to audition for, then has a “slight” breakdown discussing it (“What’s Gonna Happen”). Michael gets the idea to morph into Dorothy Michaels (“Whaddya Do reprise) and audition for the job, having to suppress his male ego in a “female” body to disguise his loathsome face.

To get the role which seems highly unlikely, he’ll be Nurse Juliet in the ridiculous sequel to Romeo and Juliet entitled Julie’s Curse, an outlandish dog of a play that will most probably close opening night. As Michael auditions with “Won’t Let You Down,” Santino Fontana’s voice soars in triumph and realization. During the song, he gives birth to his female ethos and rounds out the personality of Dorothy Michaels housed in a “truck driver’s” body.

(background): Julie Halston, Reg Rogers (foreground): Santino Fontana in ‘Tootsie,’ directed by Scott Ellis, Book by Robert Horn, Music and Lyrics by David Yazbek (Matthew Murphy)

The production never returns to a moderate balance after this, though it has been set-up by a rollicking warm up with Sarah Stiles’ amazing work (more about that below). One reason why the show is a winner is that it glides into the heavens with the organic characterizations, the plot twists, turning points and two love stories (the second one is a ripping hoot thanks to the adorable John Behlmann as naively obtuse Max Van Horn who falls in love with Dorothy/Michael.

The actors’ pacing has been timed with precision to deliver the superbly engineered and crafted one-liners arising from the action and characterizations. The audience never recovers from these, swept up in the hysteria and barely catching their breaths for the next joke. The play is well-structured, building toward the two climaxes, one at the end of Act I and the other near the conclusion of Act II.

John Behlmann in ‘Tootsie,’ directed by Scott Ellis (Matthew Murphy)

The principle theme, that Michael Dorsey has grown as a human being with the help of releasing his feminine side is winsomely revealed as a “la, la, la,” in the film, downplayed for its vitality and power. Santino Fontana does a phenomenal job in bringing this theme to the fore in his solos with his rich sonorous voice. The music strengthens this theme and others. We are reminded that males are ashamed to acknowledge emotions in the company of other males. Today’s retrograde social currents about the bullying “macho male” in the White House who is “cool male” in his indecency makes Tootsie an important show for our time.

A lot of the humor arises with the gender switching. The songs reveal softer scenes as Dorothy must negotiate “his” love for Julie Nichols (Lilli Cooper). The two actors have some wonderful moments as budding BFFs. Their conversations ring true for us today and Julie’s characterization has also been rounded out with profound depth in the writing and in Cooper’s winning portrayal. Julie is a modern, wise woman who does not cave in to the director who attempts to smooze her with his position. She remains steadfast to her career and does not marry.

Andy Grotelueschen in ‘Tootsie,’ directed by Scott Ellis (Matthew Murphy)

The only “feminine woman attitude” the show allows is Michael/Dorothy’s Southern accent and this is an ironic blind. Supported by wealthy producer Rita Marshall (the excellent Julie Halston who pulls out all the stops) Michael/Dorothy takes a stand with the help of the ensemble and Julie. Dorothy Michaels reconfigures the show into one that is a going to be a shining hit (don’t ask how). The producer, Julie and the other actors appreciate Dorothy, though the director is angrily flummoxed. But Carlisle is masking chauvinism in his heart which we infer by his actions toward Julie. However, Carlisle’s producer is a woman who supports Dorothy’s “female” intuition about the play and her gumption to suggest revisions.

Michael’s acting talent and suggestions are given a hearing and used. Juliet’s Curse is transformed into a hit. By the end of Act I, “everything’s coming up roses” and Fontana’s Dorothy pridefully encourages himself by crowing out “Unstoppable.”

The song is a brilliant, humorous irony. Actors through experience, learn not to make presumptions about their future, out of sane superstition. (Sandy takes this to the reverse extreme.) Michael is headed for a fall. Like all of us do at one point or another, he does something to destroy his own success. As he attempts to recover, he digs a deeper hole for himself.

Santino Fontana, Lilli Cooper, ‘Tootsie,’ directed by Scott Ellis (Matthew Murphy)

Roommate Jeff (Andy Grotelueschen) who has been waiting for him to choke, gleefully beats him over the head with his stupidity in the second funniest song of the production, “Jeff Sums it Up” at the top of Act II. Grotelueschen’s performance in this scene (with Fontana as the straight man) is THE MAX! Grotelueschen’s portrayal as the “frustrated” friend Jeff is visceral. His timing is 100%. The effect generates our sidesplitting, roaring laughter. We are down with both Jeff and Michael.

As Michael crashes and burns Greek comedy style., we intuit that the worst is coming. It is only a matter of time before Dorothy’s drag act will be exposed.

I didn’t expect to be so impressed, by this clever reworking of Tootsie, especially with regard to the music. However the songs are damned funny and the music doesn’t draw attention to itself as some composers are wont to do. Indeed, the music serves the story; the lyrics and music meld like white on rice.

Santino Fontana and Company, Tootsie, directed by Scott Ellis (Michael Murphy)

I examined hawk-like whether any songs appeared to just take up space because “after all it’s a musical comedy” and “a song is needed,” etc. NO! Indeed, all the best moments spring from the characters and portrayals. These spur the conflict and create riotous fun. I am hard pressed to critique any of the musical numbers as ancillary or humor killing. A few are extraordinary and a few are memorable pop songs with a beginning, middle and end that doesn’t wander into nothingness.

The two songs you won’t remember (because you’ll be rolling in the aisles) are sung by Michael Dorsey’s friends, his roommate Jeff (Andy Grotelueschen) in the second act and his actress friend Sandy Lester (Sarah Stiles) in the first act. Both songs are organically based in the characterizations. They concern human emotions that are so identifiable that the specifics don’t matter.

Andy Grotelueschen, Sarah Stiles in ‘Tootsie,’ directed by Scott Ellis, Book by Robert Horn, Music and Lyrics by David Yazbek (Matthew Murphy)

For example, in the song “What’s Gonna Happen!” Sandy takes off into a rant about her life as an actress, a state she apparently goes through before auditions. Her imagination terrorizes her into believing in a future and events that don’t yet exist. As she escalates her “crazy,” she explodes. She spews clouds of fear in a musical mixtape of strung together happenings that reach a level of frenzy that is beyond any drug to cure it.

Sarah Stiles is drop dead fabulous. Gobsmacking! We get it! We have been our own terrorists like Sandy, whipping our anxieties to an inner insanity of fear predicting our own nonexistent events. It is our brilliant healing that we find it uproarious to see and hear someone dare to express their delusions ALOUD in a rant more wacko than ours. The song and music are perfect; Stiles’ portrayal is 100 percent. Scott Ellis’ direction and staging elicit this exceptional moment, one of many in this humorously glorious production that kills it again and again.

I have not deeply belly-laughed this much during a Broadway show, except for British productions where the timing is as perfect as it gets. Never during a musical. I have nothing more to say, except you will regret not seeing Santino Fontana, Lilli Cooper, Sarah Stiles, John Behlmann, Andy Grotelueschen, Julie Halston, Michael McGrath and Reg Rogers, every one of them a gem and together, miraculous.

Kudos to Brian Ronan’s Sound Design-I heard every word which is vital for the clever lyrics. Mentions go to David Rockwell (Scenic Design) William Ivey Long (Costume Design) Donald Holder (Lighting Design) Paul Huntley (Hair and Wig Design) Angelina Avallone (Make-Up Design) David Chase (Dance Arrangement for their coherent artistry.

Tootsie runs at the Marquis Theatre with one intermission. For times and tickets, go to their website by CLICKING HERE.

‘Beetlejuice’ Argh! DEMONS! on Broadway

Alex Brightman in ‘Beetlejuice,’ directed by Alex Timbers, Music & Lyrics by Eddie Perfect, Book by Sott Brown & Anthony King (Matthew Murphy)

It is one thing to see the outrageous big kahuna on a tablet, your phone or even on a beautiful Samsung 146″ Modular TV in the safety and security of your living room. It is quite another to witness him live and in person at the Winter Garden Theatre sporting green mold and rot. Yes, that ethos of evil Beetlejuice, Tim Burton’s imminently genius evocation of all things hellish, demonic and flat-out-funny. has come to Broadway. This theatrical extravaganza from soup-to-NUTS is based on the Geffen Company Picture, the titular fan favorite cult film starring Michael Keaton and Winona Ryder (story by Michael McDowell & Larry Wilson).

To see the musical comedy Beetlejuice with Music/Lyrics by Eddie Perfect and Book by Scott Brown and Anthony King, come prepared with crosses, bibles and whatever else it takes to prevent that arch fiend from possessing you. But if you dare risk it, drop all notions of restraint and be prepared to fall into laughter.

The production stars the hysterical and wildly cryptic Alex Brightman as the beloved, infernal monster Beetlejuice. Sophia Anne Caruso is the dour, morbid Lydia, whose belt becomes as brave as her bravura performance to resist marrying the redolent demon costumed in hell’s black and white striped prison garb with greenish tinges (a William Ivey Long costume). Rounding out the principals are Rob McClure as Adam, Kerry Butler as Barbara, Adam Dannheisser as Lydia’s Dad, Charles, and Leslie Kritzer as Delia, the girlfriend.

(L to R): Sophia Anne Caruso, Rob McClure, Kerry Butler in ‘Beetlejuice,’ Music & Lyris by Eddie Perfect, book by Scott Brown & Anthony King, directed by Alex Timbers (Matthew Murphy)

If you are a great fan of Tim Burton’s creative genius and his enlightened vision of the “Netherworld” and the malevolent, frightful spirits that populate it, you will not be disappointed by this glorious iteration that replicates them with the brilliance of twitting itself in the process. The creative designers, director Alex Timbers, ensemble, and even the ushers who escort you down the aisles of the theater (decked out with luminescent green and otherworldly trimmings) have worked prodigiously to make the production shine. And it appears that they have had all the fun in the world doing so. Certainly, the ghosts of Broadway must be happy, for the audience fans of the film, are over the top beside themselves with joy.

There’s a lot to be thrilled about. The puppetry is spectacular thanks to Michael Curry. I was happy to see the sandworm is alive and well arriving in varicolored clouds of sulfur and brimstone. Likewise the Scenic Design by David Korins, Kenneth Posner’s Lighting Design and Peter Hylenski’s Sound Design effects a supernatural realm and crashes it into reality, as does Jeremy Chernik’s Special Effects Design and Michael Weber’s Magic and Illusion Design. Because of their off-the-charts artistry, Beetlejuice’s command of the other worldly in defiance of time and space is satisfying. The haphazard, off-kilter and ultra modern design interiors and appointments of Lydia’s haunted home (from purple to silver and black after Beetlejuice takes over in Act II) are equally smashing.

Alex Brightman’s exuberance, authenticity and zaniness carries the production from the outset solidified by the tenor and mood of the opening number. His easy interaction with the audience is an assist to the funny and brilliant send up of our nascent fears about death and dying which he blasts away by landing that subject squarely in our laps so we might ridicule its “power” with him.

Alex Brightman in ‘Beetlejuice,’ directed by Alex Timbers (Matthew Murphy)

It’s an important opening, well-staged and acutely directed by Alex Timbers. Brightman’s demon clown cavorts; with joie de vivre he stomps down death, mournfulness and morbidity, all the while reminding us we’re dead folks, eventually. He and we are thus driven to rollicking laughter about our immortal presumptions!

Beetlejuice is our Virgil (our guide in the encounters with Morpheus and Legion minus the philosopher’s wisdom and grace) and we walk in the place of Dante (the poet of The Inferno). We are without Dante’s talent, but we retain hope and a penchant for having fun. Indeed, on this amazing journey with the fracasing Beetlejuice we do learn some secrets from him; yes, he reveals a wacky wisdom and astutely nefarious preeminence. This is especially so as he attempts to come back to life through delightful acts of chicanery and cunning misdirection to connive Lydia into marriage. After all, she too has talents; she’s the only one alive who can see him and traverse the realms of life and death.

Beetlejuice’s humorous introduction is an excellent counterpoint to the morbid reality of the scene that follows with Lydia in the graveyard. There, the stereotypes of the cemetery, rainy day, black clothing and umbrellas bring us to what Beetlejuice made us laugh about, Death. But in Lydia’s case, it is horrific, sad. Its fearful aftereffects include the yawning absence of the loved one it snatches away.

As Lydia mourns her mother in song, it is a let down, albeit an appropriate initiation of the play’s actions. Timbers’ staging and William Ivey Long’s costuming are effective in conveying the gravity of the macabre and the brutal “death process” with coffins, funerals and interments so we empathize with Lydia’s loss. Thankfully, there are comical touches which thread humor from the previous scene with Beetlejuice, whom we miss.

Alex Brightman, Sophia Anne Caruso in ‘Beetlejuice,’ (Matthew Murphy)

The plot is morphed from the film with songs to propel Lydia’s emotional moments and to introduce the characters of Barbara and Adam, owners of the house who meet an untimely death that Beetlejuice predicts, as he guides us through the events he directs to get himself resurrected. Kerry Butler and Rob McClure as the young couple become more interesting as they work with Lydia to overthrow Beetlejuice’s insidious intentions spurring on the dynamic conflict of the story.

Sophia Anne Caruso’s portrayal of Lydia is appropriate mouse at the outset as she sings in a near whine at the funeral, overwrought by her mom’s death. She becomes intriguing when she grows furious and insistent that her father Charles (Adam Dannheisser) will not even refer to his wife by name. Her empowerment increases after Charles brings along “life coach” Delia (the LOL Leslie Kritzer) to the house to assist him with his business development sales. She rebuffs Delia and then becomes rebellious when she finds her in her Dad’s bed. Lydia’s rebellion and loyalty to her mother’s memory blossoms into the secondary conflict.

The production builds rather slowly to develop these conflicts and characters; perhaps some of the songs of Act I drag. But if it’s in the service to form a contrast with Beetlejuice whose vibrant presence flings across the stage with unpredictability and surprise, then OK. Importantly, the build-up to the last scene of Act I is a fury of chaos as “Beetlejuice, Beetlejuice, Beetlejuice” usurps control and the house guests are possessed. Most humorous is the duplicitous Delia (Leslie Kritzer) whose Zen vibe flies out the window as she burps in shock, “Day-O,” and sings other phrases of “The Banana Boat Song”with the gyrating ensemble.

Leslie Kritzer, Adam Dannheisser in ‘Beetlejuice,'(Matthew Murphy)

This scene is smashing. We are delighted that Beetlejuice turns the world upside down as he breaks hell loose from its normally restrained moorings in the natural world. The handwriting is on the wall! Clearly, no one in the household stands a chance against him and his Legion. That is, unless Barbara, Adam and Lydia come up with a plan to thwart him.

Act II delightfully catapults one scene into the next as Beetlejuice attempts resurrection and Lydia seeks her mother. The cracked, funny characters of the Netherworld from the film pop out when Lydia travels there to seek her mom. But when she returns, she is anointed to escape hell’s clutches, so she successfully scrambles, racing away from demon football players and the cadaverous Juno (the funny Jill Abramovitz). All this is a power point presentation build-up to the riotous and satisfying last scenes of the play. This is no spoiler alert. You will just have to be brave, ignore the critics and see what happens. Unless you have forgotten how to laugh, you will roll in the aisles with delight.

Alex Brightman in ‘Beetlejuice’ at the Winter Garden Theatre (Matthew Murphy)

The production is a frolic of ingenuity in its reproductions of Burton’s artistic design genius with enhancements that are novel thanks to the show’s creators and artistic team. Importantly, the musical retains the originally stylistic elements that worked to make the film into a cult classic. Fans are especially looking for this.

Where it is uneven is in setting the conflicts in Act I. Some of the songs seem lackluster and overlong. The strength of this musical comedy is in its tantalizing reproduction of the best of the film and how it threads the action and startling themes related to Beetlejuice’s intentions to resurrect himself. How he lets us in on his scheme then guides us through his process is the central focus. Beetlejuice and Lydia hold the strongest dynamic. Their developing characterizations are key. Brightman and Caruso rise to the level required for this with their extensive acting and musical talents, especially in the second act. Brightman’s performance is gobsmacking throughout; Caruso’s voice is sensational. The ensemble rounds out the performances adding fun and humor with great energy.

Beetlejuice is a LOL ride and must-see especially if you saw the film a number of times and appreciate its wit and originality.That is duplicated here with tantalizing twists as it leaps into life so disparate from the digital flats. The production runs at the Winter Garden Theatre on Broadway. For times and tickets go to their website by CLICKING HERE.

‘All My Sons,’ Exceptional Performances Infuse Miller’s Play With Grist and Power

Tracy Letts, Annette Bening in Arthur Miller’s ‘All My Sons,’ directed by Jack O’Brien (Joan Marcus)

Roundabout Theatre Company’s revival of Arthur Miller’s All My Sons speaks with resounding energy about our current time in its themes and characterizations despite its setting 72-years-ago in an America that no longer exists. Directed with acute insight and sensitivity, Jack O’Brien opens the play with the shock of a lightening crash as sounds of thunder dissolve into the droning thrum of a plane. Projected on the curtain we see the visual of a doomed plane speeding toward its demise.

Later, we discover the symbolism. During the fierce storm which destroys a memorial tree in the backyard, Kate Keller (the fabulous Annette Bening) wakes with a nightmare about her son, Larry, a WWII pilot who is MIA. O’Brien adroitly realizes Kate’s nightmare and the storm which destroys Larry’s memorial to foreshadow the coming turmoil in the next day and a half that changes the lives of the Keller family forever.

Tracy Letts, Benjamin Walker in Arthur Miller’s ‘All My Sons,’ directed by Jack O’Brien (Joan Marcus)

This auspicious beginning, however, is quelled by the sunny atmosphere of August in the gorgeous, bucolic, serenity of an upper middle class neighborhood where Joe Keller (the superb Tracy Letts), Kate and son Chris (an emotional, authentic portrayal by Benjamin Walker) reside in peace and plenty. The exquisite set by Douglas W. Schmidt invites with its blooming, well-trimmed wisteria vines regaling a square gazebo and homely, comfortable patio with companionable chairs. There, we imagine that pleasant and lively conversations have taken place over the years. Miller never takes us inside to reveal the intimacies of family interactions, a vital clue to this family. They cannot be intimate with each other for fear of cracking the image they present to each other and themselves.

All the play’s action is “out in the open,” “in plain sight,” an irony filled with contradictions. This living “in the public eye” belies the truth that threads throughout the play in one of Miller’s searing themes. In one form of another, the human condition is to live in lies and rationalizations that mask painful truths. The best of us attempt to confront and work through these to get to the core and evolve to “be better” as Chris suggests. Nevertheless, it is easier for us to keep our miserable truths hidden in the shadows while we live in hypocrisy.

It is this hypocrisy that eats away at the soul and mind in a terrible corruption that eventually destroys. An extension of this theme of the individuals is the theme of a society which lives in hypocrisy in a culture founded on lies. The end result is the rot blooms, the lies abide and the culture no longer distinguishes the difference between facts and obfuscations. The cultural dissolution that occur is not even recognizable to the national body politic.

Tracy Letts, Annette Bening in Arthur Miller’s ‘All My Sons,’ directed by Jack O’Brien (Joan Marcus)

Clearly, Miller reveals this is so for his protagonist Joe Keller and the neighborhood and society which enables Joe to maintain his untenable soul condition. In the backstory, Keller was found guilty of negligence in manufacturing defective aircraft parts that ended up bringing 21 pilots to their deaths. Joe and partner/neighbor Steve Deever, end up serving prison time. Joe appeals and is exonerated, foisting off the blame on Steve who is held accountable for the defective engines being sent out. Steve loses everything including his house and the love of his children who move away as he serves out his prison sentence.

When Joe returns home to neighborhood whispers of “murderer,” he holds his head high, fronts with his new business manufacturing household appliances, makes a ton of money and re-engages the friendship of his neighbors. In a few years he re-establishes the honor and integrity he once held through hard work and a well-meaning, generous, jovial public image. He does all of this for the benefit of his family, and especially for his son Chris who made it out of WWII alive and who will inherit the business.

As the details of the past are revealed, in subsequent acts we gradually understand the family dynamic. Stalwart and unshakable are Kate’s and Chris’ support of Joe during the trial and after feeding into the presumptions that he is a vindicated man with a restored public image. We also note the full blown love relationship Chris has with Steve’s daughter, Larry’s girlfriend, Ann Deever (Francesca Carpanini). Ann moved away after the trial, but writes to Chris and they pledge their love.. She comes to visit Chris, Kate and Joe to solidify their marriage plans with Joe and Kate from whom they’ve kept their love secret. Chris and Ann fear Kate will strongly oppose their marriage because “Larry is alive” and Ann must lovingly wait for him.

As the sunlight shines on Joe and his neighbor Dr. Jim Bayliss (Michael Hayden) and they chat about Ann’s visit, we have no sense of any underlying difficulties. O’Brien’s and the actors’ skill abides in the gradual unraveling of the characters’ consciousness, as each attempts to maintain the intricate bulwark of falsehoods that have carried them through three years of Larry’s absence and Joe’s exoneration, both chimaeras.

Hampton Fluker (foreground) Benjamin Walker, Francesca Carpanini in Arthur Miller’s ‘All My Sons,’ directed by Jack O’Brien (Joan Marcus

Lies are central to this family’s “wholeness” and “health,” as lies are central to America’s dominant “greatness” after the war. In secret, unbeknownst to us until the conclusion, each suppresses their guilt and fear rather than to confront the painful truth head on and bring it out “in the open” to heal. Kate and Joe are stuck in time, mired in the past. Joe recognizes Kate’s insistence that Larry’s “being alive” is a “fantasy.” But he goes along with it to comfort her and himself and avoid any discussion about the possible alternatives.

Likewise, Chris attempts to forge ahead but is locked in his own fears about his brother. It is no small irony that he chooses his brother’s girlfriend to wive and force the issue of Larry’s MIA by bringing her home to mom. Indeed, it is as if he is keeping Larry’s ghost hovering. Ann is the last person his mother will accept as his bride as long as “Larry is alive.” Chris, like his parents, is conflicted and lives with the guilt of his brother’s ghostly presence.

Each of the family members has created justifications; the more the truth threatens, the more elaborate the excuses. Ultimately, these reside in “I did it for you”-Joe, Kate or blaming others, “you made me”-Ann, Chris. Unable to work through the traumas to heal, they tiptoe around each other, wearing masks of goodness, righteousness and faith. The only one who believes these images is themselves.

The neighborhood encourages the family in their fantasies, as the larger society encourages ideologies about America’s goodness. However, as the play progresses, the Bayliss’s (Michael Hayden, Jenni Barber) candidly reveal everyone in the town believes Joe is guilty and Larry was killed by a defective engine. (the truth that Ann brings in a letter is worse).

Eventually, the truth is revealed when George Deever comes to confront them about Joe’s guilt, and Ann reads a letter revealing where Larry is. As George, Hampton Fluker’s, sorrow and yearning to be in the past with the family’s illusions before the hellish incident of negligence happened is beautifully graded and nuanced with poignance. Fluker’s emotional range from judgmental anger, love for the family to, indictment of their duplicity is beautifully developed.

Francesca Carpanini’s Ann approaches this visit with the Kellers as a developing revelation of her “love” for Chris which is founded in loneliness. Carpanini’s emotional range also solidifies her portrayal of Ann’s self-interest and wish to rid Kate of her illusions forever to extricate Chris from Kate’s hold over him. Her performance as the foil and enemy to the family is well rendered.

When Carpanini’s Ann reads the letter, it is a fascinating mixture of emotions. On the one hand she attempts to “help” by revealing the truth, a devastation that will most probably destroy Kate’s well being, but she does it anyway. When it backfires and Chris, Kate and Joe react counter to what she anticipates, she backpedals in an apologetic excuse blaming the family for “forcing her.” She is desperate to recapture Chris, but it’s too late. It is then she understands the length to which the family has unified against the truth which she selfishly used to move things her way.

(L to R): Benjamin Walker, Tracy Letts, Annette Bening, Hampton Fluker, in ‘All My Sons,’ directed by Jack O’Brien (Joan Marcus)

Up to the point of domino revelations at the conclusion, Annette Bening’s portrayal as Kate Keller is a masterpiece of shifting emotions. She is like a tiger who must keep the family together at all costs and will use her cunning against anyone (like Ann or George) who threatens their circle. Thus, as Kate, Bening makes the reality that Larry is alive amazingly palpable. She is the mortar that holds the bricks Chris and Joe fashion into a wall to close themselves off against the truth. The structure is a protection to keep them from looking within to their self-hatreds, guilt and dishonor. If the bulwark of illusions cracks, they would attack and destroy each other; thus, to keep them safe, she sacrifices herself as “the crazy one” by basing her every thought and action around the spin about Larry and Joe.

The truth that George and Ann (ironic it takes Steve’s kids to do this) brings, she attempts to forestall with distractions luring George with love. But it is she who provides the damning piece of evidence to George who hands the sledgehammer to Ann. It is Ann who crashes down the structure that the family has unconsciously built to safe themselves and their self-righteous image to the public.

Annette Bening converts Kate’s belief into the driving force of will which lives and breathes and resurrects Larry’s presence. Bening is stunning in how she effects this, every moment she lives onstage. Her authenticity as she strikes the notes of Kate’s insistence and determination is so starkly alive, it gives Lett’s Joe and Walker’s Chris the charge and fluidity to carry that reality into their own portrayals making them vibrate with authenticity. Her good will toward George turns him off his intentions to indict Joe and the family with his Joe’s terrible abuse of his father Steve.

Tracy Letts, Benjamin Walker in Arthur Miller’s ‘All My Sons,’ directed by Jack O’Brien (Joan Marcus)

How Walker, Letts and Bening adeptly shepherded by O’Brien establish the nexus of Larry’s being both alive and a ghost who haunts all of them is just brilliant. It is the linchpin of the play and all of the action depends upon their getting this right which they do with spot-on intensity.

The more desperately Joe and Chris attempt to move away from Larry’s ghost, the greater Kate digs in (with her telepathy, her reading signs, her dream, her understanding of the Larry’s astrological chart). Chris’ selection of Ann, Larry’s girlfriend, as his future wife and his asking her to visit to end Kate’s faith about Larry. only exacerbates it. Bening and the others are mesmerizing during this dynamic of thrust and parry of unconscious desires to expurgate their guilt and exorcise Larry from their midst. Kate resists Ann’s presence and the marriage from the outset of her suspicions. Letts’ Joe never argues with Kate to counter her about the marriage. Miller makes it clear, Kate is unstoppable in her resistance to the marriage. The irony is that ultimately, Larry stops it. His voice comes in a letter from beyond the grave. And the revelation, one that Kate has feared all destroys the family unity.

Annette Bening in ‘All My Sons,’ written by Arthur Miller, directed by Jack O’Brien (Joan Marcus)

Until the letter Letts, like Bening, is so invested, we are convinced that Joe is exonerated. Even Walker’s Chris cannot hold him accountable as they confront one another after George’s visit in a terrific scene that uncovers their souls. But it is only after Joe reads the letter himself, that he understands what he must do.

This sterling production especially reveals the verities and timelessness of Miller’s play. Joe Keller redeems himself at the end and leaves a legacy Kate knew in her heart was coming, but the pain was so great she couldn’t confront it until Joe does. It is Chris who is left to assemble the pieces of his shattering into a new ethos.

Miller’s tragic elements are the final apotheosis that uplift us to want to be “better than that,” but leave us knowing that if we were in this family’s shoes, we would probably do the same. In the currency of our time, self-righteousness and blaming the “others” has become a profitable boon. Such hypocrisy Miller suggests in Joe’s pointed aria at the end, which he eventually realizes is the last lie that must fall with himself.

The conclusion mounts to a climax of power and poignance and delivers the blow that Miller desires and O’Brien perfectly crashes down on the audience. This tour de force of sensational ensemble work is perhaps the best iteration I’ve seen of this play to date. At its core, the production has delivered Miller’s thematic wisdom from start to finish. The ensemble’s prodigious talent at hitting the bulls-eye with each and every portrayal makes this production the incredible rendering it is.

Kudos to the creative team: Jane Greenwood (Costume Design) Natasha Katz (Lighting Design) John Gromada (Sound Design) Jeff Sugg (Video and Projection Design) Bob James (Original Music) Douglas W. Schmidt (Set Design)

All My Sons runs with one intermission at The American Airlines Theatre on 42nd Street. It is in a limited run until 23rd June. For tickets and times go to their website by CLICKING HERE.

‘Hadestown,’ Broadway’s Tone Poem is an Epic, Illuminating Triumph

André De Shields in ‘Hadestown,’ Music, Lyrics, Book by Anaïs Mitchell, Developed with & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

The ending spirals into the beginning, spirals into the ending. And so it goes in Hadestown, the magnificent production by Anaïs Mitchell (Music, Lyrics, Book), and Rachel Chavkin (Direction and Co-development with Mitchell) currently at the Walter Kerr Theater after transferring from other production iterations at the National Theatre, U.K. and NYTW in New York.

Hadestown is a breathtaking journey, into a phantasmagorical world whose musical pageantry and flickering contrasts between revelatory light and atmospheric darkness vibrate to one’s core. The spiritual themes of the play are rife; the irony of life in death (living to die) and death in life (dying to live) resonate for all time. Mitchell and Chavkin adroitly reshape the well-known love myth of Orpheus and Eurydice to parallel it with the equally compelling love myth of Persephone and Hades: Ancient Greece’s metaphoric visions of the immutable power of death, and the mutability of earthly life reflected in the seasons.

Hermes, the lightening-speed god who operates as our guide, negotiates the realms of the earth and spirit for us. We hop on his quicksilver wings of imagination and go along for the death-defying ride to return to earth wiser, perhaps. As Hermes, the inimitable André De Shields transforms into the phenomenal, captivating messenger.

Eva Noblezada and the Broadway cast of ‘Hadestown,’ Music, Lyrics & Book by Anaïs Mitchell, Developed with & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

With measured grace he combines forceful power with smooth cool. He counsels, philosophizes, warns us in verse and song of an ancient story. It is the story of how the power of love and faith overcome death. And how the fates (the fabulous Jewelle Blackman, Yvette Gonzalez-Nacer, Kay Trinidad in patterned black/white outfits) influence the outcome using fear, doubt and the inherent tragedy of the human condition. Look for their signature song which they beautifully croon to Eurydice who echoes their response (“Any Way the Wind Blows”).

De Shields’ lovable chronicler looks dapper in a silver sharkskin suit with slivery slips on his sleeves which suggest wings courtesy of Michael Krass’ symbolic, well-thought out costume design. (Krass’s costumes enhance the characterization and themes throughout.) De Shields’ moves and manner are so easy, we risk the mysterious train ride with him through light and darkness on the journey to Hadestown and are introduced to all those who play a part in his chronicle of gods and men, life and death, material and supernatural forces (the “Road to Hell”).

(L to R): Jewelle Blackman, Kay Trinidad Yvette Gonzalez-Nacer, Music, Lyrics & Book by Anais Mitchell, Developed with & Directed by Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

Mitchell’s and Chavkin’s amazing reconfiguration of these myths is powered by vibrant, musically diverse and multilayered songs and spoken verse. These combine to reveal how climate change has gravely misaligned the world that the characters live in. Chavkin and Mitchell evoke fitting metaphoric parallels with the myths of mutability and immutability. Orpheus and Eurydice become central characters interwoven in the fabric of the play: its action, conflicts, arc of development, symbols, themes.

On the material plane, the situation is dire. Upended by fires, floods and extreme cycles of heat and cold with storms that are off the categorical charts, the earth provides no succor for its inhabitants, many of whom are destitute and dying. Forced into a gypsy lifestyle, outrunning starvation and weather extremes as resources become scarce, migrants like Eurydice (the golden voiced Eva Noblezada) face an arduous, spooky ride to Hadestown unless they manage to get to the next day. Theirs is an existence of slow starvation, chronic sickness, sexual abuse and torment.

Eva Noblezada, Reeve Carney, André De Shields, Music, Lyrics, Book by Anaïs Mitchell, Developed with & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

For the haves like Orpheus (Reeve Carney’s naiveté, “touched” grace and beautiful tenor shine throughout) whose ancestor is a Muse and whose life is anointed by the protection of Hermes, the situation is less bleak. Orpheus has a roof over his head and a menial job in a haunting, ambience-rich, New Orleans-like jazz club, a way-station where the customers are soothed by the music of Dixieland before they continue on with the struggles of their miserable lives or elect to ride the train on the “Road to Hell” and get off at the last stop, Hadestown..

It is in this charged, atmospheric, (the lighting is superb thanks to Bradley King) jazz/R & B/folk/pop joint, Orpheus encounters the stunning, waif-like Eurydice, who is blown in by the Fates (“Any way the Wind Blows”). He falls for her and attempts to entrance her with a song of love that will right the world and return spring and abundance to the planet. But Eurydice’s knowledge of the dire, doomed existence of humanity runs deep. She confronts him with the facts of starvation and reality of life’s sorrows. She asserts his song has no power. But as he sings, the generating force of the anointed melody stirs her. She realizes its greatness and tells him to finish the song. He reassures her of his love and vows the song will establish a shared brotherhood and prosperous peace (“Come Home With Me,” “Wedding Song”).

Mitchell and Chavkin use the evocation that Orpheus’ love song is an ancient melody Hermes gave him when he was young. They dovetail this concept into the second love myth of Persephone and Hades. “Epic I” sung by Orpheus and Hermes, reveals how the gods’ love “made the earth go round” and established the beauteous seasonal balance that few remember now that their world is dying. The implication is that Orpheus’ supernatural song will return the earth to its former glory, and Persephone will be present the full six months of the year to celebrate her powers above ground (“Livin’ It Up On Top”).

Amber Gray in ‘Hadestown,’ with the company, Music, Lyrics & Book Anaïs Mitchell, Developed & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

With hope and determination that he can succeed because, as Hermes says, “he’s touched,” Orpheus and Eurydice pledge their forever love in the lyrical “All I’ve Ever Known.” Eurydice forgets the reality of starvation in the warmth of Orpheus’ embrace as she basks in the beauteous spring that Amber Gray’s feisty, ebullient Persephone brings, however, briefly.

The seasons shorten incrementally, reflecting the indelible impact of global warming and Hermes’ injunction of “times being hard.” Persephone’s wine celebration is cut even shorter. Hades’ ride to bring Persephone back to the underworld is foreshadowed in the gyrating rhythms, enthralling melodies, sharp lyrics of “Hadestown,” In this memorable titular song, Hermes, Persephone and the entire company indicate what’s causing the earth’s doom as they illustrate in movement and song what Hadestown is like in its symbolic reflection of its impact above ground.

The themes and plot development merge seamlessly as the love stories meld. Hades, the brooding mover and shaker and oppressed Persephone are brought into focus with intriguing twists. Overwhelmed with anxiety and the stress about growing his powerful underworld empire (precious metals, oil, and attendant industries), Hades has forgotten his youth and the joy of his love for Persephone. He’s dour, commanding; she’s his bored, unhappy, trophy wife. The underlying humor is ironic. He is supposed to be the terrifying, sexy god of the underworld and his wife is, in effect, kicking him out of her bed. Fearing he has lost her, Hades brings Persephone back to Hadestown earlier and earlier triggering weather extremes as the earth cannot adjust (“Gathering Storm”).

Eva Noblezada and the Broadway cast of ‘Hadestown’ Music, Lyrics & Book Anaïs Mitchell, Developed & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

When Persephone leaves, weather devastation returns. Eurydice suffers her former hellish grind and panic. She searches for food and firewood, losing patience, dismissing Orpheus’s vows. While Orpheus feverishly works on the song (“Epic II”) she wanders in weariness and hunger. The conflicts intensify. The lure of Hadestown, the world apparently more stable than the cataclysmic earth in the song (“Chant”) trenchantly reveals the strident tensions between Orpheus and Eurydice.

Eventually losing her will to survive, doubting Orpheus’ ability to care for her, Eurydice becomes susceptible to Hades. He finds her fascinating because Persephone has cast him aside (“Hey Little Songbird”). When he offers Eurydice safety, security and freedom, she considers a visit to Hadestown for a bite to eat would be better than waiting for Orpheus in pain. What should she choose? Security and reliability below or starvation, slow torture and uncertainty above. Whether now or in the future, either decision will result in the final stop of her existence in Hadestown. What she does not consider is her will. It is one thing to struggle to survive, dying in the process. It is another to choose to die because it is too tough to go on.

Though this differentiation is inferred in the play, Greek Mythology carries it further. Souls who made good/beneficial choices on earth (they did not commit suicide) went to the Elysian Fields where they played all day: an equivalent of Paradise. Other souls who made harmful decisions were given their just due in the underworld. The souls in Hadestown fall into the latter category, laboring in the toil of the mines forever, in Mitchell’s and Chavkin’s version.

Reeve Carney and the Broadway cast of ‘Hadestown,’ Music, Lyrics & Book Anaïs Mitchell, Developed & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

As Eurydice considers her options, the Fates influence her with the fabulous, rhythmic “When the Chips Are Down.” (“Aim for your heart, shoot to kill, if you don’t do it, then the other one will”). Eurydice chooses her destiny, allowing material necessity and her flesh to overwhelm her. As she embraces Hadestown’s certainty, she cries out for Orpheus as the Fates admonish the audience that they would do the same as she, if they were in her shoes, in the superb song (“Gone, I’m Gone”).

Eurydice affirms she’ll return (“Wait For Me”) then travels to the underworld lowered into the darkness as ominous clouds of smoke billow up with intimations of flames and intense heat. Orpheus finishes his song, but it’s too late; Eurydice has gone into hell. Hermes guides him along a secret alternate route to Hadestown as Hermes, Orpheus, Fates and the ensemble sing that Orpheus comes for her in the lyrical, powerful ending of “Wait For Me.”

These scenes are uniquely staged, with dynamism and excitement; the lighting enhances throughout. The tension builds to the final revelatory scene in Act I which uncovers Hades’ terrifying realm. The revolving platforms move clockwise and counterclockwise as the ensemble and Orpheus move in the opposite direction. Time reverses and changes course as Orpheus walks with fierce determination to the underworld.

Patrick Page (foreground) Reeve Carney (background) in ‘Hadestown,’ Music, Lyrics & Book Anaïs Mitchell, Developed & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

The circularity of movement is rich with profound meaning. For example, we make repeat wrong decisions, doing the same thing over and over again with dire consequences This theme suggests the oblivion of Hadestown, (its boring factory sameness) and the waning vitality of Hades. His repeated bad decisions result in the imprisonment of himself, his workers and Persephone, the goddess of change, who abhors the drudgery of the same old same old. Hades has so brainwashed himself, he’s convinced they are free while they are in oblivion as they work like slaves (today’s corporate erosion of worker’s rights…see the film American Factory)

The pounding, thematically “earth-shattering” brilliant song, “Why We Build the Wall” sung by Hades, Persephone and the company is a sardonic paean to wall builders everywhere. The song is Hades’ stubborn justification for his misery, self-torment and the loss of his youth while amassing an empire. By building the wall he and workers he refers to as his “children” keep out the fear of uncertainty and want. They are secure in their never-ending work as they war against deprivation. What he seeks to avoid, he brings upon the entire planet in a self-fulfilling prophecy swaddled by fear. There is only one way to break down the wall: restore Hades’ and Persephone’s love. His fear of losing her will end and he’ll allow her to restore the earth in the natural balance of the seasons. Orpheus must sing his anointed, ancient love song to restore Hades to himself and Persephone, and restore Eurydice to his arms and life.

Patrick Page, Amber Gray in ‘Hadestown,’ Music, Lyrics & Book Anaïs Mitchell, Developed & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

As Hades, Patrick Page’s eminence is superbly realized in his demeanor, walk, voice and appearance. Page’s Hades is a charismatic warlord who sports his sleek brand of “mellow cool” in a gangster-ish pin stripped suit and styled comb-up. His organic, spot-on portrayal makes him human and empathetic. Though he is a god, he fears his adoration of Persephone (“Chant”) is jealous of her absences, and looks for comfort in someone new (“Hey, Little Songbird”). Page’s portrayal is spot-on, mesmerizing.

Amber Gray’s Persephone is an energetic, sun-filled presence. She blooms with razz-ma-tazz vitality above ground but turns it around as an upside down gal in the bleak underworld appropriately dressed for a perpetual funeral. Like the rest of the principals in the ensemble, she is just smashing. Carney’s Orpheus and Noblezada’s Eurydice sing with the lyricism inherent in their gorgeous vocal instruments. They permeate their songs in the second act with soulful, aching beauty, breathing life into the score and lyrics. But then so do Hermes/De Shields (Wow!) Hades/Page (Good gracious!) Persephone/Grey (Yes, ma’am!)

Reeve Carney, Eva Noblezada in ‘Hadestown,’ Music, Lyrics & Book Anaïs Mitchell, Developed & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

Act II brings the fullness of the plot development, themes and characterizations/gods/lovers that Hermes has so familiarized us with, we’ve come to adore them as family. The song lyrics and music are standouts and build upon what’s been threaded before. You will walk away humming the tunes, drumming the beats. Orpheus’ journey to Hadestown is paced frenetically, with foreboding danger as he moves with stylized grace through his mind of doubt and fear. The use of lighting is sensational and thrilling especially during this sequence (thanks, Bradley King). And at the end, well it’s De Shield’s moment. He stands rooting us in mankind’s tragic history, as the ensemble joins him in soaring song that will be sung over and over again. Ineffable.

This is the type of production that is so jeweled, one will appreciate it in the second seeing or third. You will catch nuances here, symbols there, effects, songs, movements, so much of what your sleight of mind may have missed the first or second time around. All of it is soul careening. This rare production thrums with poetic grace and ancient rhythmic currents that resonate profoundly, irrevocably with life. And occasionally what peers out at us in this play from the other side reminds us of…

Kudos to the creatives who measured the symbols of characterization and themes to synergistically meld them with stylistic, adroit artistry into the play’s fantastic spectacle: Rachel Hauck (Scenic Design) Michael Krass (Costume Design) Bradley King (Lighting Design) Nevin Steinberg, Jessica Paz (Sound Design) Hudson Theatrical Associates (Technical Supervision) Michael Chorney, Todd Sickafoose (Arrangements and Orchestrations).

The music and lyrics are unparalleled, thrilling, coherent. Mitchell and Chavkin, the ensemble and creatives have wrought a divine work for the ages. Surely it is a multiple award winner. Hadestown runs with one intermission at the Walter Kerr Theater (219 West 48th St.) For tickets go to their website by CLICKING HERE.

‘Burn This,’ Sparking Flames Between a Smoldering Adam Driver and Cool Keri Russell

Keri Russell, Adam Driver in ‘Burn This,’ by Lanford Wilson, directed by Michael Mayer (Danielle Levitt)

Part of the fun of watching Lanford Wilson’s characters in Burn This includes noting their particularity, their measured “normalcy,” their zany, hyped-up incredulity. Concisely directed by Michael Mayer for authenticity and humorous grist, Burn This in its New York City revival drifts, flares up, subsides, then rages. The characters circle each other, collide, implode, retreat with tenuous watchfulness, then boil over, coursing the play to an uplifting conclusion.

What makes this an intricate production is the dynamic of the relationships centered around Anna (Keri Russell) the smooth, sylph-like dancer who evidences a shine for artistic endeavor and the artfulness of restrained love. However, Anna is undone by the haphazard. It comes in the prodigious shape of earthy, sensual Pale (Adam Driver) who like a force-of-nature inflames subterranean passions and blasts her out of her staid romance with Burton (David Furr) and easy routine with gay roommate Larry (Brandon Uranowitz).

After Anna’s one-time sizzling encounter with Pale, unbeknownst to Anna, her elaborately constructed inner psychic protections are shaken to their foundation. Her external “cool” and artistic resolve are broken wide open with the affirmation of life’s most chaotic of emotions which irrevocably will spin her into a relationship with the amazing and sensitive Pale.

At the opening of the play, Larry and Burton reveal their need for the friendship and the attention of the grace-filled and gorgeous dancer, whose nurturing kindnesses and moderate emotional tenor roll up and around marketing whiz Larry, and successful, screenwriter Burton. Anna receives comfort from both men in this expositional scene as they console each other about the loss of Larry’s and Anna’s other roommate, Robbie to an unfortunate accident.

(L to R): David Furr, Keri Russell, Brandon Uranowitz in Lanford Wilson’s ‘Burn This,’ directed by Michael Mayer (Matthew Murphy)