Category Archives: Broadway

‘Stereophonic,’ Adjmi’s Hit Transfers to Broadway

When Stereophonic opened at Playwright’s Horizons in the fall of 2023, the hybrid comedy/drama/musical was extended a number of times for a multitude of reasons. The acting was superb. The subject matter intrigued. Who is not enthralled by a smooth rock band on the cusp of greatness with a chonky financial contract, “getting their s%$t together,” as a small privileged audience watches them record their artistry in two sound studios? Under pressure, the two couple’s relationships straining, the husband-wife partners display pustules bursting with emotionalism, and the audience sees the interior of these relationships. What’s not to love?

This is live theater at its best. The audience lives moment to moment with the musicians (we have forgotten they are actors), riding to the mountain tops and canyons as we joy to their pain of creation, producing what may be a #1 album that soars to the top of the charts. In its transfer and Broadway premiere at the Golden Theatre, the cast, music, verité style, and arc of development are the same as is the three-hour length as in the original production at Primary Stages. Bravo. It is still a must-see.

Why would playwright David Adjmi (The Evildoers, Stunning), Will Butler, who wrote the terrific original music and lyrics, and superb director Daniel Aukin muck with success? The solid, winning substance of Stereophonic is about the five-member rock band and studio engineers working at an accelerated pace to record an album at two California sound studios in the mid-1970s. We get the “low-down” perspective of what it takes to be great.

Above all Stereophonic Broadway remains a stylistic masterpiece of theater verité with a view into two separate worlds, music creation and technical engineering, without which musicianship would not exist. The meld of the two in a great album reveals the dynamic genius of technicians and musicians, though the musicians are the public face who receive all the glory.

Two points to make about the production, which is integrated and fantastic from my perspective, with one suggestion. First, Stereophonic may not be understood by a “Broadway” type audience, who might not have the patience to work through the incredible detail of “moment to moment” dialogue and complications so organically constructed, intimate and authentic, that the realistic action brings one into oneself, rather than encouraging escapism in a flight of song and dance numbers characteristic of “the Broadway show.” In its brilliance, Stereophonic may not be fully appreciated for what it is. Stereophonic is a “one-of-a-kind” original that provides an electrifying evening of music creation as one would imagine happened in iconic recording studios like Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in Alabama or Abbey Road in London, perhaps, without the histrionics.

Secondly, in its staging at the Golden Theatre, a larger venue, the sound design has to be properly figured out by the designers, and the actors. They are not in a smaller venue. The actors must project, especially when their backs are turned from the audience. The sound design must be at equal level in every portion of the theater to eliminate dead spots. In the transitioning this must continue to be fine tuned.

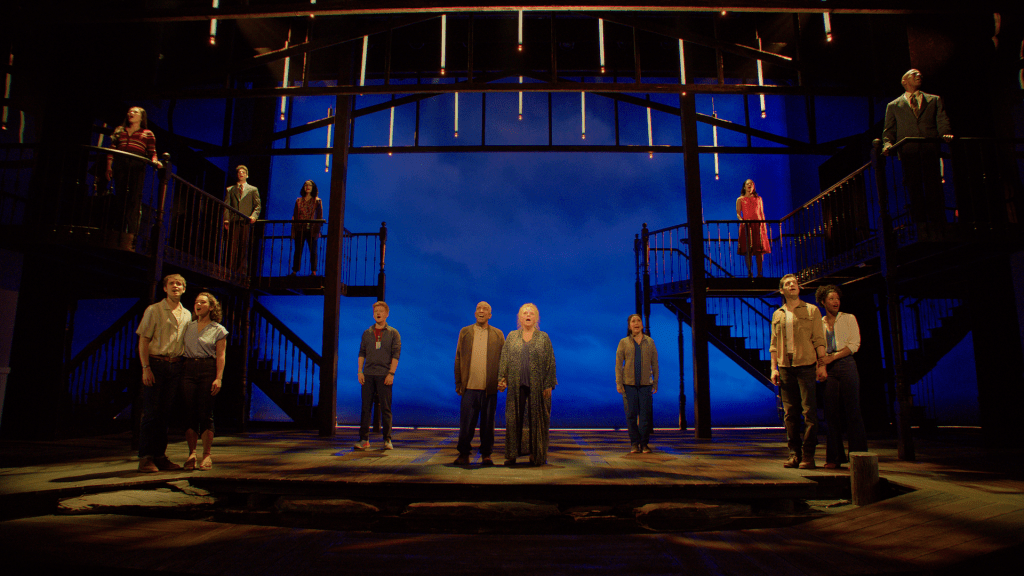

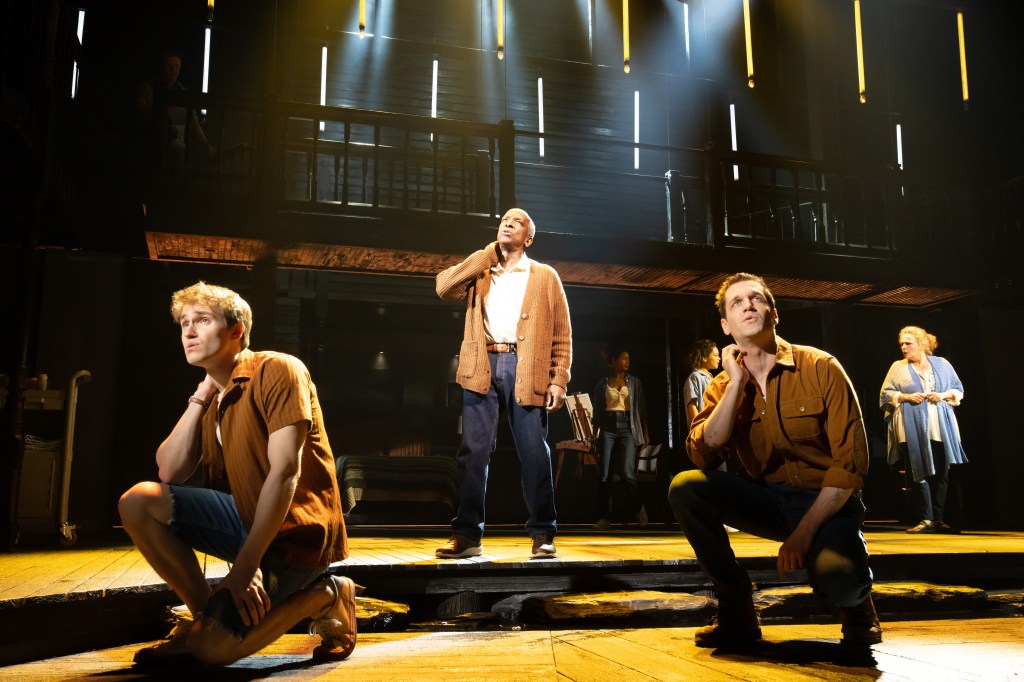

For rock fans and those fascinated by the ethereal nature of how bands collaborate, the Broadway production mesmerizes because we clearly understand the division between the musicians’ mystical artistry, which is always front and center, and the unseen, faceless, backstage engineering by Grover (Eli Gelb), and Charlie (Andrew R. Butler), who are finally revealed in process. It is the engineers’ artful techniques which enhance the overall effect and impact of each recorded song. This division of the two different realms of making music is beautifully manifested in David Zinn’s wood paneled scenic design, and Jiyoun Chang’s lighting design, which Aukin carried over to Broadway, along with Enver Chakartash’s period costume design. Robert Pickens & Katie Gell’s hair and wig design are new in this production.

As at Primary Stages, the Golden Theatre’s stage is divided into two sections. The upper level reveals the sound studio protected by glass, where we see and hear the musicians perform in a theater verité style, as they stop to revise tempos, add pauses, evolve riffs, etc. Downstage is the massive control panel where the engineers sit mostly with their backs to the audience and work to serve, manipulate, and stoke the musicians’ extraordinary talent and heightened emotional states, all the while discussing “their truth” with each other. With Aukin’s superior staging, we can track both worlds, feeling we are in their midst, interactively participating in music creation and understanding how the worlds precariously interact.

Though band members treat Grover and especially the shy Charlie as invisibles they don’t speak to, without their efforts the band’s unique identity and glorious sound wouldn’t exist. Therefore, in the production’s arc of development, Adjmi gradually uncovers the engineers’ centrality to the creative process and the band’s success. It is especially funny and poignant to witness how the engineers moderate the emotional infantilism of the “high-strung” musicians to get the recordings in top shape.

Throughout, drugs and alcohol become a panacea to quell the rough edges of sleep deprivation and stimulate a frenzied work environment. The cocaine, supplied by overworked engineers, keeps the band working at a frenetic pace. Ironically, drug use intensifies the arguments but floods the band’s creative juices.

Aukin’s vision of Adjmi’s themes of art, music, sacrifice and suffering, heighten the importance of sound engineers. They must have skill and expertise in the control room, as well as the personalities to cope with and manipulate artistic personas like druggy Reg (the hysterical and funny Will Brill), and diva Diana (Sarah Pidgeon).

For example Grover and Charlie must be temperate as Diana strains to get the notes, emotionally loses it, and must be encouraged by her partner lead musician and producer Peter (Tom Pecinka), to try again and again to “get it right.” Additionally, the engineers must be purposed to withstand the emotional word bludgeons from their “boss,” Peter, who launches off into a demeaning tirade against Grover and fires him. It is an idiotic move because Grover is the backbone of the album and Peter knows it. That is why he later makes Grover co-producer and apologizes.

The songs of Will Butler, (Oscar-nominated and former member of the Grammy-winning indie rock band Arcade Fire), remain as striking as ever. Indeed, one would wish that this band does produce an album, finishing the partial songs (we only hear a few in their entirety), that we hear them rehearse. The songs resonate with the themes of emotional yearning and the deceptions of fame, money and commercialism, the masquerade that they must avoid. If they embrace the commercialism, they will lose their way as artists, attempting to achieve perfection, a goal of the hard driving Peter.

Butler’s songs importantly reveal the raw emotions of anger and hurt, stirred by betrayal and loss that couples Reg (Will Brill) and Holly (Juliana Canfield), and Peter and Diana, experience in their relationships. Working frenetically together in close quarters to exceed the results of their previous album require sacrifice to be great. Peter constantly pushes them toward this. But by the conclusion as their work is finished, all have suffered for it. Simon (Chris Stack), who has been away from his wife and children for six months faces the threat of divorce and losing his family.

However, only Diana has been signed on to be a solo artist. Is the pain, suffering and sacrifice worth it for the others? Juliana Canfield’s Holly, a close friend and ally of Diana, congratulates her on this success. But we are left wondering if they will remain close or if the band will remain together to collaborate again?

A tour de force, Stereophonic runs over three hours with one intermission. Thanks to Adjmi, director Daniel Aukin, the sensational cast, whose acting chops and vocal talents are non-pareil, and the technical design team, the compelling forward momentum of the band’s creative dynamic resonates with powerful immediacy.

Special kudos goes to Music Director Justin Craig and Will Butler and Justin Craig’s orchestrations.

Stereophonic runs through July 7 at the Golden Theatre (252 West 45th Street, between Broadway and Eighth Avenue). www.stereophonicplay.com

‘Lempicka,’ The Art of Survival With a Paintbrush

Loosely inspired by tumultuous events in the life of Tamara de Lempicka, which gave rise to her provocative oil paintings of high society portraits and nudes in an Art Deco style, the musical Lempicka magnifies the theme of femininity unbound. The “unbound female” is a marvelous theme, perhaps annoying to some male critics, but welcome to most women, who have been undervalued and diminished throughout history. The expressive, glamorous and impassioned Eden Espinosa stars in the titular role. The premiere currently runs at the Longacre Theatre until September.

With the book, lyrics and original concept by Carson Kreitzer, and book and music by Matt Gould, this sensational, must-see musical is directed by Rachel Chavkin, who shepherds a superb creative team. The director effectively stages the action with her signature, fast-paced forward momentum. Minimalist, geometrically shaped scenic design elements and stylized ironwork scaffolding (Riccardo Hernandez’s design), adapt to the various settings. Thanks to the effective use of light and color (Bradley King), sound (Peter Hylenski, Justin Stasiw), and Peter Nigrini’s projections, the combining elements symbolize the cultural and historical references to the musical’s settings in Russia, France, and the United States.

Choreographed by Raja Feather Kelly, the amazing music is arranged and supervised by Remy Kurs. Lempicka reveals an incredible female artist, whose works Madonna and Barbra Streisand have purchased.

Chronicling the artist’s journey in flashback, Lempicka opens with a musical pop flourish to reveal an elderly woman sitting on a bench, “painting” en plein air, sans paints and canvas. Under the wide brimmed hat, Lempicka (“Unseen”), reminisces about her former glorious European life. Now, an “old woman that doesn’t give a damn; that history has passed her by,” she asks, “How did I end up here?”

The question is readily answered. She sheds her “old lady digs,” (Paloma Young’s costume design), and steps back into the past, transformed into a lovely, young woman, in a shining white wedding dress. It is the happy day of her marriage to wealthy Russian aristocrat, Tadeusz Lempicki (golden voiced Andrew Samonsky).

In a flurry of action in the next scenes, with jarring lighting, sound and bellicose revolutionaries, the Russian Revolution storms onstage (“Our Time”). Officials arrest Tadeusz, boasting that now everyone is like everyone else. Kreitzer and Gould’s book reveals Lempicka’s steadiness and presence in the moment, as she uses jewels and her body to save Tadeusz and baby Kizette. (The older Kizette is played by Zoe Glick.)

Within her heart and soul, Lempicka, a survivor with flexibility “in season and out,” converts the violence, oppression, and trauma of losing everything, into the building blocks of a unique artistic expression. After the family arrives in Paris as destitute refugees, with Tadeusz useless and despondent, she forces herself to paint for their subsistence.

Clearly, her experiences shape her art, and Chavkin’s vision, beautifully executed by her creative team, subtly ties the two together. Lempicka infuses her work with hints of her sexually frenetic lifestyle during the Anneés Folles in Paris, through the depression to 1939. Guided by her futurist teacher Marinetti (the superb George Abud), the art instructor insists “we are sober broken creatures; we need art that speaks to us now” in “the age of the machine” (“Plan and Design,” “Perfection”). Striking out in her own direction, employing some of his suggestions, Lempicka creates exquisite, tonal melds of steely, cool sensuality to convey her “larger-than-life,” shimmering, women subjects.

As her prime muse, she paints her lover Rafaela, the phenomenal Amber Iman, whose thrilling voice is sultry and seductive (“Don’t Bet Your Heart,” “The Most Beautiful Bracelet,” “Stay”). Despite Rafaela’s intentions “never to love,” they couple in an intense relationship that spurs Lempicka’s creativity to expand her chic brand. Rafaela helps her to forever solidify her iconic, ravishing, sensually bold artistry of women nudes and portraiture.

Her subjects bridged the worlds of Café Society and the underbelly of Paris’ open sexuality, represented by the Club Monocle, owned by audacious, bon vivant, Suzy Solidor (Natalie Joy Johnson). There, forbidden love and entanglements are encouraged because payoffs to the authorities allow such entertainment to flourish (“Women”).

In the opening scene’s moment of reflection, Lempicka says she, “loved more than life itself,” and specifically loved two people at the same time. They are Tadeusz and Rafaela. In an exceptional moment, they meet at Lempicka’s exhibition and sing “What She Sees.” Iman and Samonsky sing the ballad with gorgeous, resonating power.

As the Black Shirts, joined by Marinetti, flood the forbidden cultural spaces of Paris with intimidation (“Here it Comes,” “Speed”), they destroy Suzy’s club. The center does not hold, and Paris begins its transition to fascism’s conservative allure banning “decadence.” Lempicka’s life in Paris disintegrates. The operatic powerhouse number, “Speed,” is particularly striking as Tamara, Rafaela, Marinetti, Tadeusz emotionally convey the upheaval in their lives. Circumstances force them to rapidly spiral away from each other.

In a vital scene, Beth Leavel’s Baroness asks Lempicka to paint her for her husband’s remembrance. She is dying of cancer and encourages Lempicka to be with the Baron (Nathaniel Stampley), who is also her agent and an art collector. The way will be clear for Lempicka, divorced from Tadeusz at his insistence, because he can’t abide by her alternate lifestyle.

In “Just This Way,” Leavel’s pitch-perfect, full-throttled power brings down the house. Though the part is small, Leavel makes it loom gloriously. In the Baroness’s dying is the intensity of her desire to live forever in Lempicka’s incredible art.

When Lempicka and the Baron presciently flee Paris in 1939 ahead of the Nazi occupation, Lempicka forever leaves the philosophy, culture and wild personas that engendered her most appealing works. She settles into oblivion in Hollywood, as the flashback of her European life closes. At the conclusion, she sits “In the Blasted California Sun,” haunted by memories of Rafaela, who disappears, but like all those from her past, lives on in Lempicka’s artistry (“Finale”). Today, Lempicka’s paintings are worth millions.

Lempicka. Two hours, thirty minutes with one intermission. Longacre Theatre, 220 West 48th Street between Broadway and 8th Avenue. https://lempickamusical.com/

‘The Who’s Tommy,’ a Nod to the Past, and Segue into the Future

If you are a fan, The Who’s Tommy, currently in its first revival by Des McAnuff, (he directed the show’s original Broadway presentation over thirty years ago), may absolutely thrill you with its exuberant, pulsating electricity and phenomenal musical arrangements. With music and lyrics by Pete Townshend, additional music by John Entwistle and Sonny Boy Williamson II, and Ron Melrose’s music supervision and additional arrangements, it’s a gobsmacking explosion from the past for Boomers, and a scintillating acceleration into the future for Generations X, Y and Z. The production’s hyper-effects leave the music thrumming in one’s mind long after you leave the Nederlander Theatre, where the revival is currently in an unlimited run.

The rock opera which exploded on the music scene in 1969, in long album form was codified as groundbreaking, and eventually was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. Townshend’s chords and story line were memorized by legions in the immediate years after, as critics and fans alike interpreted what the story could be about.

Meanings and symbols spanned from Jesus to Buddha to Townshend’s own avowed inspiration, Meher Baba. The interpretation encompassed a spiritual leader who arcs the soul’s journey and helps mankind and womankind shatter the ego/carnal self to see and feel the spiritual immortality in their humanity. However, mistakenly assuming that everyone’s path toward wholeness can be achieved via the leader’s methods, he makes his followers do exactly as he did, making them suffer. His followers rebel and ultimately reject and metaphorically crucify the one they formerly idolized. The reward is not worth the path of suffering, denial and dedication to get there, they feel, as they take out their suffering on Tommy’s parents while he escapes to solitude and the seeker’s path at the conclusion.

Of course, these interpretations reflected the progressive spirituality and dedicated movement toward liberation of the late 1960s-70s, heavily influenced by psychedelics, flower power, gurus and shamans from various cultures, belief in peace-not war, and the Jesus Freaks movement (not the same as carnal, conservative evangelical, political Christianity today). Duly inspired, the maverick British film director Ken Russell created his hybrid fantasy drama musical based on The Who’s titular album. With an exceptional cast (Oliver Reed, Ann Margaret, Roger Daltrey, Tina Turner, Elton John, Jack Nicholson), Russell maintained the story which centered around traumatized Tommy Walker (Roger Daltry in the film). The literal story follows from the film and subsequent productions, Broadway (1993), through the first section until the latter part of Act II.

This latest Broadway revival veers off after the healed Tommy establishes his fan base and seeks to “correct” them with his methods. Townshend and McAnuff’s book sterilizes the retributive, shocking ending. Tommy purists may not like how the book truncates the force of the last half. “Tommy’s Holiday Camp” is cut, as is the subsequent brutality visited on his fans and parents. Some songs are added, without the same musical strength as those in the original album. The spiritual concepts are also minimized. Instead, this version emphasizes the visual, futuristic design spectacle of the production by David Korins (scenic design), Amanda Zieve (lighting design), Saragina Bush (costume design), Peter Nigrini (projection design).

It suggests video gaming culture and the small screen iPhones and Androids forever before our faces. In the suspended lighted frames of all sizes in various scenes that generally frame the story, is the theme that society and parents frame us. These frames echo and the central mirror framed by lights that Tommy repeatedly looks into and looks out of. The effect echoes the culture’s “branding,” boxing in everyone to fit in to get along.

Not having seen other productions, or The Who in concert, the updated, futuristic spin for me, carried its own message, themes and warnings. Certainly, with its high-tech projections and minimalist frame lighting, echoing the frame of the mirror which Tommy is obsessed with and his mother eventually shatters, we are reminded of our current culture’s preoccupation with gaming, selfies, ego, self-importance and encouraged selfishness. Especially through the staging and design, this version emphasizes such nihilistic obsessions and the danger of small screens whose App platforms brainwash, distract and seduce.

This theme moves throughout this revival’s technical aspects which align with our own culture’s deluded “deaf, dumbness and blindness” and the near cultism inspired by hand-held devices. These have increasingly disassociated us from our own natural environments and directed us toward a dystopian, fabricated world view of division, hatred and insult or complete distraction and entertainment with the effect of protecting adherents in their own information silos. This parallels how Tommy protects himself with his psychosomatic illness.

This version begins with Peter Nigrini’s fine production design that spins a black and white collage backdrop of the setting for 1941. Against that backdrop acted out are the Walker’s marriage, the German POW Camp, etc., as the Overture plays and the company sings.

Mrs. Walker (the sweet voiced Alison Luff whose climactic moment of shattering the mirror is delivered forcefully), gives birth (“It’s a Boy”) after which Tommy’s father, Captain Walker (Adam Jacobs), is believed to have died, though the war has been won (“We’ve Won”). Understandably, Mrs. Walker takes another lover (“Twenty-One”), but when Captain Walker returns to see his wife in the lover’s arms, he kills him in front of four-year-old Tommy (Cecilia Ann Popp and Olive Ross-Kline alternate days). Told by his parents to suppress what he sees and hears about the manslaughter, Tommy turns himself “deaf, dumb and blind” in a crazed psychosomatic obedience and rebellion against his warped, fearful parents (“Amazing Journey”).

As Tommy grows up unresponsive and uncommunicative with his parents and his environment (Quinten Kusheba and Reese Levine portray the 10-year-old Tommy alternating days), he is further traumatized by his pedophile Uncle Ernie (John Ambrosino’s part is sanitized in the song “Fiddle About”), and sadistic cousin Kevin played by the superbly arrogant, wickedly sinister Bobby Conte, who gloriously sings as the perfect, cruel foil to Tommy’s innocent. Both villains “babysit” Tommy as his parents neglect him (“Do You Think It’s Alright?”).

The actors portraying the younger Tommy are incredible as automatons. Their performances represent the result of horrid parenting and enforced objectification, when children receive orders then respond/rebel in original ways. In the story Tommy is an objects to be played upon and pushed around. I found this interpretation by McAnuff frighteningly symbolic, giving new meaning to parental abuse, neglect and force-feeding an obedient image, “acceptable” to his parents. They remain obtusely unaware about their integral part in suppressing Tommy and fashioning him into a non-person who screams “See me, Feel Me,” for he wishes to be free from the soul bondage.

Tommy’s future, older self is portrayed by the stellar Ali Louis Bourzgui, whose voice shatters consciousness itself with its phenomenal power and nuance. McAnuff has him stand in the light-framed mirror, reflecting back his alter-ego when the younger Tommys look in the mirror, their backs to the audience. This is open to interpretation. One possibility is a metaphoric representation of hope of who Tommy can become, including the whole person, free and in touch with his spirituality.

Though Tommy diminished three of his senses to suit his parents’ wishes, he compensates with an enhanced sense of touch and his sixth sense tied to his imagination (“Sensation”). A series of fateful events leads Tommy to become a pinball champion with his energized sense of touch. But despite this compensation and rise to fame, his parents want him to check in with reality, tired of the robot they created unaware. This leads to a series of interventions at a clinic and at a place where Tommy can receive drugs from the Acid Queen (Christina Sajous).

This wild scene in what looks like a crack den out of a Spike Lee Joint (film), reveals Sajous to be a desperate addict doing the bidding of her pimps. Jacobs’ Walker relents at the last minute and leaves with Tommy. It is another veering off of the original album and Russell’s film (with Tina Turner as the Acid Queen in an unforgettable performance in the film). This redirection which purists will object to de-glamorizes the positive effects of psychedelics in what is now becoming treatment for PTSD survivors and those with severe depression. However, sanitizing the Acid Queen scene also emphasizes the father’s desperation to have his son cured. He’ll try anything, but then realizes “anything” has its own potential horrors.

Obviously, Townshend and McAnuff keep the audience away from the disturbing and unsettling as much as possible, reflecting the conservatism of our times which ironically has given rise to the runaway chemicals of the pharmaceutical industry, controlled substances and highly addictive prescription medications like oxycontin and fentanyl. Both highly addictive “meds” have caused thousands more deaths than “orange sunshine.”

“Pinball Wizard,” the spectacular number sporting contrasting colors, flashing lights, searing projections and uber-technicals, as the grown Tommy “shows his stuff,” is breathtaking. Sung by Bobby Conte and the ensemble (with a nod to Elton John in the film by an unnamed “Local Lad” who belts out the opening salvos of the song and is fantastic), the audience experiences a gyration of emotions as the first act ends. The music has elevated and mesmerized, and one is left anticipating Act II with the timeless rock music pulsating through minds, hearts and bodies.

The first Des McAnuff production of The Who’s Tommy in 1993 starred Michael Cerveris as Tommy. The production, nominated for 11 Tonys, won five, including Best Original Score for The Who co-founder and musician Pete Townshend. The revival will surely be nominated, principally for its phenomenal find in the latest Tommy, Ali Louis Bourzgui, whose penetrating voice, compelling presence and powerful mien establish Tommy in all aspects of the character, implying sensitivity, charisma, spirituality and the ability to mesmerize and lead.

However, in updating The Who’s Tommy to make it relevant for our time, the spirituality and wisdom of the album’s meaning is inevitably softened to encourage a frightening look at our contemporary culture, albeit also softened. If anything is at fault with this version, though there is too much that is great which does mitigate any faults, a flaw is this. McAnuff didn’t go far enough with his vision to expose the importance of Tommy’s message-the need to return to spirituality, with direct references to the current ubiquitous technology, fake, hollow Christianity, and memes that seek to globalize, pasteurize and with cacophonous, information overload, overwhelm the importance of original unique voices emerging from the human spirit.

The finale attempts to do this. It happens as the audience and cast, who stands on the edge of the proscenium, sings “See Me, Feel Me”/”Listening to You.” It is enough, yes, but it also isn’t. With so much at stake in our present culture, with so great a need for people to return to inner healing and spiritual wisdom, McAnuff’s softening of the inherent villainy and spiritual revelations of the original album with an incomplete update of the cultural relevance, might be a lost opportunity. Regardless, I loved The Who’s Tommy.

Kudos to those not mentioned before. These include Lorin Latarro (choreography), Steve Margoshes (orchestrations), Charles G. Lapointe (wig & hair design).

The Who’s Tommy. Nederlander Theatre, 208 W. 41st. St., New York with one intermission. TommyTheMusical.com

‘Water for Elephants’ a Sensational, Poignant, Uplifting Spectacle

Based on the titular novel by Sara Gruen, Water for Elephants, excitingly directed by Jessica Stone, currently runs at the Imperial Theatre until September 8th. The production is a circus musical about redemption, love, courage and faith. With a book by Rick Elice and songs with a variety of dynamic musical styles and empowering lyrics by Pigpen Theatre Co., this is one of the finest, most rousing musicals to land its premiere on Broadway.

Water for Elephants richly incorporates the spectacle of the circus with stylistic artistry and well choreographed, impressionistic, acrobatic, aerial beauty. The company particularly embodies the spiritual essence of the beloved animals that are integral to the acts that barely keep solvent the foundering Benzini Brothers Circus, taken over by ringmaster/owner August (the excellent Paul Alexander Nolan).

However, before the spectacle begins, at the top of the musical, a wizened, grey-haired, tall gentleman, Mr. Jankowski (the fine Gregg Edelman), appears. He is serenaded by ghosts of the past (Prologue) which remain obscure in our understanding until Charlie (Paul Alexander Nolan doubles in two roles), returns Mr. Jankowski to the present from his reverie, and Jankowski good naturedly comments that he enjoyed O’Brien’s One-Ring Circus. As June (Isabelle McCalla) and Charlie make sure everyone is packing up, a few turns of dialogue later, the elder gentleman comments that June’s horse could use “a stress test.”

Immediately, we realize that Jankowski’s knowledge is particular. And when he says he is there alone because his kids were too busy to come with him, and he’s escaped from the “home” and that will put the nurses in a tizzy, we are intrigued by what deep element in his psyche has brought him to this small circus. Affable and pleasant, Jankowski ingratiates himself with Charlie and June. Warmed up by his inside knowledge of circus jokes, Charlie says Jankowski can use his phone to call a cab to return him to the “home.” In the interim, June offers to show him around as they discuss his involvement in the circus of yesteryear and the differences between then and the present-day. Finally, Jankowski, a former animal vet, offers to look at the mare that “needs a stress test.”

From this segue, the arc of development begins and Edelman’s Jankowski genially and intelligently narrates his involvement with the circus. As we move into the flashback, Edelman deftly walks us into the past. It is during the depression and Grant Gustin portrays Jacob Jankowski as a young man. In an amorphous scene of memory and voices, the older man sees his younger self reacting to the news of his parent’s death in a car accident, after which he was orphaned and left homeless. The powerfully voiced Gustin’s Jacob lives hand to mouth fending for himself. Hoping things will be better somewhere else, his destitution places him with other hobos on a train going wherever the wind blows them, (“Anywhere/Another Train”).

Jacob’s fellow riders Camel (Stan Brown) and Wade (Wade McCollum) are ready to throw him off this special train, but Jacob roundly stands up to Wade’s bullying aggression. Afterward, the two men who are roustabouts tell Jacob he hopped on a circus train and he can ride with them to the next town and stay for a day by making himself useful. There is fierce competition for every job, and he needs to distinguish himself to stay around permanently.

The stylized sets by Takeshi Kata in this scene of fast pacing movement are scaffolds on rollers which suggest a moving train with the help of the company, who create the bouncing motion which suits the rhythms of the music. Camel, who empathizes with Jacob, is the one who persuades Wade to allow him to stay for one day. Since Jacob elects to work with the menagerie, Camel tells him after they arrive in Utica and start setting up, he can earn his day’s keep by shoveling “s%$t.”

Director Jessica Stone and her creative team, which includes Shana Carroll’s circus design, Jesse Robb & Shana Carroll’s choreography with Mary-Mitchell Campbell & Benedict Braxton-Smith’s music supervision and arrangements, reimagine the interior, backstage world of the circus, of roustabouts, and the odd mix of personnel attracted to the nomadic, unique, showmanship of circus performance. In the musically synchronized “The Road Don’t Make You Young,” Jacob tours the circus and sees the insider’s scoop. The company of singers and acrobats swing mallets to stake the ropes for the Big Top and do daring twists and thrusts high into the air to commit muscular feats that take one’s breath away and rival the masters of Cirque du Soleil.

Jacob is nonplussed, figuring he will only stay one night, but is amazed to meet Agnes the Orangutan (Alexandra Gaelle Royer cutely re-imagines the reputedly smartest ape). Introduced to Barbara (Sara Gettelfinger), the mothering lead dancer of the “cooch tent,” Barbara tells him to get some grub and act as bouncer. Wade (August’s deadly right arm), renames her act to “Barbara and the Bally Broads,” and elevates them from the side show to the Big Tent to do “less strippen and more dippen.” Gettelfinger in a minor part plays it to the hilt.

As the song continues, Jacob, nicknamed Jake, also meets knife thrower and clown Walter (the humorous Joe De Paul), and Queenie his dog (a fluffy, long haired, hand puppet skillfully authenticated as a pooch by whomever “handles” her). By this juncture, Jake has met all those, who have been worn out by traveling the adventurous, road except the puppet master who keeps all in line. To conclude “The Road Don’t Make You Young,” owner August Rachinger presents himself center stage as the Broadway audience goes back in time to become the Benzini Brothers audience. In typical one-up-man ship razzle dazzle, Nolan’s ringmaster sings, “You wanna see something to set your spine tingling, something that blows Ringling out of the Ring?”

We question. Is he for real or just another blowhard exaggerating that chaff (the empty hull of a grain of wheat) is the meaty kernel of substance as he pretends his circus is finer than Ringling Brothers?

Unlike the quaint audience of the 1930s, who could not fathom black holes in space, television, quantum physics, cell phones, space stations orbiting the earth, Social Media and AI, we are the audience who experiences daily scientific wonders. What we’ve seen thus far on stage makes us understand August’s drive to be great in a time frame that is 90 years in the past before the dropping of the atom bomb. Additionally, we must consider that the parochial audiences of that time may rarely have seen a live lion.

Our disbelief at August’s pronouncement is gradually suspended when the action moves back to the present with the elderly Jankowski. Charlie and June act amazed when he tells him that this circus was the famous Benzini Brothers of 1931. The crux of the story, how the foundering Benzini Brothers becomes THE Benzini Brothers of 1931, an outfit which made circus history, but not in a good way, is the substance of Jankowski’s tale.

The turning point for the circus and Jankowski’s narration begins at the encouragement of June and Charlie in the present. They want to know what happened. It is then Elice’s book returns us to the past, when Jake hears the limpid voice of Marlena (Isabelle McCalla also doubles as June). She coaxes and attempts to calm the ailing Silver Star (the horse she rides who brings in the crowds), out of his pain by singing, “Easy.”

This is an exceptionally moving number as Antoine Boissereau infuses the agony of the horse with liquid movement aerially, as the white drapery flows with choreographed simplicity to effect his spirit struggle to stay alive despite his pained flesh. Jake is emotionally moved by Silver Star’s pain and the soulfulness of Marlena’s healing song. However powerful Marlena’s love is, Silver Star needs weeks of rest and recuperation to return to the center ring. If he doesn’t heal he will be lame, a death sentence for a star horse. Jake, uses the knowledge he has learned at Cornell as a vet, and his father’s experience as a vet. He tells August, who Jake finds out is Marlena’s husband, that the situation is dire for Silver Star.

August has him mercifully kill Silver Star which is a dramatic moment created by the Boissereau’s artistry. By that point August realizes Jake’s value and offers him a job. Jake avers because he realizes the pressure and tension he will be under having fallen for Marlena and having to live under the watchful and sinister monitoring of August whose behavior, at times is cruel and bellicose. When the train arrives too late at Wilkes-Barr, Pennsylvania where they try to get a replacement horse, they discover only Rosie is left for them to buy. August purchases her, and then is told she is an elephant, and they discover a truth her caretaker shares after purchasing her. She is one of the dumbest creatures anyone has ever worked with.

Humorously, not only has Jake fallen for Marlena, he falls for Rosie, who appears first as a trunk, then as various parts of an elephant in a clever “keep the audience wondering” if she will ever appear as the whole package. Interestingly, there is a meld of time, of present and past so that the elder Jankowski and Jake and Marlena sing the praises of Rosie (“Ode to an Elephant”) in another of Jankowski’s reveries.

With transformative hope, Marlena and Jake work together with Rosie as August suggests, while he sinisterly comments that Jake will never have Marlena and in effect threatens him away from her. Nevertheless, Rosie, Marlena and Jake work to try to get Rosie to do tricks with Marlena. In these sequences with Rosie the past is the present. Mr. Jankowski relives the hard work they go through with Rosie, who just doesn’t get much of what they are trying to teach her. (“Just Our Luck”) (“I Shouldn’t Be Surprised”)

Meanwhile, if they can’t get Rosie in the center ring with Marlena as their main attraction, the circus which was foundering will completely fail. They need a miracle. Wisely, Stone teases the audience with what it wants to see, Rosie in full regalia as the beautiful elephant that all, including the company, have been singing about. Tantalized, we see the shadow of Rosie whole, but have to wait for her in fullness, until after the romance between Marlena and Jake blossoms in a kiss that happens almost unconsciously and whose “tell-tale” signs of lipstick alert Camel to warn Jake that he won’t be able to handle the trouble August will bring upon him for stealing the affections of his wife. Likewise, Barbara warns Marlena off Jake. However, both cannot help themselves.

Despite Marlena not getting Rosie properly trained for her star performance, August pushes the issue because they are desperate for the money the act will bring. In “The Grand Spec” Nolan’s August and the company superbly whip up the crowd as we anticipate seeing Rosie do “her thing.” When he is left standing with no stars emerging, the humiliated August runs backstage and attacks Rosie and beats her, trying to get her to move. We hear her pained trumpeting cries, and then she defends herself and knocks down August. She is ready to stomp him when the miracle happens.

Jake in the twinkling of an eye reacts and Rosie stops herself from killing August whom she hates. The day is saved and the audience finally sees Rosie in full form. She is awesome in all her glorious, sensitive puppetry thanks to Caroline Kane, Paul Castree, Michael Mendez, Charles South and Sean Stack. “The Grand Spec” concludes and August finally becomes what he’s dreamed of being, the proud, successful “ringmaster extraordinaire.”

However, this achievement is at great cost, for he realizes he has harmed his relationship with his wife. Jake’s success with Rosie and August’s own cruelty and jealously have pushed Jake and Marlena together. She hugs Jake celebrating their success. Though she blows August a kiss, his inferiority and insecurity make him feel the loser. Nothing she can say and do will arrest his thoughts that Jake and his wife are lovers, though nothing but a kiss and hug has happened between them.

Thus, one problem is solved, however, unchecked psychologically, August, who should be thrilled with Rosie and Marlena’s sensational act, is driven toward distrust and anger. He drowns in his own bitterness that the reason why the act with Rosie is a success is because of, Jake, who has become invaluable.

Act II unfolds as the conflicts increase among August’s circus people and himself as well as August, Rosie, Marlena and Jake. In the first act we have a clue to August’s character (“The Lion Has Got No Teeth”); he feels he is a worthless fake. Though he glories in it and embraces his lies, this attitude does nothing to uplift him. August allows his envy of Jake, who is his superior in attitude, personality, education and kindness to animals, to be his undoing. Instead of realizing Jake and Marlena love each other and it’s time to move on, his cruelty and thuggery (we see how Wade, his lackey, acts out August’s evil wishes) cause him to seek vengeance. This spills out onto others in his company, and we note that he becomes so loathsome, that he cannot even stand himself.

Nolan is the perfect, nuanced villain that we can understand because Elice’s characterization gives the actor so much to work with. Likewise, with the other characters who are strongly portrayed in song i.e. (“I Choose the Ride”), a song which Camel leads beautifully, we understand the choices the characters make. These ultimately lead to their victimization by August who becomes more and more tyrannical and vengeful without good reason. How he moves against Walter and Camel is terrifying, and McCollum’s Wade haplessly allows himself to be ill-used and exploited by August.

Once more we are reminded that evil flourishes because potentially good people do nothing to stop it. In Wade’s instance, he services August’s wickedness for his own purposes, willingly becoming his slave.

The energy and enthusiasm of the acrobatic dancers of Act I are even greater in Act II. Importantly, their action arises organically from the sequence of events that occur. Nothing the creative team does seems extraneous or out of place in the circus world. And it is a delight to watch their expertise and phenomenal talents singing, dancing and doing exploits during the various musical numbers which range from jazz, country, blues, ballads and more. The score and complex lyrics by Pigpen Theatre Co. have been reworked, honed and refined to precision.

This is one to see for the outstanding performances, the acrobatics and aerial spectacle which are extraordinary. The circus design makes sense in Stone’s creation of a small-time circus of 1931, run by a flawed ringmaster who attempts to keep things together, despite his interior brokenness. The director’s staging capture’s the novel’s ethos and heightens all the characters’ vulnerabilities. August’s failings make him the perfect foil for cruelty and exploitation. His darkness is made all the more evident in contrast to Jake, who in every way is his opposite, especially in his humility, gentility and decency.

There is one scene taken out of Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables, which clues in the differences in the soul conflict and morality between August and Jake. Jake has the opportunity to kill August while the ringmaster sleeps. His goodness wins out and he stops himself. It’s a marvelous inclusion in an intricately woven, profound musical about individuals pressed by circumstances toward the abyss, until they free fall into their own inevitable demise.

Kudos to those not mentioned above which include David Israel Reynoso’s costume design, Bradley King’s lighting design, Walter Trarbach’s sound design, David Bengali’s projection design, Campbell Young Associates’ hair & wig design and Ray Wetmore & Jr. Goodman, Camille Labarre’s puppet design. Finally, the music was compelling thanks to Daryl Waters, Benedict Braxton-Smith, August Eriksmoen’s orchestrations, Music Director, Elizabeth Doran and Music Coordinator, Kristy Norter.

Water for Elephants. Imperial Theatre, 249 West 45th Street, between 7th and 8th. 2 hours forty minutes with one intermission until September 8th. https://www.waterforelephantsthemusical.com/

‘An Enemy of the People’ Brilliant, Drop Dead Tragicomedy With Jeremy Strong, Michael Imperioli

In Amy Herzog’s adaptation of Ibsen’s sardonic An Enemy of the People, currently at Circle in the Square for a limited engagement, we are treated to a modernized version of a work whose timeless verities ring true for us today. Aptly directed by Sam Gold (A Doll’s House Part 2), Jeremy Strong (TV: “Succession”) as Dr. Thomas Stockmann and, Michael Imperioli (TV: “White Lotus”) as his brother, Peter Stockmann, go head to head about a subject that should concern every politician and citizen on the planet: clean, potable water.

In adequately slimming down Ibsen’s five act play to highlight important themes that are taken out of our current headlines, Amy Herzog confirms her penchant for adaptation. Successful with the process of refining, to trim the salient dialogue and concepts of a classic work, Herzog’s minimalist adaptation of A Doll’s House was nominated for a Tony Award. Likewise for An Enemy of the People, Herzog tames the unwieldy Ibsen sentence construction and vocabulary (sometimes hampered by translation from the Norwegian), so its clarification provides accessible, trenchant, stark meaning with a greater impact than the work may have had in an original translation.

Other changes in characterization compact the play’s crystalline focus. Conjoining two characters (Petra and Mrs. Stockmann) into just daughter Petra (Victoria Pedretti), Herzog humanizes Dr. Stockmann, who misses his dead wife, and is gratified that his remaining family is close and supports him. Reinforcing Petra’s identification with her father, Herzog intensifies Stockmann’s dilemma and persecution which becomes Petra’s problem as well. So we appreciate her defense of her father and courage in braving the victimization and town’s retribution after the doctor attempts to save the town from itself by blowing the whistle about a nearby spa’s contaminated water supply.

Herzog emphasizes the situation and brings it rapidly to a crescendo. It begins with acknowledgement of Stockmann’s heroism by his friends. The fine scientist and researcher sends the nearby resort’s water sample to the university lab which affirms disease-causing, killing bacteria in the water. In Europe those who would visit spas for treatment, sometimes would “take the waters,” meaning drink the waters for their reputed, curative healing effects. Stockmann has discovered that if the patrons sip the “healing” waters, the tourists will become deathly ill. If they bathe in it, perhaps the polluted water won’t be as immediately disastrous, but it will be dangerous. This is Ibsen at his sardonic best and the message is meaningful for us today, (water damaged by PCBs, microplastics, hormone disruptive contaminants). Though Ibsen wrote the play over 140 years ago, little seems to have changed.

When Stockmann’s more liberal friends, newspaper editor Hovstad (Caleb Eberhardt), his assistant, Billing (Matthew August Jeffers), and even Aslaksen, Chair of the Property Owner’s Association and printer (Thomas Jay Ryan), hear of Stockmann’s prescient action, they deem him to be heroic in “saving” the town. During their discussion we find out that both Hovstad and Billing resent the wealthier investors having come from impoverished backgrounds; they encourage the doctor to publish the report. Additionally, Aslaksen, wants to hold a dinner party and present Stockmann with a small award. Aslaksen, a self-declared “man of moderation” says, “nothing too flashy, we don’t want to ruffle any feathers.

To complicate the situation, Stockmann’s father-in-law, Morten Kiil (David Patrick Kelly), who is still alive and a wealthy man, owned one of a number of tanneries near the spa area. Apparently, Kiil and the other tannery owners “forgot” to properly dispose of the chemical runoff used to cure the hides and the poisons have seeped into the water table. (Think of Jonathan Harr’s book and adapted film A Civil Action, about the pollution of the Woburn, Massachusetts water supply that sickened and killed children and families.).

Petra reminds her father that he suggested before the construction of the resort that they make adjustments for such a possibility because Stockmann feared the tannery’s proximity. However, his brother, Peter (the town mayor), the investors and officials shot down the doctor’s idea because of additional cost and delay. Their wants were understandable; the sooner they opened the resort and spa to make money and bring tourists in droves to the town, the better. Indeed, the town, in anticipation of the spa’s opening in the summer has grown more prosperous and the people are looking forward to servicing the tourist trade that the spa will bring.

Clearly, money “trumps” the viability and security of the spa. Stockmann’s science and the safety and sanctity of human life are in bondage to financials and commercialism. The developments that follow after Stockmann receives the lab report hang in the balance. Will his boss and brother, the mayor and investors agree that the situation warrants rehabilitation of the baths, though that might jeopardize the town’s commercial viability? Or will the mayor and investors hold the line that the spa and resort be opened and celebrated, despite the potential harm to come? In other words should the truth be exposed or covered up?

The brothers are on opposite sides of the dilemma; one represents science, the other the town’s economic prosperity. A critical factor is that Peter is Thomas’ boss and Thomas answers to him. As Dr. Stockmann lives for his work, so does his brother Peter, who has never married and demonstrates overweening pride as the mayor servicing the richest, most prosperous citizens. If they were at odds with each other before, with Peter ignoring his brother’s scientific suggestions and criticism of his “liberal” newspaper friends, their conflict explodes after the doctor confronts Peter with the report.

Unfortunately, the doctor’s idealism and self-righteousness has blinded him, as Peter’s greed, self-importance and his rich friends sway him beyond human decency. Peter appears to hold all the chips in this poker game. Their struggle is an iconic one and Gold’s direction and Strong and Imperioli’s acting are on-point superb during their interactions and arguments and especially at the town meeting.

Of the doctor’s three friends, Aslaksen is the one who anticipates that various townsfolk may not perceive Stockmann as a hero. And indeed, when the mayor reads Stockmann’s report, he takes it personally as an attack based on resentments stemming from their childhood. Beholden to wealthy interests, Peter actively dismisses the gravitas of what Thomas suggests and refers to his brother’s pronouncements as “speculation and wishful thinking,” and he insists the doctor’s attitude is “spiteful and childish” for cutting off the town’s “only” source of income.

From his perspective the proof screams at Thomas about how dire the situation is. Thus, the doctor expects his brother to retrofit the baths and delay the opening of the spa, though he has not researched the practicality of how long it will take and how much it will cost. The situation can be mitigated if the two sides agree to tackle the problem rationally and intelligently. However, both brothers cast it as an either or situation and Peter is predisposed to cover up the noxious, infernal truth and proceed with the spa’s poisoned-filled opening.

The genius of An Enemy of the People is the way in which the situation and character interactions reveal social and personal dilemmas. Do we uplift human rights supporting the sanctity of life and security for all as the doctor does? Or are rights subject to economic and class background and curtailed accordingly, as Peter wishes? Are we generous and life-supporting or selfish and nihilistic? Are those with money truly superior or is their arrogant, self-importance riddled with flaws because to value money and power over human life is suicidal folly that leads to catastrophic, karmic consequences?

In this play, Ibsen reveals the perniciousness of toadying to class and money at the expense of life and health. And so it goes with Peter, the mayor, who bows to special interests despite the apocalyptic moral imperative that the spa will kill instead of heal. According to the mayor, the cost and delay will bankrupt the town. He manipulates and threatens Thomas’ friends Hovstad, Billing and Aslaksen so that they turn against Thomas to “save” the town from the financial debacle that will occur if the spa closes.

As forces converge against Thomas, and his friends who once stood by him back away from his facts, we note that financial viability is the only consideration, when it doesn’t have to be. The arguments given settle in the “benefit” to the town’s prosperity which will be destroyed if they take two years to retrofit the spa. The spa supporters affirm that surrounding towns will jump in the gap and create their own resorts and wipe them out competitively by the time they finish their corrections. If they cover up the truth, at least the town will prosper commercially and the investors will receive an immediate return on the investments.

In their arguments, not one of the spa supporters, Stockmann’s friends or the mayor consider that tourist deaths and subsequent lawsuits could force the town into bankruptcy. Even worse, the scandal of a cover-up and eventual publicized expose will necessitate investigations and the public humiliation and outcry that such was allowed by the mayor, etc., destroy the town’s reputation and revenue for a long time to come. The gaslighting notion that the doctor’s facts are “speculation” is actually the fantasy (“wishful thinking”) that the bacteria and poisons in the water are not harmful and/or don’t exist. The investors, town and mayor are “damned if they do, and damned if they don’t.”

Rather than correct their attitude and behavior, Peter and his supporters double down on their initial dereliction in not following the doctor’s suggestions. They turn on him blaming him for the situation which they negligently in a criminal dereliction of duty refuse to believe and act on.

Strong’s doctor gives an impassioned speech to Peter, Hovstad, Aslaksen and Billing. He prophesies that he will present the truth at a general meeting and save lives regardless of their position not to publish the report. The town should be able to hear and decide the best path to take. At the end of his arguments with Aslaksen, his brother and the others he states, “I have faith in the people of this town. You can fire me, you can shun me. But you can’t stop me from telling the people the truth.” Strong’s performance is authentic; we believe him and hope with him. It is a superbly unforgettable dramatic moment.

It is also an excellent place to create “the pause” (not an intermission), which lasts five minutes, then segues into the town meeting where Stockmann presents the report. The playing area is converted from Dr. Stockmann’s atmospherically lit house and study, into a well-lighted bar where drinks (aquavitae) are served to the audience. Gold has dynamically staged this segment so that audience and actors mingle and imbibe for the five-minute interval. The atmospheric lighting of the first half of the production with gorgeous antique lamps from that period is replaced during this “pause”. The theater’s regular lighting is turned on as the drinks are served. It stays on, then, as the town meeting gets underway, and the play resumes with lights down, Dr. Stockmann confronts the mayor, his former friends and the townspeople.

This is genius staging because during the “pause,” Gold moves us from the past to the present in a time meld, and we are reminded of the currency of this play’s situation and themes.

Then the town meeting ensues. It is terrifying and fascinating. The mayor, Hovstad and others shut the doctor down with loud verbal muscling. When Thomas stands up to them speaking the truth, whipped up by the mayor and others, the townspeople repeat the others’ refrain that Thomas is “an enemy of the people,” and physically beat him. Strong’s performance and the ensemble’s counter-performances are incredible.

As we stand in the doctor’s shoes, we identify with his untenable situation which is beyond irony. This is especially so after he is pummeled with buckets of ice (the symbolic equivalent of a stoning) thrown on top of his head. Strong’s Stockmann rips off his shirt and offers his life for them if only they would accept the truth. The irony is complete. The townspeople and his brother want their fantasy. His life and their own lives are worth nothing. Money is everything. They believe that the spa will bring prosperity and money though they may not live to see it. They can’t handle Thomas’ “facts.”

We have seen this picture played out before in the COVID political botch job of the former president, who, like Peter the mayor, eradicated the deadliness of the virus with his lies and misdirection, as the US charts the largest number of COVID deaths globally to date; yes, people are still getting COVID and dying from it. The townspeople’s rejection of Stockmann’s facts hyped up by the mayor and his cohorts parallel MAGA’S convenient rejection of the truth for “alternate” facts (conspiracy theories) which they rabidly cling to in a morbidly cultish intractability whipped up by MAGA politicians. Then as now, science is rejected by those who wear their lack of education and ignorance on their sleeves, as the facts become others’ “wishful thinking.”

What is particularly ironic about seeing this production is the extended parallel of censorship then and now but differently processed. Ibsen never imagined media, social media and AI. Instead, of publishing Thomas’ factual report, the town paper is silent about the danger, censoring the report. Today, lies are broadcast on various media platforms including “Truth Social” precisely to extinguish the credibility of facts. The loudness and cacophony of wrong information and falsehoods deafen those willingly, lazily duped into a conspiracy of complacent trust. Those who would not be duped must read extensively to separate truth from lies and silence the cacophony to tease out what is really happening.

Do we laugh or cry? My response to Strong’s impassioned speeches after his beating and vilification was panic laughter and a few tears at the enormity of witnessing the play’s themes which resonated for me as an anti-MAGA who watched Republican truth-tellers like Liz Cheney, the former president’s Republican administration witnesses at the January 6th Commission, Dr. Fauci, former Governor Andrew Cuomo, and a legion of others who stood and still stand for the truth against the fraudulent former president. For their pleas of truth, they, like Strong’s Stockmann, have been symbolically crucified, character assassinated, demeaned, defamed and threatened with death. The dark ironies of this production are drop dead tragicomedy that is nonpareil in today’s theater.

And as such, this production is a warning. The message for me was “not on my watch!”

There are those who deny and punish truth tellers, whether scientists or Cassandras. Indeed, the more the leaders and their followers cry for blood, it would seem that the greater the confirmation that what is being said that inflames them is accurate. The final twist in this magnificent work which Herzog, Gold and the phenomenal actors have made as plain as day, you will have to see for yourself, if you can get a ticket. The conclusion just might involve a rescue by Captain Horster (Alan Trong), keen on Petra, who offers to take Stockmann, Petra and Stockmann’s son to America. Why? It is better there and the citizens are more amenable to hearing the truth. The audience laughter was as bitter as the dark irony inherent in Captain Horster’s innocent comment.

Re-imagining An Enemy of the People, Herzog, Gold and the creative team have delivered a searing, terrifying and at times humorous work that will remain in one’s consciousness long after one leaves the Circle in the Square. From the imaginatively stylized, technically galvanizing and evocative set design by dots, to the superbly thematic lighting design by Isabella Byrd, the period costume design by David Zinn, and Campbell Young Associates hair and wig design, the director’s vision coheres powerfully.

The singing of Norwegian folk ballads throughout is an additional atmospheric element that establishes setting and grounds us in history. Norway is a place that is often presented as more forward thinking than the US, another irony. Human nature is similar everywhere, especially when ignorance can be manipulated for profit and the illusion of prosperity for the poor, which rarely happens. Mikaal Sulaiman’s sound design helps to convey the timber of the music and voices. It might have been interesting to see a translation of their lyrics in the program.

An Enemy of the People is in a 16 week limited engagement that ends June 16. It is two hours with a five minute pause and no intermission. Circle in the Square, 235 West 50th St. between 7th and 8th. See it for its performances, the fine direction and inspired re-imagining. https://anenemyofthepeopleplay.com/

‘The Notebook,’ Poignant, Reverent, Knockout Performances by Maryann Plunkett and Dorian Harewood

Fans who have seen the film or read Nicholas Sparks’ titular novel will not be disappointed with The Notebook on Broadway, currently running at the Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre. With music and lyrics by Ingrid Michaelson and book by Bekah Brunstettter, the musical based on the Sparks’ novel dramatizes the relationship of Noah and Allie using different couples to represent their life stages. With a few changes in the setting from the novel, young and old can appreciate the deeply personal aesthetic and profound expression of fidelity, not often seen, that reveals Allie and Noah’s intimacy and devotion to each other.

Directed by Michael Greif & Schele Williams, The Notebook’s staging is fluid and stylized, happening mostly in remembrances past. It simultaneously layers the key turning points in the stages of Allie’s and Noah’s relationship (teenage years, late twenties). Through vignettes of scenes between the young Allie (Jordan Tyson) and Noah (John Cardoza) and then the middle Allie (Joy Woods) and Noah (Ryan Vasquez), we understand how the couple’s relationship developed.

We are kept in suspense when Allie’s parents disapprove of Noah and they don’t see each other for years, each pursuing their own dreams. We learn what stood in their way to break them up, and discover how they eventually get back together again, despite their differences in background economically and socially.

The musical takes place in the present in a nursing home where Old Noah (the superb Dorian Harewood), lives to stay near his wife Allie (an incredible Maryann Plunkett), who has degenerative Alzheimer’s. If you have not seen the film or read the novel, you are unaware of Noah’s identity and intentions until he meets with his family and they tell him he cannot afford to stay with their mom in the facility to keep her company. He has to let her go. However, their bond transcends even their children. Noah ignores them.

The strength of the musical is in Greif and Williams’ staging that suggests memory and consciousness brought to life by the journal that Noah reads daily to Allie in her room in the extended care facility. Allie wrote the memoir in remembrance of their love. Noah’s promise to read it to her was made, we learn, when she realized she was becoming immersed in the darkness and confusion of early onset Alzheimer’s. She desperately hoped her own words would trigger her consciousness and memory to maintain their powerful love connection.

The musical’s inherent focus on memory and the indeterminate nature of time in human consciousness reveals how love transcends, heals and can make memories as alive as reality. Eventually, the truth can break through, as it does by the conclusion of the musical, when Allie realizes who Noah is and why he is with her every day. If one has had experiences with relatives who have Alzheimer’s, some relate that in the midst of their relatives’ seeming insentience, there are moments of clarity that appear miraculous. How and why this occurs with this unfortunate condition remains a mystery which one day may be solved.

In respectful consideration of Allie’s situation, Brunstetter’s book encapsulates The Notebook from Noah’s perspective. The directors are mindful of how Noah’s memories and Allie’s words stir Allie, Noah and even Fin (Carson Stewart), who at one point picks up the journal and reads a steamy scene that humorously wows him.

Predominately, the directors strive for coherent, symbolic and meaningful interaction between the couples’ vignettes chronicling, not always in order, but thematically, the events expressing Noah and Allie’s eternal bond created before they were married. As Noah dozes in a chair and dreams of the formation of that bond between Young Noah and Young Allie, the actors are situated downstage to the edge of the proscenium, where there is water and a shoreline bathed in Ben Stanton’s beautiful, bluish tinged moonlight. The night scene conveys an atmosphere of romance. The brief dialogue indicates the couple’s youthful naivete and exuberance where anything is possible even their love. Tyson’s Allie says the words no lover wants to hear; she has to “go home” to her parents.

Ironically, these are words Older Allie in the present says to the nurses and to Old Noah, in confusion, as if she’s searching for the comfort she associates with the home she once made with her life’s partner standing before her, who she doesn’t recognize. Plunkett’s Allie, unsettled in the extended care facility, is triggered by a past that nudges just below her consciousness. She tries but fails to remember the house that Noah built just for her. If only she could get back there, she would know where she is in the present and who the old man is who comes to visit every day.

In that first moonlight and romance scene, Young Noah’s response of eternal love is that Young Allie can stay with him forever, to which she playfully agrees. Simplistic, facile teenagers make promises. However, it is the rare relationship and rare individuals who keep promises in a world of lies, canards, fakery, AI, betrayals, and deceit, where “forever” love is expressed to “get over” and treachery and selfishness are the game plan.

The Notebook is profound in its simplicity, and can be underestimated. Indeed, who is able to love forever, be faithful to one person forever, and not just give lip service to a relationship? This is a key theme of the musical, for through Noah’s unwavering fidelity and Allie’s words, we see how this is possible for this couple who loves simply and endearingly. Overall, the production manifests this theme with sincerity aided by the phenomenal performances of Plunkett and Harewood, who pivot the action forward as the Noahs and Allies affirm the beauty of the relationship in snippets of dialogue and the vitality of song.

Young Noah and Allie lightly reference a forever love which indeed comes true; both age together and Old Noah stays with Old Allie to the very end of their lives. Likewise, the promise they make as kids to see each other the next day also comes true in their lives together, even when a gulf of oblivion separates them. Old Noah sees Old Allie in her room to read from the journal in hope every day. Plunkett’s masterful effort in presenting Allie’s struggle to know her identity and Noah’s, paves the way for the payoff at the conclusion, where she remembers, and together they metaphorically return forever to the home they have made of their love.

The music and songs resonate, some more forcefully, some more lyrically than others. The opening song that Harewood’s Noah sings with the ensemble (except for Older Allie), “Time,” is an inspiring and soulful ballad that embraces life’s mutability and time’s swift passage. The song summarizes the permanence of their future relationship and unfolds with the presence of the younger and middle couples who sing with Old Noah symbolizing Allie and Noah’s younger selves.

It is a soundscape of memories where they identify how they live “to keep going, keep running, keep standing, keep leaning, keep learning, keep hoping.” This premiere ballad establishes what’s to follow, as the ensemble’s voices meld with loveliness in lyrical harmonies. This first song, the song at the end of Act I, “Home,” and the final song, “The Coda” are the most powerfully wrought and most memorable and significant in relating the love and devotion of this unique couple who have been blessed in their love and faithfulness.

Throughout Act I Old Noah persists coaxing Old Allie with the journal passages, and we follow the narrative of their first kiss and first intimacy, first fight, first pledge to write to each other. The musical reveals these two are drawn to love on another level, which is the mysterious unseen of love relationships.

This is in contrast to the socially acceptable diagram of “successful love and marriage,” which Allie’s mother (Andrea Burns), wants for her daughter. Allie’s mother defines happiness by the society’s values of career success and college education, which Allie is forced to accept because of her mother’s betrayal for “Allie’s own good.”

However, Allie and Noah’s relationship, unlike Allie’s mother and father’s relationship, is not defined by material things and upward social mobility. Though Brunsetter doesn’t mention “spiritual” vs. “material,” the undercurrents are clear when the excellent Joy Woods’ Middle Allie in her solo numbers affirms who she is and who she wants to be (“Leave the Light On,” “My Days”). To what extent Noah is a part of who she wants to be, she discovers when she returns to the town and is drawn by curiosity and an unconscious, perhaps spiritual desire to locate the house Noah has built and outfitted for her with his superb carpentry and woodworking skills.

In the subsequent scene the invisible bond between them manifests. We discover what prevented them from being together sooner in a powerful scene between Burns’ mother and Woods’ Middle Allie. Instead of belaboring additional details, Brunstetter moves the action to its foreshadowed conclusion. This doesn’t occur before a few suspenseful, gyrating events in flashback and in the present. One is that Old Noah, who is in the hospital after a stroke, won’t be able to keep his promise to rekindle Allie’s memory ever again.

Kudos to the creative team who carried the directors’ visions for The Notebook. These include David Zinn & Brett J. Banakis (scenic design), Paloma Young’s color coordinated costume costume design, Ben Stanton’s lighting design, Nevin Steinberg’s sound design (I could hear every word) and Mia Neal’s Hair & Wig Design. Additional kudos to Carmel Dean’s music supervision and arrangements and Katie Spelman’s choreography.

The Notebook is a must-see because of the performances and the directors’ vision in bringing reality to a popular work of fiction. Ignore the pandering “tear-jerker” comments by some critics for whom fidelity and eternal love may be empty promises.

The Notebook, one intermission runs until November 24th. Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre, 236 West 45th Street between 7th and 8th. https://notebookmusical.com/tickets/

.

‘Doubt: a Parable’ The Revival With Liev Schreiber and Amy Ryan is Exceptional

If nothing is certain but uncertainty, then “doubt” is a natural state, as genius quantum physicist Werner Heisenberg in his uncertainty principle postulated. However, in the realm of faith, “doubt” may be a blasphemy as scripture encourages Christian adherents to “walk by faith, not by sight,” believing fervently, blindly in God and His truths. Such is the position that Sister Aloysius Beauvier (Amy Ryan) initially presents in John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt: a Parable ably directed with specificity and edginess by Scott Ellis.

Doubt, currently in its first revival on Broadway since it premiered in 2005 continues to be a controversial powerhouse exposing embarrassing infelicities about the Catholic Church and the patriarchy.

In this beautifully acted revival running with no intermission at Todd Haimes Theatre, we note how the play emphasizes many of the divisive cultural issues at stake today though the setting is 1964, the Bronx, New York. However, Shanley nails the timeless sticky problems operating then and now with institutions that are incapable of policing themselves when they are run by men. Specifically, the play delves into church sponsored schools. Their male dominated hierarchy and paternalism shuffled off the harder tasks of teaching, learning and administration to the women. In this instance, the Sisters of Charity do the scut work in “collaboration” with the diocese in the fictional St. Nicholas Church.

To highlight his themes Shanley contrives a situation among three religious adherents who influence children toward or away from Catholic tenets. These include the charismatic Father Flynn (Liev Schreiber), pastor of St. Nicholas, the school principal, Sister Aloysius, and neophyte teacher and nunm Sister James (Zoe Kazan). Their dynamic interplay reveals age-old issues about the best and worst of human nature, goodness, egotism, arrogance, the need to control through guilt and fear, inability to discern lies from truth, gender inequality and hypocrisy.

Doubt opens with Schreiber’s Father Flynn addressing the audience as his congregation, preaching a sermon on the opportunities of having doubt as a part of the bonds of faith. Father Flynn’s sermon frames the play’s arc of development and the subject becomes the driving force as each character confronts their uncertainties about what is right, decent, truthful as they project their own inner weaknesses onto the behavior of each other. Importantly, their uncertainties reveal a crises of their faith in God to move them through the darkness. Instead of allowing God’s love to unify them, darkness, suspicion and doubt overcome them.

The second scene opens on the office finely outfitted by David Rockwell’s wood paneled set design on a turntable which later revolves to show a pleasant Garden and backdrop of the city beyond. Sister Aloysius unleashes her intentions and suspicions on Sister James in the confines of her principal’s office. Ryan’s Sister Aloysius is a martinet who runs a tight ship with a stern, icebox demeanor. In her spot-on, nuanced portrayal of the nun, Ryan never shines forth Christ’s light and love and remains largely an emotionless cipher until the conclusion. To her credit, Ryan never pushes Sister Aloysius’s austere attitude over the edge, but breathes feeling and life into her persuasiveness and her determination with fervency.

On the other hand, Father Flynn (Liev Schreiber) the priest, who is the pastor of St. Nicholas, manifests an openness, intelligence, flexibility, forward thinking personality and sense of irony. He and Sister Aloysius appear to be opposites in character, though both fabricate and lie; Father Flynn to drive home themes in his sermons, Sister Aloysius to “get at” the truth. The lighthearted, yet controlling Father conducts the physical education program and religion at the school. Both Sister Aloysius and Father Flynn follow the hierarchy and answer to the Monseigneur. This remains an obstacle for Sister Aloysius because she deems the elder cleric “other worldly” to a fault. She tells the young neophyte Sister James (Zoe Kazan), that he “doesn’t know who the president of the United States is.” Yet, here men rule.

A problem for the manipulative, coercive Sister Aloysius, the Monseigneur will dismiss any issue she brings to him, unlike another cleric she confided in at St. Boniface who believed her word and got rid of a priest Sister Aloysius implies was a pederast. Suspicious about Father Flynn, and questioning the personal purpose of his sermon about “doubt,” Sister Aloysius picks at Sister James like a feather pecking chicken who dominates hens by pecking them to draw blood because she enjoys its taste.

Preparing her victim for maximum influence, Aloysius criticizes Kazan’s Sister James. She derides her showboating as a teacher, her enthusiasm about her subject, her kindness to the students. She discourages Sister James’ relaxed atmosphere in her classes. After reducing the young nun to tears, she directs the neophyte to be emotionless and watchful about anything untoward. We learn later, as Sister James confides in Father Flynn, that the older nun has stolen her joy about teaching and has contributed to her bad dreams and loss of peace. This irony is not lost on us today, when religion is used as a hammer and sickle to browbeat and slice up the condemned populace to contort their lifestyles to politicized religious tenets popular over 120 years ago.

Sister James becomes the perfect foil for the imperious, commanding Sister Aloysius to manipulate and play upon in the tug of war between Sister Aloysius and Father Flynn. Initially, the “war” appears grounded in a difference in philosophies and life approaches between progressivism vs. conservatism. However, the divisiveness between them takes a sinister turn and explodes as Sister Aloysius gives rise to her suspicions that Father Flynn is grooming Black student Donald Muller for pederasty by giving him alcohol in the sacristy. It is an accusation that is proven only in her imagination.

Sister James is like a deflated ball tossed about in the storm that rages between Sister Aloysius’s determination to expose and evict Father Flynn from the church and Father Flynn’s insistence he is telling the truth and has done nothing wrong. In a climactic scene between them, Flynn’s denials and pleadings with her to count the cost to Donald, him and herself and to amend her convictions and threats because of a lack of proof, go on deaf ears. She has converted herself into the “anointed.” She would make those of the Inquisition proud, except they never would listen to a female.

To complicate the matter Sister Aloysius meets with the Black child’s mother, Mrs. Muller (the superb Quincy Tyler Bernstine). Mrs. Muller expresses that she is thankful Father Flynn has become her child’s protector. If Donald stayed in his previous school, he “would have been killed” by the bullies. Sister Aloysius dismisses Mrs. Muller’s backstory about her son’s beatings by his father for “being that way.” Instead, the principal is self-righteous and gratified that her determination has led to Donald Muller’s being dismissed from the Altar Boys, which Mrs. Muller explains devastated Donald.