Category Archives: NYC Theater Reviews

Broadway,

‘Games’ by Henry Naylor, Winner of the 2019 Adelaide’s Critic Circle Award

(L to R): Renita Lewis, Lindsay Ryan in ‘Games,’ written by Henry Naylor, directed by Darren Lee Cole (courtesy of the production)

Games the multi-award winning play by Henry Naylor directed by Darren Lee Cole codifies a time in history that resonates with us today. The play exposes the noxious practices of discrimination, racism, injustice and inequity during the backdrop of the 1936 Berlin Olympics held in Germany.

At that time Hitler was in power and was establishing his Aryan race laws against Jews who were being discriminated against in every aspect of society and government, from civil service positions to university jobs and private businesses. Hitler’s destructive social policies led to untold misery and horrific genocide. The ultimate tragedy was in the loss of human talent, brilliance and genius that most probably would have added to music, culture, the arts, sports and scientific advancements for the betterment of the world.

To explore how the initial race laws could impact a particular arena, Naylor highlights the world of sports and the Third Reich in the early stages of Hitler’s rise before the conceptualization of the Final Solution (the organized conspiracy to exterminate “undesirables,” specifically Jews, Gypsies, communists, etc.). Naylor indicates how the race laws destroyed the careers of two Jewish women who were incredible athletes and deserved the glory they should have gotten if not for Hitler’s wickedness.

Lindsay Ryan in ‘Games,’ written by Henry Naylor, directed by Darren Lee Cole (courtesy of the production)

The play, currently running at the Soho Playhouse, explores the true story about world class athletes, one in fencing, Helene Mayer, and the other in the high jump, Gretel Bergmann. The fascinating production, through interchanging direct address narratives, familiarizes the audience with another example of how Nazism not only harmed others but nearly annihilated the once venerable German culture and society.

The minimalistic production briefly chronicles the exceptionalism of Mayer and Bergmann and reveals how they worked with assiduous effort to achieve a greatness in their chosen sports. Mayer portrayed by Lindsay Ryan and Bergmann depicted by Renita Lewis take turns sharing their stories engaging the audience as their confidantes. Each woman discusses how she endeavored to become the best. Both share salient details about their struggles to excel at a level not achieved before by women in their respective fields.

Lindsay Ryan in ‘Games,’ Soho Playhouse, directed by Darren Lee Cole, written by Henry Naylor (photo courtesy of the production)

Helene Mayer, a German Jew was a phenomenon at 10-years-old. She sparred with male fencing partners after she sneaked into an all-male fencing class and convinced the teacher that she could best whomever she went up against. Encouraged by her father who was a doctor, Mayer achieved such a mastery in her skills that she won awards in competitions across Germany. Eventually, she won an Olympic gold medal at 17 at the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam, representing Germany. She won 18 bouts and lost only 2, bringing glory to Germany and receiving accolades from President Hindenburg.

Mayer’s story dovetails with Bergmann’s who was younger and who looked up to Mayer as her hero and inspiration. Indeed, she had a Mayer doll and was overwhelmed when she had the opportunity to meet with Mayer at her school where Mayer encouraged her to continue to excel as a track and field athlete.

During her segments of the play, Mayer discusses how she is ready to secure the Olympic gold medal a second time. However, when she receives disturbing news, her dedication and focus blows up and she doesn’t fulfill get the Gold. Sadly, by the time she worked to compete in the 1936 Olympics, she was banned from being on the German team because she was Jewish. The only team the Third Reich allowed her to be on was the equivalent Jewish team. She could not mingle with the “Christian” team, though she was well liked and spoke to everyone.

During the Bergmann exchange in the production, we discover that the same happened with Bergmann. Encouraged by her parents, as Bergmann, Lewis declaims enthusiastically that she eventually went to London and studied at London Polytechnic, where she became the British high jump champion. She also discusses how she was brought back to Germany to compete in the Olympics and save face with the Western World who received condemnation for discriminating against Jews. It is when she was preparing for the 1936 Olympics that the climax of the production occurs, Bergmann meets Ryan once more. They hadn’t seen each other since Bergmann’s high school years and Mayer’s visit.

Renita Lewis in ‘Games,’ directed by Darren Lee Cole, written by Henry Naylor (courtesy of the production)

At the last minute, in fact two weeks before the Olympics, Bergmann was prevented from competing because of her religion, though it was given out that she had physical ailments that prevented her from competing. The irony is that the Third Reich was so rabid in its annihilating policies, the Nazi party gave up the advantage of a good chance to win a medal only in order not to have to accept a Jew onto their team. For the Third Reich, it would have been more of a disgrace to have a “Jew” be recognized as a great star athlete, a fact that would have disproved the Nazi FALSE FACT that Jews were an “inferior race.”

Things fared differently for Mayer. As a token gesture to mollify the United States, German authorities allowed the half-Jewish fencer to represent Germany in Berlin primarily because she was on record as having won an Olympic medal in 1928 and was venerated nationally. She had been studying at Mills College in California and returned for the games. No other athletes of Jewish ancestry competed for Germany, except Mayer who was forced to compromise and give the Nazi salute as did the other athletes. Interestingly, in the play, Naylor has Mayer affirm that she is apolitical and cannot be branded. Above all she swears that she is a fencer not supporting or working against Hitler. However, fact checking reveals that she was used by Hitler and that is why she saluted, a compromise for her to compete in her love of fencing.

Games is largely expositional with character actions of fencing moves and graceful running moves threaded in by the very fit actors. It may also be viewed as two largely solo performances for there is little interaction between Mayer and Bergmann which is why their meet up in Bergmann’s high school and at the Olympics preparation was dynamic. Ryan and Lewis do a fine job in relaying the angst that Mayer and Bergmann went through in their emotional trials to shore up their determination against the Third Reich and in their struggle to compete and be the best.

Lindsay Ryan, Renita Lewis in ‘Games,’ written by Henry Naylor, directed by Darren Lee Cole (courtesy of the production)

The themes are exceptional. And Naylor rings out a siren call for us today in regard to holding on to the following tenets so as not to fall into the abyss that Germany fell into under Hitler’s Third Reich. We must strongly affirm our democratic values by upholding a free press, and upholding what makes our government strong- checks and balances. This is especially so against a current failing White House executive that smells of fascist-type dictatorship and one-man rule of the nightmare that led to Germany’s downfall, and can lead to the dissolution of our nation if allowed to go unchecked. Finally, Naylor decries that ultimately the discrimination meant to hurt the group discriminated against, ultimately destroys the discriminators.

Kudos goes to the actors, director and writer for capturing history for us and translating it into a vital remembrance that resonates for us today. Kudos also goes to the creative team of Jared Kirby (fight choreographer) Carter Ford (lighting design) Hayley Procacci (sound design) that helped bring Mayer’s and Bergmann’s stories into the present.

Games is a must-see if you enjoy learning about incredible world class athletes largely unknown today, but who should be recognized for their pluck, drive and accomplishments. Games runs at the Soho Playhouse (15 Van Dam Street) with no intermission. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

‘Slave Play’ by Jeremy O. Harris, An Explosive, Archetypal Look at Power, Sadomasochism and Oppression Through the Mythic Lens of “Black” and “White”

(L to R): Ato Blankson-Wood, Chalia La Tour, Joaquina Kalukango (kneeling), Irene Sofia Lucio, Sullivan Jones, Annie McNamara, Paul Alexander Nolan, and James Cusati-Moyer. in ‘Slave Play’ by Jeremy O. Harris, directed by Robert O’Hara (Matthew Murphy)

Slave Play by Jeremy O. Harris is a mind-bending, brain-slamming earthquake which will strike your soul and disturb you emotionally. Despite your desire to remain unaffected, you will react. Good live productions stir us. The finest plays rock us off our complacency and shatter our intellectual stasis. Slave Play, directed by Robert O’Hara, currently at the Golden Theatre, does that and more. Memorable and profound, it is the epitome of its sardonic genre. And in its ancient modernism, it rises to a level that melds tragedy and comedy.

The searing truths that run through Harris’ themes confound to a new clarity, especially if you see yourself as color blind and gender blind. Harris gouges out our assumptions and parades them in front of our unwillingness to perceive our hidden feelings about race, sex and power, teasing us in the process. By gaming his audience, Harris is all about stopping the games and taking off the masks. And he achieves this through the gyrations of his characters, three mixed-race couples who have sought therapy for their anhedonism (inability to feel pleasure-a symptom of depression and other ailments) with their partners.

The three couples sign up for “Antebelleum Sexual Performance Therapy” in order to expurgate their conflicts concerning race and sex that are ancient unconscious impulses or lesions borne from centuries of oppression in America from before the Civil War. It is an oppression that is in “black” and “white” unconsciousness that transcends skin color because the current society has historical remnants of the degradation of the “peculiar institution” which deformed the psyches of both masters and their slaves, the oppressors and the oppressed. Each couple suffers from these hidden twisted notions that they have ingested from living in American society. It has impacted them and they want a release from their suffering which manifests as alienation from their long-term partners.

This is a spoiler alert!

Joaquina Kalukango, Paul Alexander Nolan in ‘Slave Play,’ by Jeremy O. Harris, directed by Robert O’Hara (Matthew Murphy)

Only, you don’t know that at first. Indeed, initially as the play opens, we believe we are watching a scene from the antebellum South involving the abuses of the master slave relationships via sexual sadomasochism. With these scenes highlighting the sexual “play” of the marriage partners, Harris hits us between the eyes and in the core of our presumptions in the hope of laying bare the psycho-sexual racial myths that lurk in our souls.

Thus, everpresent in the scenic design by Clint Ramos is the plantation mentality: the desire to oppress and degrade employing the vehicles of sex. Using mirrors Ramos reflects the white southern archetype of the white antebellum plantation of Master MacGregor’s mansion that encircles the proscenium. Throughout most of the production, the projection of the white plantation remains in the background, symbolizing that we may think we have been released from our history, but it resides just below the surface of consciousness in our relationships and especially in our relationships with members of another race concerning issues of true intimacy and honesty.

It is in this plantation setting that the characters dig in to expose their sadomasochistic impulses from a racist past that they have unconsciously internalized and must expiate to heal their marriage relationships. Harris humorously twits the audience’s assumptions about black sexual prowess and sensuality in the opening scene with each mixed race couple as they play out their fantasies to free themselves of the bondages that hamper reaching a satisfying closeness with their partners.

Gary (Ato Blankson-Wood) and Dustin (James Cusati-Moyer) portray the gay couple who cannot please each other. They engage in the fantasy of master/slave verbal abuse donning fictional characters, Dustin as an indentured servant and Gary as a slave who has been put in charge of him. Through the play acting, Gary reaches fulfillment but in his response to this, he upsets Dustin. There is only a partial breakthrough, tenuous at best. They have not exorcised the notions that harm them.

(L to R): James Cusati-Moyer and Ato Blankson-Wood in ‘Slave Play,’ written by Jeremy O. Harris, directed by Robert O’Hara (photo by Matthew Murphy)

Phillip (Sullivan Jones) and Alana (Annie McNamara) portray a married couple who cannot achieve a hot intimacy until they enact their antebellum sex play. In their fantasy Alana is Master MacGregor’s wife and Phillip is her house slave who does what she wants. What pleases her is to take over the masculine role while he takes on the feminine role during a sexual encounter, something which makes her freer for intimacy with her partner. However, they too have issues because of Phillip’s race identity problems which he is loathe to admit and which to him are invisible.

The couple Kaneisha (Joaquina Kalukango) and Jim (Paul Alexander Nolan do not progress on this fourth day of the sexual fantastic. Jim finds the therapy ridiculous and demeaning. Ironically, it is Kaneisha who has engineered the roles and takes the lead in their improvisation. She portrays the slave and Jim (who has a British colonial accent-another irony) is the overseer who commands her unjustly, then sexually uses her as she uses him. But Jim finds her fantasy an impossibility and will not subject himself to it. Is this not a case of subliminal control and domination over his wife Kaneisha?

With each of the couples’ fantasies, there are strong elements of sadomasochism which are supposedly exorcised in the service of removing blocking psychic layers that impede the couples’ pleasure with each other. Unfortunately, Jim has stopped the process for all the couples. A condition of the therapy they have all agreed to is that if one cannot continue, all must not continue. When the couples meet to discuss and analyze what they felt during their fantastic sexual exploits exposing their sub rosa “plantation” mentality, the conflict is on. And Harris’s characterizations continue on a profound and humorous track as problems arise. Each couple ends up confronting their partner with results that are both humorous and poignant.

At this juncture social scientists and therapy guides Patricia (Irene Sofia Lucio) and Tea (Chalia La Tour) attempt to analyze and reaffirm their subjects’ positive changes as a result of the antebellum sexual play therapy. That the researchers do this in a controlled, manipulative way is an irony considering that all seek freedom from their internalized racial oppressions (the predator/prey elements of human behavior). Harris sardonically reveals these individuals, including the scientists, may be duping themselves into believing they’re getting closer to a “clear,” when what they seek cannot be achieved in a week-long process, regardless of how extreme the interventions. Perhaps, what has been internalized must be overthrown with individual introspection on the part of both partners after a long period of time. There is no quick fix except sustained love, growth, patience, understanding and the will to be close which eventually, through loving practice, will manifest. Maybe.

Annie McNamara and Sullivan Jones in ‘Slave Play,’ written by Jeremy O. Harris, directed by Robert O’Hara (Matthew Murphy)

The “liberal” posture which infects the “white” characters who are coupled up with their “darker” equally infected counterparts Harris explodes by the play’s end, as he disintegrates the notion that racism’s complexities may be dealt with through extreme interventions and quickie therapies. Especially for couple Kaneisha and Jim there has been a break through in their relationship at great cost to Jim who upon facing himself, dislikes what he perceives himself to be. Whether they continue together after this turning point doesn’t matter. Each have understood a soul revelation and will never be the same again.

Harris’ Slave Play instructs us about our perceptions, our attitudes and our willingness to go to that place that is uncomfortable to shed the pretense and stop pandering to faux racial equanimity and justice. That is why the curtain mirror that reflects the audience’s faces effected by Clint Ramos’s superb scenic design is a clever touch in keeping with Harris’ themes. The more visible reflections are for the audience members who are down front in the expensive seats.

Shouldn’t we examine our own proclivities and assumptions about sex, race and power dynamics? Or should we just ignore that there is a confluence of currents roiling in the subterranean waters of our souls about race? How do we overthrow our past and live freely without internalized cultural oppressions: misogyny, paternalism, institutional racism, body objectification, appearance fascism, sexism, chauvinism, reverse racism and impulses of white supremacy which move along a continuum from faint to furious? All of these oppressions impact our intimacy with ourselves and others, whether we are in mixed race relationships or not. Harris suggest we investigate these tantalizing questions which are not for the faint of heart.

As Americans steeped in a social history of racial power dynamics that continue today, though many are loathe to admit it, one cannot view this play as a light observer. To have the themes resonate, one should follow the characters to the most profound levels and then consider the myths, the conceptualizations about being black, white and gradations of both culturally. One must see with new eyes what has not been seen before at this crucial time when leaders speak to and embrace racist hate groups (KKK, Neo Nazis, etc.) curry favor with the likes of David Duke and Richard Spencer, and give political advisors like Steven Miller great power and moment over US Immigration policy with the precise intent to discriminate, promote fear and abuse for political purposes.

(On Ground L to R): Ato Blankson-Wood, James Cusati-Moyer, Sullivan Jones, Annie McNamara, Joaquina Kalukango, Paul Alexander Nolan. (In red boxes L to R): Irene Sofia Lucio and Chalia La Tour, ‘Slave Play,’ directed by Robert O’Hara, written by Jeremy O. Harris (Matthew Murphy)

Harris intends to shock us into a dialogue to confront our own assumptions on whatever level we can, so we might grow as Americans who recognize their rich yet horrific social, political and cultural history. As Harris’ characters recognize they are stymied and self-harmed by their own misconceptions, depressions and failures to deal with the historical, ancestral folkways and noxious human behaviors they’ve internalized, at least they attempt to overthrow them. Shouldn’t we, Harris suggests? But are we up for this? We should be! Look at the gun shootings at synagogues and black churches.

Until there are conversations about such controversial topics as Slave Play raises, the country’s divisiveness may be exploited by pernicious leaders and malevolent foreign intelligence services who foment racial hatreds to satisfy their own personal agendas. Our culture’s current divides are toxic. To mitigate them requires a complexity of understanding and introspection on a personal level. Harris indicates dealing with this on an interracial, mixed couple level may be the way to get there if there is love, patience, understanding and will. The issues are hyper complex and are not adequately answered by quick fixes and exotic hyperbolic interventions which themselves represent the internalized predator/prey, oppressor/oppressed remnants of racism.

The ensemble is wonderful and acts seamlessly together with a comfortability at behaviors which appear impossibly raw. The therapy session is particularly acute, funny, authentic and smashing. All the actors are standouts as is required with such an amazing play. Kudos to the director who shepherded them. Each couple ends up confronting their partner with results that are both humorous and poignant.

The design team also shines: Dede Ayite (costume design) Jiyoun Chang (lighting design) Lindsay Jones (sound design & original music) Cookie Jordan (hair & wig design). Conceived at New York Theatre Workshop where it ran in from November 2018 to January 2019, Slave Play has come to Broadway where it is provoking consternation, confusion and revelation. It runs with no intermission until 19 January. There are too many reasons why you should see this play if you are an American, and especially if you have a bit of residual racism within and are adult enough to laugh at yourself. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

‘Sunday’ by Jack Thorne, Directed and Choreographed by Lee Sunday Evans

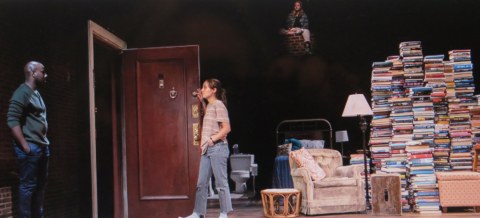

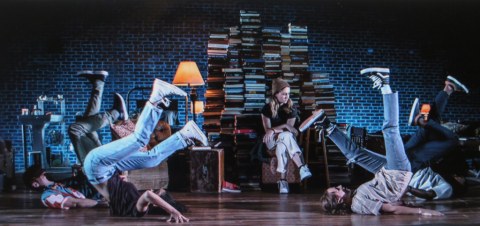

(L to R): Christian Strange, Sadie Scott, Ruby Frankel, Zane Pais, Juliana Canfield in ‘Sunday,’ written by Jack Thorne, directed by Sunday Lee Evans (Monique Carboni)

Sunday by Jack Thorne, directed and choreographed by Lee Sunday Evans is a striking look at youth in its misery and glory. Thorne, best known for his success with Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, doesn’t take the easy road in this play which melds narrative, action and dance sequences to reflect all that we need to know to understand Thorne’s characters and the events that happen one Sunday evening to impact their lives. The dance sequences representative of the energy and vitality of the characters provide a much needed contrast throughout thanks to Lee Sunday Evans (Dance Nation-Obie, Lortel awards) who also directed.

Maurice Jones, Sadie Scott in ‘Sunday,’ written by Jack Thorne, directed by Sunday Lee Evans (Monique Carboni)

The active narrative by Alice (Ruby Frankel) summarizes a catch up history of the characters in the opening scene and particularly focuses on protagonist Marie (Sadie Scott shines in the second half of the play) an outlier and self-conscious, introvert. Alice comments on choice tidbits during the extended evening of drinking, talking books and sniping sub rosa insults, prefacing her commentary to shore up the audience’s attention about a character’s particular “defining moment.” She concludes her narrative with an epilogue reviewing how each character “turned out” decades later as a fascinating exclamation point.

Christian Strange, Juliana Canfield, Ruby Frankel, Sadie Scott, Zane Pais in ‘Sunday,’ written by Jack Thorne, directed by Sunday Lee Evans (Monique Carboni)

As we reflect on their interactions in present time, we have a superficial glimpse into how they may have evolved to their final result in the future. But this is in retrospect; hindsight is an exact science. We learn what they “have become” at the play’s conclusion.

The only character who has substance so we may empathize with her is Marie. But between the past and the future which Alice relates is the shadow of present time, a Sunday evening party among “friends.” As we watch the “major” event unfold, Thorne relates an important theme of the play. Human beings rarely live in the present moment to understand how that moment has a particularity all its own. Nor do they understand how it leads to the next and next in the series of the rest of the moments of their lives. Only when there is acute pain and a shattering soul earthquake do they turn on an axis to remember the jump off point into another development in their life’s journey.

Maurice Jones, Sadie Scott in ‘Sunday,’ written by Jack Thorne, directed by Lee Sunday Evans (Monique Carboni)

On this particular Sunday evening, Marie experiences an event and responds to create a sea change in her life which she propels in one direction, a return to home for solace and comfort. Thorne shows us the how and why of it. Meanwhile, the other characters, especially Bill are the backdrop against which Marie batters herself into an awakening to change the direction of her life.

(R to L): Juliana Canfield, Christian Strange, Sadie Scott in ‘Sunday,’ by Jack Thorne, directed by Lee Sunday Evans (Monique Carboni)

Evans has staged Alice above the fray to comment on the action and characters as she sits with a lone spotlight in the dark on piles of books, then comes down to join the others for the party. The books are a quasi dividing wall in Marie’s and Jill’s apartment n New York City where they live and work and have their book sessions. Perhaps the book wall is an intellectual symbol to keep others out. It is an intriguing set piece. On this evening right before they gather, Bill (the excellent, Maurice Jones whose vibrance carries the second part of the play) the neighbor stops by and tells Marie he can’t join her for the party since he works the next day. He also asks Marie if she can keep the music down.

(L to R): Ruby Frankel, Juliana Canfield, Zane Pais, Sadie Scott, ‘Sunday’, directed by Lee Sunday Evans, written by Jack Thorne (Monique Carboni)

From the time the others join in and have their discussions about the book of the evening and more, we learn salient pieces of information about each of them. The conversation is not earth shattering, the wisdom is not in abundance and the self-indulgence is obvious. Jill and Milo are an item and express their affection. Marie doesn’t appear comfortable. As she recently lost her job because she doesn’t “fit in,” it seems that she now carries this mantle into the party. Though her strong friendship with Jill (Juliana Canfield) is a boon, Milo (Zane Pais) appears to be jealous and resentful, especially toward the end of the evening as he insults Marie. Keith (Christian Strange) rounds out the group of drinkers adding his opinions.

(L to R): Christian Strange, Sadie Scott, Ruby Frankel, Zane Pais in ‘Sunday,’ directed by Lee Sunday Evans, written by Jack Thorne (Monique Carboni)

The most pleasant session of the first segment of the production is the dance sequence. A few times the group break into a dance to express their inner emotions, yearning to escape from their lives of boredom and sameness. The actors have convinced us outright of the stasis and purposelessness of their lives. Thus, the dances are a breath of fresh air. Indeed, more could be added to break up the monotony of talking heads who slide past each other without really looking for the uniqueness or resonance of each other’s humanity.

(L to R): Sadie Scott, Zane Pais, Ruby Frankel, Juliana Canfield, ‘Sunday’, Jack Thorne, Lee Sunday Evans (Monique Carboni)

As the evening comes to a close and the others leave, Marie falls apart and weeps for her miserable self. Her self-recriminations spiral her into an emotional refuse pile of self-loathing. For solace she calls Jill to come back and spend the night with her away from Milo. When the knock comes at the door, we are relieved to see it is the interesting Bill who makes his way into her apartment stating he couldn’t sleep.

The scene between them evolves with humor (Maurice Jones’ timing is spot-on). And there is a sensual tension that holds promise stoked by Marie who is desperate to make human contact so that she won’t feel so alone. Ironically, it is she who is the one who pushes the sex on Bill. And it is he who avers and attempts to slow the situation down to get to know her better. A writer, he eventually shares his novel’s plot. Indeed, he is one with whom she could, if she is ready, establish a lasting, sensitive relationship with. Thorne gives us this clue when Bill responds to her question what is it that he likes about her. Bill’s answers are poetic, profound, lovely. However, Marie in loss and confusion pushes the sex, demeaning Bill’s ethos and being. Clearly, her devastation and emptiness cannot recognize who Bill is and the soul clarity he can offer her.

Sadie Scott, Juliana Canfield, ‘Sunday,’ written by Jack Thorne, directed by Lee Sunday Evans (Monique Carboni)

The ending and the epilogue follow fast and we are disappointed. We understand that the human factor takes over. Marie fails to seize the opportunity for love that stands in front of her. Allowing the morass of self-loathing to overwhelm her, she chooses a path of retreat. In the epilogue that April matter-of-factly delivers, we discover how she lives the rest of her life from then on, materially. Whether her soul spark resurrects, April does not delineate. The sense of loss of human creativity and opportunity for something marvelous in the lives of these characters, regardless of their bank accounts, overwhelms.

(L to R): Zane Pais, Christian Strange, Ruby Frankel, ‘Sunday’, directed by Sunday Lee Evans, written by Jack Thorne (Monique Carboni)

Thorne’s play is about so much more than youth grappling with identity in a chaotic world. It is about the soul and the spirit missing the tremendous chances offered which are not taken up or recognized. Fear and self-restriction in the protagonist Marie as everywoman looms in everyone’s lives. To break beyond self-loathing, purposelessness, misery and disappointment takes courage and persistence. It is easy to return to a place of comfort which neither challenges nor stimulates us to be different. Thorne’s themes resonate not only for this age group, but for every stage every age group. Boredom is not an option, nor is self-loathing as long as there is life. As Thorne suggests, we define the moments in our lives when we control the narrative. It is when we allow others to define who and what we are that we become lost.

The ensemble of ‘Sunday,’ written by Jack Thorne, directed by Lee Sunday Evans (Monique Carboni)

The play is slow moving in the beginning to exact Thorne’s themes and for the dance scenes to represent the great contrast in the inner souls of the characters who find dance their purpose and form of expression. Also, the contrast between the younger characters’ callowness and Bill’s wisdom, likeability, sensitivity and grace (so beautifully rendered by Maurie Jones) pops because the ensemble is by nature invisible emotionally with the exception of Marie. The scene between Jones’ Bill and Scott’s Marie is smashing and worth a look see for the acting, writing and direction.

Sunday features scenic design by Brett J. Banakis, costume design by Ntokozo Fuzunina Kunene, lighting design by Masha Tsimring, sound design by Lee Kinney, original compositions by Daniel Kluger

Sunday runs with no intermission at Atlantic Theatre Company (West 20th Street between 8th and 9th) until 13th October. See it before it closes. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

‘Heroes of the Fourth Turning’ by Will Arbery at Playwrights Horizons

Jeb Kreager, Julia McDermott, Heroes of the Fourth Turning by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

John Zdrojeski, Julia McDermott in Heroes of the Fourth Turning, by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

It’s seven years after you’ve graduated from college. What do you do if you are adrift, emotionally miserable and/or in physical pain? What if cocaine, alcohol, social media obsessions, abstinence from sex, indulgence in sex, and your Catholicism isn’t helping you find your way? Do you find something else to believe in to help you escape from the labyrinth of conundrums and foreboding demon thoughts plaguing your life?

Will Arbery’s Heroes of the Fourth Turning in a production at Playwrights Horizons ably directed by Danya Taymor discloses the inner world of the right wing religious. In his entertaining and profound examination of conservative-minded friends and alumni from a small, Catholic college who gather for a party, we get to see an interesting portrait of conservative “types,” who are akin to liberals in dishing the rhetoric. To his credit Arbery gives grist to the argument that beyond the cant are the issues that pertain to every American. Whether liberal or conservative, all have the need to belong, to care and love, and to make a way where there is no apparent way to traverse the noise and cacophony that creates the social, political divide currently in our nation.

John Zdrojeski, Zoë Winters Heroes of the Fourth Turning, by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

How each of the friends attempts to survive “out there” in the cruel, “evil” world fascinates. During the evening mini reunion on the occasion of celebrating Emily’s mom’s accepting the presidency of their alma mater, Emily (Julia McDermott), Kevin (John Zdrojeski), Justin (Jeb Kreager), and Teresa (Zoë Winters), explain who they’ve become or not become in the seven years since they’ve graduated. Teresa, a rebel during her college years, has become more right-wing conservative than ever, embracing Steve Bannon, Breitbart and Trump with gusto. The others have “laid low” in retreat in Wyoming and Oklahoma, holding jobs they either despise or “put up with,” until they get something better.

Zoë Winters, Jeb Kreager, Julia McDermott, Heroes of the Fourth Turning, by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

Zoë Winters portrays Teresa, the feisty, determined, “assured,” conspiracy-theorist supporter with annoying certainty and hyper-vitality, as she explains the next phase of American history to the others. She does this by summarizing a book which posits the Strauss-Howe Generational Theory. Emily, Teresa and Kevin fit into the millennial segment which lends its title to the play: the fourth turning/hero cycle. As she insists that her friends are the hero archetypes laid out in Generations: The History of America’s Future: 1584-2069, she suggests they must embrace their inner/outer hero and get ready for the coming “civil war.”

John Zdrojeski, Julia McDermott in Heroes of the Fourth Turning by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

For different reasons Emily and Kevin find Teresa’s explanation of the “Fourth Turning” conceptualization doubtful for their lives. Kevin’s self-loathing and miserable weaknesses belie heroism. He is too full of self-torture and denigration to get out of himself to help another or take a stand for a conservative polemic to fight the liberal enemy in a civil war. Emily is crippled by the pain of her disease. We discover later in the play that she has questions about the conservatism she once embraced. The civil war polemic only seems possible for Justin (Jeb Kreager), who was in the military. Though Justin is not the “Hero” archetype, but is a “Nomad,” he later in the evening expresses that he thinks the conspiracy mantra “there will be a civil war,” proclaimed for decades by alternative right websites will happen.

John Zdrojeski, Zoë Winters, Jeb Kreager, Michele Pawk, Julia Mermott in Heroes of the Fourth Turning by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

Arbery has targeted their conversations with credibility and accuracy and the actors are authentic in their nuanced portrayals. As Kevin, John Zdrojeski becomes more drunk, humorous and emotionally outrageous as the night progresses. His behavior shocks for a supposed Catholic, until we understand Kevin doubts his religion’s tenets, especially abstinence before marriage. To a great extent he has been crippled emotionally by doubt, double-mindedness and the abject boredom he experiences with his job in Oklahoma. Also, he admits an addiction to Social Media. Zdrojeski projects Kevin’s confusion and self-loathing victimization with pathos and humor. But we can’t quite feel sorry for him because he is responsible for his morass and appears to enjoy reveling in with his friends. Teresa suggests this is his typical behavior.

The friends wait for the arrival of Gina (Michele Pawk), Emily’s mom’s, to congratulate her on becoming president of their old alma mater, Catholic Transfiguration College of Wyoming. As they wait, they drink, get drunk and catch up with each other, reaffirming their friendships from the past. They discuss and reflect upon the decisions that brought them to Catholic Transfiguration College. We note their conservative, religious views about life, family and politics. Their confusion, sense of impending doom and lack of hope for the future are obvious emotional states. This is an irony for Catholics, whose hope should reside with the birth of Christ and the resurrection. Clearly, they are not exercising the spiritual component of their faith, alluded to in Gina’s speech and in Kevin’s quoting of Wordsworth’s poem “The World is Too Much With Us.” They’ve allowed the material and carnal to overtake the spiritual dimension and thus are depressed and filled with doubt.

(L to R): John Zdrojeski, Michele Pawk, Jeb Kreager, in Heroes of the Fourth Turning by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

In representing the conservative views of these individuals, the playwright culls talking points from right-wing media and blogs which Teresa references to Gina when Gina finally arrives. The fact that right-wing conservatism construes violent fighters as heroes is a conflated, limited view. Indeed, to see oneself as a hero and embrace that role is not even an act which true heroes (i.e. firemen, doctors in war zones) saving lives perceive for themselves. It is rhetoric. And Teresa, to empower herself and impress her old friends, speaks it as polemic. Her discussion is not really appropriate to inspire comfortable light conversation at a party. Indeed, her talk is done to solidify herself in the firmament of fantastical belief and remove any oblivion of her own doubts about her life. She and Justin who was in the military particularly rail against liberals, the LGBTQ community, Black Lives Matter, etc.

(L to R): Michele Pawk, John Zdrojeski, Zoë Winters, Heroes of the Fourth Turning, by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

Interestingly, Gina blows up Teresa’s cant when she finally arrives to receive the friends’ congratulations. However, they are not quite ready for Gina’s rhetorical response which is a convolution of conservative and liberal ideas that loop in on themselves again and again and defy political labeling. But Gina separates out the illogic of each of their positions. She disavows Justin’s need for guns on campus and decries the conspiracy of the upcoming “civil war.” She implies that Bannon and his like-minded are hacks, and she disavows Trump to the shock of Teresa. At the end of the evening, she pronounces that she is disappointed in the education they have received at their school, believing the college has failed them.

Jeb Kreager, Julia McDermott, in Heroes of the Fourth Turning by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

The night of celebration becomes a night of upheaval for Emily, Justin, Kevin and even the staunchly “certain” Teresa who will in the next decade most probably change her views a number of times to suit her determination that she has a handle on the great narrative of “reality.” But in truth as we watch these friends founder through the labyrinth of sublimely complex political, social and cultural convergences they discuss and refer to, it becomes obvious that they have been dislocated from their comfortable conservatism that categorically defined the world for them when they began college.

(L to R): Zoë Winters. Michele Pawk in Heroes of the Fourth Turning by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

The irony is that when Gina comes and joins their conversation and smacks down each of their beliefs, especially Teresa’s, we settle back watching the imbroglio that Arbery has wrought. Indeed, we wonder at Gina’s convoluted logic and justifications. That she would give Kevin a job in admissions is a dark irony of misjudgment. He appears the least directed to help others in the admissions process. Though they say their goodbyes with love, Justin and Emily remain in darkness. There is no comfort to be found. There is only the continuation of a foreboding reckoning.

The strongest dynamic of the play resides in the conflicts when Arbery has the friends go at each other after their initial easy reaffirmation of friendships. Ironically, the community they attempt to create falls apart driven by what is devouring each of them inside. It is then that personal flaws they’ve discussed manifest and the hell they face within spills out. Justin’s is humorously eerie. Emily’s comes in the form of fury at whom she deals with in her job and the resident demon of pain in her body. Teresa fears she is making a mistake getting married, and Kevin can’t come to the end of himself.

The tempest between and among the individuals and their inner conflicts reflects a currency for our times and is welcome fodder for entertainment. Arbery with the subtle direction of Taymor has succeeded in extending a hand across the divide of national uproar between left and right with his human, flawed characters. The actors in this ensemble are superb and hit powerful emotional notes with spot-on nuances between humor and profound drama.

This is a play you must see for its shining performances, its topics, the rhetoric-exceptionally fashioned by the playwright and its surprises in characterization. The conclusion is chilling as it expands to the mythic. Noted are the design team: Sarafina Bush (costumes), Isabella Byrd (lighting), Justin Ellington (sound), J. David Brimmer (fight director).

Heroes of the Fourth Turning runs with no intermission at Playwrights Horizons (416 West 42nd Street between 8th and 9th). For tickets and times go to their website by CLICKING HERE.

t

‘Dublin Carol’ by Conor McPherson, Directed by Ciarán O’Reilly at Irish Repertory Theatre

(L to R): Cillian Hegarty, Jeffrey Bean, ‘Dublin Carol’ by Conor McPherson, directed by Ciarán O’Reilly, Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

Dublin Carol by Conor McPherson directed with just the right tone and irony by Ciarán O’Reilly is a seminal play about the spirit of Christmas that is bestowed upon the principal character John, superbly portrayed by Jeffrey Bean. McPherson chooses this self-hating alcoholic protagonist to reflect humanity’s hope of redemption from broken promises, regrets and soul sins lathered with guilt and remorse.

McPherson’s John, like many, reveals an overarching longing for change from the boredom of self-loathing, loneliness and recriminations. During the course of the play we see how the playwright elucidates that such change never happens quickly, but does come with subtle, gradual almost unnoticeable shifts when least expected. In John’s instance it is the visit from his daughter Mary (Sarah Street) whom he hasn’t seen in ten years that fans the flames that have been ignited by his boss the mortician Noel who saved him from one stage of himself. When she comes to tell him about the condition of his wife, her mother whom he abandoned long ago, the conversation prompts his movement to admit his miserable state when he left the family. He was in hell.

Sarah Street in ‘Dublin Carol’ by Conor McPherson, directed by Ciarán O’Reilly, Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

Above all McPherson’s work is about love and forgiveness. Such love is given by John’s daughter. And it is an irony that John is so over-bloated with guilt and remorse that he cannot forgive himself and thinks himself completely unworthy of it. But it is her expression of love and respect (she admits she also hates him) that helps him make a final determination. The decision moves him toward a kind and thoughtful resolution with his family which by the end of the play portends a new door will open in John’s life that may lift him up from his self-hatred into self-forgiveness.

Though the setting is Dublin Christmastime, in the office of a funeral parlor where life and death sit side by side, the title references a widow Carol who lived in Dublin that John mentions he had a long-time affair with. The title also alludes to a Carol as a song heralding the good news of the celebration of Christ’s birth. Of course, Christ’s birth symbolizes that redemption, reformation, forgiveness and love are possible for the great and small and even someone as “rotten” as John perceives himself to be.

(L to R): Jeffrey Bean, Cillian Hegarty in ‘Dublin Carol’ by Conor McPherson, directed by Ciarán O’Reilly, Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

The characterizations are drawn clearly and we become engaged in the simple interactions between Mark (Cillian Hegarty) and John in the first segment, John and his daughter Mary in the second and John and Mark in the third. The arc of development grows out of these interactions and the nature of the conversations which become more revelatory and intimate bring about a change in John’s character.

As Mark and John sit down for tea and a respite from their labors assisting Mark’s sick Uncle Noel (a mortician) with the external arrangements of a young person’s funeral while Noel is in the hospital, we first learn about John and a bit about the twenty-year-old Mark. John shares his self-perceptions and generally blames his lack of discipline and care for his family because of alcohol. He enjoys drinking. But when Mark’s Uncle Noel gave him a job to help in the office with the funerals, John’s life improved and he lifted himself up from the bad state he was in when Noel met him.

Jeffrey Bean, Sarah Street in ‘Dublin Carol’ by Conor McPherson, directed by Ciarán O’Reilly, Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

John’s character grows on us because he holds little back and digs down into the depths of his self-loathing in each segment, taking off on a racetrack in his confession and heart-to-heart with daughter Mary to whom he apologizes for his miserable treatment and abandonment of the family. It is clear that there was no physical harm. Indeed, his own father beat his mother and John does not follow in his footsteps. Nevertheless, he lands on the fact that he didn’t stop his father and was a coward and felt self-hatred for selfishly, brutally not intervening because he feared getting beaten along with his mother.

However, even after John apologizes profusely for his behavior to Mary, he knows it isn’t enough. Clearly, he despises himself and wishes he could erase the memory of who he is along with his former identity and behaviors with his family. The self-disgust moves him to say he wishes he had never been born. Of course the more he admits fault, and makes such profound declarations, the more we identify with him and find his authenticity human, real and poignant. Jeffrey Bean is truly adroit in the role. He strikes all the notes clearly. He manifests John’s self-disgust with the nuance that John longs to be a different person, but is afraid he will let himself down by letting his family down once more.

Sarah Street, Jeffrey Bean in ‘Dublin Carol’ by Conor McPherson, directed by Ciarán O’Reilly, Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg

For their part Mary and Mark become John’s sounding boards, yet he clearly engages them and asks about their lives. When he discovers the news that Mary brings and the subsequent request that goes with it, the situation becomes a way that he can make up for his behavior in the past. He and Mary confess each other’s faults to one another, an important step toward forgiveness. But can John trust himself to do the right thing and stick to his decision? The irony is this: if he fulfills the request he will have to confront his past with the one he most abused and hurt, his wife from whom he never obtained a divorce. His guilt is overwhelming!

As his daughter leaves with the understanding that John will go with her to visit her mother who is dying, she importunes him not to drink any more and to be ready at a later time when she will drive him to the hospital. Of course, flashing lights go on. It is as if the request to not drink triggers John with perverse reverse psychology. The segment closes leaving John contemplating what to do. To drink? To make it up to his wife, daughter and son? Or just to escape somewhere out of their reach?

(L to R): Jeffrey Bean, Cillian Hegarty in ‘Dublin Carol’ by Conor McPherson, directed by Ciarán O’Reilly, Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

At the top of the third segment we discover John caves to self-loathing and guilt. He has been celebrating “Christmas.” Mark interrupts him only to discover John was too overwhelmed with drink to pick up his money at the bank. During the course of their interchange, John lays down a rant which is pure McPherson replete with irony and sardonic humor as he relates how his affair with Carol and her unconditional love drove him to the end of himself and the dregs of barrels of alcohol. At this point it is apparent, especially when he begins to put away the Christmas decorations that he has no intention of making it up to his family or going with his daughter. He is back to square one and will be on another bender and into the abyss without Noel to save him a second time.

McPherson’s characterizations and themes are spot-on. Throughout, this work is filled with dark humor which resonates in truthfulness. And in the hands of Jeffrey Bean guided by O’Reilly, the ironies spill out with fervor, especially in the last section of the play when John attempts to counsel Mark not to feel guilty about ending it with his girlfriend. John’s groveling diatribe about the stages of his drunks is also humorous. But the confession and John’s setting a terrible example for Mark does both characters good. Hearing the pain and misery of the stages of drunkenness would give anyone pause about drinking to oblivion.

Jeffrey Bean in ‘Dublin Carol,’ by Conor McPherson, directed by Ciarán O’Reilly, Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

The ensemble work is tight and O’Reilly keeps the production resonating with the wisdom and revelations that McPherson suggests in his themes. Kudos to the creative team who bring it all together: Charlie Corcoran (scenic design) Leon Dobkowski (costume design) Michael Gottlieb (lighting design) M. Florian Staab (sound design) Ryan Rumery (original music).

See Dublin Carol for the uplifting performances in this subtle and different McPherson work. It is running at Irish Repertory Theatre (22nd St between 6th and 7th) with no intermission. For tickets and times go to their website: CLICK HERE.

‘runboyrun’ and ‘In Old Age’ Two Magnificent Works by Mfoniso Udofia

Chiké Johnson, Patrice Johnson Chevannes in runboyrun and In Old Age, written by Mfoniso Udofia, directed by Loretta Greco, Awoye Timpo (Joan Marcus)

What is the impact of experiencing a genocidal civil war when one’s ancestry, bloodline and religion are used as targeted excuses for extermination? If one survives, is it possible to overcome the wartime horrors one experienced? Or is the sufferer doomed to circularly repeat the emotional ravages of past events that erupt from the unconscious and imprison the captive forever in misery? How is such a cycle broken to begin a process of healing?

In runboyrun, Mfoniso Udofia, first-generation Nigerian-Amerian playwright, through poetic flashback and mysterious revelation, with parallel action fusing the past with the present, explores these questions. Majestically, in her examination of principal characters Disciple Ufot (the superb Chiké Johnson), and his long-suffering wife Abasiama Ufot (the equally superb Patrice Johnson Chevannes), we witness how Disciple overcomes decades of suffering with the help of Abasiama during a night which is a turning point toward hope and redemption.

Chiké Johnson, Patrice Johnson Chevannes, Karl Green, Adrianna K. Mitchell in runboyrun and In Old Age, written by Mfoniso Udofia, directed by Loretta Greco, Awoye Timpo (Joan Marcus)

A bit of backstory is warranted. In 2017 New York Theatre Workshop presented two of Mfoniso Udofia’s plays in repertory (Sojourners, Her Portmanteau). runboyrun and In Old Age are two of Mfonsio Udofia’s offerings which are plays in The Ufot Cycle, a series of nine plays in total which chronicles four generations of a family of stalwart women and men of Nigerian descent. Though the plays currently presented at NYTW are conjoined to elucidate similar themes, they do not run in sequence. Nevertheless, both plays spotlight Mfonsio Udofia as a unique female voice of the African diaspora in the United States. Both represent the particularity of her exceptional work from a maverick’s perspective.

The first play directed by Loretta Greco begins with a flashback of a sister and brother. The setting is January, 1968 Biafra, the southern part of Nigeria that attempted to gain independence from Nigeria during the three year Biafran Civil War. During a lull in the shelling by the government in a hideout in the bush, the sister comforts her brother with a metaphorical story about the foundation of humanity and life. Then she encourages him to run as a game. However, it is the one activity that will save their lives as they escape the Nigerian soldiers at every turn, until they reach a safe place in a compound with their mother and brother.

Chiké Johnson, Patrice Johnson Chevannes, Karl Green, Adrianna K. Mitchell in runboyrun and In Old Age, written by Mfoniso Udofia, directed by Loretta Greco, Awoye Timpo (Joan Marcus)

This setting alternates to the present January, 2012, where we are introduced to the Ufots, transplanted Nigerians who immigrated to the United States, became citizens and eventually settled in the ramshackle interior of their colonial house in Massachusetts. However, from the moment Johnson’s Disciple enters their cold, dank home and with bellicosity relates to Chevannes’ Abasiama, we understand that their estrangement is acute. For her part Abasiama, who lies on the couch in the center of the living room wrapped up in layers of clothing with blankets and sheets thrown over her head, disengages from his behaviors, attempting to stay away from his weird, oppressive antics.

Disciple attempts to control her every move, berates and blames her for the bad spirits in the house. However, it becomes obvious that it is he who suffers derangement. He is fixated on the perception that everything outside him and especially his wife are the source of his bad luck and the wickedness that plagues him and threatens to upend his life and his writing. In what we learn has become a ritualistic practice, Disciple uses a thin stick to circumscribe areas as safe to prevent evil spirits from disarranging and unsettling his peace. Abasiama, used to this behavior, plays Christian music; Christianity was a part of their Igbo ancestry. However, after Disciple’s exorcism, when he attempts to begin work on a new book, the past erupts. Once more the playwright creates flashbacks which establish and explain Disciple’s instability and borderline insanity.

The full cast of runboyrun, written by Mfoniso Udofia, directed by Loretta Greco (Joan Marcus)

Udofia’s structure interlacing the past with the present is particularly strengthened by Andrew Boyce’s scenic design which threads the action, symbols and themes. The house is divided in a cross section symbolizing the division in Disciple’s and Abasiama’s relationship and marriage so we see how both conduct their lives in separate parts of the house: Abasiama upstairs, Disciple in the basement. They do not communicate, nor are they intimate with each other’s thoughts and feelings, sharing little if anything of their histories, a tragedy which has led to the disintegration of their marriage. Their lives are separately lived; they buy food separately, use different refrigerators. Disciple cooks for himself and they take their meals separately because he believes she may poison him.

The separation extends even to the different churches they attend and Disciple’s cruel treatment of Abasiama, which she sustains because to take a stand against it would rain down more abuse. Disciple begrudges Abasiama warmth for the upper floors which have insufficient heat to brace up against the cold Worcester, Massachusetts winter. This behavior of keeping the upper floors cold reflects Disciple’s abusiveness and penuriousness, not only with finances but with emotional intimacy and love.

Chiké Johnson, Patrice Johnson Chevannes in ‘runboyrun’ and ‘In Old Age,’ written by Mfoniso Udofia, directed by Loretta Greco, Awoye Timpo (Joan Marcus)

The division/cross section symbolizes a number of elements which define the characters so acutely portrayed by Johnson and Chevannes with maximum authenticity. It represents the compartmentalization of Abasiama’s and Disciple’s minds, especially Disciple’s as it relates to his unconscious memories which he’s suppressed, and on this night erupt with great ferocity. For Abasiama, she compartmentalizes her rage and anger against Disciple; to express the emotions will result in violence so she must be stoic. The events that play out from the past take place in the “basement” area. Events move upstairs when Abasiama extends grace to Disciple and he relives the flashback that has shaken his soul and increasingly knocked on his heart to be released as he has aged. If he does not, surely he will damage and destroy everything he has, most importantly his relationship with Abasiama.

It is in the “basement” of his being on this particular night that Disciple confronts the spirits that have haunted him for decades. By the play’s conclusion he revisits the blood soaked memories of his childhood during the horrors of the Biafran War. The spirits rise and their energy drives him to the brink of irrationality, which he takes out on Abasiama, who finally proclaims “enough,” and tells him she wants a divorce. In shock he returns downstairs and she hears him raving against the energies that roil him (his unconscious terror and guilt).

Adrianna Mitchell, Karl Green, ‘runboyrun,’ written by Mfoniso Udofia (Joan Marcus)

Mfoniso Udofia expertly weaves in concurrent flashbacks which reveal seminal events that shattered Disciple’s consciousness and emotionally freeze him in time. We learn why he is psychotic in recreated scenes of his family: sister (Adrianna Mitchell), mother (Zenzi Williams), Benjamin (Adesola Osakalumi). Karl Green portrays Disciple as a boy. And on Abasiama’s encouragement and love, he finally reaches the core event to expurgate it and grieve, thus beginning the healing process.

Chiké Johnson is acutely, sensitively invested in his portrayal of Disciple. Patrice Johnson Chevannes as Abasiama is expert and uplifting at the conclusion of runboyrun. And in the segue to the next play, we see her transformation into a withered, dried up old woman living with the rage and fury bestowed upon her by Disciple who has died by the opening of In Old Age.

Ron Canada, Patrice Johnson Chevannes in In Old Age, directed by Awoye Timpo, written by Mfoniso Udofia (Joan Marcus)

It is Abasiama’s fury that has carried over from her time with Disciple that Mfoniso Udofia examines in the play In Old Age. The stoicism we see in runboyrun blossoms into rage against herself for “putting up with” Disciple and not leaving him. Whether such anger manifests when we age, so that we have no tolerance for ourselves and are grumpy and angry with others is an interesting question that Mfoniso Udofia posits. Yet, it is in Abasiama’s interactions with Azell Abernathy the workman (Ron Canada), that the emotional abuse she never discussed or confronted Disciple about is now coming to call. And likewise, the tragic alcoholic-fueled abuse that centered around Abernathy’s marriage, that Abasiama intuits harmed his marriage, becomes a focal point of their interactions.

Abernathy and Abasiama clash and their expressed annoyances with each other are sometimes humorous. However, because they are both Christians, they attempt to bear up with one another. Indeed, Abernathy is much more determined to do so than initially Abasiama seems to want to. How Mfoniso Udofia brings these two together to establish the beginnings of a loving relationship is a lesson in grace and the spiritual need for forgiveness and emotional healing.

Ron Canada, Patrice Johnson Chevannes, ‘In Old Age,’ written by Mfoniso Udofia, directed by Awoye Timpo (Joan Marcus)

The plot development of In Old Age is simple. Azell Abernathy must persuade Abasiama to allow him to repair her house, the same house that she lived in with Disciple. However, the house is in more than need of repair. Abasiama hears what she believes is Disciple ranging and banging around in the basement. Just like in runboyrun when Disciple projected his terror and hurt onto Abasiama, now Abasiama projects her rage and anger onto the house and in magical realism fashion, it manifests in banging and noise.

One of the problems is that Abasiama subverted her own healing and empowerment to help Disciple redeem himself. Now she regrets her sacrifice and unselfishness. As a result, when Abasiama is forced to deal with Azell Abernathy (Ron Canada in a highly nuanced, sensitive, clarion performance), whom her daughters have paid to repair the house, the rage has so swelled inside of her she drips bile. Toward Abernathy, she is provocative and she riles him to the point where he nearly becomes abusive. However, he has learned. He leaves, goes outside and prays for her.

Ron Canada, Patrice Johnson Chevannes, In Old Age, written by Mfoniso Udofia, directed by Awoye Timpo (Joan Marcus)

His prayers work with power and change comes with revelation. Abasiama realizes she can no longer carry around past hurts and regrets. To expurgate them, she cleans out the “basement” (symbolic of her own soul and psyche), of all of the artifacts that Disciple kept there. As she throws them out, she frees herself realizing she is responsible for her own happiness and cannot blame her misery on Disciple. Cleansed from a night of dealing with her own regrets about her life, Abasiama is ready to face a new day. In a great, symbolic gesture, Abernathy washes her feet as Christ did with his disciples, showing he forgives her and forgives himself. It is an act of sublime strength. She receives his good will, Christian love and faith. She removes her shackles represented by her headdress and shows Abernathy her true self. She is beautiful. In their old age they have found love after confessing their faults to each other to be healed.

In Old Age is a hopeful, redemptive encomium to our ability to grow and regenerate our souls if we face ourselves. Directed by Awoye Timpo, In Old Age is just lovely and the complex performances by Canada and Chevannes are sterling, poignant and uplifting. Kudos to Andrew Boyce (scenic design), Karen Perry (costume design), Oona Curley (lighting design).

These are productions you do not want to miss for the profound beauty of Mfoniso Udofia’s work and the great ensemble acting. The tension in runboyrun is truly striking. runboyrun and In Old Age are at NYTW on 4th Street between 2nd and the Bowery. The production runs with one intermission. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

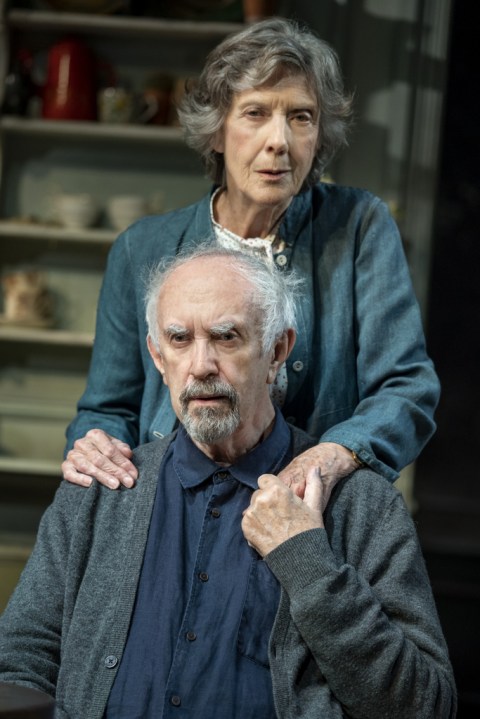

‘The Height of the Storm,’ Starring Jonathan Pryce, Eileen Atkins in Bravura Performances

Lucy Cohu, Eileen Atkins, Amanda Drew, Jonathan Pryce, Lisa O’Hare in ‘In the Height of the Storm, by Florian Zeller, translated by Christopher Hampton, directed by Jonathan Kent (Joan Marcus)

The Height of the Storm written by Florian Zeller (The Father, The Mother, The Son trilogy) translated by Christopher Hampton and directed by Jonathan Kent will be poignant for those who have family with Alzheimer’s or parents with advanced dementia. After seeing the play, my experience having relatives with these devastating conditions darkly reminded me of the MO of how such folks live in existential time. The divide between past and present, fabrication and fact are filtered through unconscious impulses that make memories rise to the surface of consciousness like dead fish subject to random currents. In the tangled mind of those with dementia, hallucinations prevail. Memory co-exists with scenes in “present” time and all remains fluid, colored by the perceptions of the moment in whatever moment it is.

Living under such confusion remains frustrating for the sufferer and family who must bear up against the onslaught of alternating states of consciousness and melding realities. Family members sustain the disease. Forced to be complicit with the fantastical consciousness exhibited by their afflicted parent, they choose not to upset them with the facts of current time, place and circumstance which would be pointless. The afflicted wouldn’t accept what they say anyway, convinced of the truth of where they are, lost in their dreamscape of past perceptions. It is a cruel joke to try to make sense of the nonsensical.

Eileen Atkins, ‘In the Height of the Storm,’ directed by Jonathan Kent, written by Florian Zeller, translated by by Christopher Hampton (Joan Marcus)

And so it goes for the characters in Zeller’s The Height of the Storm which elucidates a marriage between André and Madeleine that has lasted amidst triumphs and conflicts for fifty years. And so it goes for the audience who arbitrates the “reality” in present time of what it experiences during the interactions of family members (André, Madeleine, Anne, Élise) though clouds of glorious time past intervene. And sometimes the clouds work themselves into a storm, the memory of which repeats and repeats in their conversation.

In this play the fog, confusion, the displacement of time present with time past are acutely manifested by writer André (Jonathan Pryce in a portrayal that is a tour de force) though the entire family manifests elements of the same as they relate to him and each other. Madeleine played with astounding, measured brightness by Eileen Atkins is André’s stoic, vibrant, organized, take-charge wife who floats in and out of his stream-of-consciousness as he fades in and out of her conversations with her daughters.

Jonathan Pryce, ‘In the Height of the Storm,’ directed by Jonathan Kent, written by Florian Zeller, translated by by Christopher Hampton (Joan Marcus)

Zeller also focused on dementia in another of his plays, The Father (2016, The Samuel J. Friedman Theatre) starring Frank Langella who won a Tony Award for his performance. In The Father, another iteration of André must deal with the vicissitudes of memory loss, confusion, and his psychological responses of anger to that which is uncontrollable, his disease. Without the mitigating influence of his wife, André and his two daughters Élise and Anne must confront his worsening condition. The arc of development is explicit; we “get it.” We empathize and find catharsis in the tragedy of a family impacted by the mental disintegration of the patriarch. In The Father Zeller wraps up the characters, development and themes neatly; we are grateful, move on and generally forget what we’ve witnessed.

There is no such easiness in The Height of the Storm which is unforgettable because it is elliptical, abstruse and annoyingly so until we understand Zeller’s themes and the core of where he is driving this work. There is no clear arc of development in chronological story-telling. Time is defined by memory and that is the present consciousness. The amorphous, vague threads of conversation are filled with details chucked into the dialogue as we watch the daughters, Anne (Amanda Drew), Élise (Lisa O’Hare) father (André) and mother (Madeleine) interact, slip in and out of present and past moments, watch each other, are silent listeners. The moment we think we understand the concrete facts, for example that André won’t talk to Anne initially because he is caught up in a foggy Alzheimer’s reverie looking out the window, the axis of the scene shifts and he speaks to her and ends the interlude spouting, “Toll the bell, toll the bell. For all of you. Oblivion to the living!”

Jonathan Pryce, ‘In the Height of the Storm,’ directed by Jonathan Kent, written by Florian Zeller, translated by by Christopher Hampton (Joan Marcus)

This is a pronouncement that seems incredibly profound. And though we may admit it to ourselves or not, we face an oblivion of belief. We presume we understand what is happening around us in our lives, but it is our own perception, what we choose to believe about aspects of reality. We have no way of proving we are right or wrong. That is a form of oblivion whether we accept it or not. Similarly, as the characters in the play progress with each other, we watch/soldier on attempting to grab hold of and make sense of the interactions of the family. Moments of wisdom fade. And another curious scene of convolution ensues.

Zeller’s work is replete with axis shifts that create staggering imbalances so we are confounded about what is happening because we are not grounded in time. That it appears to be mid morning in a stately Victorian kitchen with a study nook, hallway lined with bookshelves, a kitchen window overlooking a garden doesn’t help. Precisely when the events occurred and in what sequence remains opaque. This is one morning of one or two mornings in the consciousness of André and Madeleine and their grown daughters who visit at vital times. Then it appears the mornings meld together without particularity except for tidbits of “apparent” distinguishing details in conversation.

Eileen Atkins, Jonathan Pryce in ‘In the Height of the Storm,’ directed by Jonathan Kent, written by Florian Zeller, translated by by Christopher Hampton (Joan Marcus)

After Anne and André discuss the problem of his living alone in the house by himself, the scene subtly shifts and the atmosphere brightens with the truth or appearance of reality. The efficient, solid-state Madeleine comes in from shopping and lightly humors André. Is this present reality unfolding or someone’s memory from time past? Surely, this scene happened at some point in their lives. But when? We must sustain our confusion as uncomfortable as it is. But not for long because Zeller is constantly upending our former perceptions and muddling our attempt to make meaning. We experience André’s addled mind at work navigating the sea of confusion that is representative of those with dementia. And yet, we also experience Madeleine’s grounded, fact-based consciousness in alternate scenes after atmosphere shifts that randomly intrude, governed by a family member’s comment that joggles a memory and changes the mood once more from lightness to the austere and portentous.

Flowers arrive signifying someone has died. Who? It can’t be the characters present. As Madeleine and her daughters have a conversation about André in the past tense as he sits quietly in the chair, our certainty grows that he has died, physically, surely mentally. Then Zeller shifts the axis once more and in the next moments, André comes to life and he and Madeleine talk about what she is cooking (mushrooms). This subject brings up additional free associations from the past, i.e. André’s walks to look for mushrooms until he stopped when he heard another gentleman did the same and fell into the river and “died.” But we find out from André in another scene, that this man’s death was faked when André sees him years later with a woman. It is one more detail which we cannot deem with certainty is either credible or fictional or twisted threads of both.

Eileen Atkins, Jonathan Pryce in ‘In the Height of the Storm,’ directed by Jonathan Kent, written by Florian Zeller, translated by by Christopher Hampton (Joan Marcus)

With such convolutions in the characters’ conversations, Zeller demonstrates the randomness of consciousness, reality and memory. With each uncertainty prevails. In the scenes that follow, it appears that Madeleine has died as his daughters decide what to do with André, who for his part, is contented to stay in the gorgeous house and particularly the kitchen where he appears most comfortable remembering his lunches with Madeleine cooking mushrooms.

Zeller plays with our suppositions like a magician. He makes it untenable for us to choose what to assume is happening. In this we become like André and unlike Madeleine who remains assured, nonplussed and forward moving. An important theme Zeller emphasizes is that the nature of perception, choices, undercurrents that propel memories into the foreground may be wholly unreliable to begin with. If we are unlucky to have dementia, such expurgations from the unconscious force us to live in the memory we’ve edited as reality without the barriers of time. But that may not be so unlucky, after all. It is the epitome of existentialism, of living in the moment, whatever the moment is, whenever it comes, erupts, departs, until another “moment” arrives.

As a result themes of uncertainty of what consciousness is are reflected in each of the characterizations in the play. We cannot identity who has died, what the time line is, when the storm came and whether the scenes are the characters transformative memories or reflections of André‘s thoughts in his besieged mind which may not be as addled as we assume. An attempt to make sense of the “say what?” without outside evidence to understand whether André or Madeleine or both have died remains futile. Regardless, whichever parent has fled or will flee the planet first, the other is or will be left to deal with the memories, consequences and aftermath- for the daughters’ upset or consternation at the loss of a partner. Or something else. It appears that Madeleine is able to cope better than André whose lifeblood is Madeleine. However, that, too, is equivocal.

Eileen Atkins, Jonathan Pryce in ‘In the Height of the Storm,’ directed by Jonathan Kent, written by Florian Zeller, translated by by Christopher Hampton (Joan Marcus)

Finally, in the last scene, the daughters leave with all of their obstructions. The couple have the house and memories to themselves. It is a scene of pure consciousness with humor and heartbreak. Only then do we comfortably settle on the determination that when all was said and done, considering André‘s affairs, personality difficulties, and Madeleine’s wifely stoicism and love for her husband, their marriage was a fairly good one and they are together. Of course, Madeleine gets the credit for the unity of their marriage which André acknowledges. But for all our comfort, we may be witnessing the conversation of two ethereal beings in present consciousness, a sardonic irony that Zeller teases us with. Interestingly, with all of our assumptions about who dies first, after that storm, consciousness continues, a resurrection. And the unity the couple established and now share remains uplifted forever.

It seems that one of Zeller’s intents for the play as a series of reflections and vital vignettes that have little arc of development, is to place us in a consternation of misshapen realities that keep us off balance and frustrated until we relax. Such is the haphazard upside down world of those with dementia and those who must negotiate another’s dementia. But the theme also arises that those who live in their beliefs and certainties are not unlike the Alzheimer’s patient. They too may live in a fog of past memories, dreaming up what never happened, only they don’t know it. For both the ill and not so ill, Zeller affirms that glimpses of reality are fleeting; the past or future dominates. Living in the moment is a rarity. But if one is fortunate as both characters are at the play’s conclusion, one lives in a state of agreement and contentment “when the kids have gone.”

Jonathan Pryce and Eileen Atkins make this dense work sing and vibrate it into life, infusing their characters with truth and authenticity. Kudos to the creative team: Anthony Ward (scenic & costume design) Hugh Vanstone (lighting design) Paul Groothuis (sound design) Gary Yershon (original music).

The Height of the Storm runs with no intermission at Manhattan Theatre Club’s Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, 261 West 47th Street. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

.

Bernard Shaw’s ‘Caesar & Cleopatra,’ Starring Robert Cuccioli and Teresa Avia Lim

Robert Cuccioli and Teresa Avia Lim in Bernard Shaw’s Caesar & Cleopatra, directed by David Staller at Theatre Row (Carol Rosegg)

The Gingold Theatrical Group noted for its Shaw productions is presenting Caesar & Cleopatra directed by David Staller at Theatre Row. The production is a tightly crafted, well-acted revelation of the historic and intriguing relationship as Shaw conceives may have unfolded between Cleopatra and Caesar. Having thoroughly researched their history to examine both their humanity and extraordinary genius, with economy, Shaw reveals individuals worthy of his depiction in interest, humor and vitality.

Robert Cuccioli and Teresa Avia Lim in Bernard Shaw’s Caesar & Cleopatra, directed by David Staller at Theatre Row (Carol Rosegg)

The production shepherded by Staller winningly presents the dynamic relationship between Caesar and Cleopatra which engages us with Shaw’s novel/fictional approach toward these icons as he generally follows historical events. The Gingold Theatrical Group has slimmed down Shaw’s version keeping the most salient scenes and consolidating characters providing narration by Ftatateeta (Brenda Braxton in a powerful performance) at the beginning of the production and throughout to fast-forward events and comment on their sequence with poetic persuasion.

Brenda Braxton, Teresa Avia Lim, Robert Cuccioli in Bernard Shaw’s Caesar & Cleopatra’ directed by David Staller (Carol Rosegg)

Caesar is portrayed by Robert Cuccioli whose presence and manner is believably confident, relaxed and princely even after the exhaustion of having just led his troops to conquer the Egyptians. However, knowing anything about Caesar before Shaw’s revelations at this point in the leader’s life, one realizes his personage that was incredible in stature and nobility was acquired over time. His popularity as a leader was grounded upon his military experience and wisdom bringing success to Rome in extending the Roman Empire. Cuccioli acutely engages as he renders this portrait of a man who doesn’t believe himself past his prime. As Shaw has drawn him and as Cuccioli so aptly portrays him, he sports humor, is playful yet has the perspicacity to note that the vivacious, lively teenage girl at the feet of the Sphinx must be Cleopatra, though he twits her about it after he realizes who she is.

(L to R) Teresa Avia Lim, Robert Cuccioli, Rajesh Bose in Bernard Shaw’s ‘Caesar & Cleopatra,’ directed by David Staller (Carol Rosegg)