Category Archives: NYC Theater Reviews

Broadway,

‘The Shark is Broken’ Three Men Missing a Shark, Broadway Review

Much of the real terror related to the film Jaws (1975), was experienced behind the scenes. The film was over budget $2 million and its flawed premise needed correction because the star of the picture, Bruce (the monster great white shark), was unworkable. To add insult to injury, director Steven Spielberg and the main cast were unproven at the box office and had issues to overcome. Finally, there was no finished script. For all intents and purposes, the film looked to go belly up, just like the three versions of mechanical Bruce, who foundered, sputtered and sank forcing the director and writer John Milieus into extensive rewrites.

However, Hollywood is the land of miracles. Jaws (adapted from Peter Benchley’s titular novel), broke all box office records for the time, despite the frankenfish never really “getting off the ground” the way Spielberg intended.

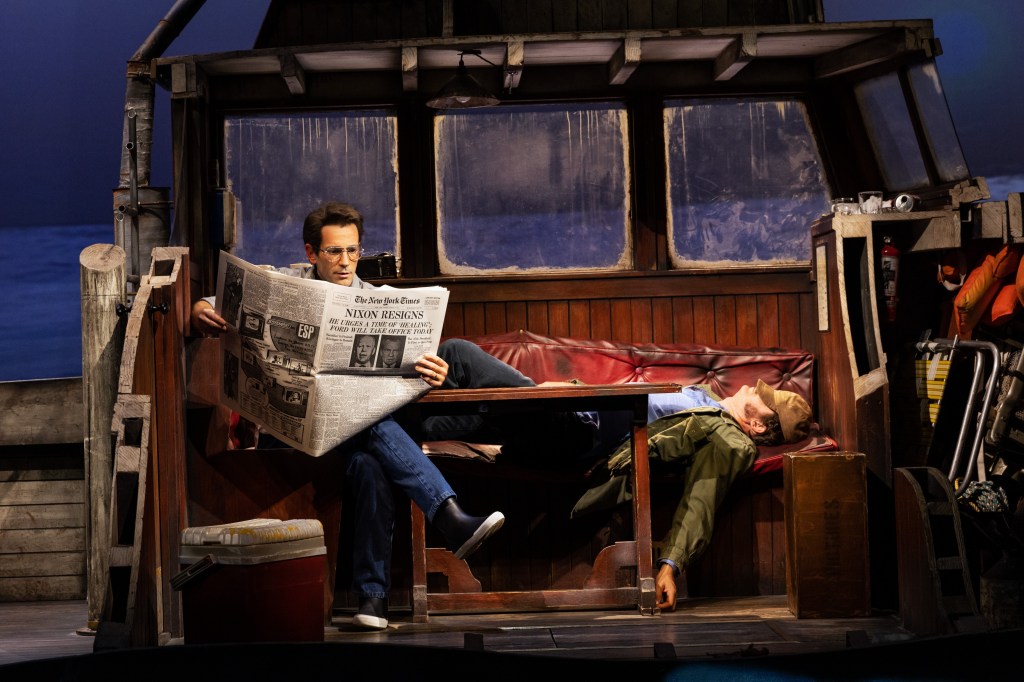

The Broadway show The Shark is Broken, currently sailing at the Golden Theatre until the 19th of November is the story of the three consummate actors behind the flop that might have been Jaws if Spielberg and his team didn’t rethink their broken monster, proving less screen time is more powerful when the shark finally shows up. The amusing play co-written by Ian Shaw (Robert Shaw’s son) and Joseph Nixon, and directed by Guy Masterson comes in at a slim 90 minutes. It features Alex Brightman (Beetlejuice the Musical) as Richard Dreyfuss, Colin Donnell (Almost Famous at The Old Globe) as Roy Scheider, and Ian Shaw (War Horse), who plays his father Robert Shaw.

The play focuses on these three actors who attempt to deal with the circumstances and each other as they try to make it through the tedious days waiting for Bruce, the real star, to “get his act together.” However, Bruce never does. Indeed, if one revisits the film, one must give praise to the superb performances of Dreyfuss, Scheider and Shaw who make the audience believe the shark is horrifically real and not a broken-down, mechanical “has been.”

Crucial to the film’s success are the dynamics among the actors which The Shark is Broken highlights with sardonic humor and a legendary sheen. Once the film skyrocketed to blockbuster status, the high-stress problems surrounding the film’s creation could be acknowledged with gallows humor. Such is the stuff that Ian Shaw and Joseph Nixon configure as they reveal intimate portraits of the actors’ personalities, foibles, desperations and bonding, while waiting for their “close-ups” with Bruce. Though the play appears “talky,” the tensions and undercurrents form the substance of what drives the actors. Like a shark that glides with fin above water, what lies inside each of the actors threatens to explode when least expected.

Even seemingly mild-mannered, emotionally tailored Scheider flips out. When his luxurious sun bathing is curtailed and his presence demanded on set, Donnell takes a bat and smashes it on the deck in fury. Donnell has no dialogue but his actions and body speak louder than words and we see how underneath that calm demeanor, Scheider is capable of potential violence which he keeps on a leash and, like a dog, gets it to heel when he wishes.

Based on Robert Shaw’s drinking diary, family archives, interviews and other Jaws‘ sources, Shaw and Nixon pen an encomium to the actors’ efforts and relationships forged during their claustrophobic time spent on the Orca, which floated on the open ocean east of Martha’s Vineyard between East Chop and Oak Bluffs. As the actor-characters arrive, we note the resemblances to their counterparts, further emphasized by their outfits, (costumes by Duncan Henderson), speech (dialect coach-Kate Wilson), and mannerisms.

Donnell is the fit, tanned, attractive, temperate Scheider, well cast to portray police chief Brody, head of the shark expedition. Brightman is the pudgy, scruffy, angst-filled Dreyfuss, who sounds and looks like the actor, and is filled with brio and insecurity as Ian’s Shaw batters his ego. As a dead-ringer, Ian portrays his father Robert Shaw, who merges the steely-eyed, gravely voiced, hard-drinking Quint with himself so the boundary between actor and character is seamless. Ian’s Shaw is comfortable in his cap and jacket ready to conquer his prey which includes the poorly written Indianapolis speech, and Richard Dreyfuss.

Thanks to the creative team, Duncan Henderson’s set and costume design, Campbell Young Associates wig design and construction, Jon Clark’s lighting design, Adam Cork’s sound design and original music, and Nina Dunn for Pixellux’s video design, the scenes when the three are on the Orca waiting for the great white to arrive include the manifested cross section of the boat interior, undulating ocean with seagulls flying overhead, wave washing sound effects, sunsets, and a lightening storm during which Ian’s Shaw stands rocking near the boat railing as he challenges the storm. The designated force of Robert Shaw comes through particularly, as he stands arms outstretched, back to the audience, accepting whatever the chaotic, dangerous elements unleash on him.

What do these men do to redeem the time as they wait for one of the three versions of Bruce to be commissioned to work? They do what sailors have done time immemorial: play innumerable card games, read the newspaper, play pub games and verbally and physically attack each other parlaying wit, wisdom, insults and choking. The latter occurs when Brightman’s Dreyfuss calls Shaw’s bluff about giving up drinking. With a quick maneuver, Dreyfuss takes Shaw’s bottle and tosses it over the side, a severe cruelty for a drinking man. Ian’s Shaw leaps into ferocity. It is only Scheider’s peacemaking and his threat that Shaw will be sued for delaying the film further, that remove Shaw’s ham hands from Dreyfuss’ quivering throat.

The feud between Dreyfuss and Shaw is exacerbated by inaction and the actors’ boredom between scene takes. This gives rise to the competitive hate/love emotions between the two men, which escalate during the play and are a fount of scathing, sardonic humor. When confronted about it, Shaw insists he is helping to improve Dreyfuss’ performance, and indeed, the tension between the actors behind the scenes travels well to their portrayals on film. The thrust and parrying of epithets and wit, which Scheider attempts to mitigate to no avail, forms the backbone of the dialogue which comes at the expense of Dreyfuss’ savaged ego.

Shaw, a noted writer and giant on the stage, sharpens his wordplay on Dreyfuss’ attempts at rebuttal. It is only after a quiet moment between Scheider and Shaw when Scheider tells Shaw how much Dreyfuss admires him, that Shaw lets up, but only a bit.

Son Ian is not shy about his father’s alcoholism and he plays the role as if he was familiar with how crusty and gritty his father could get when he was “three sheets to the wind.” Though he lost him at a young age and most probably doesn’t remember him all that well, the point is made that alcoholism and loss is generational. Robert Shaw shares that he lost his father to suicide when he was a youngster and always rued that he could never assure his dad that things would be all right. By that point his father had killed himself. Robert Shaw also died young and left his nine children wanting him. Thus, homage is paid by Ian to his grandfather and father who both battled alcoholism and died before their sons could really know them.

At its most revelatory, The Shark is Broken is about fathers and sons and how their father’s abandonment and/or rejection traumatized the actors who struggle to get out from under the sense of loss, rejection and insecurity. Dreyfuss shares that his father left the family and wanted him to be a doctor or lawyer. Scheider reveals his father disdained his acting career, until he eventually accepted it and became proud of his son. It is the few shared moments like these where the men bond and find common ground that are strongest and wonderfully acted. The play might have used more of these moments and fewer attempts at ironic jokes about how Jaws won’t be memorable in film history.

Shaw’s reductio ad absurdum of the future of films as a measure of sequels: sequels will beget sequels of sequels that have sequels rings true, of course. But the statement for humorous purposes is far from prescient.

The Shark is Broken premiered in Brighton, England, went to a 2019 Edinburgh Festival Fringe run then opened on the West End before it arrived on Broadway. The play is humorous and entertaining with some missed opportunities for quiet, soulful moments. Certainly, those who have seen Jaws and its sequels will have fun and enjoy the near replica of the Orca and its inhabitants for a captured moment in film history made alive. The acting is crackerjack and Ian’s interpretation of the Indianapolis speech, which Shaw wrote himself, is at the heart of the film. As Ian delivers it, it is at the heart of the play and symbolically profound.

The Shark is Broken runs without an intermission at the Golden Theatre (252 West 45th Street). For tickets and times, go to their website https://thesharkisbroken.com/

‘The Half-God of Rainfall’ at NYTW, Review

Inua Ellam’s epic poem The Half-God of Rainfall, has been brought to life with theatrical grist at New York Theater Workshop. Currently running until 20th August, the reconfiguration of Greek, Yoruba archetypes and myths are merged against a modern backdrop of an Olympic basketball champion born of mixed raced parents, a simple Nigerian woman Modúpé (Jennifer Mogbock) and the Greek god of thunder Zeus (Michael Laurence).

Their fantastic progeny is the half-god Demi (Mister Fitzgerald). It is his exploits and the overthrowing of the patriarchy which the actors narrate, illustrate, move through and reimagine during the 90 minute spectacle of sight, sound and movement that is strongest and most exhilarating during the last 15 minutes of production.

Ellam’s poem is ambitious as is director Taibi Magar’s vision for The Half-God of Rainfall’s breadth and scope. Interestingly, the very nature of the foundational myths of the Western world vs. African folklore and tradition collide like tectonic plates during an earthquake. Thus, when god of thunder Sango (Jason Bowen) loses the competitive race against Michael Laurence’s Zeus and must yield his finest prize Jennifer Mogbock’s Modúpé, Zeus’ rape and the birth of their son Demi is symbolic of the traditions of war between conquerors and their conquered. Rape was and still is a subduing weapon of war, legitimized as acceptable spoils of conquest.

Without a father, raised by his mother, Demi is typically disadvantaged and rejected by his peers, despite his apparent supernatural gifts as a demigod. Eventually, as a Marvelesque hero of stature and statuesque build, Demi receives the fullness of his powers and becomes a basketball great on the Golden State Warriors team. There, he learns about other demigods whose talents suppressed in their natural lives shine in competition as his do.

However, his greatness eventually becomes known to his father Zeus, whose machismo and fiercely tyrannical spirit compels him to confront his son. Will Demi be able to schmooze his father and encourage him to receive his son with paternalistic pride? Or will another result occur where he overthrows the oppressor culture and vaunts his mother’s African traditions? Which identity will Demi embrace and will he be able to meld the two and tease out the best in both mythic and cultural traditions? These themes and conundrums are answered by the conclusion.

As the poem/dramatization progresses, the other deities contribute to chronicling the high points of Demi’s story. These gods include Zeus’ wife Hera (Kelley Curran), Elegba (Lizan Mitchell), and Osún (Patrice Johnson Chevannes). Peppered throughout with philosophical wisdom and historical reference points of Greek and Western colonial oppression, the dramatized poem emphasizes that the conquerors treat their subjects with opprobrium, alienation and objectification. Additionally, the deities reveal that like rape, cultural assimilation is a weapon of war. Diluting the cultural artifacts, language and human traits of a race are the ultimate form of conquest and annihilation.

Ellams’s poetry is both rhythmic and expositional. The actors hone a fine sense of the poetic beats in each segment bringing the meaning into focus. Their storytelling is elucidated by Riccardo Hernandez’ scenic design, Stacey Derosier’s lighting design, Mikaal Sulaiman’s sound design and Tal Yarden’s projection design. The actors don Linda Cho’s costumes as a part of the action comfortably aligning themselves with their various roles as they move in and out of their characters seamlessly.

Beatrice Capote’s Orisha movement and choreography flows and indeed could have been incorporated much more, especially during the characters’ presentational narratives. Likewise, Orlando Pabotoy’s movement direction might have been integrated more to enhance the spoken-word which the actors direct to the audience as they tell Demi’s story.

Striking are the immersive elements, of creative design, for example the use of shimmering blue cloth which the actors use to effect undulating water. The beautiful projections suggest the majesty of the cosmos the gods inhabit. Other multi-hued projections reflect both the ethereal and the manifest world of the earth which Demi attempts to inhabit and conquer in his own right. Likewise, the falling rain is a palpable effect to ground us in this realistic yet stylized piece where the director elicits how phantasms are present in the reality we see, and think we know, but do not.

Overall, the actors effect emotional intensity especially at the conclusion. Because there are fewer scenes of interaction between the characters, one wonders if the first half of the production might have benefited with more movement and character dynamic rather than the actors’ direct addresses to the audience.

However, Magar brings the events to a satisfying conclusion as Mogbock’s Modúpé vindicates her own humanity and the cultural, historic, African traditions bringing release and redemption. The finish is as startling as the heartfelt events that prompt Mogbock’s Modúpé’s final, relentless actions.

The actors and creative team have generated a unique experience so that Ellams’ epic narrative leaps off the page and into one’s imagination with their fine stagecraft. For tickets and times go to the NYTW website https://www.nytw.org/show/the-half-god-of-rainfall/

‘Here Lies Love,’ The Stunning Bio-Pop-Musical Sounds Alarms About the Price of Democracy

The Millennium Club is the phenomenal, multi-level, theatrical setting of the bio-pop musical Here Lies Love. The resulting panorama is a monolith of disco and pop music, many-hued neon lights, black and white historical film clips, multiple dazzling screen projections, and spot-on performers’ heightened song and dance moves “here, there, everywhere” in living color. With 12 musicians (guitar, percussion, bass, etc.) some of the musical backing is prerecorded like karaoke, a cultural staple in Filipino lives. All this is the backdrop to David Byrne and Fatboy Slim’s spectacular immersive, sensorial, orgiac experience currently at the Broadway Theatre.

At the unfolding of the alluring dance party, the political and social history of 20th century democracy in the Philippines coalesce under a gleaming, disco ball. On the dance floor the pink, jump suited ushers shepherd and move the audience around a platform in the shape of a cross (a coincidental reference to the predominately Catholic country) that in a different configuration later becomes the bier upon which the coffin of the assassinated Ninoy Aquino moves leading the audience in the funeral procession.

On the second level, the jazzy, sun glass-wearing, cool, black-leather outfitted DJ (Moses Villarama) amps up the crowd, encouraging their investment in the show’s diversions. Throughout, the audience members in the balconies on three sides and on the first level dance floor, cheer, mourn, laugh and applaud. Their interactive roles as the captivated conspirator/citizens allow them to witness and participate in the iconic rise and fall of Ferdinand (Jose LLana) and Imelda (Arielle Jacobs) Marcos, celebrity leaders turned dictators.

With American encouragement and influence steeped in an autocratic colonial past, the Marcoses’ initially inspired governance devolved into a brutal, self-serving regime. Peacefully overthrown by the People’s Revolution (1986), after years of repressive, murderous authoritarianism, the Marcoses’ story masterfully stenciled by Byrne, Slim, Clint Ramos’ research and Alex Timber’s enlightened direction, is an important work for us in our time of QAnon, Donald Trump, the Federalist Society’s purchase of Supreme Court Justices, the Dobbs’ Decision and foreign donor’s dark money purchasing politicians, who, to feather their own agendas and dilute and destroy global democracies and the right of the people to self-governance.

The narrative of Here Lies Love is an encomium in song and dance. In its Broadway premiere ten years after its off-Broadway premiere at the Public (2013), the musical features Filipino producers and is brilliantly performed by an all-Filipino cast. With passion they portray the narcissistic Marcoses and their acolytes, who conspired to gradually hoodwink citizens to dance to the Marcoses’ siren songs.

Importantly, the production highlights the heroes. It is their vision for the Filipino people, and their hopes for a democratic country, that inspired them to risk their lives for the Filipinos’ right to “a place in the sun.” These courageous exposed and railed against the Marcoses’ excessive squandering of millions of dollars in a luxurious lifestyle, while a majority of deprived citizens had insufficient access to life-sustaining food, shelter, clean water and the freedom from military terror. This is the story of their love, and the sacrifice of their lives in the revelation of how easily leaders may fall prey to their own crass weaknesses and destroy a nation they disingenuously proclaim to love.

Key among the heroes is the liberal leader of the opposition party, Ninoy Aquino (Conrad Ricamora in an inspired and dynamic portrayal), and those aligned with Aquino like his mother Aurora Aquino (the wonderful Lea Salonga). Aquino’s persistent example, assassination by the Marcoses who were never held accountable, and subsequent martyrdom paved the way for the People’s Revolution.

Though the Marcoses are key players in the musical, Byrne and Slim make sure through quotes and commentary from interviews and news reports that praise does not go to the despots, one of whom is still attempting to exert power today through her son and president of the country. Here Lies Love is an object lesson in vanity, dereliction of duty, self-deception and treachery which Fatboy Slim and Byrne spin with irony in their lyrics in the title song, “Here Lies Love,” and in Imelda’s concluding song, “Why Don’t You Love Me?” written by Byrne and Tom Gandey.

Though the title of this production belies Imelda Marcos’ “love” for her country (she affirms her epitaph should read “here lies love”) Byrne, Fatboy Slim and director Alex Timbers underscore the hypocrisy of her love revealed in the musical’s arc of development. Her hypocrisy and velvet insidiousness are especially demonstrated in the 3,200 Filipinos killed, 30,000 tortured and disappeared and 70,000 imprisoned (the numbers are higher most probably).

These statistics are listed in the surrounding projections in black and white. The musical uplifts the Filipino people’s resilience, courage and love of their countrymen and women. The citizens are a shining example for democracies around the world and for whom the musical’s title really applies. Indeed, the Filipinos’ love is demonstrated in the People’s Revolution at the conclusion, and culminates memorably in the final poignant song.

The production is majestic and profound. Its themes counsel that citizens of democracies must be sentinels against those like the Marcoses, who would exploit democratic elections, usurp power, declare martial law, and order the military to protect the powers of the executive, while disbanding all the other branches of government. By silencing their critics and killing opponents, dictators like the Marcoses rebrand terrorism as law enforcement in order to steal from the treasury and maintain their hold on power. This follows after smearing the opposition, jailing perceived enemies without due process, nullifying democratic laws and wiping out a free and fair press, who cannot call out their crimes.

All of these egregious actions Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos did while the United States turned its head and looked away.

Thus, as the audience dances and follows the guidance of the ushers and DJ, they are initially blinded and mesmerized by the fantastic surreality of beauty, fun and energy. And as Imelda the beauty queen ends her relationship to Nimoy Aquino and takes up with Ferdinand on a publicized 11 day whirlwind romance that ends in a white wedding, we watch as she morphs from the naive country girl to the savvy doyen of American fashion and celebrity. The “steel butterfly” (a nickname given to her by the press), has become a clever political animal, who is a help meet to ruthless Ferdinand right before our eyes.

The 90 minute dance party summarizes the Filipino seduction and decades of growing repression in key events. After their marriage, Imelda is overwhelmed by being in the limelight and has a nervous breakdown, requiring therapy and becoming addicted to drugs. Jacobs portrays the changes in Imelda convincingly. When she sings “Walk Like a Woman,” we realize that the once innocent girl has become a seductively calculating political creature as she tirelessly campaigns with her husband and helps him win the presidency. She becomes knowledgeable about culture and obsessed with the construction of buildings (The Philippine Cultural Center), which draw attention to herself as a celebrity but do nothing for Filipino citizens.

The projections and black and white film clips from archives are salient in revealing the glittering Marcoses rise. Byrne’s lyrics are from interview quotes and reports covering the Marcoses and Aquino. Photographs show Imelda with everyone from Andy Warhol to various leaders like Ford and later Reagan,, who propped up the Marcoses and gave them sanctuary in Hawaii after they fled during the People’s Revolution. Ricamora’s Aquino gives rousing speeches about Imelda’s egregious use of funds for a cultural center (“The Fabulous One/I’m a Rise Up”) which sets the audience/citizens on edge and alerts them to financial corruption in the Marcos’ regime every time Aquino calls them out. Byrne creates lyrics that borrow heavily from his speeches.

The turning point comes after Marcos’ scandal with American actress Dovie Beams, whose impact on Imelda is ironically highlighted in a dance number with multiple “Dovie Beams” in black bikinis and blonde wigs. The original tape recording between Beams and Marcos is played during this point in the production accompanied by music and lights reinforcing the spectacle. Imelda considers that “Men Will Do Anything” (Jasmine Forsberg is Imelda’s powerful inner voice).

Losing trust in Ferdinand, she conveniently latches onto self-deception and sings of her dream that she is the people’s star and slave (“Your Star & Slave”). As she disingenuously commits herself to her country, Ferdinand, licking his wounds in embarrassment, retires to the hospital with Lupus and attempts to win Imelda back. Jacobs and Llana’s duet “Poor Me,” is a beautiful example of a couple lying to each other, complicit in keeping their hold on power.

The beating of students protesting the Marcoses’ corruptions, Estrella’s (the heartfelt Melody Butiu) revelations of Imelda’s lies about her heritage (“Solano Avenue”) and Estrella’s subsequent arrest and punishment for going to the press, puts the Marcoses’ maladministration on everyone’s radar. Aquino speaks for the masses in his criticism of Imelda, which she and Ferdinand not only ignore, but feel victimized by. The easy way dictators shift blame and beat their breasts about being persecuted is highlighted by Byrne’s song and incredibly acted by Llana and Jacobs. One almost believes they are victims and the unjust criticism is weaponized by Aquino, protesting students and opponents.

After bombs go off in Miranda Plaza wiping out almost all the liberal party, Marcos blames it on the liberals (1984 fascist logic-why would they intentionally kill themselves) and declares martial law in Order 1081. Byrne and Fatboy Slim have outdone themselves in the lyrics and forceful, pounding music that codifies the new dictatorship and power grab by the Marcoses. During the performance of “Order 1081,” the statistics enumerate the casualties of the Marcoses’ punishments for for protests. Ninoy Aquino is jailed for 7 years. There are no trials, just guilt and oppression. The staging and performances are shocking and disturbing.

We ask, what? Are the glorious Marcoses murderers? Indeed. And they act privileged and justified in brooking all “nefarious” opposition.

After seven years when the jailed Aquino needs a heart operation, the Marcoses send him and his family to America on the stipulation that he never return. Aquino doesn’t keep his promise to the criminal dictators. Instead, he sacrifices his life, an assassinated martyr, which is another shocking blow in the musical slammed into the audience’s psyche with all the force of lights, sound effects and music that explode when the audience least expects it. And in the aftermath with Salonga’s song as Aquino’s mother, the crowds at his funeral effected by the ushers and the coffin on the platform are staged with impeccable emotional poignance.

Timbers reveals how the Peaceful Revolution happens in the staging and the surrounding projections. We understand that the crowds demand Marcos’ resignation after a rigged election in which he proclaimed himself the winner. The people’s massive protests demand the Marcoses resign. Ronald Reagan gives his friends sanctuary in Hawaii, announced via projections of New York Times’ headlines. It’s an appalling closure to the Reagan administration’s supporting dictators and murderers who deny culpability.

Ironically, in the musical it’s a blip that passes speedily which Byrne intentions because he is sardonically indicting the Americans for supporting dictators as a horror of colonialism’s aftereffects. Also, it is incredibly current and an expose of the Republican MO to protect their own. They conveniently pardoned Nixon’s criminality during Watergate and refuse to censure or disqualify Donald Trump as a presidential candidate indicted for his crimes against the country.

The last song “God Draw’s Straight” (But With Crooked Lines) is a testament that democracy depends upon the power of the citizens worthy to govern themselves. The song is magnificent, encouraging and a reminder that citizens must actively resist the lies, excesses and dereliction of corrupt, dangerous leaders, by continually calling them down in peaceful protests.

From the top of the dance party whose song “American Troglodyte” incriminates the Marcoses’ chief influencer, the crass, monopolistic, corporate consumerism of America, to “God Draw’s Straight” (But With Crooked Lines), this gobsmacking production chronicles how the Marcoses, emblematic of how dictator-murderers, subvert democracies and rise themselves up through lies, misinformation, disinformation, propaganda, self-victimization and the vitiation of constitutional government in exchange for military oppression and terrorism. Of course, the dictators justify their crimes with the “poor me” ploy, the refusal to admit responsibility and martial law directed to empower and protect them.

Every American citizen should see this incredible work of art whose creative team worked overtime to meld all the technologies and elements to effect Timbers,’ Byrne, and Slim’s (with additional music by Tom Gandey & Jose Luis Pardo) vision. The performers are incredible, invested, determined to express this vital story that must be told.

Special recognition goes to Annie-B Parson’s choreography, Clint Ramos versatile and quick change costume design (referencing the times according to news articles and video clips), Justin Townsend’s lighting design, M.L. Dogg & Cody Spencer’s well-balanced sound design (not any easy feat with such a venue), Peter Nigrini’s wonderful projection design, Craig Franklin Miller’s spot-on hair design and Suki Tsujimoto’s make-up design. Additional kudos goes to J. Oconer Navarro (music director), Kimberly Grigsby and Justin Levine (vocal arrangement), Matt Stine and Justin Levine (music production & additional arrangements).

I’ve said enough. For tickets and times go to their website https://www.telecharge.com/Broadway/Here-Lies-Love/Ticket

Photos by Billy Bustamante, Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman (2023)

‘Hamlet,’ Kenny Leon’s Dynamite Version, Free Shakespeare in the Park

There are more iterations of Hamlet presented globally in the last fifty years than are “dreamt of in your philosophy.” To that point director Kenny Leon’s version of Hamlet, currently at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park until August 6th, provides an intriguing update of the son for whom time is so “out of joint,” he is unable to seamlessly and speedily avenge his father’s murder. Leon’s version shapes a familial revenge tragedy. Once set on its course, dire events cannot be averted, for at the core is the initial corruption, “the primal eldest curse, a brother’s murder” that “smells to heaven.” From that there is no turning, until justice is served, the sooner the better.

In this 61st offering of Free Shakespeare in the Park, we immediately note the conceit of corruption and its ill effects to skew the right order of things, making them “out of joint,” off-kilter. This is an important theme of the play (expressed by Hamlet) and represented by Beowulf Boritt’s set, some of which is a wrecked-out remnant of his design from Leon’s pre-Covid production of Shakespeare’s comedy, Much Ado About Nothing.

That 2019 design sported a resplendent, brick, Georgian mansion that stylistically conveyed the wealth and rectitude of its Black, lordly owners rising up in a progressive South. Hope was represented by a “Stacy Abrams for President” campaign sign proudly displayed on the side of the building. A towering flagpole and American flag patriotically stood like a sentinel at the ready. Peace and order reigned.

It is not necessary to have seen Much Ado About Nothing to understand the ruination and disorder foreshadowed by Boritt’s Hamlet set which coherently synthesizes Leon’s themes for his modernized version. In one section a tilted smaller version of the former Georgian house appears to be sinking off its foundation. On stage left, an SUV is tilted off center, undrivable, in a ditch. The Stacy Abrams’ sign is torn and displaced on the ground like discarded trash. And the American flag with its long flagpole angled toward the ground signals distress and a “cry for help.”

The only ordered structure is the cutaway of a building center stage (used for projections), whose door the characters enter and exit from.

Boritt’s set design suggests “something is rotten” unstable and “out of joint” in this kingdom. Themes of devolution are foreshadowed. From unrectified corruption comes disorder which breeds chaos and dark energy, out of which destruction and death follow. And all of this springs from the unjust murder of the deceased in the coffin that is draped in an American flag and placed center stage. It is his life which is celebrated by the beautiful singing of praise hymns at his well-attended funeral in the prologue of Leon’s Hamlet. It is his life that is memorialized by the huge portrait of the kingly father in military dress which hangs watchful, presiding over events from its position on the back wall of the only part of the set that is not wrecked and disarrayed.

Cutting Act I scene i (soldiers stand on guard watchful of an attack from Norway), Leon opens with the elder Hamlet’s funeral. A Praise Team joined by a Wedding Singer, who we later recognize to be Ophelia (the golden-voiced Solea Pfeiffer), sing with beautiful harmony. Jason Michael Webb created the music and additional lyrics which set out the Godly tenets that all are importuned to follow or live by. To their downfall they don’t and this is manifested in tragedy.

Importantly, the first three songs are taken from the Bible. The first is from Ecclesiastes (“To everything there is a season). Then follow Matthew 5 (“To show the world your love, I’m goona let it shine”) and I John 5 (“When you go on that journey you go alone”). The last song that Ophelia sings is composed of lines from a love poem that Hamlet wrote for her.

The songs intimate the former moral rectitude and divine unctions found in the former Hamlet’s kingdom. Ironically, the memorial service represents the last peace that this kingdom will appreciate. As the set indicates, wrack and ruin have already begun. The scenes after the funeral represent declension and growing darkness. And after old Hamlet is buried, nothing good follows.

Numerous cuts (scenes, lines, characters) abound in Leon’s version. His iteration presents questions about the disastrous consequences of familial revenge which is different from Godly justice suggested by the songs. Importantly, Leon’s update (sans scene i) gets to the crux of the conflict with scene ii, the marriage celebration of Claudius (the terrific John Douglas Thompson and Gertrude (Lorraine Toussaint is every inch Thompson’s equal). We note their public affection for one another, which Hamlet later intimates is a lust-filled marriage in an “unseemly bed.” The partying has followed fast upon the old Hamlet’s burial, to the dismay and depression of his loyal son.

It is during the festivities when the sinister intent of the new king and duped mother Gertrude chide Hamlet (the fabulous Ato Blankson-Wood). They suggest he put off his mourning clothes, “unmanly grief” and depression for it is “unnatural.” Already, the cover-up has begun and Hamlet is the one individual Claudius must be circumspect about as the rightful heir to a throne which he usurped.

Gertrude importunes Hamlet to remain in the kingdom instead of returning to his studies in Wittenberg, and dutifully, he obeys, stuck with the daily reminder of his father’s death and mother’s “o’er hasty marriage.” This version emphasizes Claudius’ sincerity covering over his suspicion and fear of Hamlet. He is happy to keep him under his watchful eye. Throughout his magnificent portrayal, Thompson’s Claudius gradually reveals his underlying guilt and fear for his crimes of regicide and fratricide. We see his behavior grow more and more paranoid about Hamlet as the conflict between them grows and Hamlet unloads snide remarks on Claudius, Polonius and all those who are obedient to the usurper king as a provocation.

Leon’s version is a familial revenge tragedy which eliminates any reference to Norway or Prince Fortinbras seeking justice for his father’s death in battle with Denmark. Leon is unconcerned with Norway and Fortinbras. The conflict in his Hamlet is internal to Denmark, a divided kingdom like “an unweeded garden, rank and gross in nature.” Divided against itself, with brother vs. brother and son vs. uncle, and Gertrude the exploited, seduced pawn, Claudius’ guilt is a canker worm which gnaws at him. Likewise, gnawing at Hamlet after his father’s ghost’s visit, is the knowledge of what has to be done. But he maintains, “cursed spite, that ever I was born to set it right.”

All is covert and the truth is covered up. Polonius and Claudius spy on Hamlet to divine why he is “mad,” and Hamlet acts mad and rejects Ophelia’s love during the process of divining whether the ghost is telling the truth. Intrigue, chaos and darkness augment and have their way with the innocent and guilty. For Hamlet, the “time is out of joint.” An intellect, he is “blunted” (the ghost later says) from making the correct decisions or acting upon them in a timely fashion. The darkness that Claudius has set loose taints Hamlet and every principal character that must show obeisance to King Claudius’ illegal reign.

Key to the argument of choosing vengeance vs. justice is the enthralling scene when Hamlet meets his father’s ghost. Initially, the creative team (Jeff Sugg’s projections, Allen Lee Hughes’ lighting design, Justin Ellington’s sound design) present the father’s ghost on the back wall with projections on the portrait and the wall, accompanied by the ghost’s booming, shattering voice, which commands Hamlet’s obedience.

But at the description of the murder, the ghost possesses Hamlet. Blankson-Wood’s performance of the ghost consuming his soul is phenomenal and physical. He arches his back with the jolt of spirit possession and then rights his gyrating body as his father’s voice spews wildly from him, eyes rolled back, arms waving, the very picture of the demonic that Horatio (the fine Warner Miller) warned Hamlet might “tempt him to the flood.” At once frightening and mesmerizing, the possession enthralls us and changes Hamlet. It is a dynamic, successful scene showing the decline in the goodness from the initial praise songs to the devolution of the spirit’s will demanding vengeance. We are thunderstruck. Blankson-Wood’s authenticity frightfully convinces us of the spirit’s potential for evil misdirection into a vengeance which is not just and will bring devastation.

After the ghost leaves the vessel it inhabited and Hamlet swears Horatio and Marcellus (Lance Alexander Smith) to secrecy, Hamlet’s fate is sealed. He moves toward faith in the ghost, farther away from the light-filled unctions in the songs at his father’s funeral. Now, there is no “showing love” and “shining one’s light.” Intrigue and acting “mad” and conspiracy and cover-up overtake the mission of the kingdom. Hamlet toys with and ridicules Polonius (Daniel Pearce gives a humorous, organically funny portrayal) and does the same with Ophelia in a powerful scene, eschewing his love for her. Pfeiffer’s Ophelia shows her devastation and shock. His behavior is a complicating truth for everyone and it intensifies Hamlet’s conflict with Claudius.

Knowing Hamlet’s madness is not for Ophelia’s love, Claudius grows more paranoid and guilt laden. Clearly, when the actors make their presentation of the dumb show (Jason Michael Webb’s song “Cold World” is superb), and Hamlet presents ‘The Murder of Gonzago,’ he and Horatio see that Claudius’ guilty conscience is made manifest in ire and defensiveness. Though this scene is truncated, as is Hamlet’s description of how the actors should proclaim their speeches, no coherence is lost. Claudius runs away, his soul uncovered. Hamlet is convinced vengeance is the right course of action. But he has allowed himself to be misguided. Nothing good will come of following the ghost’s lead.

Leon truncates the minor speeches, retaining those that convey Hamlet’s angst at being stuck in the kingdom which is a prison. He can’t commit suicide (“To Be or Not to Be”) because his morality and fear of death forbids it. Stuck in Denmark, everyone is a potential enemy except Horatio. He uses coded speech with everyone especially Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, who Claudius/Gertrude have engaged to spy on him. Ato Blankson-Wood delivers the key soliloquies powerfully with insight as he makes the audience his empathetic confidante who understands his intellect has chained him to inaction. We are drawn into his plight, but become frustrated when his determination falters.

The paramount event where his intellect intrudes happens when Claudius is praying in the church (fine stylized staging). Coming upon Claudius, Hamlet rejects the opportunity to kill him because he thinks Claudius is confessing his sins and getting right with God. However, it is a missed opportunity which Hamlet squanders because Claudius’ prayers fail (“my words fly up, my thoughts remain below; words without thoughts never to heaven go.”). Claudius realizes to receive forgiveness he would have to give up the throne, Queen and his cover-up which he will never do.

Hamlet lacks proper discernment and moves from his bad decision to impulse. Not killing Claudius in the church, he rashly and mistakenly kills Polonius, assuming incorrectly that Claudius quickly ran up to Gertrude’s room. The stakes are raised for Claudius and Hamlet. Polonius’s death missing body incense Claudius who is overwrought with fear knowing his enemy Hamlet has put a target on his back.

Once more, the “time is out of joint,” and Hamlet defers vengeance and subjects himself to Claudius, finally revealing where Polonius’ body is. For Gertrude’s sake, Claudius sends Hamlet away with the orders for others to kill him in a plan that fatefully backfires.

Leon’s version has clarified the stakes for Claudius to escape accountability, manipulating Laertes (Nick Rehberger) from killing him by blaming Hamlet. Thompson conveys each of these cover-ups with precision. Also, clarified is Blankson-Wood’s angst and struggle confronting his father’s murderer. His use of irony as a weapon to prick Claudius’ conscience is superbly rendered as are his soliloquies whose philosophical constructs tie him in emotional knots. Hamlet, knowing that he is stuck in a morass with no way out, recognizes that like the other characters, he is on a collision course with destiny and ruination which is foreshadowed at the beginning with Boritt’s set.

Also, clarified in this version is Toussaint’s Gertrude who is in a state of ambivalence and guilt stirred by Hamlet’s antic behavior, which she suspects is his response to her marrying Claudius. When their confrontation occurs after Hamlet kills Polonius, she knows her relationship with Claudius must be thrown over, yet she hesitates and discusses Hamlet with Claudius ignoring Hamlet’s wise counsel. The doom she recognizes in Ophelia’s madness will only bring more sorrows, a trend which both Claudius and Gertrude comment upon. Toussaint’s description of Ophelia’s drowning is heartfelt and mournful.

The flow of events coheres because the through-line of Claudius and Gertrude in conflict with Hamlet is maintained with intensity. Stripping Norway from the action and leaving Fortinbras out of the conclusion is to the purpose of Leon’s emphasis of the familial tragedy. The contrast of the good son and man of action who achieves justice (Fortinbras) with Hamlet’s flawed son of inaction who is Fortune’s fool, exacerbating destruction via revenge gone wrong would have pleased Queen Elizabeth I. Contrasting the two Prince’s and showing the heroic one in Fortinbras is an encouragement of how royalty should rule. However, it doesn’t fit with the themes that Leon emphasizes, especially that a “house divided against itself cannot stand.”

Hamlet concludes with the slaughter of two families tainted by their association with a corrupted king, out from which there is no release except death. A final theme current for our time suggests that unless individuals stand against usurpers of power, the usurper and all who are his accomplices by not bringing him to justice will pay the forfeit of their lives and fortunes.

However, only Miller’s Horatio understands the full story of Hamlet and the striving between vengeance and justice. That vengeance brings disaster is why the ensemble finishes with the actors’ song that they sang when Hamlet first meets them. It is poignant and true and heartfelt when the spirit of Ophelia joins them and together they sing, “I could tell you a tale, God’s cry. It could make the God’s cry.”

Kudos to the ensemble and the creative team who carry Leon’s vision of Hamlet into triumph. These include those not already mentioned: Jessica Jahn’s colorful costume design, Earon Chew Nealey’s hair, wig and makeup design, Camille A. Brown’s choreography and Gabriel Bennett for Charcoalblue and Arielle Edwards for Delacorte’s sound system design.

For tickets to this unique Hamlet which has one intermission, go to their website https://publictheater.org/productions/season/2223/fsitp/hamlet/

‘Days of Wine and Roses,’ Truthful, Poignant, a Stunning Triumph

Alcohol is different from other addictive drugs. It’s a part of our culture and integral to events around professional and social situations. It’s legal and easy to purchase. But for those who can’t “live” without it, alcohol is both a blessing and a curse. Days of Wine and Roses currently at Atlantic Theater Company until July 16th encapsulates the joy and emotional horror of the drinking disease. The production is a complicated, profound, assailable to the senses, cathartic must-see.

Adam Guettel’s music and lyrics spin out the anatomy of alcoholism in the dynamic of a couple’s relationship. The couple, portrayed by the exceptional Kelli O’Hara and Brian d’Arcy James, are forced to confront their psychological weaknesses manifested by their alcoholism. Guided by Craig Lucas’ book, Guettel relays the extremes of euphoric addiction and its impact on the emotions of the characters with his expressionistic score and lyrics that appear to be lighthearted and lyrical but mirror undercurrents of desperation and loneliness.

Lucas nails down Joe and Kirsten’s alcohol dependent relationship dynamic with precision and poignancy. He carries it through to the point when d’Arcy James’ Joe Clay comes to the end of himself. Out of love he waits and hopes for O’Hara’s Kirsten to want to recover from alcoholism. This uncertain state promises to usher in a long, hard wait for Kirsten to admit she is ill and needs help.

Directed by Michael Greif, Days of Wine and Roses is a journey of devolution and evolution that displays the characters’ emotions of exuberance, sorrow, unforgiveness, self-discovery, redemption, self-annihilation, humiliation and love. Above all, it reflects the tragedy and joy of human experience, either confronting one’s individual consciousness or running from it, until one finally acknowledges that they must change or kill themselves.

Based on the titular 1958 teleplay by JP Miller and the 1962 Warner Bros. film, the musical is produced by special arrangement with Warner Bros. Theatre Ventures. Importantly, once again it brings together the successful Lucas and Guettel team who created The Light in the Piazza. Kelli O’Hara, who sang the lead in that Broadway production, encouraged this project.

Key to understanding this musical that is set in 1950 and lightly references the cultural mores of the time (sexism and paternalism) is that Alcoholics Anonymous’ 12 step program (never named) identifies alcoholism as a disease and not just a “drinking problem.”

The production frames how Joe and Kristen’s love blossoms with their drinking. It acutely underscores that the disease elevates their mood and pleasure centers (“There I Go,” “Evanesce” “As the Water Loves the Stone”) with pernicious allurement. Indeed, it is the linchpin to how they initially become involved with each other and why Kristen refuses to stay with Joe and her daughter after he combats his illness by meeting with other alcoholics to stop his self-destructive patterns.

The characters’ dynamic is emphasized when they meet at a business party on a yacht in the East River. A nondrinker, Kristen eschews alcohol. On the other hand Joe persists in getting her to be his drinking buddy. She resists him and his advances because she doesn’t like the taste of alcohol nor his smarmy, belittling, fake PR patter and persona.

It is only when she upbraids him and he apologizes for “starting off on the wrong foot” that she relents and suggests they leave. Her honesty and authenticity charm Joe and allow his better self to emerge. Together at a quiet restaurant, they discover qualities in each other that they can appreciate and adore.

As they establish a friendship, Joe introduces her to a Brandy Alexander (she loves chocolate) and she discovers her subsequent enjoyment of the buzz it gives her. This drink and others draw her to Joe as they gradually become boozy partners, who “in their continual high,” eventually marry and have a daughter, despite her father’s (the excellent Byron Jennings) disapproval and distrust of Joe. She and Joe have made a commitment to each other. Determined, O’Hara’s Kirsten will not allow her father Arensen to sway her from establishing a family with her lover and partner in drinking.

As Kirsten, Kelli O’Hara creates a complex portrayal of a woman whose drinking subterfuge eventually splits open her soul weakness after seven years of marriage and taking care of their daughter Lila (Ella Dane Morgan). Covertly, she sneaks drinks as she completes household chores and plays with Lila. O’Hara’s “Are You Blue,” “Underdeath and “First Breath” (the latter sung with Morgan’s Lila) reveal the roiling undercurrents of unhappiness and her attempts to deal with depression as the absent Joe, who works in Houston, barely keeps himself functioning at a job that requires he drink to entertain clients.

Brian d’Arcy James’ vibrant, alcohol-alluring, loving Joe allows her to take the lead, while he cleverly introduces her to a new world of drinking, fun and happiness. He draws her to him and maintains their closeness and joy, but such adventures are always fueled by alcohol. Initially, like any disease that manifests slowly, they convince themselves they are in control and live together as a successful family.

However, all is upended the seventh year of their marriage. A spectacularly destructive circumstance set off by Kirsten’s alcohol blackout destroys what they have built together (conveyed fearfully thanks to Lizzie Clachan’s sets, Ben Stanton’s lighting and Kai Harada’s sound). As their family spirals downward, their only hope of rehabilitation lies under her father’s condemning watchfulness, when they plead for his help and he gives them food, shelter and work in his greenhouse business.

The arc of their destruction is born out of their compulsions, one of which is their susceptibility to the pleasure of alcohol, the other, the belief they can ignore their desire to harm themselves and each other as addicts.

After months of sobriety, Joe breaks down, buys alcohol and offers it to Kirsten (“Evanesce” reprise), then goes completely “off the rails” (“435”) looking for a bottle he has hidden in the greenhouse. In anger at himself for his weakness and fury in not finding the bottle, he becomes rebellious. Turning against his judgmental father-in-law who has given them a chance, Joe destroys the greenhouse that Arnesen has made into a profitable business. When he finds the bottle, he drinks himself unconscious and lands on his back in the hospital on the brink of death.

Kirsten and Arnesen refuse to believe this is a disease that has no cure except through a way provided by a volunteer who is also an alcoholic, Jim Hungerford (David Jennings). Jim belongs to an association of alcoholics who understand that the only path away from the disease is through meetings, readings and the community of others who need each other’s help and camaraderie. Arensen dismisses Joe’s attempt at reconciliation and recovery. He bans Joe from his presence as an evil influence. The family are on their own in a dingy apartment as Joe allows himself to be helped by Jim while Kirsten refuses to admit she needs help and rejects Jim’s offers.

The apex of their relationship involved the ecstasy of alcohol. Kirsten appeals to Joe’s love and the remembrance of the fun they had (“Morton’s Salt Girl”) with a soft shoe in salt poured on the floor, created by Sergio Trujillo and Karla Puno Garcia. The song attempts to rekindle the magic when they enjoyed being drunk together. However, Joe’s eyes have been opened and Jim’s voice resides in his heart with the growing strength that he can conquer his illness. Sadly, Kirsten interprets this as rejection and a killing off of their love. She criticizes Joe for making her feel ashamed of herself and victimizing her with guilt and pain.

As Joe affirms his confidence that he can change to Jim in the powerful “Forgiveness” Joe and Lila cling to each other and KIrsten eventually stays with her father whose judgment, though problematic, is better than the humiliation and weakness she feels around Joe, who is passionate about healing and recovering. Now Joe’s love in sanctimony drives her away.

Days of Wine and Roses is poignant and current for our time, taking us beyond the beautiful period costumes by Dede Ayite and hair design by David Brian Brown. Kelli O’Hara is affecting and brilliant. Her operatic, rich and plaintiff voice in the concluding songs elicits our empathy. Her aloneness and sorrow at losing her partner to sobriety is intensely human and real. Her rejection of Joe’s help and love beyond the haze of alcohol is frightening.

Brian d’Arcy James is superb in reveling the nuances of determining his own confidence to overcome his addiction. Yet, he mines Joe’s attempt to balance the authenticity of being happy with his sober self with his love for Kirsten without their alcohol infusions. Together these amazing actors bring home the production leaving the audience with a confluence of feelings that will not be easily forgotten.

Kudos to the ensemble and the technical creatives and Greif’s direction and vision. With additional kudos to music director Kimberly Grigsby, Adam Guettel’s orchestrations and Jamie Lawrence’s additional orchestrations.

Days of Wine and Roses runs one hour and forty-five minutes with no intermission. For tickets and times go to the Atlantic Theater Company website https://atlantictheater.org/production/days-of-wine-and-roses/

‘The Comeuppance,’ a Pre-Reunion Reunion of Five Friends and Death, Theater Review

In The Comeuppance by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, directed by Eric Ting, old friends meet for a pre-reunion reunion at the home of Ursula (the superb Britney Bradford), who has organized a party to celebrate before she sends off friends to their twentieth reunion. In an extension of its World Premiere at the Signature Theatre, the comedy with somber, stark elements was extended until July 9th by popular demand.

Jacobs-Jenkins’ (Appropriate, An Octoroon) themes are timely. The ensemble was spot-on authentic and natural. In his two hour play with no intermission millennials admit the consequences of living with unsound decisions made in the less scrupulous years of their youth. Sooner or later, there is a “comeuppance.” One cannot escape the inevitability of oneself and one’s mortality, as Death, who like a sylph inhabits each of the characters, periodically reminds us.

To effect this principle theme of death in life and the transience of all things, Jacobs-Jenkins places thirty-somethings in a backyard with drinks, weed and a loaded, shared past. They once were part of a high school friend group called M.E.R.G.E.: Multi Ethnic Reject Group. Jacobs-Jenkins allows them to go at each other (Emilio’s bitterness is apparent), as they bond over a perceived closeness, which may not have existed after all.

But first, Death introduces himself after slipping into the soul of the protagonist Emilio (Caleb Eberhardt), who has the most difficult time struggling to let the past remain in the past so he can create a better life for himself. As he does with all the characters, Death speaks through Emilio. He warns the audience he is always lurking in omnipotence, with a complete understanding of who human beings are, including the audience members, which he crudely, fearfully reminds us of, once more at the conclusion.

Since last they met, Emilio, Caitlin (Susannah Flood), Paco (Bobby Moreno) and Kristina (Shannon Tyo) have established careers, been to war, gotten married and had kids. Each in their own way has confronted loss, confusion, cultural chaos and most recently COVID-19. We learn that all have been under an emotional siege. Some are sustaining the sociopolitical chaos that Emilio points out better than others, as they either ignore it, reflect upon it, or allow their own lives and difficulties to blot it out of their consideration.

Interestingly, the generous Ursula, whose home, inherited after her grandmother’s death, has been offered up for the celebration, becomes the first to manifest the ravages of millennial time and aging. She has lost her sight in one eye, having contracted diabetes. She tells the others that she is not up to going to the reunion and they may stay as long as they like at her party.

As Emilio, Caitlin and Ursula wait for the others, Emilio’s irritability spills out in humor against Caitlin, whom he once dated in high school. She has married an older man who is a Trumper, which upsets Emilio. Their two children her husband has from a first marriage appear to be doing well: one is finishing college, the other is beginning a career. Thanks to the actors who present their characters with moment, as the characters cath up their lives, the segment never completely falls into tedium. The characters reacquaint as they step into familiarity with Ursula reminding them of M.E.R.G.E codes they used in high school.

During this segment Death manifests a presence in the monologues from Ursula and Caitlin. They heighten their soul revelations and reflect another aspect of their ethos that is not apparent on the surface.

When Kristina, a doctor with “so many kids” arrives bringing her cousin Paco, who once dated Caitlin and treated her badly, the hilarity increases. It is driven to its peak with the characters’ fronting as a means of getting their “land legs” with each other. By this point the drinks and weed have kicked in and Emilio confronts Paco. whom he clearly distrusts and despises. More revelations erupt and we note Paco’s and Kristina’s individual unhappiness. Once again, Death inhabits Kristina and Paco and expresses their soul’s interior.

Throughout the play Jacob-Jenkins contrasts the material realm and the illusory fitted by human delusion that these individuals have “all the time in creation” to live their lives against the immutable truth of life’s impermanence. Speaking with quietude and without passion, Death assures us he “has their number.” He matter-of-factly reminds us that entropy is king. Things fall apart; human bodies, human relationships, all we hold dear is smothered in half-truths and lies, for we die.

Then the limo arrives and with it well-worked confusion. Ursula goes off to the reunion that Emilio never attends. With the door locked against him and all his buddies gone, he sleeps on the porch, a hapless, solitary and alone soul who needs to “get himself together” emotionally, expiate the past and forgive himself for his failings.

When Ursula returns, we learn the extent of the lies of omission as Eberhardt’s Emilio allows the truth to flow and Ursula shares with him what she couldn’t reveal before. Then Death through Emilio takes his final “comeuppance.” While she “sleeps in her mind” he expresses that his target is Ursula in the immediate future. He discusses that how she will end up is exactly as her friend Caitlin fears. Despite Emilio’s offering to marry and take care of her, Ursula puts him off because she has someone. It turns out, it’s another poor decision for both of them.

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins has woven an interesting conceptual piece that is uneven especially in segments where there is too much ancillary discussion by characters. There is an overabundance of unnecessary detail that impede the forward momentum of the dynamic that occurs on the porch of their lives. In these sections, I dropped out. Perhaps wise editing would make the segments more vital and immediate.

Nevertheless, the actors are terrific. They make the most of the unevenness that drives the play toward the characters’ acknowledgement of duality: of experiencing life and watching and reflecting oneself living it in the knowledge that they are mortal.

The difficulty of this duality is dealing with the reality of Death. In the play it is animated through the characters for our benefit. However, in their lives, it is ever-present in the form of gun massacres, the war in Iraq and Afghanistan, political subterfuge and sabotage in January 6th which attempted to signal in the “death” of our democracy. All of these, Death’s cultural possessions, have brought the characters’ millennial generation to the brink, Emilio acknowledges. That and their body’s frailty is their comeuppance, Ursula suggests.

Though each generation has had its cataclysms, it is the millennials “no way out” that Emilio especially confronts while the others seem to ignore it, save Ursula. Unfortunately, our culture doesn’t do death well and entertainment capitalizes on its particularly gruesome features in the proliferation of horror stories and films. Jacobs-Jenkins counters this aspect, making it a homely creation of back porches. And as he reminds us no one “gets out alive,” at least there is humor. We can laugh on our way out of life’s conundrums, miseries toward Death’s grasp.

Look for this play to be produced elsewhere. And check out their website for more information at https://signaturetheatre.org/

‘Primary Trust,’ the Hope of Friendship Through The Trauma of Being Alone

Small town life can be incredibly boring and static. However, for those who experienced unaccountable pain and trauma, the peace and quiet may be precisely what is needed to achieve a balanced state. In Eboni Booth’s sensitive, profound drama Primary Trust, currently at Roundabout Theatre Company until July 2nd, the playwright investigates humans in their ability to heal from trauma.

For some, getting beyond the pain of emotional loss requires a particular kind of remedy. Kenneth (William Jackson Harper), a resident of Rochester suburb, Cranberry, New York, has found the ability to withstand loss through his mind and will’s resilience to nurture itself with hope and friendship.

Kenneth addresses the audience directly relating a sweetness and shy vulnerability that is immensely likable. He introduces the town and his friend Bert to the audience with ease and authenticity. When there is a segue in thought and feeling, a bell rings as an accompaniment by musician Luke Wygodny who also plays the cello and other instruments before the play begins and during salient turning points.

Harper’s Kenneth takes his time to gather his thoughts as he confesses to us. His need to share his story resonates. Clearly, his story is momentous and universal. Praise goes to William Jackson Harper who engages us with his humanity. Additionally, Eboni Booth’s simple word craft in structuring likable, recognizable, human characters in this small town is amazing. With fine direction by Knud Adams, who shepherds Harper’s Kenneth and the supporting actors, we become captivated and empathize with Kenneth though we may have little in common with him.

Kenneth shares his experiences about “what happened” to him at a turning point in his life when he is thirty-eight years old. He gives us background and reviews his daily routine in Cranberry, New York focusing on the high point of his day after work, when he spends the evening at Wally’s, a typical tiki bar/restaurant. There, he joins his BFF Bert (Eric Berryman) and they drink Mai Tais and share jokes and stories. Their affection and warmth is genuine as they reminisce about past experiences in the joyful atmosphere of booze and camaraderie.

However, apart from their bonding daily at Wally’s and their race, the men are very different. Kenneth works at a bookstore and has been invaluable to his boss, Sam (the on-point Jay O. Sanders) doing bookkeeping, clerking and various chores. Bert on the other hand has an office job, a wife and children, whom he leaves to be with Kenneth in the evenings. It is around about this time that reality fuses with the ethereal, and logic is throw out the window. How the playwright, director and Harper’s portrayal of Kenneth massage us to accept this maverick dramatic element is a testament to their talent and genius.

Kenneth explains that his friend Bert is invisible, imaginary. In other words his BFF can only be seen by him (and of course us). Thus, we become intimates. In confiding to us, Kenneth trusts us to share his secret, in the hope we will not judge him and “turn off” because he’s “wacky.”

Sam is aware that Bert is Kenneth’s imaginary friend. When he tells Kenneth he is selling the store and relocating for health reasons, he makes it a point to reference Bert. He suggests when Kenneth looks for another job, he shouldn’t allow Bert to intrude on the interview. Nor should he share with prospective employers that Bert is his imaginary friend. The implication is that they will think Kenneth is deranged. That we accept Bert as imaginary and go along for the ride is creditable to the playwright, director and actors.

Sam’s news about closing his store is an earthquake. Kenneth discusses the impact on his life with Bert and a new Wally’s waitress Corrina (April Matthis). Though Sam’s move shakes Kenneth, it is an opportunity. He is forced to end the nullifying status quo must. Change occurs in Kenneth’s discussions with Bert and Corrina, who suggests the bank Primary Trust is looking to hire tellers. When Kenneth applies for a job and speaks with Clay who is the branch manager (Jay O. Sanders), all goes well. Humorously, Bert accompanies him to the interview and prompts Kenneth’s winning responses which seal the deal. Clay hires him and he becomes one of the best employees of the bank.

However, Kenneth must confront a transition moving in his soul. The stirrings begin when he and Corrina as friends move beyond Wally’s to a lovely French restaurant. In a humorous turn Jay O. Sanders is the French waiter who serves them. It is in this new expansive world with Corrina that possibilities open up for Kenneth. For the first time, Kenneth doesn’t meet Bert at Wally’s It is another earthquake that rocks him off the status quo of his insular life. There is no spoiler alert. You’ll just have to see this heartfelt production to discover what happens next.

William Jackson Harper is absolutely terrific in a role which is elegantly written for the quiet corners of our minds. The supporting cast are authentic and vital in filling out the life that Kenneth has made for himself to help him emerge out of his cocoon and begin to fly. The playwright’s courage to present an extraordinary friendship which serves Kenneth to bring him to a point of sustenance until he launches into success is beautifully, subtly conveyed. Thanks to the ensemble, who make the unbelievable real, Kenneth’s “small life” in its human drama is important to us.

Thus, when Kenneth explains his upbringing to Corrina toward the end of the play, his revelation stuns. The clues coalesce and we “get” who he is, understanding his brilliance, his tenacity and perseverance. It brings to mind the character of Jane Eyre (in the titular novel), whose dying friend tells her, “You are never alone. You have yourself. ” The playwright takes this notion further to suggest, when you feel you can’t trust yourself, primarily, you can always elicit an imaginary friend who is closer than a brother or sister, until it is time for them to leave. It is through this “primary trust” one survives through heartbreak, trauma, isolation and death.

Primary Trust‘s fantastic qualities enliven the themes and remind us of the importance of doing no harm as we negotiate aloneness in our own soul consciousness. Kenneth chose his friend wisely. He relates how this occurs to Corrina who listens, the active ingredient of his budding friendship with her.

Kudos to the set designer Marsha Ginsberg,Isabella Byrd’s lighting design, Mikaal Sulaiman’s sound design, Qween Jean’s costume design, Niklya Mathis’ hair & wig design and Like Wygodny’s original music which to tonally balance the production. The mock up of the town square offered a metaphoric quaint suburb at a time before the technological explosion and cell phones when people listened to each other live and as Kenneth does created conversations with ethereal friends. The set design and music created the atmosphere so that we readily accept Kenneth’s and Bert’s friendship and its significance with wonder and surprise.

For tickets and times to see Primary Trust, go to their website https://www.roundabouttheatre.org/get-tickets/2022-2023-season/primary-trust/performances

‘The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window,’ Lorraine Hansberry’s Mastery of Ideas in a Superb Production

Oscar Isaac’s Sidney Brustein in Lorraine Hansberry’s most ambitious play, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window (directed by Anne Kauffman) never catches a break. Hansberry’s everyman layman’s intellectual is in pursuit of expressing his creative genius and achieving exploits he can be proud of. When we meet him at the top of Hansberry’s masterpiece, which is full of sardonic wisdom, sage philosophy and political realism, Sidney is a flop looking for a reprieve. This revival, first produced on Broadway in 1964, was tightened for this Broadway revival (one noticeable end sequence with Gloria was shaved, not to the play’s betterment). Currently running at the James Earl Jones Theatre with one intermission, the production boasts the same stellar cast in its transfer from its sold out run at BAM’s Harvey Theatre in Brooklyn. The production is in a limited run, ending in July.

It is to the producers’ credit that they risked bringing the play to a Broadway audience, who may not be used to the complications, the numerous thematic threads, the actualized brilliance of unique characterizations and their interrelationships, and Hansberry’s overall indictment of the culture and society. Sign is a companion piece to her award-winning Raisin in the Sun. It explores the root causes why the Younger family is where it is socially and economically. Vitally, it examines the political underpinnings of institutional oppression and discrimination via reform movements, symbolized by the efforts of Brustein and friends who promote the reform candidacy of Wally O’Hara.

To focus her indictment of the perniciousness of political and social oppression, Hansberry examines the vanguard of reformists, Greenwich Village artists, activists and journalists who are emotionally/philosophically ready to make social/economic change of the type that the Younger family in Raisin in the Sun yearns for. However, these Greenwich Village mavericks are the least equipped tactically to sidestep co-optation and the political cynicism of the power-brokers. They realize too late that the money men will fight them to the death to maintain a status quo which inevitably destroys the vulnerable and keeps families like the Youngers and drug addict Willie Johnson struggling to survive.

The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window is timeless in its themes and its characterizations. When we measure it in light of current social trends, it is fitting that the play transcends the history of the 1960s in its prescience and reveals political tropes we experience today. Additionally, it suggests how far society has declined to the point where cultural and political co-optation (a principal theme) have been institutionalized via media that skews the truth unwittingly. The result is that large swaths of our nation remain oblivious to their exploitation and dehumanization, ignorant that they are the pawns of political parties, who promise reform then deliver regression. In short they, like Sidney Brustein and his friends, are seduced to hope in a better world that reform politicians say they will deliver. But when they win, through a plurality of votes from a diverse population, they renege on their promises and continue to do what their “owners” want, which is to “screw” the little people and deprive them of power and a “place at the table.”

Hansberry’s setting of Greenwich Village is specifically selected as one of the hottest, most forward-thinking, “happening” areas in the nation. Brustein’s apartment is the focal point where we meet representative types of those found in sociopolitical/cultural reform movements. His community of friends are activists who believe their friend and candidate Wally O’Hara (Andy Grotelueschen), is positioned to overturn the Village’s entrenched “political machine.” Sidney, reeling from his bankrupted club, which characterized his cultural/intellectual ethos (idealistically named Walden Pond after Henry David Thoreau’s book), purchases a flagging newspaper (The Village Crier) to once again indulge his passion for creative expression. He does this unbeknownst to his wife Iris (Rachel Brosnahan), a budding second-wave feminist who waitresses to support them financially. She chafes at her five-year marriage to Sidney, shaking off his definitions and the identities he places on her, one of which is his “Mountain Girl.”

Activist and theoretical Communist (separated from the genocidal Stalinist despotism) Alton (Julian De Niro), drops in with O’Hara to encourage Sidney to join the crusade to elect O’Hara with the Crier’s endorsement. Sidney declaims their persuasive rhetoric and assures them that he will never get involved in political activism again. However, as events progress, his attitude changes. We note his friends, including artist illustrator Max (Raphael Nash Thompson), stir him to support O’Hara with his excellent articles. Sidney, mocked by Iris about his failures, is swept up in the campaign. When he hangs a large sign in his window that endorses O’Hara, his adherence to push a win for the “champion of the people” increases in fervency.

The sign symbolizes his hope and his seduction into the world of misguided activism, but its meaning changes over the course of the play. Hansberry doesn’t reveal the exact moment that Sidney decides to take up the “losing cause” after he disavowed it. However, his fickle nature and passion to be enmeshed in something “significant” with his friends helps to sway him.

In the first acts of the play, Hansberry introduces us to the players and reveals the depth of her characterizations as each of the characters widens their arc of development by the conclusion. We note the development of Mavis (Miriam Silverman), Iris’ uptown, bourgeois, housewife sister, who is married to a prosperous husband and is raising two sons. We also meet David Ragin (Glenn Fitzgerald), the Brustein’s gay, nihilistic, absurdist playwright friend, who lives in the apartment above theirs and is on the verge of success. Both Mavis and David, like Sidney’s other friends, twit him about Walden Pond’s failure. Mavis and Iris are antithetical in values and Mavis views her sister and brother-in-law as Bohemian specimens to be observed and secretly derided as entertainment. We discover Mavis’ bigotry when she opposes the union of their sister Gloria (Gus Birney), a high class call girl, to Alton, the young light-skinned Black friend.

The genius of this work is in Hansberry’s dialogue and the intricacies of the characterizations. It is as if Hansberry spins them like tops and enjoys the trajectory she creates for them, which ultimately is surprising and sensitively drawn. Organically driven by their own desires, we follow Sidney and Iris’ family machinations, pegged against the backdrop of a political campaign that could redefine each of their lives so that they could better fulfill their dreams and purpose. However, the campaign never rises to the sanctity of what a true democratic, civic, body politic should be. Indeed, the political system has been usurped in a surreptitious coup that the canny voter “pawns” are clueless about.

Tragically, instead of political power being used to combat the destructive forces Hansberry outlines, some of which are discrimination, drugs, law-enforcement corruption, economic inequity and other issues that impact the Brustein’s and their friends’ lives, O’Hara and his handlers have other plans. But first, they cleverly convince the voters a win is unlikely and they pump them up to believe in the possibility of an O’Hara success that would be earth-shattering and revolutionary. This, we discover later, is a canard. The “revolutionary coup” can never occur because the political hacks control everything, including Sidney’s paper which they exploit to foment support for O’Hara. How Hansberry gradually reveals this process and ties it in with the relationships-between Iris and Sidney, Alton and Gloria, Iris and Mavis and the other friends-is a fabric woven moment by moment through incredible dialogue that pops with quips, peasant philosophy, seasoned wisdom, and brilliant moments that evanesce all too quickly.

By the conclusion, the solidity of the characters’ hopes we’ve seen in the beginning have been dashed to fold in on themselves. Both Iris and Sidney learn to reevaluate their relationship with each other and their misapplication of self-actualization, which allowed a tragedy to happen. Likewise, Alton’s inflexibility about his own approach to his place in an exclusionary, oppressive culture ends up contributing to a tragedy that might have been prevented. In one way or another, these characters particularly, along with David’s self-absorbed nihilism, contribute to Gloria’s death.

Symbolically, Hansberry points out that love and concern for other human beings is paramount. Too often, relatives, friends and cultural influences contribute to daily tragedies because human nature’s weaknesses in “missing the signs” contort such love and service to others. Ironically, politics, whose idealized mission should be to reform and make the culture more humane, decent and caring, is often hijacked by the powerful for their own agendas to produce money and more power and control. The resulting misery and every day tragedies accumulate until there is recognition, and the fight begins to overcome the malevolent, retrograde forces that O’Hara and his cronies represent.

This, Sidney vows to do with his paper and Iris’ help in a powerful speech to O’Hara proclaiming a key theme. To be alive and not spiritually, soulfully dead, one must be against the O’Haras of the world and the forces of corruption. To support them is to support death and dead things. To recognize how the power-brokers peddle death, one must discern their lies and avoid being lured into their desperate cycle of destruction, which they control to keep the populace oppressed, hopeless and suicidal.