Paris Daze (day 5) With Co-author of ‘The Haunted Guide to New Orleans’

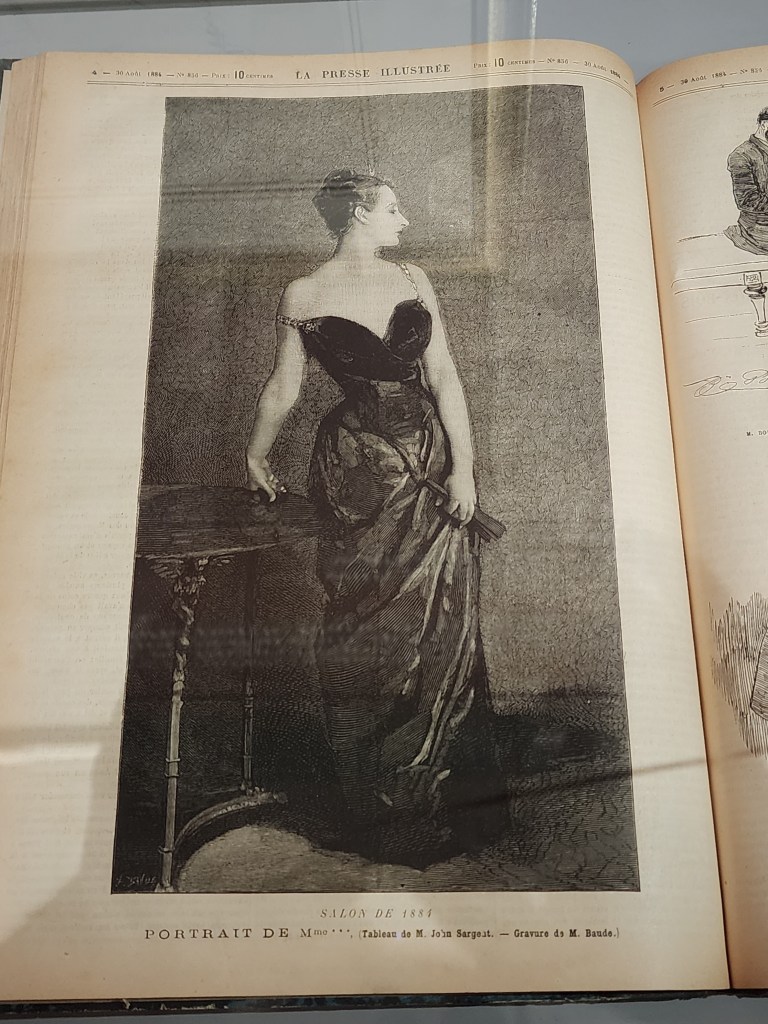

Thursday was an eventful day. First, we were off to the Musée d’Orsay to see the John Singer Sargent exhibit which was presented in partnership with the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. According to the d’Orsay, the exhibit John Singer Sargent Éblouir Paris was “organized in partnership with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for the centennial of the artist’s death.” Both exhibits take a look at Sargent’s early career. The MET ran its Sargent and Paris exhibit April 27th through August 3rd, after which arrangements were made to send over the paintings to the Musée d’Orsay. In its exhibition material, the d’Orsay states that some of the Sargent paintings are being seen for the first time in France.

Since Rory and Rosary are working on their book about John Singer Sargent and Madame X, Rory was keen to continue her research into the painter and his subject, Parisian socialite, Madame Pierre Gautreau (the Louisiana-born Virginie Amélie Avegno; 1859–1915) who was married to a wealthy Parisian banker. Unable to get to the MET exhibit, Rory who had seen the painting of Madame X before, was happy to do more extensive research in the City of Light, which was held the culture and society that produced the scandalous reaction when Sargent’s painting was presented.

Rory contacted Lucie Lachenal-Taballet, who is a research engineer at the biblioteque interuniversitaire de la Sorbonne. Her expertise is in art criticism and the press in the 19th century. Ms. Lachhenal-Taballet graciously arranged for all of us to enter one hour early and see the Sargent exhibit before the crowds arrived.

We each took our time viewing the paintings. I had seen the Sargent exhibit at the MET and noted the differences.

The d’Orsay perspective decidedly enhanced Sargent’s French influences with a selection of paintings under the tutelage of Carolus-Duran, one of his teachers in Paris. Some of these were absent from the MET exhibit. However, the MET included five paintings by other painters, Sargent contemporaries, teachers and influencers. An example is of Comtesse Potocka (Princesse Emmanuela Pignatelli di Cerchiara) painted by Léon Bonnat (1880). According to the MET description in the Sargent and Paris exhibition materials, “Bonnat was a significant and sought-after portraitist in the 1870s and 1880s, and one of Sargent’s teachers at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.”

The MET used these paintings, like the one of Comtesse Potocka (Princesse Emmanuela Pignatelli di Cerchiara) to compare them with Sargent’s Madame X. In three of the paintings at the MET exhibit, the women subjects are examples of renown Parisienne socialites of the time. Similarly, two additional paintings are entitled “The Parisienne.” The painters are Leon Bonnat, Carolus-Duran, Edouard Manet, James McNeill Whistler and Charles-Alexandre Giron. All stunningly capture the historical, cultural period in Paris, revealing fashionable wealthy women of Parisian high society.

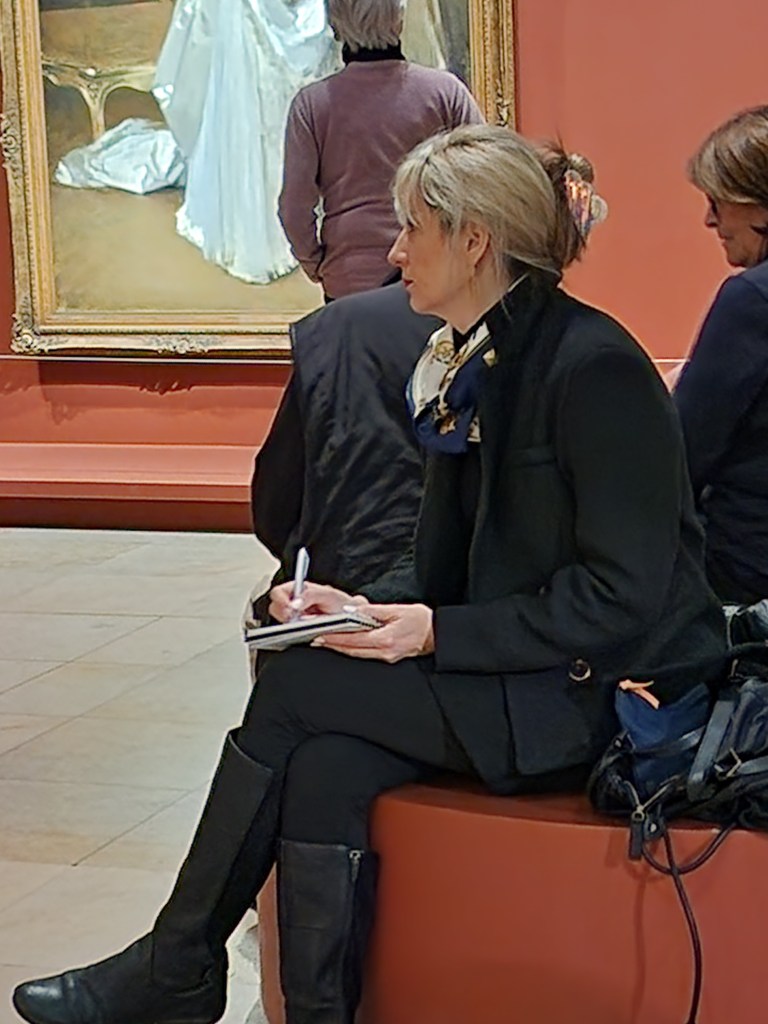

Interestingly, the d’Orsay’s exhibit didn’t include works from other painters to use as a comparison. So Rory spent time reflecting and taking notes on Sargent’s painting and various sketch studies he used in preparation for Madame X. She asked Bill and me about our impressions. When we finished with the exhibit, we headed off to other sections of the d’Orsay while Rory remained behind to study.

I looked at the Ernest Hébert paintings. (He is known for La Mal’aria in the d’Orsay collection). The exhibit included a few of his paintings of the peasants of Latium, strikingly beautiful works painted during his thirty year period in Italy.

Also, I visited the Impressionists and looked at the van Goghs on display. I’ve written a play which references a lost van Gogh. My play, yet to be produced/published, was well received by workshop mentors, classmates, a partner I collaborated with and various friends I trust to read my work and be honest without feeling they need to flatter me.

Rory continued with her research and notes, then readied herself for her appointment to interview Lucie about the exhibit, Sargent and other salient details that would be included in the book about the relationship between Sargent and Madam X. Apparently, after the painting’s presentation and the eruption of scandal, the close relationship between Madam X and Sargent fell apart. After her interview, Rory continued the rest of the day perusing the archives for any information she might find that would solidify and refine her impressions and hard information about Sargent and Madame Pierre Gautreau.

After viewing the Impressionists collection (I’ve seen the exhibit at the d’Orsay a number of times), I walked back along the Seine River to a favorite avenue in the fifth arrondissement, Boulevard Saint-Michel.

Walking up past the Sorbonne, and past the Pantheon, I arrived at the little park and environs where the TV series Emily in Paris had set-ups for various external shots.

It’s around the corner of the Irish Cultural Centre and now, has become a tourist attraction. Years ago, when I walked through theis park with its lovely water fountain, it used to be empty.

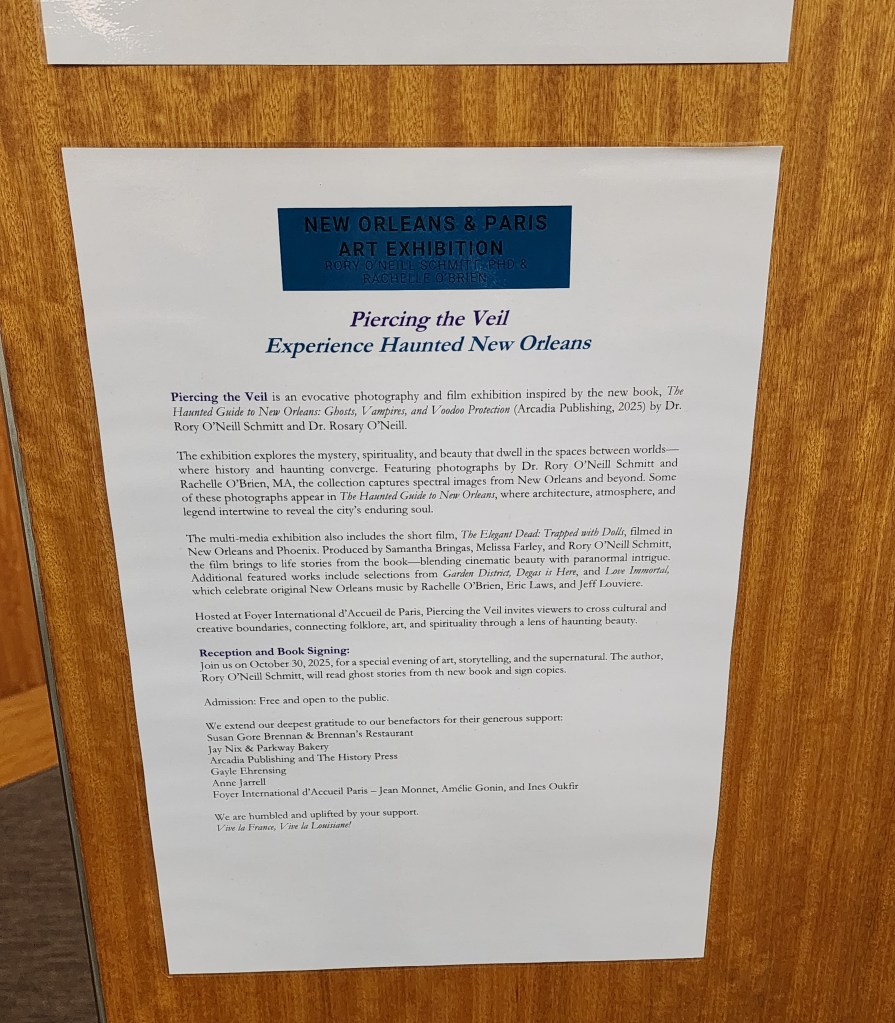

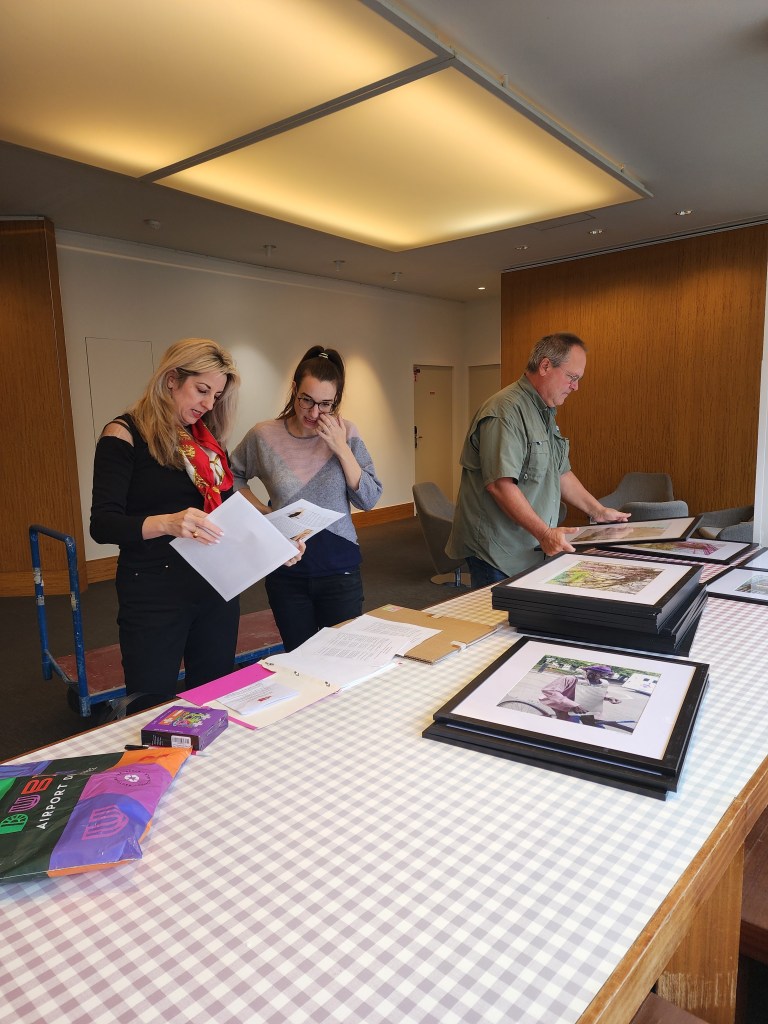

After the team reconvened back at the Irish Cultural Centre, we took a cab to Foyer International d’Accueil de Paris (FIAP), where Rory was presenting the photography exhibit ‘Piercing the Veil.’

These were the photographs Rory, Amelie and the team had put up earlier in the week. Rory and sister Rachelle took the photographs of the various haunted buildings and New Orleans environs for The Haunted Guide to New Orleans. FIAP residents got to look at the photos since Monday. Now it was time for the formal opening of the exhibit.

Amelie introduced Rory and the exhibit and then Rory continued in French, discussing the book and the photographs of New Orleans of buildings where ghosts have been sighted.

Before Rosary read from the introduction of The Haunted Guide to New Orleans, she shared some words of wisdom and humor in French gathering laughter from the crowd. Rosary, a former actress a long while ago, and a playwright in addition to her histories she’s worked on alone and with Rory is dramatic and theatrical. She can read the most boring, dull technical paper on how to set up barometric instruments for home use and make it interesting. Her reading of the book’s intro was superb.

Before, during and after the presentation, there were light bites and wine to accompany the nibbles, which added to the atmosphere of conviviality. Some of Rosary’s former friends stopped by and she spoke with them via Zoom.

A long time friend who was a liaison between France and New Orleans’ cultural affairs spoke to Rory about getting their books translated into French. Other friends were present and showed up to support Rory and Rosary’s new book release.

After Rosary’s dramatic reading there was a multi-media presentation of a short, spooky film, The Elegant Dead: Trapped With Dolls. Filmed in New Orleans and Phoenix, the film materializes the stories in the book and makes them palpable. Produced by Samantha Bringas, Melissa Farley and Rory O’Neill Schmitt, the film’s atmospheric haunting sends chills up and down one’s spine. The audience was rapt. until the end, then stayed for more conversation.

Ours was a long, fulfilling day that ended with a late dinner at a nearby restaurant that seems to always be open for everything lovely, including French onion soup, Le Comptoir du Panthéon.

Rosary and Rory Talk: ‘The Haunted Guide to New Orleans’ at the ICC, Paris Daze 3 & 4

The Irish Cultural Centre in Paris is formerly to a large collegiate community of Irish priests, seminarians and lay scholars whose origins stretch back to 1578. In its historical foundations, the website indicates that “for most of the 19th and 20th centuries the college resumed its role as seminary to Irish and Polish students.” It was converted into a hospital to accommodate three hundred French soldiers, surviving the Franco-Prussian War, and the two World Wars. Additionally, the ICC served the United States army in 1945 as a shelter for displaced persons claiming American citizenship. The Polish seminary in Paris established itself in the Collège des Irlandais in 1945. It stayed until 1997.

It has been the home of residents from Ireland and elsewhere. Some residents take classes at the Sorbonne. Others who apply may receive a residency to study, do research and write. Rory and Rosary have had a number of residencies at the Irish Cultural Centre located conveniently in the 5th arrondissement of Paris near the Sorbonne.

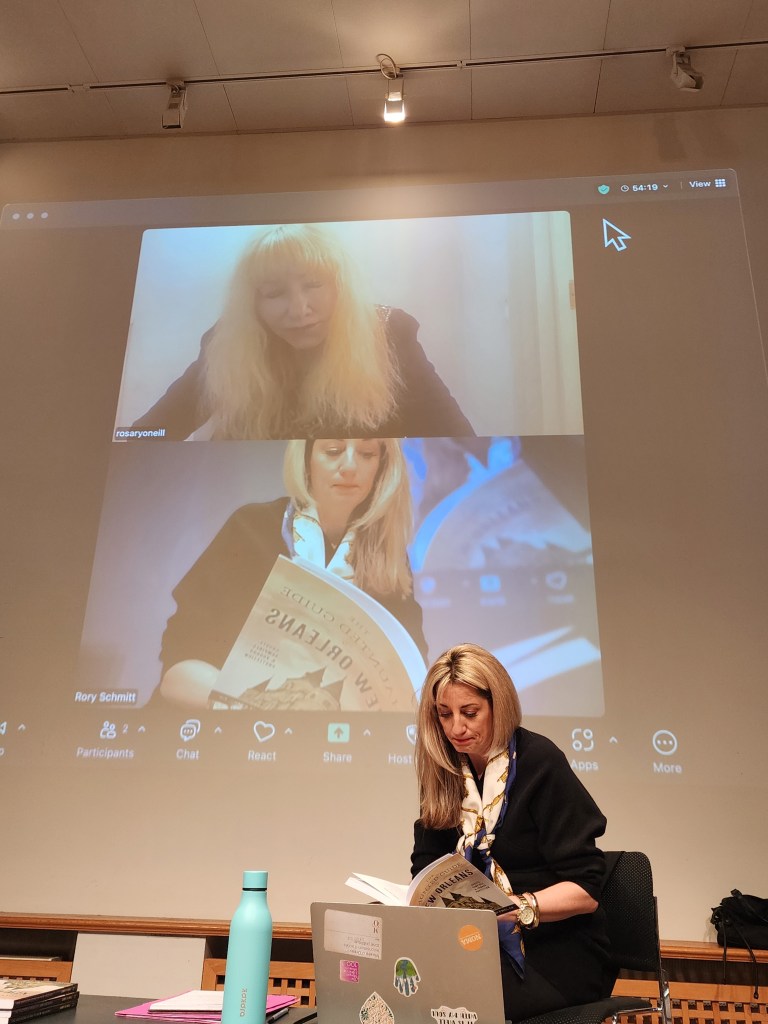

Continuing with my shadowing of Rory, Tuesday and Wednesday were busy days. Connecting via Zoom back in New Orleans, Rosary woke up in the early morning hours of darkness to convene with guests and Rory who hosted the talk about their work live from Paris. Mother and daughter are a joyful tag team. They discussed salient points about how they accomplish their research together. Oftentimes, they alternate chapters. For example after they discuss what topics they want to explore, they decide who can best illuminate the topic based on prior knowledge and interest.

Humorously, Rosary commented that she is frightened of the paranormal and would prefer not to experience any ghostly sightings. For her part Rory is thrilled about the paranormal and very much an aficionado of ghosts and all things paranormal and supernatural. She hopes to work on another book about ghosts. She thoroughly believes in being unafraid to experience the alternate realms of consciousness after individuals pass into the places beyond the veil.

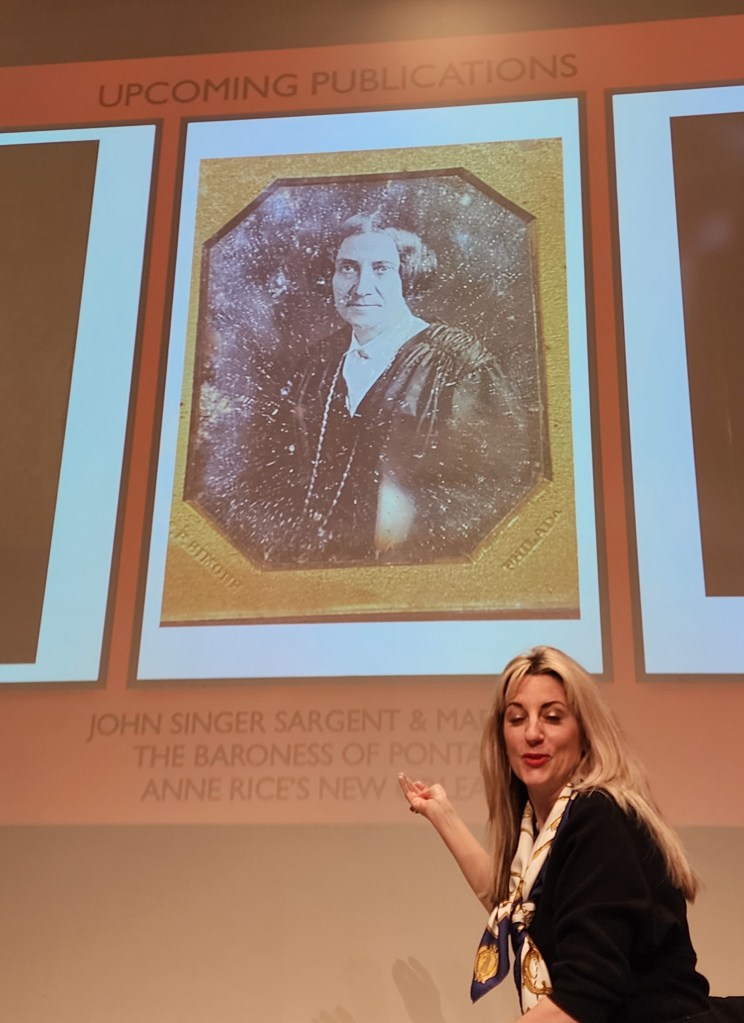

Not only did their talk reference ghostly presences in around New Orleans, some hilarious, some truly scary, they also discussed past and future projects. These, alluded to in the previous article, are coming into full bloom. One, a TV series about Edgar Degas is being worked on as mentioned. Another, the fascinating relationship between John Singer Sargent and Madame X continues to fuel Rosary and Rory’s interest as they look for the clues which lead to new insights never explored by biographers and authors before. That project is in its review stages having already been written. However, Rory has been working hard in Paris to make sure there is nothing to add to their comprehensive work.

Nevertheless, she went to two exhibits to gain more information that may lead to additional clues to spark the research questions that drive the project forward and enhance the conclusions. I’ll start with the exhibit we saw on Thursday, then backtrack to the exhibit we saw on Wednesday.

On Thursday we went to the Musée d’Orsay to see the exhibit of John Singer Sargent’s years in Paris. Of course, a main feature is his masterpiece “Madame X” which, as mentioned in the previous article, he presented to the Salon with great controversy.

Rory and Rosary researched Sargent and Madame X’s relationship extensively and nothing more might be added to what they’ve written. But I do admire Rory’s tenacity to go the extra distance to make sure she and her mom have left no stone unturned when presenting the backstory of these two individuals who made history together.

On Wednesday, Rory and I went to La place de la Concorde to investigate The Hôtel de Pontalba which has a fascinating history that relates to one of the subjects she is researching, the Baroness Pontalba. Indeed , Rory wanted to see the site where the New Orleans-born Baroness Micaela Almonester de Pontalba lived from 1855 until her death in 1874.

However, the property and environs have had a convoluted history, redevelopment and refurbishment as one would imagine since her heirs sold the property two years after her death. Supposedly, only the original gatehouse and portals were left intact, but following much of the H-shaped ground floor plan. It has been the official residence of the United States ambassador to France since 1971.

When we stopped by, the security was very heavy and we weren’t even allowed to take a picture. However, are the gatehouse and portals still present on the property? And how might this inform the story about the Baroness that Rory and Rosary would like to share? More research is needed.

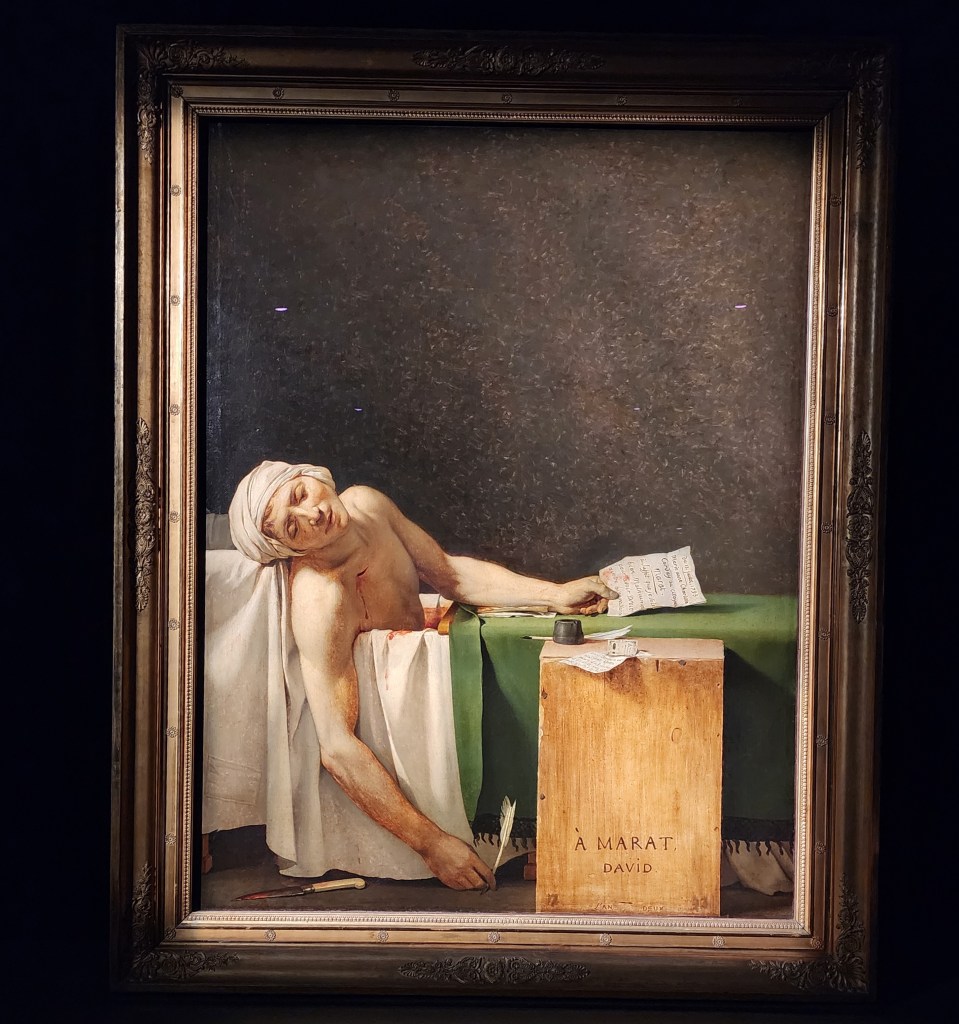

Then we went to the Louvre exhibit to enjoy the paintings of Jacques-Louis David, a French painter whose work spans the years of 1748 through 1825. The exhibit marks the bicentennial of his death in exile in Brussels in 1825. The Musée du Louvre proclaimed on its website that the exhibit “offered a new perspective on a figure and body of work of extraordinary richness and diversity.”

While I waited with Rory on the line to get into the Louvre to see the Jacques-Louis David exhibit, she explained why she wanted to see his work. Once again, she was checking for clues and looking for inspiration. Apparently, Jacques-Louis David was the teacher of his student Claude-Marie Dubufe. Dubufe painted the portraits of Micaela Pontalba (The Baroness) and Marie de Ternant (Amelie Gautreau/ Madame X’s grandmother). Micaela Pontalba and Madame X’s grandmother were contemporaries.

Certainly seeing Jacques-Louis David’s magnificent works was worth the wait. The exhibit at the Louvre looks to be one of the more popular ones. Thankfully, Rory’s scholarship and research mission allowed us an early entrance to the John Singer Sargent exhibit. Both exhibits were among the highlights of our time in Paris.

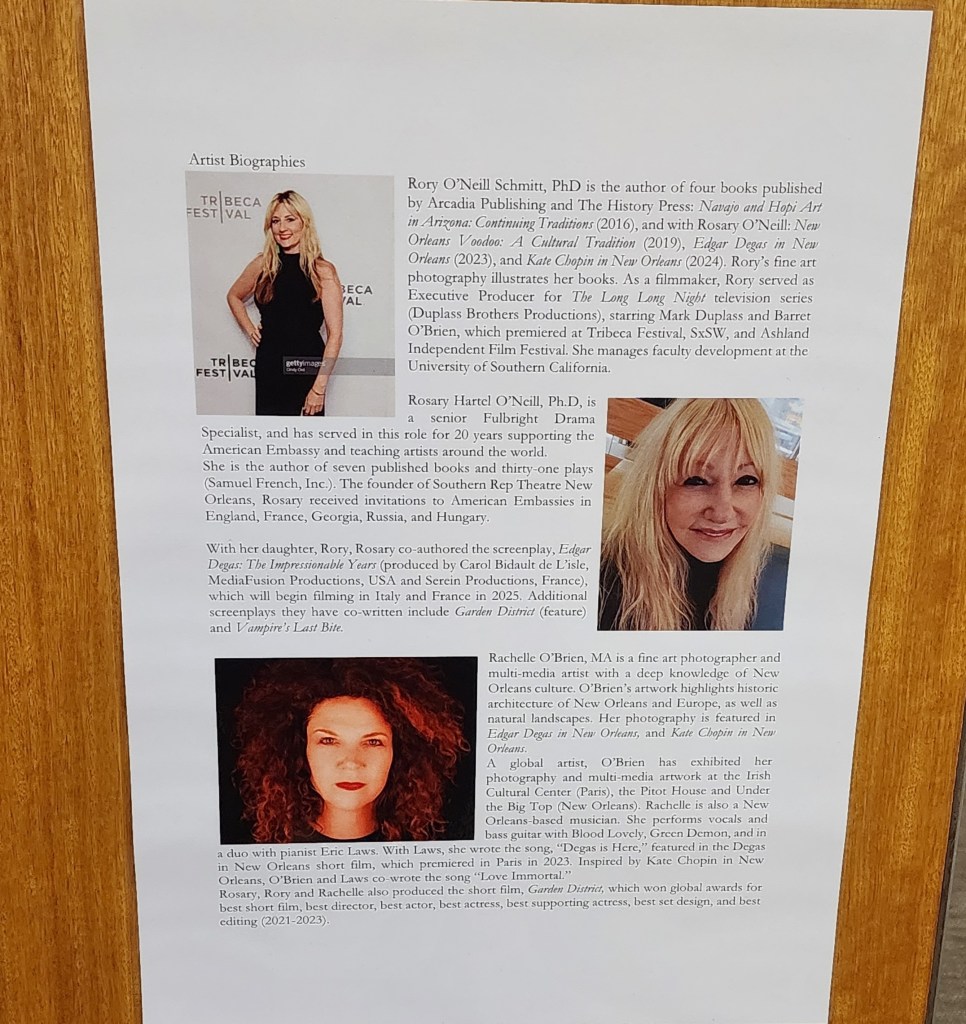

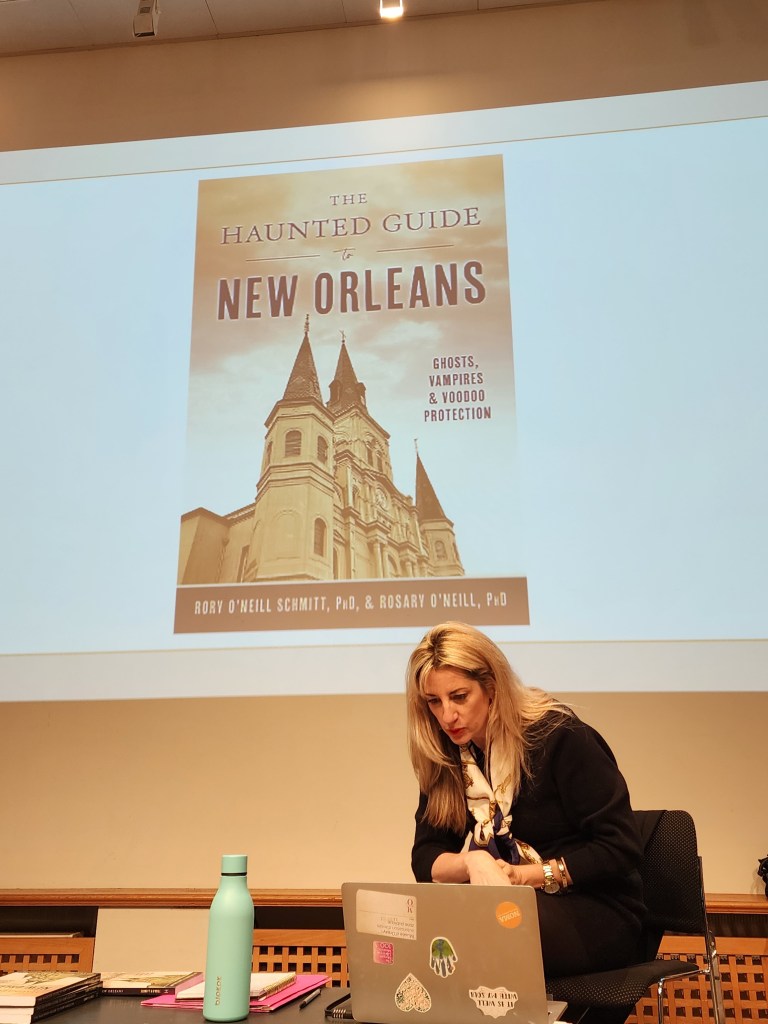

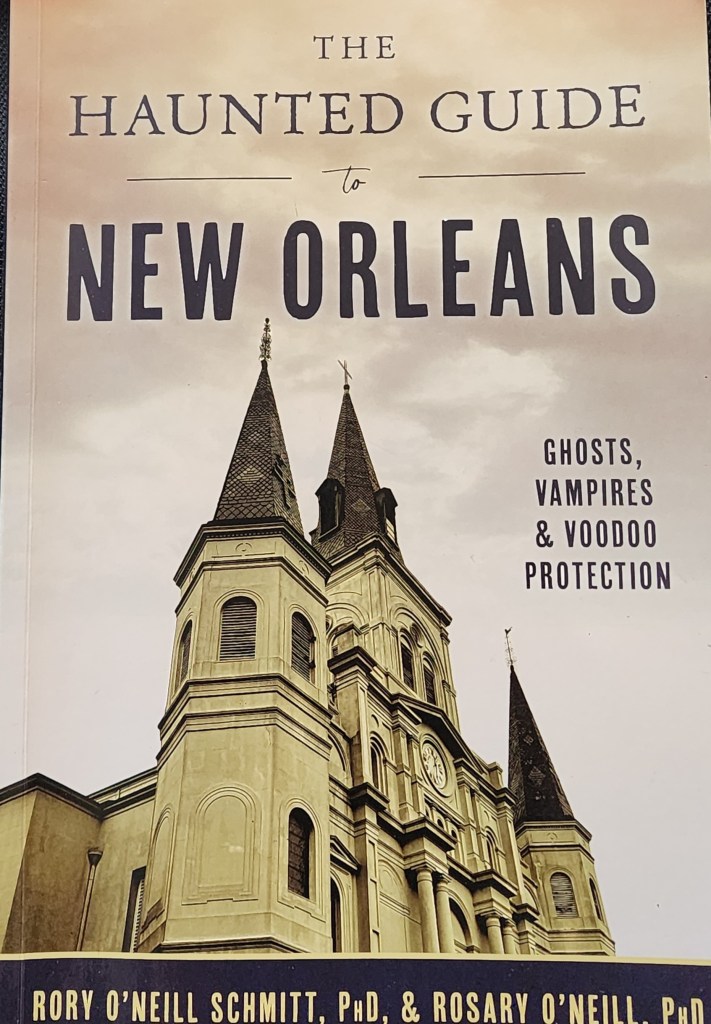

Shadowing the author of the spooky ‘Haunted Guide to New Orleans,’ Paris daze/days 1-2

Rory O’Neill Schmitt, Ph.D., the co-author of a number of books with her mother Rosary O’Neill, Ph.D. has a fascinating release which may chill you to the bone. Published by the History Press, it is The Haunted Guide to New Orleans. If you love New Orleans, and who doesn’t, you surely will love this guide. If you love or are intrigued about ghosts, the spirit realm and going beyond the veil that spiritual leaders in all religions have negotiated and broken, then this book is for you.

On every page, you will read about how the ancestor spirits of New Orleans inhabitants live among the current residents and tourists. Most of the times you don’t hear a whisper into the other consciousness of the ghostly inhabitants of NOLA. Other times, they nudge you and make their presence known, then evanesce. You think you saw or felt something, but then assure yourself that you didn’t.

Well, Rory O’Neill Schmitt and Rosary O’Neill (both possessing doctorate degrees in their own right) and I plan to dispossess you of the notion that “ghosts and spirits and haunts, oh my,” are real. And if you approach them with a respectful attitude, after all they certainly are relatives to the family of humankind, then you will accept that all of what is in another consciousness and all that is in our own consciousness and material realm join together and impact each other. Indeed, quantum physicists are proving there are many dimensions. And physicists indicate that quantum particles impact and even change particles under certain circumstances, indicating that everything is related to everything else.

This brings me to The Haunted Guide of New Orleans, and shadowing Rory O’Neill Schmitt in Paris where she is presenting her findings about New Orleans and the myriad number of places where bona fide ghostly encounters have happened and continue to happen. Also, I am shadowing her as she continues to do research on other projects that tie Paris and New Orleans.

One project of Rory and Rosary’s concerns a 6-episode Franco-Italian TV series about painter Edgar Degas with Serein Productions. The producer is Carol Bidault’l de L’Isle (seen above) who makes her home in New Orleans. The series focuses on family and the early years of the painter, which both Rosary and Rory have written about extensively (play, musical, history). Other projects they currently work on now are essentially profiles of incredible, forward thinking women, some of whom made their lives in New Orleans. One is the Baroness Pontalba (Micaela Almonester Pontalba of New Orleans). The other fascinating woman caused an absolute scandal. She is Amélie Gautreau of New Orleans.

Of course if you are not from New Orleans or are not familiar with the painter associated with Amélie Gautreau, you won’t recognize her name. However, the famous John Singer Sargent who did numerous sketches and studies of Amélie Gautreau before he finalized his oils of her and presented her in the Paris salon as Madame X, never imagined the extent to which he and she would be party to a scandal when the painting was unveiled to polite society. His painting was considered indecent, and demands for it to be altered and taken down created an ironic furor. Today, celebrities welcome such controversy because nowadays, controversy sells. Sargent and Ms. Gautreau were not looking for publicity, but it found them.

So back to the Paris – New Orleans connections. I’ve been shadowing Rory, as unfortunately, her mom Rosary wasn’t able to make the trip this time. What follows in this article and others is a compendium of the days in Paris that Rory spent getting ready for her presentations and following up on her research connected with her projects. What a delight this working trip has been thus far.

As a group of us walked home, we enjoyed Paris before nightfall right around the surreal time of sundown. Paris is even more amazing at dusk. How many spirits are haunting this magical city? Too many to account for, perhaps.

‘The Other Americans,’ John Leguizamo’s Brilliant Play Targeting the American Dream Extends Multiple Times

After a long career in every entertainment venue from films, to TV, to theater, Broadway, Off Broadway, etc., the prodigious work by the exceptional John Leguizamo speaks for itself. Now, Leguizamo tackles the longer theatrical form in writing The Other Americans, extended again until October 24th at the Public Theater.

Superbly directed by Ruben Santiago-Hudson, the theatrical elements of set design, lighting, costumes speak to the 1990s setting and cultural nuances. The following creatives developed a smart, stylish representation of the Castro household (Arnulfo Maldonado-set design, Kara Harmon-costumes, Justin Ellington-sound, Lorna Ventura-choreography).

Perhaps Leguizamo’s play could be tweaked to tighten the dialogue. All the more to have it shine with blinding, unforgettable truths sounding the alarm for immigrants in this nation. If tightened a bit, the complex, profound play would land perfectly as the unmistakable tragedy it inherently is. However, in its current iteration, Leguizamo gets the job done. The powerful play with comedic elements resonates to our inner core as a nation of immigrants and especially for Latinos.

Clearly, Leguizamo’s characterizations and themes add to the canon of classics that excoriate and expose the corrupted myth of the American Dream as a lie fitted to destroy anyone who believes it. That immigrants make the sacrifices they do to embrace it, is the ultimate tragedy.

Nelson Castro (played exquisitely by John Leguizamo), born in Jackson Heights from Columbian ancestry, embraces the American Dream. His wife Patti (the amazing Luna Laren Velez), from her Puerto Rican heritage, not so much. Patti’s values lead to loving her family and friends with devotion. Daughter, Toni (Rebecca Jimenez), who will marry the solid but nerdy Eddie (Bradley James Tejeda), looks to fit in as a white woman. The younger Nick (Trey Santiago-Hudson) was like his dad and took advantage of others, fiercely competitive. However, an incident changed him forever.

As the play unfolds, Leguizamo deals with the central question. To what extent have the warped values of the predominant culture negatively impacted this Latino family? From his first speech on we note that these twisted values have lured Nelson. The ethos-scam to get ahead-guides Nelson like a veritable North Star. He uses “getting over” as the key reason to provide for his family. This excuse rots everything under his power.

For example, Nelson acts the part of the upwardly mobile success story who always has a deal on the table ready to go. The irony is not lost on us when Nelson hypes a deal with a real estate big wig. Meanwhile, the mogul lives off his reputation for ripping off minorities. Sadly, Nelson admires the mogul’s pluck and con abilities. He ignores how this can potentially harms Latinos.

Mirroring the sick culture and society that values money and material prosperity over people, Leguizamo’s tragic hero tries to wheel and deal to get ahead. Making bad decisions, he overextends himself. Meanwhile, he encourages Nick and Toni to follow his lead. His overweening pride as the patriarch drives him to assume the mantle of a power player. Indeed, the opposite is true. During the process that causes him to fail and lie about it, he compromises his integrity and family’s probity and sanctity. That he willfully blinds himself to the consequences of his beliefs and suppresses his intelligence and good will to fit in, is the final heart breaker.

As in the classic tragic hero, Nelson’s pride also dupes him into a psychotic circularity to believe he has no recourse. Of course he believes the wheels have been set in motion against him by the society’s bigotry and discriminatory values. He should recognize and reject the society that uplifts such values because they support doing whatever necessitates getting ahead. The entire rapacious structure promotes financial terrorism and, whenever possible, it must be rejected. However, Nelson can’t reject it because he can’t help himself from being seduced. Instead, he persists in a prison of his own making, digging his family grave, on a collusion course of self-destruction.

Sadly, he internalizes the society’s inhumanity and makes it his own, a self-hating Latino. Because he adopts this construct because he loathes his immigrant self, he tries to create a new identity apart from his inferior ancestry. Thus, he moves to Forest Hills away from Jackson Heights where he lived “like an immigrant” in a place where cockroaches multiplied.

Finally, as we watch Nelson struggle to assert this new identity in a flawed, indecent, racially institutionalized culture (represented by Forest Hills and what a group of kids did to his son in high school), Leguizamo’s play asserts an important truth for immigrants. Internalizing and adopting the culture’s corrupt, sick, anti-human values is not worthy of immigrants’ sacrifices. This theme is at the heart of Leguizamo’s play. In his plot development and characterizations Leguizamo reveals his tragic hero chases after prosperity and upward mobility. The incalculable loss of what results-losing what it means to be human-isn’t worth it. If one does not weep for Leguizamo’s Nelson at the play’s conclusion, you weren’t paying attention.

To exemplify his themes, Leguizamo uses the scenario of the Castros, an American Latino family. They move from the homey, culturally diverse Jackson Heights to the white, Jewish upscale, racist enclave of Forest Hills. At the outset of the play Nelson, a laundromat owner, awaits his son’s return from a psychiatric facility. Patti has cooked up her son’s favorite dishes. Not only does this reveal her care and concern for her son, her comments to Nelson show her nostalgia for the Latin foods and people of their original Jackson Heights neighborhood in Queens.

By degrees Leguizamo reveals the mystery why Nick was in a facility. Additionally, the playwright brilliantly explores the conflicts at the heart of this family whose parents put their stake in their children, chiefly son Nick to get ahead financially in the Castro business. To recuperate, the doctors partially helped Nick with medication and therapies.

However, on his return home months later, he still suffers and has episodes. Patti sees the change in his dislike of his old favorite foods (symbolic). Not only does he reject meat, he rejects Catholicism and turns to Buddhism. Because a girl he met at the facility influences him, he moves away from his Latin roots. Later, we learn he loves and admires her and they plan to live together. However, he doesn’t look at the difficulties of this dream: no money, no family support.

The family conflicts explode when Nick attempts to be truthful with his parents. In his conversation with his mother we learn the horrific details of the beating he received in high school, why it happened, and how it led to episodes in college. Wanting to move beyond this through understanding, Nick learns in therapy that he must talk to his father. Nelson refuses to acknowledge what happened, and becomes a stalemate to Nick’s progress.

Additionally, his doctor supports Nick’s getting out from under the family’s living arrangements. Inspired, Nick yearns to create a life for himself away from their control to be his own person. Ironically, he follows in his father’s footsteps wanting to create a new identify for himself. Yet, he can’t create this identity unless he confronts the truth of what happened to him in high school and talks to his father. Unless he understands the extremely complex issues at the heart of his father’s tragedy, they won’t move forward together. Nelson must understand that he hates his own immigrant being and has embraced sick, twisted corrupt values which he never should have pushed on his family.

Meanwhile, in a fight with Nelson, Nick demonstrates what may really be happening to him. Though he survived the high school beating with a baseball bat, he most probably suffers from what doctors have come to understand as TBI (traumatic brain injury). With TBI the individual suffers debilities both physically and emotionally. When Nelson questions the efficacy of the treatment Nick received from doctors who didn’t really know what was happening to Nick, Nelson is on the right track. But the science had to catch up to Nelson’s observations.

Meanwhile, the problems relating to Nick needing the right help from his parents and his doctors, Nelson’s financial doom and the future of this Latino family under duress are answered in a devastating, powerful conclusion.

There is no spoiler. Leguizamo elegantly and shockingly reveals this family as a microcosm of the ills of our culture and society. Additionally, he sounds the warning for immigrants. If they don’t recognize and refuse the twisted folkways of the “American Dream,” they may lose their self-worth and humanity for a for a lie.

The Other Americans runs 2 hours 15 minutes including an intermission at The Publica Theater until November 23, 2025. https://publictheater.org/theotheramericans

‘Is This Thing On’ Bradley Cooper’s Third film @63rd NYFF

Comedy and tragedy masks couple side by side for a reason. Bradley Cooper’s third (A Star is Born, Maestro) directorial outing, Is This Thing On?, adds meaning to the notion that misery loves comedy. Will Arnett and Laura Dern play a couple whose separation leads to catharsis and regeneration when Alex turns to comedy to lighten his soul’s unhappiness. Is This Thing On? a World Premiere in the Main Slate section of the 63rd New York Film Festival, screened as the festival closing night film.

Cooper incisively shepherds the intimate and naturalistic performances of Will Arnett (Alex) and Laura Dern (Tessa). The actors portray a long-time married couple. In the opening film scene both agree without fireworks and fanfare (while Tessa brushes her teeth) to call “it” (their marriage thing) off.

Throwing the typical divorce sequences out the window, Cooper skips to the aftermath of the separation and Alex and Tessa’s amicability. First, they split custody of their two 10-year-old sons, played with sharp comedic timing by Blake Kane and Calvin Knegten. Secondly, after the opening shot of agreeing about “it,” we note by the next time they get together with their couple friends (Andra Day & Cooper, Sean Hayes & Scott Icenogle) Alex moved into an apartment in New York City. Meanwhile, Tessa remains in their house with their playful Labradoodles and sorrowful sons who comment that their parents argued a lot.

One evening instead of going home to his empty, lonely apartment after seeing Tessa and friends, Alex saves a few bucks cover charge by adding his name to the open mic list of a basement comedy club (The Comedy Cellar). As a possible joke on himself, Alex sheepishly takes the mic. However, when he spontaneously, unabashedly, surprisingly vomits out personal information about his marriage, a lot of it morose, some of it funny, the last thing the self-loathing Alex imagines, then happens. He gets a few laughs and lots of encouragement from the crowd of wannabe comedians.

In a fantastic twist, Cooper cast many of these real-life comics as audience members. Their authentic jumble of responses picked up by sound designers works to create the naturalistic environment where Alex slowly recharges his deadened mojo.

A guy can get used to this shot of adrenaline to stave off his soul’s sickness. Maybe if he returns a few times, he can reveal to himself what the hell happened emotionally and psychically that caused him to end up alone, without his wife and kids on the doomed path to divorce. If expiation indeed softens a crusty-edged, hardened, sad sack, perhaps more spilling of his guts will be the medicine he needs to ameliorate the hell within.

Thus, the initial few laughs and non judgmental camaraderie of fellow comic wannabes trigger Alex to return for another open mic night. And once more, Alex’s self-abasing confessions to himself and the crowd magically lift his spirits. Alex’s serendipitous impulse not to take his inner angst to heart blossoms. As he evolves his comedic timing and content, he resolves he can become a better person through confessional stand-up comedy. There’s nothing like getting in touch with one’s inner hell via artful performance, where self-reflection brings about self-correction.

Alternating scenes, Alex’s new revelatory jokes at the comedy club, with Tessa and friends meet-ups, we note the gradual change in Alex’ emotions and moods. Even his friend Balls (Cooper in a funny, facially hirsute turn), tells him that maybe he will divorce his wife (the beautiful Andra Day) following Alex’s route, because he seems happier unmarried.

This revolutionary way to deal with divorce among a community of comics really happened to British stand up comedian John Bishop. The true events inspired the script by Cooper, Arnett and Mark Chappell with some of the uneven dialogue prompted by extemporaneous ad libs by the cast.

Interestingly, Alex’s wayward jokes that don’t land had to be worked on by Will Arnett and Cooper. In a Q and A after the screening Cooper grinned when he said that Arnett’s humor out-shined Alex’s and had to be tamped down. Thus, the jokes never flow seamlessly like a professional’s patter since Alex must find his way through trial and error. Likewise, Alex and Tessa’s relationship which took a hairpin turn with their break up, takes another when Tessa goes on a friend/date (with Peyton Manning) in a cute set-up for the possibility of her first sexual encounter after the split.

Where do they show up? At the comedy club where Alex hits a new high/low discussing his first sexual encounter after his break-up. What did he learn from the sex? He tells the audience in a heartfelt moment he missed his wife. Pleasantly surprised and turned on to hear that Alex missed her, Tessa confronts Alex about his “letting it all hang out” riff at the club. Though Tessa’s appearance at the club with her date smacks of contrivance, the coincidence is delicious for the next plot twist. This hearkens back to the film’s title. Finding their attraction to each other rekindled, do they or don’t they get back together? When and where the answer arrives adds hilarity to their tenuous situation.

Importantly, their dead-ended relationship moved off its axis opening up new possibilities. Finally, they communicate their feelings beyond arguing. And just as Alex has found a new trajectory and hope with his comedy club appearances, Tessa returns to her love of volleyball as a former Olympic player, sharing her skills and expertise as a professional coach.

Meanwhile, Alex’s parents (Christine Ebersole and Ciarán Hinds) weigh in with their opinions, though they refuse to choose sides to keep the peace. In targeting the complexity of human relationships, Cooper shows the difficulties in letting go of an old, tired relationship stuck in destructive grooves. Also, he mines the ground of rebuilding a relationship and setting it in another positive direction. With that reconstruction also comes the rebuilding of identity and self-worth if they couple uses the opportunity of a break to begin a renewal.

Dern and Arnett are terrific surrounded by a great supporting cast. These include the actors mentioned above and additionally Amy Sedaris and New York stand up standbys for example Reggie Conquest, Jordan Jensen, Chlore Radcliffe. These comedians help to make the film a love letter to New York and its downtown scene.

For the description of Is This Thing On? at the 63rd NYFF go to their website. https://www.filmlinc.org/nyff/films/is-this-thing-on/ The film will be released December 19th.

Keanu Reeves, Alex Winter carry Ted and Bill into the adventure of ‘Waiting for Godot’

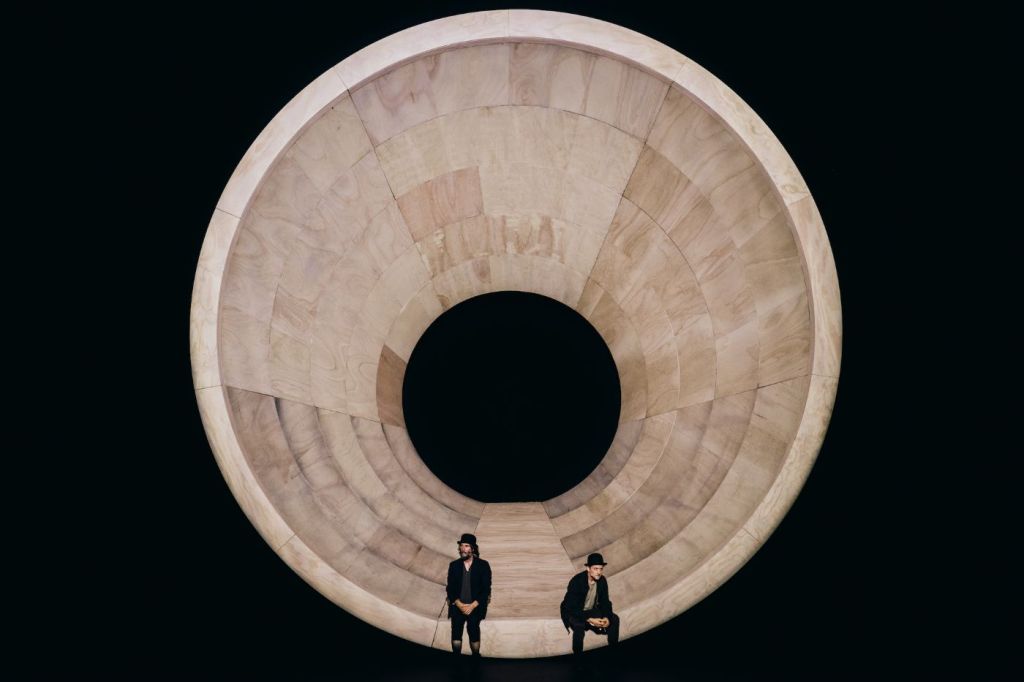

Referencing the past with Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure movie series, something has happened. Bill (Alex Winter) and Ted (Keanu Reeves), who long dropped their younger selves and reached maturity in Bill and Ted Face the Music (2020), have accomplished the extraordinary. They’ve fast forwarded to a place they’ve never been before in any of their adventures. An existential oblivion of uncertainty, Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

There, they cavort and wallow in a hollowed out, megaphone-shaped, wind-tunnel (Soutra Gilmore’s clever set design). The gaping maw is starkly, thematically lighted by Jon Clark. Ben & Max Ringham’s sound design resonates the emptiness of the hollow which Winter’s Valdimir and Reeves Estragon fill up to the brim with their presence. And, among other things, Estragon loudly snacks on invisible turnips and carrots, and some chicken bones.

Oh, and a few others careen into their empty hellscape. One is a pompous, bullish, land-owning oligarch with a sometime southern accent, whose name, Pozzo, means oil well in Italian (a superb Brandon J. Dirden in a sardonic casting choice). And then there is his slave, for all oligarchs must have slaves to lord over, mustn’t they? Pozzo’s DEI slave in a wheelchair, seems misnamed Lucky (the fine Michael Patrick Thornton).

However, before these former likenesses of their former selves show up and startle the down-on-their luck Vladimir and Estragon, the two stars of oblivion wait for something, anything to happen. Maybe the dude Godot, who they have an arrangement with, will show up on stage at the Hudson Theatre. Maybe not. At the end of Act I he sends an angelic looking Boy to tell them he will be there tomorrow. A silent echo perhaps rings in the stillness of the oblivion where the hapless tramps abide.

Despite the strangeness of it all, one thing is certain. Bill and Ted are together again for another adventure that promises to be like no other. First, they’ve landed on Broadway, dressed as hobos in bowler hats playing clowns for us, who happily watch and wait for Godot with them. And it doesn’t matter whether they tear it up or tear it down. The excellent novelty of these two appearing live as Didi (Vladimir) and Gogo (Estragon), another dimension of Bill and Ted, illuminates Beckett.

Keanu Reeves’ idea to have another version of their beloved characters confront Samuel Beckett’s tragicomical questions in Waiting for Godot seems an anointed choice. It is the next step for these bros to “party on,” albeit with unsure results. However, they do well fumfering around in this hollowed out world, a setting with no material objects. The director has removed the tree, the whip, or any props. Thus, we concentrate on their words. Between their riffs of despair, melancholy, hopelessness and trauma, they have playful fun, considering the existential value of life. Like all of us, if they knew what circumstances meant in the overall arc of their lives, they wouldn’t be so lost.

Director Jamie Lloyd, unlike previous outings (A Doll’s House, Sunset Boulevard), keeps Beckett’s script without alteration. Why not? Rhythmic, poetic, terse, seemingly repetitive and excessively opaque, in their own right, the spoken words ring out, regardless of who speaks them. That the characters of Bill and Ted are subsumed by Beckett’s Didi and Gogo makes complete sense.

What would they or anyone do if there was no intervention or salvation as occurs fancifully in the Bill and Ted adventure series? They’d be waiting for salvation, foiled and hopeless about the emptiness and uselessness of existence without definition. Indeed, politically isn’t that what some in a nation of unwitting, passively oppressed do? Hope for salvation by a greater “someone,” when the only possibility is self-defined, self-salvation? How long does it take to realize no one is coming to help? Maybe if they help themselves, Godot will join in the work of helping them find their own way out of oblivion. But just like the politically passive who do nothing, the same situation occurs here. Godot is delayed. Didi and Gogo do nothing but play a waiting game.

From another perspective eventually unlike political passives they compel themselves to act. And these acts they accomplish with excellent abandon. They have fun.

And so do we watching, listening, wondering and waiting with them. Their feelings within a humorous dynamic unfold in no particular direction with a wide breadth of expression. Sometimes they want to hang themselves to end the frustration. Sometimes, bored, they engage in swordplay with words. Sometimes they rage. Through it all they have each other. And despite wanting to separate and go their own ways, they do find each other comforting. After all, that’s what friends are for in Jamie Lloyd’s anything is probable Waiting for Godot.

In Act I they are tentative, searching their memories for where they are and if they are. Continually, they circle the truth, considering where the one is who said they were coming. However, the situation differs in Act II because the Boy gave them the message about Godot.

In Act II they cut loose: chest bump, run up and down their circular environs like gyrating skateboarders seamlessly navigating curvilinear walls. By then, the oblivion becomes familiar ground. They relax because they can relax, accustomed to the territory. And we spirits out there in the dark, who watch them, become their familiar counterparts, too. Maybe it’s good that Godot isn’t coming, yet. They may as well while away the time. Air guitar anyone? Yes, please. Reality is what we make it. Above all, we shouldn’t take ourselves too seriously. In the second act they don’t. After all, they could turn out like Pozzo and Lucky. So they do have fun while the sun shines, until they don’t and return right back to square one: they wait.

As for Pozzo and Lucky a further decline happens. In Act I Lucky gave a long, unintelligible speech that sounded full of meaning. In Act II Lucky is mute. Pozzo, becomes blind and halt, dependent upon Lucky to move. He reveals his spiritual and physical misery and haplessness by crying out for help. On the one hand, the oppressor caves in on himself via the oppression of his own flesh. On the other hand, he still exploits Lucky whom he leads, however awkwardly. The last shreds of his bellicosity and enslavement of Lucky hang by a thread.

Pozzo has become only a bit less debilitated than Lucky, whereas before, his identity commanded. Fortunately for Pozzo Lucky doesn’t revolt and leave him or stop obeying him. Instead, he takes the role of the passive one, while Pozzo still acts the aggressor, as enfeebled as he is. The condition happened in the twinkling of an eye with no explanation. Ironically, his circumstances have blown most of the bully out of him and reduced him to a pitiable wretch.

Nevertheless, Didi and Gogo acknowledge Pozzo and Lucky’s changes with little more than offhanded comments. What them worry? Their life-giving miracle happened. They have each other. It’s a congenial, permanent arrangement. After that, when the Boy shows up to tell them the “bad” news, that Godot has been delayed, yet again, and maybe will be there tomorrow, it’s OK. There’s no “sound and fury” as there is in Macbeth’s speech about “tomorrows.” We and they know that they will persist and deliver themselves and each other into their next clown show, tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.

If one rejects the comparison of this version of Waiting for Godot with others they may have seen, that wisdom will yield results. To my thinking comparing versions takes the delight out of the work. The genius of Beckett is that his words/dialogue and characters stand on their own, made alive by the personalities of the actors and their choices. I’ve enjoyed actors take up this great work and turn themselves upside down into clown princes. Reeves and Winter have an affinity and humility for this uptake. And Lloyd lets them play, as he damn well should.

In the enjoyment and appreciation of their antics, the themes arrive. I’ve seen greater and lesser lights in these roles. Unfortunately, I allowed their personalities and their gravitas to distract me and take up too much space, crowding out my delight. In allowing Waiting for Godot to settle into fantastic farce, Lloyd and the exceptional cast tease out greater truths. These include the indomitably of friendship; the importance of fun; the tediousness of not being able to get out of one’s own way; the uselessness of self-victimizing complaint; the vitality and empowerment of self-deliverance, and the frustration of certain uncertainty.

Waiting for Godot runs approximately two hours five minutes with one intermission, through Jan. 4 at the Hudson Theatre. godotbroadway.com.

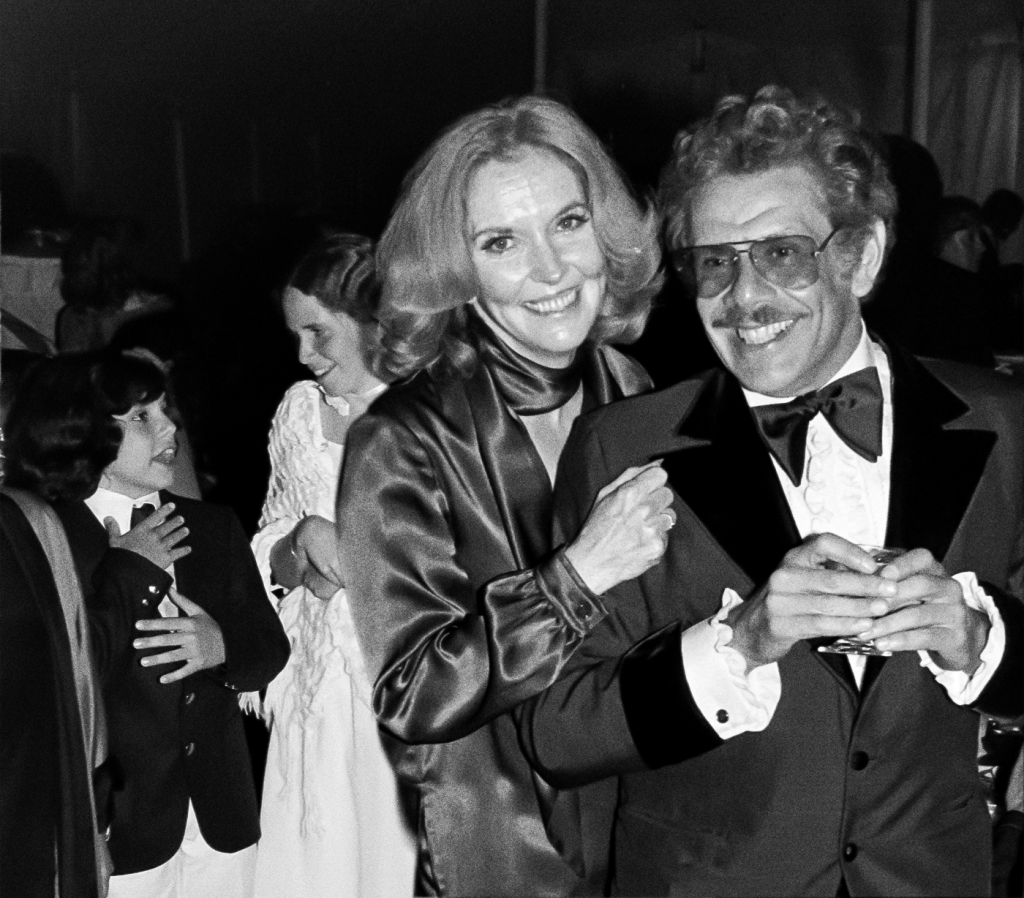

‘Stiller & Meara: Nothing is Lost’ Ben Stiller Honors his Parents’ Legacy @NYFF

In the Q and A after the screening of his documentary about his parents, Ben Stiller quipped “…my parents who couldn’t be here, I hope they’re OK with it. There’s no way to really check on that. I hope the projector doesn’t break.” Well, the projector didn’t break and no rumbling of thunder, falling lights or crashing symbols happened. So, they must be “OK” with the film. Certainly, the audience showed their pleasure with long applause and cheers. In one section near me they gave a standing ovation for Stiller & Meara: Nothing is Lost.

Ben and Amy Stiller’s film collaboration about their parents, directed by Ben Stiller, screened in its World Premiere in the Spotlight section of the 63rd NYFF. Employing their experience in the entertainment industry, Ben Stiller (comedian, actor, writer, director, producer) and sister Amy Stiller (comedian, actress) explore their parents’ impact on each others’ lives and careers to then influence their children’s lives. In the latter part of the film we note this multigenerational family project also includes Stiller’s wife, Christine Taylor Stiller; and his children Ella and Quinlin Stiller.

However, in order to begin to tell the story of three generations of Stillers, the siblings reach back before their parents’ marriage and their births. From that vantage point they first examine how Jerry Stiller and Anne Meara met. Then they explore how Jerry and Anne shared their interests and talents. Recognizing that they could work together, they created the successful comedy duo that Ed Sullivan first invited on his show in April of 1963.

Enamored of them as performers and people because their ethnic and religious backgrounds mirrored Sullivan and his wife’s, Stiller and Meara returned to the show again and again. Because they were funny and made their comedy relationship/marriage sparkle, they were a hit. In reflecting on this, Stiller shows a number of clips from the archives and even meets with Steven Colbert at the theater named for Ed Sullivan (the Ed Sullivan Theater in New York City). The two of them discuss what it must have been like to audition live as unknowns and hit the ground running on a nationally aired program that millions watched every week.

Using clips from that show, and other TV shows, films, theater and more, Stiller cobbles together a delightful, honest, intimate and funny chronicle of his parent’s marriage on and off camera. The director delves into their unique styles and talents which gave them their comedy act. Stiller insists that his dad struggled to be funny and constantly had to work at it. On the other hand his mom found humor naturally and could “ad lib” humorous riffs effortlessly. His dad so admired this about her talent.

Importantly, Stiller captures the history of that time which contributes to our understanding of the nation’s social fabric. Their work historically reflected 60s humor that appealed then but still has an appeal today. Though they worked together and refined their act for years, eventually, they worked separately. Stiller discusses how and why this happened. Essentially because they wanted different things and were their own people, they tried their own TV shows. Then other opportunities came their way.

Humorously, his documentary reflects his parents’ relationship so it became difficult to know when the comedy act ended and where their real marriage began. Perhaps it was a combination of all and/or both. Since his Dad saved tons of memorabilia (photos, programs, reviews, clips, tapes, videos, home movies) from their lives, Ben makes good use of these artifacts.

Additionally, Stiller reveals the more personal and intimate aspects of himself and Amy growing up with his parents. Principally, he uses this perspective to show the parallels with his parents’ relationship as he briefly looks at his marriage with his wife and relationship with his children. One segment has interviews with Christine, Ella and Quin. Importantly, he relates their perceptions with his attitude toward his parents growing up.

This project that began after Jerry Stiller died in 2020 and took five years to complete saw Stiller and his wife Christine through a separation and getting back together again. Stiller looked at how his parents kept their marriage together through the pressures of performing together. That reflection influenced him in his relationship with Christine.

As Stiller worked on selecting how to approach the film with the material left to him and his sister, a concept came to him about legacy. Indeed, the documentary forms a portrait of a family whose legacy of humor, creativity and prodigious hard work has passed down from generation to generation.

In short the film reveals that Stiller and his sister Amy are humorous acorns that don’t fall far from their ironic and funny parental oaks. Amy and Ben’s sharp wit from his mom and dogged perfectionism from his Dad, come into play in the creation of this film. Mindful that all of his family’s lives are in his hands, with poetic consideration Stiller’s profile of those most dear to him is heartfelt, balanced and emblematic of a gentler, loving, kinder time. We need to see examples of this more than ever. To read up on the film description and to see additional photos, go to the NYFF website. https://www.filmlinc.org/nyff/films/stiller-meara/

An Apple Original Films release, look for Stiller & Meara: Nothing is Lost in select theaters on October 17, 2025. It receives wide release on October 24th.

Jodie Foster? C’est Magnifique in ‘A Private Life’ @NYFF

In its New York City premiere in the Spotlight section of the New York Film Festival, Jodie Foster speaks French in her starring role in A Private Life. Having spoken French as a child, Foster planned to act an entire role in French for years. She finally found the right vehicle in director Rebecca Zlotowski’s capricious, ironically funny murder mystery, which also is a character study.

Foster portrays Dr. Lilian Steiner, a neurotic American psychoanalyst in Paris, whose compartmentalized, controlled life takes a weird turn. This occurs after she discovers her patient Paula (Virginie Efira), who gives no signs of severe depression or psychosis, commits suicide. Indeed, Foster’s character believes she couldn’t have misdiagnosed her, so she questions what happened.

Events cascade into chaos when Foster’s Steiner refuses to accept the suicide determination of Paula’s death and believes someone, possibly Paula’s husband or daughter, killed her. When she attends Paula’s memorial service, invited by daughter Valerie (Luàna Bajrami), Paula’s husband Simon (Mathieu Amalric), angrily evicts her from Paula’s funeral. Simon blames her for over-medicating Paula and pushing her over the edge.

His furious response to her as a terrible therapist liable for his wife’s depression and suicide dovetails with another patient’s angry response to her. The other patient claims that her expensive treatment to help him stop smoking over the years didn’t work. Instead, he engages holistic therapy, a hypnotist, Jessica Grangé (Sophie Guillemin). She helps him stop smoking in record time. Not only does he fire Dr. Steiner, eventually, he files a lawsuit against her to recoup his thousands of dollars that he spent in useless therapy sessions.

To add insult to injury that her professional career has seen better days, we discover her personal life’s problems in a reversal: physician heal thyself before you practice therapy. Divorced (she couldn’t hold her marriage together with ex-husband Gabriel [Daniel Auteuil]), Lilian visits her grown son to bond with her recently born grandson. First, Julian (Vincent Lacoste), who doesn’t seem pleased to see her, warns her not to wake the baby. Then, when he does wake, she claims she has a cold. After all, she doesn’t want to hold him and make him sick. So a potentially warm visit turns “cold” and blows up in their faces, annoying Julian.

We note Lilian’s aloofness even spills out onto her ex husband Gabriel, an ophthalmologist she drops in on because her eyes tear uncontrollably. When he pronounces that the examination shows no issues with her eyesight, we understand his care and concern for her. They remain friends probably because of Julian. However, he can’t help her unmistakable tearing up and crying.

Thus, perhaps out of initial curiosity, she seeks out her former patient’s hypnotist to get relief for her “crying.” That she seeks out the unscientific approach of a regression therapist to stop her teary eyes makes little sense. Have upsetting events (Paula’s suicide, Simon’s rage and her other patient’s fury), triggered Lilian? Rather than to reconsider her own shortcomings as a therapist and human being and examine how she contributed to the stressful circumstances, she distracts herself.

The humor comes out in the scene with the hypnotist who regresses Lilian. A hallucinatory sequence unfolds in the past taking her back to WW II and the Nazi occupation. This rational, reserved doctor accepts the hypnotist’s suggestions, after they discuss what she “saw” that relates to Paula. Suggesting Lilian had a romance with Paula in their past lives, she says this causes the crying. Apparently, she mourns Paula whom she loved during WWII as musicians in the same orchestra whose conductor was Simon.

Because Foster’s consummate acting skills elevate the scene to the edge of credulity, we follow Lilian’s acceptance of the hypnotist’s analysis, despite its ridiculousness.

As one fantastic notion leads to another, Lilian believes either Valerie or Simon murdered Paula. Since Lilian refuses to look at the prescription she wrote for Paula’s medication which Valerie hands to her as proof of negligence, we understand why she may choose to cling to the hypnotist’s analysis. Lilian would rather believe in a fantasy than examine her own actions as Valerie suggests she do. As a result she becomes obsessed with investigating foul play which involves Paula’s murder by the usual suspects, those closest to her.

Additional events occur which prompt Lilian to believe her suspicions are correct. In her adventures, she elicits Gabriel’s help after she shares her ideas with the police. Gabriel hops onboard the investigation out of love and attraction to his former wife. Together, their search for the truth becomes a caper they enjoy. As they uncover clues, this rational physician continues with the irrational in search of Paula’s murderer. Happily excited, she discovers a motive for their prime suspect. During these segments, which involve skullduggery on a rainy night, witnessing a sexual act, and searching where they shouldn’t, the director employs Foster and Auteuil’s prodigious acting talents. The humor, suspense, thrilling adventure, and resurgent romance they create between the characters engage and delight us.

The director gives a nod to classic films in the murder mystery genre from Hitchcock to Woody Allen. However, the final clue to the true circumstances are suggested by Lilian’s psychiatrist Dr. Goldstein (Frederick Wiseman). Perhaps the events she construes redirect her from the truth of the circumstances about the medication she prescribed for Paula. So what events happened and what didn’t? And what of the hallucinations and during regression and flashback visions afterward when Paula speaks to her? Which ring true?

With three or four twists, humorously sidelined by the director, eventually Lilian finds her way back to rationality. There, she meets herself coming. Also, she reconciles with family and understands how to be a better psychoanalyst in a humorous conclusion.

Foster steers the film with grace, likability and frenetic energy as the character attempts to discover a truth she has made for herself without realizing it. Eventually, she does. Thanks to great supporting performances by Auteuil and others, A Private Life delivers. The film resonates, more of a gem to revisit and appreciate than an eye-catching knockout to forget. https://www.filmlinc.org/nyff/films/a-private-life/

‘Father Mother Sister Brother’ With Adam Driver, Cate Blanchett, Tom Waits @NYFF

Father Mother Sister Brother

Jim Jarmusch’s Golden Lion award winner at the Venice Film Festival is a quiet, seemingly unadventurous film that nevertheless packs a punch. Instead of car chases and bombs exploding, Jarmusch employs subtext, nuance and quietude to convey family alienation.. His dangerous IUDs include slight gestures, a raised eyebrow here, a smile there and stilted, abrupt silences throughout.

Jarmusch quipped in the Q and A during the 63rd NYFF screening about such captured details of human behavior. To focus on nuances and what they reveal becomes much more difficult to film and edit rather than “12 zombies coming out of the ground.” Certainly the laconic characters portrayed by superb award winning actors (Charlotte Rampling, Adam Driver, Cate Blanchette, Tom Waits, Vicky Krieps, the beautiful Indya Moore and Luka Sabbat), hold one’s attention as masters of understatement. Indeed, Jarmusch forces us to carefully observe them because of what they don’t say, as they ride the pauses between what they do express.

Jarmusch’s triptych of meet-ups among family members rings with authenticity. Principally because Jarmusch wrote the parts for the actors he selected, the dialogue and situations unfold seamlessly. Of course the stilted silences fill in the gaps between parents and children when both are fronting about what is true and real. To what extent do we cut off 80% of what we would like to say to “keep the peace,” “mask our true emotions” or “get over?”

The film divides familial separation into three scenarios in three locales. In the last sequence, the separation has no hope of reconciliation. In the first scenario a slick, quirky father (Tom Waits) hosts his children (Adam Driver, Mayim Bialik). In their ride to his house in a wooded area by a lake, the brother and sister discuss how their father has difficulty making ends meet and may have dementia. Ironically, when they share that he hits them up for money, they haltingly discuss that they give it to him. Sister Mayim Bialik humorously comments that the frequency and amount may have contributed to her brother’s divorce. Then she ruefully realizes her insulting remark and apologizes. Their conversation reveals, they too, display an awkwardness with each other.

Of course this ramps up when they sit down with their father who offers them only water to drink, instead of something more. However, his wife, their mother passed, so assumptions abound. For example, they assume his shabby, messy living room signifies he struggles with her loss. And perhaps his lack of funds and sloppiness reveal a purposelessness in his own life without her. However, when Jarmusch has the children leave, we note the reality behind the assumptions. Waits’ Dad transforms into someone else. Not only have the grown children underestimated their father, they’ve completely misread his personality, character and intentions.

The scene is heavy with humor. Indeed, it reminds us that the Italian proverb “You have to eat 100 pounds of salt with someone to understand them,” isn’t an exaggeration. And this thematic thrust Jarmusch has fun with in the next scenario as well.

The second interlude takes place in Ireland, where a wealthy novelist mother (Charlotte Rampling) hosts a formal tea for her grown daughters who live in Dublin (Vicky Krieps and Cate Blanchett). The lush setting and table filled with all the proper treats for an afternoon tea impress. However, the sophistication of the setting adds to the cold atmosphere among the daughters and mother who play act at niceties. The daughters appear at opposite ends of their lives. Kreps with pink hair contrasts with Blanchett outfitted with glasses, short cropped hair and regressed to dour blandness. Rampling’s remote, regal mom presides over all austerely.

Before the daughters arrive, the mother reveals her attitude about the tea. Krieps alludes to a relationship with another woman. However, none of the interesting frequencies in their real lives come to the table. Instead, they drink tea politely accomplishing a duty to their blood. Truly, folks may be related by DNA, but their likenesses, interests, values and personalities may have little alignment with their blood kinship. We do choose our friends and are stuck with family relations.

Interestingly, the third segment returns to the theme of children not understanding their parents, who grow up in a different time warp. In Paris, two lovely-looking fraternal twins (Indya Moore and Luka Sabbat) make a return visit to their late parents’ spacious apartment. Their parents, who died in a plane crash, have separated from them for the rest of their mortal lives. As they walk through the empty apartment then go to their parent’s storage unit, they confront the impact of their parent’s deaths. Additionally, they marvel at their parents’ things. These had little significance to them but had meaning to their parents who kept them and paid for the storage.

Of the three scenarios, in the last one Jarmusch reveals the love between the siblings. Additionally, he reveals a potential closeness to their parents. As they go through a few old photos, they show their admiration and they mourn. However, what remains but memories and the stuff in the storage unit whose meaning is lost to them? The heartfelt poignance of the last scenario contrasts with the other family scenarios and lightly holds a greater message that Jarmusch doesn’t shove down our throats.

Jarmusch’ Father Mother Sister Brother reveals profound concepts about family, human complication and mystery of every human being, who may not even be knowable to themselves.

Father Mother Sister Brother releases in US theaters at a perfect time for family gatherings, December 24, 2025 via MUBI, where it will stream at a later date. For the write up and information at the 63rd NYFF, go to this link. https://www.filmlinc.org/nyff/films/father-mother-sister-brother/

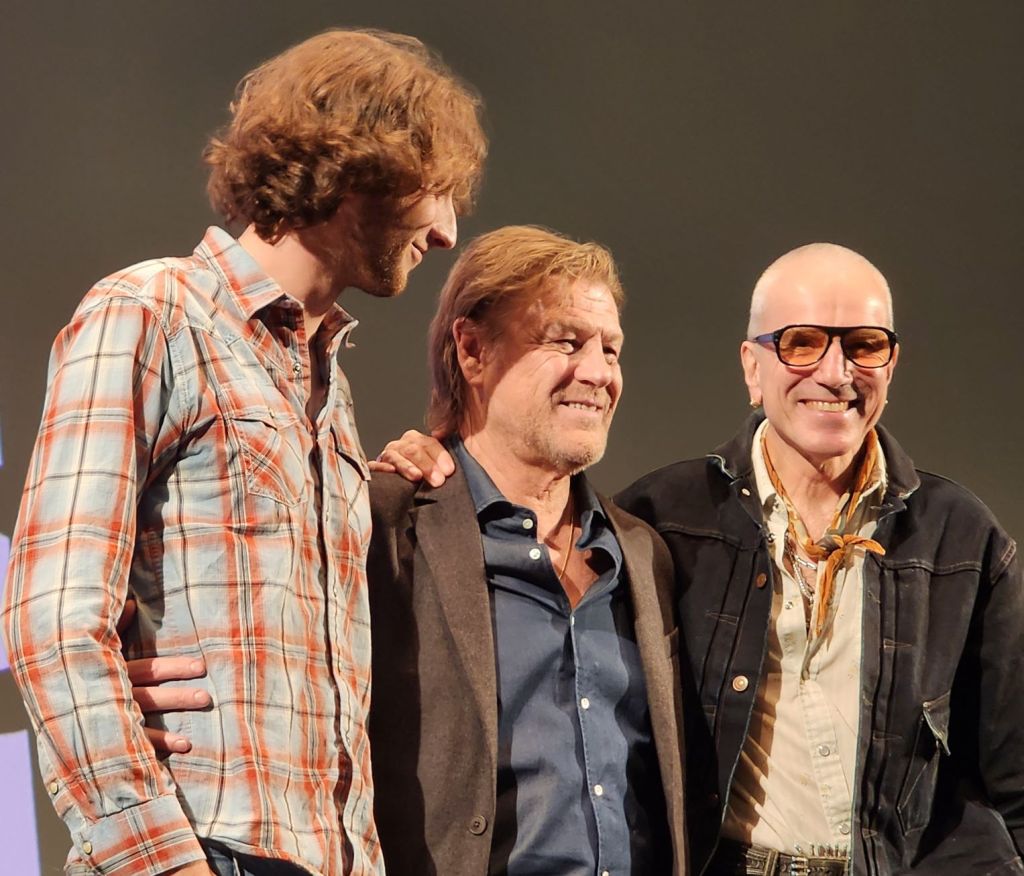

‘Anemone’ @NYFF Brings Daniel Day-Lewis’ Sensational Return

Supporting his son Ronan Day-Lewis’ direction in a collaborative writing effort, Daniel Day-Lewis comes out of his 8-year retirement to present a bravura performance in Anemone. The film, his son’s directing debut, screened as a World Premier in the Spotlight section of the 63rd NYFF.

Ronan Day-Lewis’ feature resonates with power. First, the eye-popping natural landscapes captured by Ben Fordesman’s cinematography stun with their heightened visual imagery. Secondly, the striking, archetypal symbols illuminate redemptive themes. Day-Lewis uses them to suggest sacrifice, faith and love conquer the nihilistic evils visited upon Ray (Daniel Day-Lewis) and ultimately his entire family.

Finally, the emotionally powerful, acute performances, especially by Daniel Day-Lewis’ Ray and Sean Bean’s Jem, help to create riveting and memorable cinema.

The title of the film derives from the anemone flower’s symbolic, varied meanings. For example, one iteration relates to Greek mythology in the story of Aphrodite, whose mourning tears, shed after her lover Adonis’ death and loss, fell on the ground and blossomed into anemones. Also referenced as “windflowers,” anemone petals open in spring and are scattered on the wind. Possibly representing purity, innocence, honesty and new beginnings, the film’s white anemones grow abundantly in the woodland setting where reclusive Ray makes his home in a Northern England forest.

In a rustic, simplistic hermit-like retreat Ray lives in self-isolation, alienated from his family. Then one day, his brother Jem, prompted by his wife Nessa (Samantha Morton), mysteriously arrives. The director focuses on the action of his arrival withholding identities. Gradually through the dialogue and the rough interactions, heavy with paced, long silences, we discover answers to the mysteries of the estranged family. Furthermore, we learn the characters’ tragic underpinnings caused by searing events from the past. Finally we understand their motivations and close bonds despite the estrangement. By the conclusion family restoration and reconciliation begins.

Unspooling the backstory slowly, the director requires the audience’s patience. Selectively, he releases Ray’s emotional outbursts. These reveal his decades long internal conflict with himself, for not standing up to the perpetrators of his victimization. Neither Jem nor Nessa (Samantha Morton), Ray’s former girlfriend who Jem married after Ray abandoned her and their son, know his secrets. However, the slow revelations of abuse spill out of Ray, as Jem lives with him and endures his ill treatment and rage.

Each brief teasing out of pain-laced information that Jay spews impacts Jem. Because Jem receives strength and understanding from his faith, he puts up with Ray. Indeed, the various segments of Jay’s story seem structured as turning points. Each moves us deeper into Jay’s soul and Jem’s acceptance. Cleverly, by listening to his brother and encouraging him to speak, Jem breaks down Ray’s resistance.

Ray and Jem’s emotional releases trigger and manipulate each other. Once set off, the revelations full of anguish and subtext fall in slow motion like dominoes. Then, climactic sequences augment to an explosive series of events. One, a treacherous wind and hail storm, represents the subterranean rage and turmoil which all of the characters must expurgate before they can heal and come together.

Jay particularly suffered and needs healing. Throughout his life the patriarchal institutions he trusted betrayed and abused him. From his home life (his father), to the church (a cleric), and the military (his immediate superiors), emotional blows attack his soul and psyche. Also, the military makes an example of him. Not only was the abuse unjustified and misunderstood, the perpetrators covered it up and forced his silence. The cruel, forced complicity makes his life a misery in a perpetuating cycle of guilt and shame.

As a result, because Jay’s self-loathing pushes him deeper within his pain, he can’t discuss what happened with his family or anyone else. Of course, he refuses to get help in therapy. Instead, he escapes into nature for solace and peace. The society’s corruptions and his family’s still embracing the institutions that abused him stoke his anger and enmity.

Neglecting his brother Jem, Nessa and his son Brian, who is grown and needs him, Jay perpetrates a psychological violence on them. None of them understand Jay’s abandonment. Sadly, Ray’s absence and rejection shape Brian’s life. Embittered and violent, he endangers himself and others.

How Day-Lewis achieves Ray’s epiphany through Jem’s love occurs in an indirect line of storytelling, through Ray’s monologues and the edgy dialogue between Jem and Ray. By alternating scenes of Nessa and Brian in the city with the brothers in the forest, we realize that time is of the essence. Jem must convince Ray to return to their home to make amends with his son Brian as soon as possible because of a looming threat.

Ultimately, the slow movement in the beginning dialogue could have been speeded up with a trimming of the silences. However, Day-Lewis purposes the quiet between the brothers for a reason whether critics or audience members “get it” or not. The silences reveal an other-worldly, telepathic bond between the brothers. Likewise, on another level Ray’s son Brian connects with his father spiritually, though they are miles away. The director underscores this through Nessa who understands both father and son need each other. Nessa encourages Jem to bring Ray home to Brian. Day-Lewis also uses symbolic visual imagery to suggest the spiritual bond between father and son.

In Anemone, the themes run deep, as the filmmakers explore how love covers a multitude of hurts and wrongdoings. Anemone releases in wider expansion on October 10th in select theaters. For its 63rd New York Film Festival announcement go to https://www.filmlinc.org/nyff/films/anemone/