Category Archives: NYC Theater Reviews

Broadway,

Carrie Coon and Namir Smallwood are Frightening in Tracy Letts’ ‘Bug’

She’s a cocktail waitress. He’s a Gulf War vet. When they get together they create an unforgettable relationship in Tracy Letts’ sometimes comedic, mostly compelling psychological drama Bug, currently making its Broadway premiere at Manhattan Theater Club’s Samuel J. Friedman Theatre through February 8, 2026. Aptly directed by David Cromer for a maximum thrill ride, Agnes (Carrie Coon) and Peter (Namir Smallwood) gain each other’s trust in a world that increasingly threatens to destroy them.

Stellar performances by Coon (The White Lotus, The Gilded Age) and Smallwood (Pass Over on Broadway) carry the production through a slow build first act into the harrowing intensity and climactic finish of the second.

Letts’ chilling drama unfolds in a motel room on the outskirts of present-day Oklahoma City. Scenic designer Takeshi Kata features a typical mundane bedroom with cream colored walls and complementary cheesy lamps and appointments that spell out Agnes’ challenged socioeconomic position. By the second act, after a time interval during which Agnes and Peter panic and go through stages of emotional terror, the room’s once benign look transforms to a place whose inhabitants are under siege.

At this point Kata’s design shocks. It is then we understand how badly the situation has progressed in the minds of the characters .

At the top of the play we meet Agnes who lives in the motel room hiding out from her violent former husband Jerry Goss (Steve Key) an ex-convict. As Coon’s Agnes and her lesbian biker friend R.C. (Jennifer Engstrom) do drugs, R.C. warns Agnes to protect herself against Jerry whose prison release she questions because he is dangerous.

Ironically, Agnes asks about the background of the stranger using her bathroom. R.C. vouches for Smallwood’s Peter who she brought with her as they make their way to a party that R.C. also invites Agnes to. While R.C. is on the phone with personal business, Peter assures Agnes he is “not an axe murderer,” and expresses an interest in her.

Instead of going to the party with R.C., both Agnes and Peter decide to hang out together and talk, feeling more comfortable getting to know each other than being in a larger crowd. It is during these exchanges and Peter’s staying overnight at Agnes’ invitation that her emotional neediness clarifies. When Jerry shows up, they argue and he hits Agnes. After Jerry leaves, Peter’s attentiveness draws her closer to him. As Agnes and Peter settle in and do drugs, they share secrets and bond. Increasingly Agnes’ perspective shifts. She accepts Peter’s world view and personal reality despite its extremism.

Though Peter says he should go, Agnes uses his hesitation to encourage him to stay, insisting upon it. She makes a symbolic gesture that clever viewers will note conveys her acceptance of Peter because of her emotional desperation more than a belief in his perspective and backstory.

In the next act we see the extent to which Peter has made himself comfortable living with Agnes whose resolve against being with Jerry has strengthened because of her relationship with Peter. Because their concern and care for each other resonates with trust, Peter relaxes into himself. He examines his blood under a microscope and finds “proof” of a conspiracy theory that the government uses military vets and unsuspecting individuals as guinea pigs to experiment on. With convoluted half-truths about government cover-ups related to the war in Iraq, Oklahoma City bombing, the Tuskegee syphilis experiment and more, he panics, fearful that aphids bite him and Agnes, feed off their blood and infest their living space.

Convinced that egg sacks have been planted in him by doctors who also monitor and follow him with helicopters because he has gone AWOL, he persuades Agnes to accept his “bug” theory that he grounds in explanations. Together, they plan a way out of the infestation which has taken over their bodies and minds.

To complicate matters Dr. Sweet (Randall Arney) shows up and explains Peter’s medical case with R.C. and Jerry to legitimize taking Peter back with him to “Lake Groom.” Letts offers the intriguing possibility that there may be many truths about this situation. But without independent investigation and research, belief takes over. Whether Peter is part of an experiment and a guinea pig or not, Agnes expresses her love for him comforted by their bond which gives her life meaning. Within the horror of the infestation, they have found their emotional sustenance. Their relationship is their sanctuary from life’s pain.

Cromer’s vision and his shepherding of the fine performances by Coon and Smallwood make this stylized production all too real and terrifying. Thematically current, with various cultural attitudes related to government cover-ups, and conspiracy theories stoked by the questionable motives of those in power, the creative team’s efforts (Heather Gilbert’s lighting design, Josh Schmidt’s sound design) hit the sweet spot of relevance.

Though written decades ago, in Bug Letts intimates how and why certain women embrace what others deem to be their partner’s extremist perspectives. Wounded and seeking love, women like Agnes more easily accept their partner’s ideas, rather than search for facts and proof to dispute them. Governmental cover-ups of the truth fan the flames of extremist belief systems. The consequences can be socially and culturally devastating.

Bug runs 1 hour and 55 minutes with one intermission at the Samuel Friedman Theatre ( 47th St. between 7th and 8th) https://www.manhattantheatreclub.com/shows/2025-26-season/bug/

Kara Young and Nicholas Braun Fine-Tune Their Performances in ‘Gruesome Playground Injuries’

What do people do when they have emotional pain? Sometimes it shows physically in stomach aches. Sometimes to release internal stress people risk physical injury doing wild stunts, like jumping off a school roof on a bike. In Rajiv Joseph’s humorous and profound Gruesome Playground Injuries, currently in revival at the Lucille Lortel Theater until December 28th, we meet Kayleen and Doug. Two-time Tony Award winner Kara Young and Succession star Nicolas Braun portray childhood friends who connect, lose track of each other and reconnect over a thirty year period.

Joseph charts their growth and development from childhood to thirty-somethings against a backdrop of hospital rooms, ERs, medical facilities and the school nurse’s office, where they initially meet when they go to seek relief from their suffering. After the first session when they are 8-year-olds, to the last time we see them at 38-year-olds at an ice rink, we calculate their love and concern for each other, while they share memories of the most surprising and weird times together. One example is when they stare at their melded vomit swishing around in a wastepaper basket when they were 13-year-olds.

How do they maintain their relationship if they don’t see each other for years after high school? Their friends keep them updated so they can meet up and provide support. From their childhood days they’ve intimately bonded by playing “show and tell,” swapping stories about their external wounds, which Joseph implies are the physical manifestations of their soul pain. After Doug graduates from college, when Doug is injured, someone tips off Kayleen who comes to his side to “heal him,” something he believes she does and something she hopes she does, though she doesn’t feel worthy of its sanctity.

Joseph’s two-hander about these unlikely best friends alludes to their deep psychological and emotional isolation that contributes to their self-destructive impulses. Kayleen’s severe stomach pains and vomiting stems from her upbringing. For example in Kayleen’s relationship with her parents we learn her mother abandoned the family and ran off to be with other lovers while her father raised the kids and didn’t celebrate their birthdays. Yet, when her mother dies, the father tells Kayleen she was “a better woman than Kayleen would ever be.” There is no love lost between them.

Doug, whose mom says he is accident prone, uses his various injuries to draw in Kayleen because he feels close to her. She gives him attention and likes touching the wounds on his face, eyes, etc. Further examination reveals that Doug comes from a loving family, the opposite of Kayleen’s. Yet, he may be psychologically troubled because he risks his life needlessly. For example, after college, he stands on the roof of a building during a storm and is struck by lightening, which puts him in a coma. His behavior appears foolish or suicidal. Throughout their relationship Kayleen calls him stupid. The truth lies elsewhere.

Of course, when Kayleen hears he is in a coma (they are 28-year-olds), after the lightening episode, she comes to his rescue and lays hands on him and tells him not to die. He recovers but he never awakens when she prays over him. She doesn’t find out he’s alive until five years later when he visits her in a medical facility. There, she recuperates after she tried to cut out her stomach pain with a knife. She was high on drugs. At that point they are 33-year-olds. Doug tells her to keep in touch, and not let him drift away, which happened before.

Joseph charts their relationship through their emotional dynamic with each other which is difficult to access because of the haphazard structure of the play, listing ages and injuries before various scenes. In this Joseph mirrors the haphazard events of our lives which are difficult to figure out. Throughout the 8 brief, disordered, flashback scenes identified by projections on the backstage wall listing their ages (8, 23,13, 28, 18, 33, 23, 38) and references to Doug’s and Kayleen’s injuries, Joseph explores his characters’ chronological growth while indicating their emotional growth remains nearly the same, as when we first meet them at 8-years-old. In the script, despite their adult ages, Joseph refers to them as “kids.”

Toward the end of the play via flashback (when they are 18-year-olds), we discover their concern and love for for each other and inability to carry through with a complete and lasting union as boyfriend and girlfriend. When Doug tries to push it, Kayleen isn’t emotionally available. Likewise when Kayleen is ready to move into something more (they are 38-year-olds), Doug refuses her touch. By then he has completely wrecked himself physically and can only work his job at the ice rink sitting on the Zamboni.

Young and Braun are terrific. Their nuanced performances create their characters’ relationship dynamic with spot-on authenticity. Acutely directed by Neil Pepe, we gradually put the pieces together as the mystery unfolds about these two. We understand Kayleen insults Doug as a defense mechanism, yet is attracted to his self-destructive nature with which she identifies. We “get” his protection of her because of her abusive father. One guy in school who Doug fights when the kid calls her a “skank,” beats him up. Doug knows he can’t win the fight, but he defends Kayleen’s name and reputation.

The lack of chronology makes the emotional resonance and causation of the characters’ behavior more difficult to glean. One must ride the portrayals of Young and Braun with rapt attention or you will miss many of Joseph’s themes about pain, suffering and the salve for it in companionship, honesty and love.

In additional clues to their character’s isolation, Young and Braun move the minimal props, the hospital beds, the bedding. They rearrange them for each scene. On either side of the stage in a dimly lit space (lighting by Japhy Weideman), Young and Braun quickly fix their hair and don different costumes (Sarah Laux’s costume design), and apply blood and injury-related makeup (Brian Strumwasser’s makeup design). In these transitions, which also reveal passages of time in ten and fifteen year intervals, we understand that they are alone, within themselves, without help from anyone. This further provides clues to the depths of Joseph’s portrait of Kayleen and Doug, which the actors convey with poignance, humor and heartbreak.

Gruesome Playground Injuries runs 1 hour 30 minutes with no intermission through 28 December at the Lucille Lortel Theater; gruesomeplaygroundinjuries.com.

‘The Baker’s Wife,’ Lovely, Poignant, Profound

It is easy to understand why the musical by Stephen Schwartz (music, lyrics) and Joseph Stein (book) after numerous reworkings and many performances since its premiere in 1976 has continued to gain a cult following. Despite never making it to Broadway, The Baker’s Wife has its growing fan club. This profound, beautiful and heartfelt production at Classic Stage Company directed by Gordon Greenberg will surely add to the fan club numbers after it closes its limited run on 21 December.

Based on the film, “La Femme du Boulanger” by Marcel Pagnol (1938), which adapted Jean Giono’s novella“Jean le Bleu,” The Baker’s Wife is set in a tiny Provençal village during the mid-1930s. The story follows the newly hired baker, Aimable (Scott Bakula), and his much younger wife, Geneviève (Oscar winner, Ariana De Bose). The townspeople who have been without a baker and fresh bread, croissants or pastries for months, hail the new couple with love when they finally arrive in rural Concorde. Ironically, bread and what it symbolically refers to is the only item upon which they readily agree.

If you have not been to France, you may not “get” the community’s orgasmic and funny ravings about Aimable’s fresh, luscious bread in the song “Bread.” A noteworthy fact is that French breads are free from preservatives, dyes, chemicals which the French ban, so you can taste the incredible difference. The importance of this superlative baker and his bread become the conceit upon which the musical tuns.

Schwartz’s gorgeously lyrical music and the parable-like simplicity of Stein’s book reaffirm the values of forgiveness, humility, community and graciousness as they relate to the story of Geneviève. She abandons her loving husband Aimable and runs away to have adventures with handsome, wild, young Dominique (Kevin William Paul), the Marquis’ chauffeur. When the devastated Aimable starts drinking and stops making bread, the townspeople agree they cannot allow Aimable to fall down on his job. The Marquis (Nathan Lee Graham), is more upset about losing Aimable’s bread than the car Domnique stole.

Casting off long held feuds and disagreements, they unite together and send out a search party to return Geneviève without judgment to Aimable, who has resolved to be alone. Meanwhile, Geneviève decides to leave Dominique who is hot-blooded but cold-hearted. In a serendipitous moment three of the villagers come upon Geneviève waiting to catch a bus to Marseilles. They gently encourage her to return to Concorde, affirming the town will not judge her.

She realizes she has nowhere to go and acknowledges her wrong-headed ways, acting like Pompom her cat who also ran off. Geneviève returns to Aimable for security, comfort and stability, and Pompom returns because she is hungry. Aimable feeds both, but scolds the cat for running after a stray tom cat in the moonlight. When he asks Pompom if she will run away again, DeBose quietly, meaningfully tells Bakula’s Aimable, she will not leave again. The understanding and connection returns metaphorically between them.

Director Gordon Greenberg’s dynamically staged and beautifully designed revival succeeds because of the exceptional Scott Bakula and perfect Ariana DeBose, who also dances balletically (choreography by Stephanie Klemons). DeBose’s singing is beyond gorgeous and Bakula’s Aimable resonates with pride and poignancy The superb ensemble evokes the community of the village which swirls its life around the central couple.

Greenberg’s acute, well-paced direction reveals an obvious appreciation and familiarity with The Baker’s Wife. Having directed two previous runs, one in New Jersey (2005), the other at The Menier Chocolate Factory in London (2024), Greenberg fashions this winning, immersive production with the cafe square spilling out into the CSC’s central space with the audience on three sides. The production offers the unique experience of cafe seating for audience members.

Jason Sherwood’s scenic design creates the atmosphere of the small village of Concorde with ivy draping the faux walls, suggesting the village’s quaint buildings. The baker’s boulanger on the ground floor at the back of the theater is in a two-story building with the second floor bedroom hidden by curtains with the ivy covered “Romeo and Juliet” balcony in front. The balcony features prominently as a device of romance, escape or union. From there DeBoise’s Geneviève stands dramatically while Kevin William Paul’s Dominique serenades her, pretending it is the baker’s talents he praises. From there DeBoise exquisitely sings “Meadowlark.”

Greenberg’s vision for the musical, the sterling leads and the excellent ensemble overcome the show’s flaws. The actors breathe life into the dated script and misogynistic jokes by integrating these as cultural aspects of the small French community of Concorde in the time before WW II. The community composed of idiosyncratic members show they can be disagreeable and divisive with each other. However, they come together when they attempt to find Geneviève and return her to Aimable to restore balance to their collective, with bread for their emotional and physical sustenance.

All of the wonderful work by ensemble members keep the musical pinging. Robert Cuccioli plays ironic husband Claude with Judy Kuhn as his wife Denise. They are the cafe owning, long married couple, who serve as the foils for the newly married Aimable and Geneviève. They provide humor with wise cracks about each other as the other townspeople chime in with their jokes and songs about annoying neighbors.

Like the other townspeople, who watch the events with the baker and his wife and learn about themselves, Claude and Denise realize the lust of their youth has morphed into love and great appreciation for each other in their middle age. Kuhn’s Denise opens and closes the production singing about the life and people of the village who gain a new perspective in the memorable signature song, “Chanson.”

The event with the baker and his wife stirs the townspeople to re-evaluate their former outlooks and biased attitudes. The women especially receive a boon from Geneviève’s actions. They toast to her while the men have gone on their search, leaving the women “without their instruction.” And for the first time Hortense (Sally Murphy), stands up to her dictatorial husband Barnaby (Manu Narayan) and leaves to visit a relative. She may never return. Clearly, the townspeople inch their way forward in getting along with each other, to “break bread” congenially as a result of an experience with “the baker and his wife,” that they will never forget.

The Baker’s Wife runs 2 hours 30 minutes with one intermission at Classic Stage Company through Dec. 21st; classicstage.org.

Laurie Metcalf is Amazing in ‘Little Bear Ridge Road’

On 12 acres of property in Idaho on the top of the ridge, the sky is so intense it makes Ethan (Micah Stock) panicky because he feels that his life is insignificant against the vastness of the galaxy glittering before him. Sarah (Laurie Metcalf), Ethan’s aunt who owns the property and appreciates the nighttime view tells him she “thought once about buying a telescope, but you know. Then I’d own a telescope.” The audience laughter responding to Metcalf’s pointed, identifying statement that reveals her edgy, funny character peppers Samuel D. Hunter’s powerful, sardonic Little Bear Ridge Road currently at the Booth Theatre.

Metcalf is terrific as Sarah who delivers comments like darts hitting the bullseye and evoking laughter because her words are heavy with authenticity. Her statements convey meaning and pointedly eschew the gentility of polite conversation. Micah, Sarah’s nephew, is withdrawn, remote and masked, not only because the play begins during the COVID-19 pandemic, but because he wears his soul damage on the exterior with a covering of silence that withholds speech. Interestingly, these two estranged family members, one a nurse who doesn’t even nurture her own wounds, and the other, a self-damaged young man of thirty, who can’t really get out of his own way, eventually get along,

With this Broadway debut Hunter (The Whale, A Bright New Boise) weaves a poignant, humorous, fascinating dynamic. Metcalf and Stock inhabit these individuals with humanity and a fullness of life that is breathtaking.

Directed crisply with excellent pace and verve by Joe Mantello, Hunter’s comedic drama that premiered at Steppenwolf Theater Company, confronts human isolation and failed familial relationships. Hunter presents individuals who confuse self-supporting independence with misguided self-reliance. With spare, concise dialogue the playwright explores how Metcalf’s Sarah and Stock’s Ethan rekindle their sensitivity and open up while nursing their fractured, self-victimized souls, to help each other without acknowledging it as help.

Finally, Hunter’s dialogue has flourishes of well-placed poetic grace and rhythm. Within its meta-themes about human beings struggles with themselves, it’s also about knowing when to let go to encourage another’s growth.

Aunt Sarah and nephew Ethan have an ersatz reunion, when Ethan’s father, Sarah’s brother, dies and leaves the nearby house and estate to Ethan to dispose of. Estranged from his father and from her for a number of years, Ethan, who is gay, lived in Seattle with a partner, who emotionally abused him and self-medicated with a cocaine habit. Eventually, they split. Graduating from university with an M.F.A. in writing, Ethan has drifted, stunned by his devastating childhood where he was raised by an addict father, since Ethan’s mother abandoned the family when he was little. How does Ethan learn not to duplicate his problematic relationship with his father, with love relationships with other older men?

For her part Sarah remained in Idaho near where she was born and worked as a nurse during and after her husband left her. Fortunately or unfortunately, they had no children. This means that she and Ethan are the only Fernsbys left on the planet, dooming their family line to extinction, which according to Ethan seems pathetic. Selling her home in Moscow, Sarah tells Ethan she moved to a more remote area because “It suits me better. Not being around—people.”

With her prickly, self-reliance and proud stance refusing help, Sarah has taken care of her house and property, worked, organized documents and paperwork for Leon (Ethan’s dad, her brother). She generously gave Leon money to help him with his bills. When Ethan affirms that was a bad idea because his addict father used it for his meth habit, Sarah states she doesn’t know what he used it for. After all, Leon told her that he never did meth in front of Ethan. The truth lies elsewhere.

As the pandemic passes and circumstances improve, the relationship between aunt and nephew also improves. They communicate more intimately. They watch a TV series and comment about the characters. The dialogue is funny and Sarah and Ethan become family. Assumptions and mistaken views are dismissed and overturned. Realistic expectations fill in the gaps. A surprise occurs when Ethan meets and forms an attachment with James (the excellent John Drea).

Hunter uses James as a catalyst, who provokes a turning point to continue the forward momentum of the play. James comes from a more privileged, loving background and is studying at a nearby university to be a star-gazer for real, an astrophysicist. With eloquence James explains the magnificence of Orion’s Belt to Ethan, as it relates to our sun. Sarah welcomes him and encourages his relationship with Ethan, until once more circumstances gyrate in another direction, all perfectly unfolding with the emotion of the characters.

Mantello arranges the interlocking dynamic among Sarah, Ethan and then James, center stage on a “couch in a void.” From there the characters converse, sit, enter and leave stage right (to an invisible kitchen), stage left (to bedrooms). The recliner couch on a turntable platform in different positions establishes the passage of time between 2020 and 2022. Scott Pask’s set and the lighting by Heather Gilbert are symbolic and interpretive. Our focus becomes the characters and the actors’ exceptional portrayals as they struggle to find a home with each other and themselves, until the threads of grace in their alignment come to a necessary end.

After all, the Fernsbys have to have a legacy, if not in offspring, then in words. And the respite and connections they find together talking and watching TV on a “couch in void” becomes the place where Ethan’s legacy in writing is born, and the Fernbys legacy prevails.

Little Bear Ridge Road runs 1 hour 35 minutes with no intermission at the Booth Theater through February 15th littlebearridgeroad.com.

Bobby Cannavale, James Corden, Neil Patrick Harris Are LOL in ‘Art’

Superb acting and humorous, dynamic interplay bring the first revival of Yasmina Reza’s Tony-award winning play Art into renewed focus. The play, translated from the French by Christopher Hampton, is about male friendship, male dominance and affirming self-worth. Directed by Scott Ellis, the comedy with profound philosophical questions about how we ascribe value and importance to items considered “art” as a way of bestowing meaning on our own lives resonates more than ever. Art runs until December 21st at the Music Box Theatre with no intermission.

When Marc (Bobby Cannavale) visits his friend Serge (Neil Patrick Harris) and discovers Serge recently spent $300,000 dollars on a white, modernist painting without discussing it with him, Marc can’t believe it. Though the painting by a known artist in the art world can be resold for more money, Marc labels the work “shit,” not holding back to placate his friend’s ego. The opening salvo has begun and the painting becomes the catalyst for three friends of twenty-five years to reevaluate their identity, meaning and bond with each other.

As a means to reveal each character’s inner thoughts, Reza has them address the audience. Initially Marc introduces the situation about Serge’s painting. After Marc insults Serge’s taste and probity, Serge quietly listens, makes the audience, his confidante and expresses to them what he can’t tell Marc. In fact Serge categorizes Marc’s opinion saying, “He’s one of those new-style intellectuals, who are not only enemies of modernism, but seem to take some sort of incomprehensible pride in running it down.” As Serge attempts to pin down Marc reinforcing Marc’s lack of expertise or knowledge about modern art, he questions what standards Marc uses to ascribe his valuable painting as “this shit.”

At that juncture Reza emphasizes her theme about the arbitrary conditions around assigning value to objects, people, anything. Without consensus related to standards, only experts can judge the worth of art and artifacts. Obviously, Marc doesn’t accept modernist experts or this painter’s work. He asserts his opinion through the force of his personality and friendship with Serge. However, his insult throws their friendship into unknown territory and capsizes the equilibrium they once enjoyed. The power between them clearly shifts. The white canvass has gotten in the way.

During the first thrust and parry between Marc and Serge in their humorous battle of egos, the men resolve little. In fact we learn through their discussions with their mutual friend Yvan (James Corden), they think that each has lost their sense of humor. The purchase of the painting clearly means something monumental in their relationship. But what? And how does Yvan fit into this testing of their friendship?

Marc’s annoyance that Serge purch,ased the painting without his input, becomes obsessive and he seeks out Yvan for validation. First he warns the audience about Yvan’s tolerant, milquetoast nature, a sign to Marc that Yvan doesn’t care about much of anything if he won’t take a position on it. During his visit with Yvan, Marc vents about Serge’s pretensions to be a collector. Though he knows he can’t really manipulate Yvan about Serge because Yvan remains in the middle of every argument, he still tries to influence Yvan against the painting.

Marc believes if Yvan tolerates Serge’s purchase of “shit” for $300,000, then he doesn’t care about Serge. Tying himself in knots, Marc considers what kind of friend wouldn’t concern himself with his friend getting scammed $300,000 for a shit panting? If Yvan isn’t a good friend to Serge, at least Marc shows he cares by telling Serge the painting is “shit.” Without stating it, Marc implies that Serge has been duped to buy a white canvass with invisible color in it he doesn’t see based on BS, modernist clap trap.

In the next humorous scene between Yvan and Serge, knowing what to expect, Yvan sets up Serge, who excitedly shows him the painting. True to Marc’s description of him, Yvan stays on the fence about Serge’s purchase not to offend him. However, when Yvan reports back to Marc about the visit, he disputes Marc’s impression that Serge lost his sense of humor. In that we note that Yvan has no problem upsetting Marc when he says that he and Serge laughed about the painting. However, when Marc tries to get Yvan to criticize Serge’s purchase, Yvan tells him he didn’t “love the painting, but he didn’t hate it either.”

In presenting this absurd situation Reza explores the weaknesses in each of the men, and their ridiculous behavior which centers around whose perception is superior or valid. Additionally, she reveals the balance inherent in friendships which depend upon routine expectations and regularity. In this instance Serge has done the unexpected, which surprises and destabilizes Marc, who then becomes upset that Yvan doesn’t see the import behind Serge’s extreme behavior.

Teasing the audience by incremental degrees prompting LOL audience reactions, Reza brings each of the men to a boiling point and catharsis. Will their friendship survive their extreme reactions (even Yvan’s noncommittal reaction is extreme) and differences of opinion? Will Serge allow Marc to deface what he believes to be “shit” for the sake of their friendship? In what way are these middle-aged men asserting their “place” in the universe with each other, knowing that that place will soon evanesce when Death knocks on their doors?

The humorous dialogue shines with wit and irony. Even more exceptional are the actors who energetically stomp around in the skins of these flawed characters that do remind us of ourselves during times when passion overtakes rationality. Each of the actors holds their own and superbly counteracts the others, or the play would seem lopsided and not land. It mostly does with Ellis’ finely paced direction, ironic tone, and grey walled set design (David Rockwell), that uniformly portrays the similarity among each of the characters’ apartments (with the exception of a different painting in each one).

Reza’s characters become foils for each other when Marc, Serge and Yvan attempt to assert their dominance. Ironically, Yvan establishes his power in victimhood.

Arriving late for their dinner plans, Corden’s Yvan bursts upon the scene expressing his character in full, harried bloom. His frenzied monologue explodes like a pressure cooker and when he finishes, he stops the show. The evening I saw the production, the audience applauded and cheered for almost a minute after watching Corden, his Yvan in histrionics about his two fighting step-mothers, fiance, and father who hold him hostage about parental names on his and his fiance’s wedding invitations. Corden delivers Yvan’s lament at a fever pitch with lightening pacing. Just mind-blowing.

The versatile Neil Patrick Harris portrays Serge’s dermatologist as a reserved, erudite, true friend who “knows when to hold ’em and knows when to fold ’em.” Cannavale portrays Marc’s assertive personality and insidiously sardonic barrel laugh with authenticity. Underneath the macho mask slinks inferiority and neediness. Together this threesome reveals men at the worst of their game, their personal power waning, as they dodge verbal blows and make preemptive strikes that hide a multitude of issues the playwright implies. They are especially unwinning at successful relationships with women.

Reza’s play appears more current than one might imagine. As culture mavens and influencers revel in promoting and buying brands as a sign of cache, the pretensions of superiority owning, for example, a Birkin bag, bring questions about what an item’s true worth is and what that “worth” means in the eye of the beholder. Commercialism is about creating envy and lust and the illusion of value. To what extent do we all fall for being duped? Does Marc truly care that his friend may have fallen for more hype than value? Conclusively, Yvan has his own problems to contend with. How can he move beyond, “I don’t like it, I don’t hate it.”

As for its own value, Art is worthwhile theater to see the performances of these celebrated actors who have fine tuned their portrayals to a perfect pitch. Art runs 1 hour 35 minutes with no intermission through Dec. 21 at the Music Box Theater. artonbroadway.com.

‘The Queen of Versailles,’ Fabulous Kristin Chenoweth Makes Dreams Realities

If the road to excess leads to the palace of wisdom (quote by English poet William Blake), do people know when they’ve reached their limit? When is enough enough? According to the themes of the new musical The Queen of Versailles, currently at the St. James Theatre, knowing this depends upon the seeker.

In the clever, sardonic musical, based on Lauren Greenfield’s titular documentary film and the life stories of Jackie and David Siegel, the question of excess and how to measure it shines into the darkness of American culture, conspicuous consumption, surgically enhanced, plastic looks, and meretricious values. With an ironic, humorous, no holds barred book by Lindsey Ferrentino, and music and lyrics by Stephen Schhwartz, the Siegel’s riches to more riches story, including the 2008 mortgage debacle, takes center stage. By the conclusion, the audience leaves shaken and maybe stirred, either with a bad taste in their mouths or with the prick of guilt in their consciences.

At its finest, The Queen of Versailles inspires the audience to peer into their own values and behavior and evaluate their souls to correct. Ultimately, it asks, do the Siegels have a worthwhile life or have they allowed their childhood poverty to overwhelm their good sense and inner emotional well being? Despite its ripe fun Ferrentino’s book and Schwartz’s music encourage a hard look at crass, materialistic greed that blinds the rich from using their largess for the social good. Lastly, it questions do the representative Siegels count the cost to live the oversized billionaire’s lifestyle which causes harm? To what extent has their craven indulgence choked off their lifeblood to their own destruction?

Starring an endearing, heartfelt and bubbly Kristin Chenoweth as the materially insatiable Jackie Siegel, and F. Murray Abraham as billionaire workaholic David Siegel, the New York premiere which has an end date of March 29, 2026, rings with disturbing truths. It’s farcical, dark elements present many themes. Chief among them is the theme that the Siegel’s shiny ostentation hides a sad emptiness that can never be fulfilled.

Framing the Siegel’s story with the key meme of Versailles, the mansion in France that 17th century Louis XIV, built as a memorial to his majesty, the opening scene and song (Pablo David Laucerica is King Louis XIV) replete with period chandeliers, furniture, costumed butlers and maids reveals how and why the Sun King built his palace on swampland (“Because I Can”). Without giving thought to the inequities in French society that necessitated the economic gap between royalty and its impoverished, destitute subjects, Jackie and David want one.

In a quick switch to the present (2006) we see the Siegel’s Versailles in progress. With construction scaffolding in the background and a documentary film crew in the foreground, Chenoweth’s Jackie glows as she sings “we want to have the very best for the biggest home in America because we can.” The fluid set design with appropriate props and pieces by Dane Laffrey, who also does the video design, brings perfect coherence to the Siegel’s intentions. It connects the idea of royal wealth manifest in Louis XIV’s lavish excess to their rich/famous lifestyle which reeks of tawdriness. Thanks to Michael Arden’s staging and direction and Cristian Cowan’s costumes, and Cookie Jordan’s hair and wig design, the shifts from the present to the court of Louis XIV and back solidly establish the trenchant themes of this profoundly current musical.

Presuming themselves American royalty, the Siegels hope to replicate a modern-day Versailles, like their mentor king. Indeed, they will best him. Their Versailles has whatever the family wants. This includes a jewelry-grade gem stone floor, an in-house Benihana (with all those tossed shrimp because David doesn’t like to stand on line), a spa, a pool with a stained glass roof, and a family wing with numerous bedrooms and bathrooms so Jackie doesn’t lose track of her seven kids.

After this opening salvo that mesmerizes like any show about the “lifestyles of the rich and presumptuous,” we discover that Jackie didn’t always come from wealth. In fact her story mirrors the old Horatio Alger “rags-to-riches” fable that Alger shaped into the American Dream, which abides today and which also influenced F. Scott Fitzgerald’s take on it in The Great Gatsby. Jackie, albeit a female dreamer, buys into the concept that if she pulls herself up with determination, works hard and does good works, she can lift herself into the upper classes.

We see how this manifests in the next segment of Chenoweth’s 17-year-old version of Jackie with her parents Debbie (Isabel Keating) and John (Stephen DeRosa) in their humble Endwell, New York home. Debbie and John count on Jackie to continue to work as many jobs as possible to become rich and famous like the titular show they watch together. Singing the song “Caviar Dreams,” a ballad that expresses beautifully a female Alger hero, we “get” Jackie’s drive and pluck to work day and night to achieve an engineering degree at IBM, then kick the job to the curb because it won’t give her wealth fast enough.

As she “keeps on thrustin” she makes a bold turn into marriage with alleged banker Ron (Michael McCorry Rose), who disappoints when he drags her to the Everglades, and opposes her Mrs. Florida win. When he physically abuses her, despite her pregnancy, Jackie leaves. Singing “Each and Every Day” beginning when Victoria is a baby, the scene switches to the present at the construction site and the teenage Victoria (the excellent Nina White) enters. Chenoweth’s Jackie soulfully finishes the song to Victoria in an important transitional moment. We understand Jackie as a survivor who loves her firstborn, who she claims saved her life.

Not only does Jackie not look back, we learn she and baby Victoria lived in an apartment which “barely fit the baby’s crib and Jackie’s sleeping bag.” However, always “thrustin’ forward,” she recognizes opportunity when she goes to a party where she meets David Siegel, the CEO of Westgate Resorts. As it turns out, his impoverished childhood was similar to hers and left him with dreams of extreme wealth. F. Murray Abraham does justice to David throughout, first as a “cowboy” in the wild west of timeshares as son Gary (the fine Greg Hildreth) sings with the ensemble “The Ballad of the Timeshare King.” Occasionally, for emphasis, Abraham’s David chimes in with irony.

For example, David’s sales force make “one hundred percent of their sales on the first day.” Gary sings, “George W.’s president now, thanks to David Siegel.” When folks can’t afford the timeshare, Siegel helps them with financing from his bank, so the ensemble sings joyfully, “Yippee-I-owe-you-owe-we-owe.” We recognize the sardonic humor for David’s dishing out sub-prime mortgages to “anyone who breathes.” Of course this adds to the mortgage crises of 2008 which taxpayers foot the bill for. Eventually, the sub-prime loans bring his empire to the brink of bankruptcy as the crash swallows whole billionaires like David.

At that point, Jackie and David have been married with children and are two years into the Versailles construction having cycled through songs of their outsized wedding (“Trust Me”), a honeymoon trip to Versailles bringing back a scene of King Louis XIV and his courtiers. Smartly, Ferrentino and Schwartz reinforce their themes by joining past and present in the reprise “Because I Can and the “Golden Hour.”

However, conflict looms on the horizon. Though David and Jackie live their wildest dreams and birth child after child, daughter Victoria feels miserable, insular and ugly. “I know mom wishes I was prettier,” she sings in the poignant “Pretty Wins.” And in Act II in the superb “Book of Random” Victoria sings from her journal, the thoughts that she keeps hidden. Unlike her mother Victoria grounds herself in her current feelings of sadness brought on by reality, escapism fueled by drug addiction and scorn for their damaging and excessive lifestyle. However, when Jackie’s niece Jonquil (Tatum Grace Hopkins) arrives and Jackie takes her in, we think that Victoria has someone to confide in.

But Jonquil doesn’t understand Victoria’s dislike of Jackie’s appetite for more. And it doesn’t help Victoria that Jonquil becomes a clone of Jackie (“I Could Get Used to This.”). Ironically, when the crash happens and Victoria hears of the talk that they will sell Versailles to keep David from going belly up, she feels relief. In a farce-filled scene in the 17th century Versailles, with some of the most ironic lyrics, the Sun King chides the Siegels and Americans in the song “Crash.” “You thought you’d be egalitarian, let peasants own their own homes in some altruistic plan. Well, what were you expecting from a choice so rash? Crash…”

At the end of Act I, we have only Jackie’s spunk and perseverance (“This is Not the Way”), and David’s connections to rely on to bail them out of bankruptcy and foreclosure. Act II reveals that deus ex machina saves them when the government (taxpayers) bail out billionaires and banks. Naturally, the little people with no safety net lose their shirts. Where the peasants of France revolted against their royals (there is a humorous scene with the luckless Marie Antoinette on her way to the guillotine), in America, no one goes to jail because the banks and firms are “too big to fail.”

At the end of Act II, in a scene with King Louis XIV, in a reprise of “Crash,” King Louis and his courtiers sing as Marie Antoinette says “goodbye.” Here, Schwartz’s lyrics and tune underscore a crucial theme. America’s Aristocracy has cleverly worked it out that “democracy” will prevent revolutions. How? The rich have peasants “thinking they’re tomorrow’s millionaires; that you’re special privileges will someday soon be theirs.” And the ensemble adds, “No blade across the throat for you. Instead it seems your peasant class will all turn out to vote for you!” Thus, with no accountability for wrecking the economy and countless lives, the rich get richer, and Jackie and David, out of bankruptcy, continue building Versailles.

However, in all of the mayhem of trying to regain solvency, the Siegels sacrifice a family member. If material empires go on for centuries, flesh and blood does not. The unreality of excess belies mortality. But some folks never learn. Schwartz and Ferrentino ironically underscore this as Chenoweth’s Jackie holds a glass of champagne standing in front of a ring light. She speaks to a social media audience and hopes that, like her, they get their “champagne wishes and caviar dreams.”

The Queen of Versailles runs 2 hours 40 minutes with one intermission at the St. James Theatre. https://queenofversaillesmusical.com/

‘The Other Americans,’ John Leguizamo’s Brilliant Play Targeting the American Dream Extends Multiple Times

After a long career in every entertainment venue from films, to TV, to theater, Broadway, Off Broadway, etc., the prodigious work by the exceptional John Leguizamo speaks for itself. Now, Leguizamo tackles the longer theatrical form in writing The Other Americans, extended again until October 24th at the Public Theater.

Superbly directed by Ruben Santiago-Hudson, the theatrical elements of set design, lighting, costumes speak to the 1990s setting and cultural nuances. The following creatives developed a smart, stylish representation of the Castro household (Arnulfo Maldonado-set design, Kara Harmon-costumes, Justin Ellington-sound, Lorna Ventura-choreography).

Perhaps Leguizamo’s play could be tweaked to tighten the dialogue. All the more to have it shine with blinding, unforgettable truths sounding the alarm for immigrants in this nation. If tightened a bit, the complex, profound play would land perfectly as the unmistakable tragedy it inherently is. However, in its current iteration, Leguizamo gets the job done. The powerful play with comedic elements resonates to our inner core as a nation of immigrants and especially for Latinos.

Clearly, Leguizamo’s characterizations and themes add to the canon of classics that excoriate and expose the corrupted myth of the American Dream as a lie fitted to destroy anyone who believes it. That immigrants make the sacrifices they do to embrace it, is the ultimate tragedy.

Nelson Castro (played exquisitely by John Leguizamo), born in Jackson Heights from Columbian ancestry, embraces the American Dream. His wife Patti (the amazing Luna Laren Velez), from her Puerto Rican heritage, not so much. Patti’s values lead to loving her family and friends with devotion. Daughter, Toni (Rebecca Jimenez), who will marry the solid but nerdy Eddie (Bradley James Tejeda), looks to fit in as a white woman. The younger Nick (Trey Santiago-Hudson) was like his dad and took advantage of others, fiercely competitive. However, an incident changed him forever.

As the play unfolds, Leguizamo deals with the central question. To what extent have the warped values of the predominant culture negatively impacted this Latino family? From his first speech on we note that these twisted values have lured Nelson. The ethos-scam to get ahead-guides Nelson like a veritable North Star. He uses “getting over” as the key reason to provide for his family. This excuse rots everything under his power.

For example, Nelson acts the part of the upwardly mobile success story who always has a deal on the table ready to go. The irony is not lost on us when Nelson hypes a deal with a real estate big wig. Meanwhile, the mogul lives off his reputation for ripping off minorities. Sadly, Nelson admires the mogul’s pluck and con abilities. He ignores how this can potentially harms Latinos.

Mirroring the sick culture and society that values money and material prosperity over people, Leguizamo’s tragic hero tries to wheel and deal to get ahead. Making bad decisions, he overextends himself. Meanwhile, he encourages Nick and Toni to follow his lead. His overweening pride as the patriarch drives him to assume the mantle of a power player. Indeed, the opposite is true. During the process that causes him to fail and lie about it, he compromises his integrity and family’s probity and sanctity. That he willfully blinds himself to the consequences of his beliefs and suppresses his intelligence and good will to fit in, is the final heart breaker.

As in the classic tragic hero, Nelson’s pride also dupes him into a psychotic circularity to believe he has no recourse. Of course he believes the wheels have been set in motion against him by the society’s bigotry and discriminatory values. He should recognize and reject the society that uplifts such values because they support doing whatever necessitates getting ahead. The entire rapacious structure promotes financial terrorism and, whenever possible, it must be rejected. However, Nelson can’t reject it because he can’t help himself from being seduced. Instead, he persists in a prison of his own making, digging his family grave, on a collusion course of self-destruction.

Sadly, he internalizes the society’s inhumanity and makes it his own, a self-hating Latino. Because he adopts this construct because he loathes his immigrant self, he tries to create a new identity apart from his inferior ancestry. Thus, he moves to Forest Hills away from Jackson Heights where he lived “like an immigrant” in a place where cockroaches multiplied.

Finally, as we watch Nelson struggle to assert this new identity in a flawed, indecent, racially institutionalized culture (represented by Forest Hills and what a group of kids did to his son in high school), Leguizamo’s play asserts an important truth for immigrants. Internalizing and adopting the culture’s corrupt, sick, anti-human values is not worthy of immigrants’ sacrifices. This theme is at the heart of Leguizamo’s play. In his plot development and characterizations Leguizamo reveals his tragic hero chases after prosperity and upward mobility. The incalculable loss of what results-losing what it means to be human-isn’t worth it. If one does not weep for Leguizamo’s Nelson at the play’s conclusion, you weren’t paying attention.

To exemplify his themes, Leguizamo uses the scenario of the Castros, an American Latino family. They move from the homey, culturally diverse Jackson Heights to the white, Jewish upscale, racist enclave of Forest Hills. At the outset of the play Nelson, a laundromat owner, awaits his son’s return from a psychiatric facility. Patti has cooked up her son’s favorite dishes. Not only does this reveal her care and concern for her son, her comments to Nelson show her nostalgia for the Latin foods and people of their original Jackson Heights neighborhood in Queens.

By degrees Leguizamo reveals the mystery why Nick was in a facility. Additionally, the playwright brilliantly explores the conflicts at the heart of this family whose parents put their stake in their children, chiefly son Nick to get ahead financially in the Castro business. To recuperate, the doctors partially helped Nick with medication and therapies.

However, on his return home months later, he still suffers and has episodes. Patti sees the change in his dislike of his old favorite foods (symbolic). Not only does he reject meat, he rejects Catholicism and turns to Buddhism. Because a girl he met at the facility influences him, he moves away from his Latin roots. Later, we learn he loves and admires her and they plan to live together. However, he doesn’t look at the difficulties of this dream: no money, no family support.

The family conflicts explode when Nick attempts to be truthful with his parents. In his conversation with his mother we learn the horrific details of the beating he received in high school, why it happened, and how it led to episodes in college. Wanting to move beyond this through understanding, Nick learns in therapy that he must talk to his father. Nelson refuses to acknowledge what happened, and becomes a stalemate to Nick’s progress.

Additionally, his doctor supports Nick’s getting out from under the family’s living arrangements. Inspired, Nick yearns to create a life for himself away from their control to be his own person. Ironically, he follows in his father’s footsteps wanting to create a new identify for himself. Yet, he can’t create this identity unless he confronts the truth of what happened to him in high school and talks to his father. Unless he understands the extremely complex issues at the heart of his father’s tragedy, they won’t move forward together. Nelson must understand that he hates his own immigrant being and has embraced sick, twisted corrupt values which he never should have pushed on his family.

Meanwhile, in a fight with Nelson, Nick demonstrates what may really be happening to him. Though he survived the high school beating with a baseball bat, he most probably suffers from what doctors have come to understand as TBI (traumatic brain injury). With TBI the individual suffers debilities both physically and emotionally. When Nelson questions the efficacy of the treatment Nick received from doctors who didn’t really know what was happening to Nick, Nelson is on the right track. But the science had to catch up to Nelson’s observations.

Meanwhile, the problems relating to Nick needing the right help from his parents and his doctors, Nelson’s financial doom and the future of this Latino family under duress are answered in a devastating, powerful conclusion.

There is no spoiler. Leguizamo elegantly and shockingly reveals this family as a microcosm of the ills of our culture and society. Additionally, he sounds the warning for immigrants. If they don’t recognize and refuse the twisted folkways of the “American Dream,” they may lose their self-worth and humanity for a for a lie.

The Other Americans runs 2 hours 15 minutes including an intermission at The Publica Theater until November 23, 2025. https://publictheater.org/theotheramericans

Keanu Reeves, Alex Winter carry Ted and Bill into the adventure of ‘Waiting for Godot’

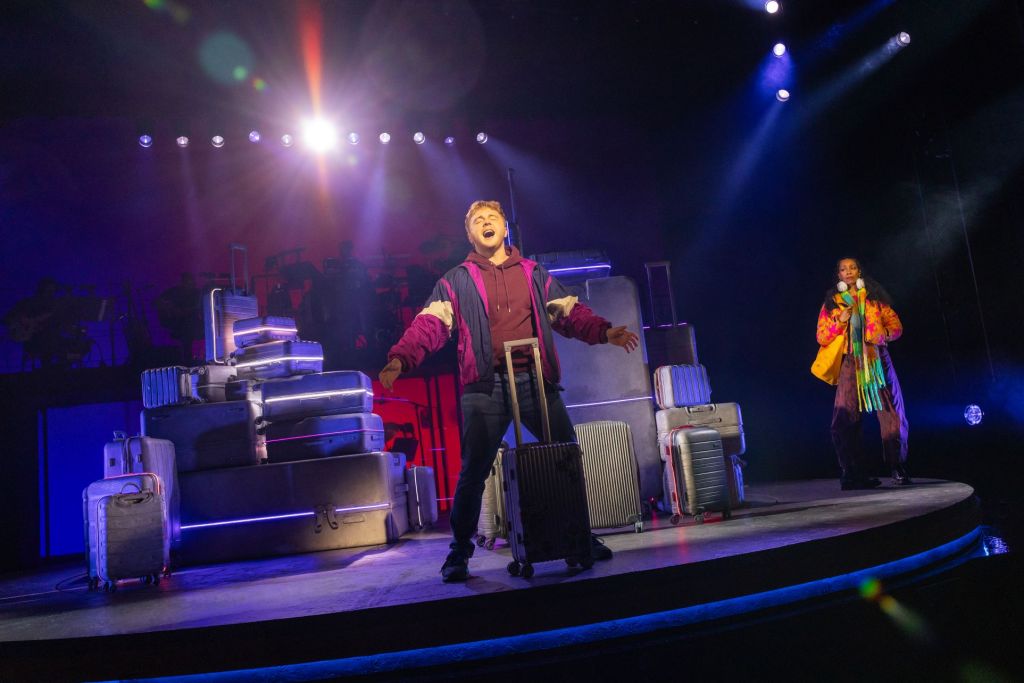

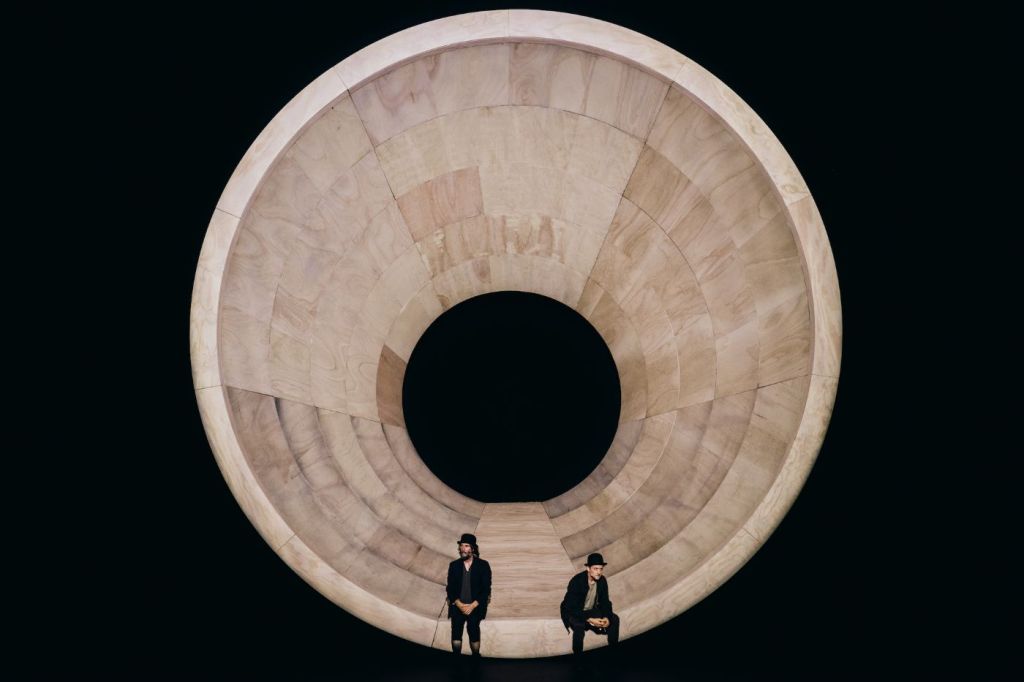

Referencing the past with Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure movie series, something has happened. Bill (Alex Winter) and Ted (Keanu Reeves), who long dropped their younger selves and reached maturity in Bill and Ted Face the Music (2020), have accomplished the extraordinary. They’ve fast forwarded to a place they’ve never been before in any of their adventures. An existential oblivion of uncertainty, Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

There, they cavort and wallow in a hollowed out, megaphone-shaped, wind-tunnel (Soutra Gilmore’s clever set design). The gaping maw is starkly, thematically lighted by Jon Clark. Ben & Max Ringham’s sound design resonates the emptiness of the hollow which Winter’s Valdimir and Reeves Estragon fill up to the brim with their presence. And, among other things, Estragon loudly snacks on invisible turnips and carrots, and some chicken bones.

Oh, and a few others careen into their empty hellscape. One is a pompous, bullish, land-owning oligarch with a sometime southern accent, whose name, Pozzo, means oil well in Italian (a superb Brandon J. Dirden in a sardonic casting choice). And then there is his slave, for all oligarchs must have slaves to lord over, mustn’t they? Pozzo’s DEI slave in a wheelchair, seems misnamed Lucky (the fine Michael Patrick Thornton).

However, before these former likenesses of their former selves show up and startle the down-on-their luck Vladimir and Estragon, the two stars of oblivion wait for something, anything to happen. Maybe the dude Godot, who they have an arrangement with, will show up on stage at the Hudson Theatre. Maybe not. At the end of Act I he sends an angelic looking Boy to tell them he will be there tomorrow. A silent echo perhaps rings in the stillness of the oblivion where the hapless tramps abide.

Despite the strangeness of it all, one thing is certain. Bill and Ted are together again for another adventure that promises to be like no other. First, they’ve landed on Broadway, dressed as hobos in bowler hats playing clowns for us, who happily watch and wait for Godot with them. And it doesn’t matter whether they tear it up or tear it down. The excellent novelty of these two appearing live as Didi (Vladimir) and Gogo (Estragon), another dimension of Bill and Ted, illuminates Beckett.

Keanu Reeves’ idea to have another version of their beloved characters confront Samuel Beckett’s tragicomical questions in Waiting for Godot seems an anointed choice. It is the next step for these bros to “party on,” albeit with unsure results. However, they do well fumfering around in this hollowed out world, a setting with no material objects. The director has removed the tree, the whip, or any props. Thus, we concentrate on their words. Between their riffs of despair, melancholy, hopelessness and trauma, they have playful fun, considering the existential value of life. Like all of us, if they knew what circumstances meant in the overall arc of their lives, they wouldn’t be so lost.

Director Jamie Lloyd, unlike previous outings (A Doll’s House, Sunset Boulevard), keeps Beckett’s script without alteration. Why not? Rhythmic, poetic, terse, seemingly repetitive and excessively opaque, in their own right, the spoken words ring out, regardless of who speaks them. That the characters of Bill and Ted are subsumed by Beckett’s Didi and Gogo makes complete sense.

What would they or anyone do if there was no intervention or salvation as occurs fancifully in the Bill and Ted adventure series? They’d be waiting for salvation, foiled and hopeless about the emptiness and uselessness of existence without definition. Indeed, politically isn’t that what some in a nation of unwitting, passively oppressed do? Hope for salvation by a greater “someone,” when the only possibility is self-defined, self-salvation? How long does it take to realize no one is coming to help? Maybe if they help themselves, Godot will join in the work of helping them find their own way out of oblivion. But just like the politically passive who do nothing, the same situation occurs here. Godot is delayed. Didi and Gogo do nothing but play a waiting game.

From another perspective eventually unlike political passives they compel themselves to act. And these acts they accomplish with excellent abandon. They have fun.

And so do we watching, listening, wondering and waiting with them. Their feelings within a humorous dynamic unfold in no particular direction with a wide breadth of expression. Sometimes they want to hang themselves to end the frustration. Sometimes, bored, they engage in swordplay with words. Sometimes they rage. Through it all they have each other. And despite wanting to separate and go their own ways, they do find each other comforting. After all, that’s what friends are for in Jamie Lloyd’s anything is probable Waiting for Godot.

In Act I they are tentative, searching their memories for where they are and if they are. Continually, they circle the truth, considering where the one is who said they were coming. However, the situation differs in Act II because the Boy gave them the message about Godot.

In Act II they cut loose: chest bump, run up and down their circular environs like gyrating skateboarders seamlessly navigating curvilinear walls. By then, the oblivion becomes familiar ground. They relax because they can relax, accustomed to the territory. And we spirits out there in the dark, who watch them, become their familiar counterparts, too. Maybe it’s good that Godot isn’t coming, yet. They may as well while away the time. Air guitar anyone? Yes, please. Reality is what we make it. Above all, we shouldn’t take ourselves too seriously. In the second act they don’t. After all, they could turn out like Pozzo and Lucky. So they do have fun while the sun shines, until they don’t and return right back to square one: they wait.

As for Pozzo and Lucky a further decline happens. In Act I Lucky gave a long, unintelligible speech that sounded full of meaning. In Act II Lucky is mute. Pozzo, becomes blind and halt, dependent upon Lucky to move. He reveals his spiritual and physical misery and haplessness by crying out for help. On the one hand, the oppressor caves in on himself via the oppression of his own flesh. On the other hand, he still exploits Lucky whom he leads, however awkwardly. The last shreds of his bellicosity and enslavement of Lucky hang by a thread.

Pozzo has become only a bit less debilitated than Lucky, whereas before, his identity commanded. Fortunately for Pozzo Lucky doesn’t revolt and leave him or stop obeying him. Instead, he takes the role of the passive one, while Pozzo still acts the aggressor, as enfeebled as he is. The condition happened in the twinkling of an eye with no explanation. Ironically, his circumstances have blown most of the bully out of him and reduced him to a pitiable wretch.

Nevertheless, Didi and Gogo acknowledge Pozzo and Lucky’s changes with little more than offhanded comments. What them worry? Their life-giving miracle happened. They have each other. It’s a congenial, permanent arrangement. After that, when the Boy shows up to tell them the “bad” news, that Godot has been delayed, yet again, and maybe will be there tomorrow, it’s OK. There’s no “sound and fury” as there is in Macbeth’s speech about “tomorrows.” We and they know that they will persist and deliver themselves and each other into their next clown show, tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.

If one rejects the comparison of this version of Waiting for Godot with others they may have seen, that wisdom will yield results. To my thinking comparing versions takes the delight out of the work. The genius of Beckett is that his words/dialogue and characters stand on their own, made alive by the personalities of the actors and their choices. I’ve enjoyed actors take up this great work and turn themselves upside down into clown princes. Reeves and Winter have an affinity and humility for this uptake. And Lloyd lets them play, as he damn well should.

In the enjoyment and appreciation of their antics, the themes arrive. I’ve seen greater and lesser lights in these roles. Unfortunately, I allowed their personalities and their gravitas to distract me and take up too much space, crowding out my delight. In allowing Waiting for Godot to settle into fantastic farce, Lloyd and the exceptional cast tease out greater truths. These include the indomitably of friendship; the importance of fun; the tediousness of not being able to get out of one’s own way; the uselessness of self-victimizing complaint; the vitality and empowerment of self-deliverance, and the frustration of certain uncertainty.

Waiting for Godot runs approximately two hours five minutes with one intermission, through Jan. 4 at the Hudson Theatre. godotbroadway.com.